Abstract

Avian rotavirus NSP4 glycoproteins expressed in Escherichia coli acted as enterotoxins in suckling mice, as did mammalian rotavirus NSP4 glycoproteins, despite great differences in the amino acid sequences. The enterotoxin domain of PO-13 NSP4 exists in amino acid residues 109 to 135, a region similar to that reported in SA11 NSP4.

Group A rotaviruses (rotaviruses), members of the family Reoviridae, are recognized as the main cause of acute gastroenteritis in infants and young animals (8). Rotavirus particles have a triple-layered protein capsid which surrounds the genome of 11 segments of double-stranded RNA. The genome codes for six structural proteins and six nonstructural proteins (3). One of the nonstructural proteins, NSP4, has multiple functions in rotavirus replication and pathogenesis (1, 2, 30, 36). NSP4 serves as an intracellular receptor for immature particles and interacts with viral capsid proteins during viral morphogenesis (2, 30). NSP4s derived from mammalian rotaviruses have been shown to be enterotoxins, causing diarrhea in suckling mice (1, 11, 22, 36). Ball et al. (1) gave the following plausible hypothesis for the mechanism of diarrhea induction in suckling mice. Rotaviruses bind to and penetrate enterocytes, and they replicate in these cells. Then NSP4 expressed in these cells is released in the lumen of the intestine and interacts with surrounding enterocytes, resulting in facilitation of chloride secretion through a calcium-dependent signaling pathway, thus causing diarrhea.

Rotaviruses have also been isolated from several avian species (17-19, 29). The viruses are important agents of severe diarrhea with an increase in mortality in turkeys and pheasants (17, 18). Chickens have been found to be susceptible to rotavirus infection, but clinical signs are either mild or absent (34, 35). Previous studies have suggested that avian rotaviruses separated from mammalian rotaviruses early during evolution (13-15, 25, 26). The bovine rotavirus 993/83 was isolated in Germany from the feces of a calf suffering from diarrhea (5). The virus is more similar to avian rotaviruses than to mammalian rotaviruses in terms of genetic and antigenic properties (5, 6, 13, 25, 26). Furthermore, a pigeon rotavirus PO-13 was found to be infectious and had a level of virulence similar to that of the monkey rotavirus SA11 in a suckling ddY mouse model (21). These observations suggest that avian rotaviruses play a role as cross-species pathogens between avian and mammalian species. However, it is not known whether avian rotaviruses induce disease in mammalian animals by the same pathogenic mechanism as mammalian rotaviruses.

In a suckling mouse model, the only histopathological changes associated with PO-13 infection were vacuolation of absorptive cells in the small intestine, and there was no villous atrophy (21). Furthermore, the infected cells were few and discordant with the degenerative cells (21). These phenomena cannot be explained by classical pathological mechanisms such as malabsorption after extensive viral destruction of the intestinal epithelium, but they can be explained by the hypothesis of viral enterotoxin. However, the enterotoxigenic activity of PO-13 NSP4 in suckling mice was examined because the homology of the deduced amino acid sequences of NSP4 in PO-13 and mammalian rotaviruses was only 32 to 35% (15). On the other hand, the turkey rotavirus Ty-3 did not induce diarrhea in suckling mice (21). Zhang et al. (36) reported that the difference of virulence in suckling mice between virulent and attenuated porcine rotaviruses, OSU-v and OSU-a, is correlated to the difference of enterotoxigenic activities in suckling mice. Therefore, the aims of this study were (i) to examine whether PO-13 NSP4 had enterotoxigenic activity in suckling mice, (ii) to examine whether enterotoxigenic activities of the avian rotavirus NSP4s in suckling mice were able to explain the virulence of each strain in suckling mice, and (iii) to identify the enterotoxigenic domain of avian rotavirus NSP4s.

A pigeon rotavirus, strain PO-13 (G7, P[17], SGI), was isolated from Japanese pigeon feces collected in 1983 by using rhesus monkey kidney MA104 cells (19), and it was passaged 12 times in MA104 cells and 2 times in bovine kidney MDBK cells. Turkey rotavirus strains Ty-3 (G7, SGI) and Ty-1 (G7, SGI) and a chicken rotavirus, strain Ch-1 (G7, SGI), isolated using chicken embryo fibroblast cells and/or chick kidney cells in the United Kingdom (18), were provided by McNulty Veterinary Research Laboratories, Belfast, United Kingdom, and were passaged several times in MA104 cells in our laboratory. For this study, all of the avian rotaviruses and a simian rotavirus, SA11 (G3, P[2], SGI), were grown in MA104 cells as described previously (19). The accession numbers of the nucleotide sequences of the avian rotavirus NSP4s in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank databases were AB009627 (PO-13), AB065285 (Ty-1), AB065286 (Ty-3), and AB065287 (Ch-1).

Preparation of recombinant avian rotavirus NSP4s.

To prepare avian rotavirus NSP4-expressing plasmids, the full NSP4 genes of PO-13, Ty-3, Ty-1, and Ch-1 were generated by PCR using the recombinant plasmids containing each NSP4 gene as template. The primers used are shown in Table 1. The PCR-amplified DNAs were directly ligated with the pT7Blue T vector (Novagen), with the nucleotide sequences being confirmed and then subcloned into the pGEX-2T vector (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) using the restriction enzymes BamHI and EcoRI. Each NSP4 of the avian rotaviruses was expressed as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein in Escherichia coli and purified by the method of Smith and Johnson (28). The E. coli cell lysate that contained each NSP4 fusion protein was passed through a column of glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). After washing the column with phosphate-buffered saline and thrombin buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, and 2.5 mM CaCl2), the recombinant proteins were isolated from GST by digesting in the region between GST and NSP4 using thrombin proteinase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) in thrombin buffer and treated with benzamidine-Sepharose 6B (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) to remove the thrombin proteinase. If necessary, the proteins were concentrated by ultrafiltration using an Ultrafree-MC (10,000 nominal molecular weight limit) (Millipore). These protein concentrations were determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The expression and purification of the recombinant proteins were confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (16) and Western blotting analysis (32). The recombinant proteins were separated by electrophoresis on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and then stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (CBB). In Western blotting analyses, the recombinant proteins were reacted with a guinea pig polyclonal antiserum raised against a lysate of insect cells infected with baculovirus expressing PO-13 NSP4 (anti-PO-13 NSP4 guinea pig serum) or with anti-PO-13 VP6 monoclonal antibody P3-1 (20).

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide sequences and annealing positions of the primers used for construction of recombinant proteins in this study

| Recombinant protein | Primer | Sense | Position | Sequencea (5′-3′) | Restriction enzymeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PO-13 NSP4 and Ty-1 NSP4 | NSP4/B5 | + | 41-57 | AAG GAT CCA TGG AGA ACG CTA CCA C | BamHI |

| NSP4/E3 | − | 548-565 | AAG AAT TCG TGG GCA TGA ACC ATC A | EcoRI | |

| Ty-3 NSP4 | T3NSP4B5 | + | 41-57 | AAG GAT CCA TGG AGA ACG CTA CCA G | BamHI |

| T3NSP4E3 | − | 548-565 | AAG AAT TCA TGG ACA CGA GGC ATC A | EcoRI | |

| Ch-1 NSP4 | C1NSP4B5 | + | 41-57 | GTG GAT CCA TGG AGA ACG TCA CCA C | BamHI |

| C1NSP4E3 | − | 548-565 | TCG AAT TCG TAG ACA TGA ACC ATC A | EcoRI | |

| PONSP486-169 | NSP4-86 | + | 296-310 | TTG GAT CCA AAA CAG AAG TAG TT | BamHI |

| NSP4/E3 | − | 548-565 | AAG AAT TCG TGG GCA TGA ACC ATC A | EcoRI | |

| PONSP4109-169 | NSP4-109 | + | 365-380 | TTG GAT CCC AGG TTA AAG TTA TAG | BamHI |

| NSP4/E3 | − | 548-565 | AAG AAT TCG TGG GCA TGA ACC ATC A | EcoRI | |

| PONSP486-109 | NSP4-86 | + | 296-310 | TTG GAT CCA AAA CAG AAG TAG TT | BamHI |

| NSP4-135 | − | 431-445 | TCG AAT TCT CAC TTC AAC ATT TCA TA | EcoRI | |

| PONSP486-169Δ112-133 | |||||

| aa 86-111 | NSP4-86HB | + | 296-310 | GTA AGC TTG GAT CCA AAA CAG AAG TAG TT | HindIII, BamHI |

| NSP4-111 | − | 354-373 | ATA AGC TTA ACC TGG TTA TCA ATT T | HindIII | |

| aa 134-169 | NSP4-134 | + | 440-460 | AAA AGC TTA AGT TTA AAA AAG ATG AG | HindIII |

| NSP4/E3 | − | 548-565 | AAG AAT TCG TGG GCA TGA ACC ATC A | EcoRI |

Underlined sequences indicate restriction enzyme sites added to the NSP4 gene sequences. Sequences in bold type indicate stop codons.\

Restriction enzymes were used when nucleotides were digested at the restriction enzyme sites upon primer sequences in subcloning into expression vectors.

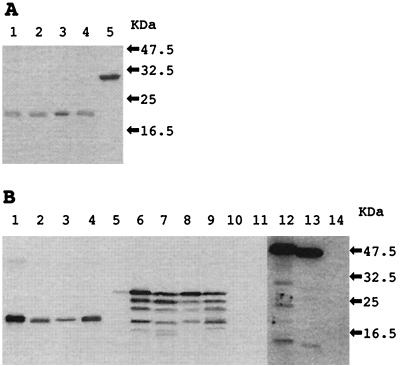

Recombinant NSP4s of the avian rotaviruses migrated as single bands with molecular masses of approximately 20 kDa (Fig. 1A). The PO-13 VP8 protein, which was prepared by similar procedures, was confirmed to be purified as a single band with a molecular mass of approximately 30 kDa (Fig. 1A). All of the recombinant NSP4s of the avian rotaviruses, but not PO-13 VP8, reacted specifically with the anti-PO-13 NSP4 guinea pig serum (Fig. 1B). The lysate of MA104 cells infected with each avian rotavirus had four major bands of NSP4 (Fig. 1B). It was predicted from those amino acid sequences that the authentic NSP4s of the avian rotaviruses had three sugar chains. The molecular masses of the recombinant NSP4 proteins agreed with those of the lowest bands of the authentic NSP4s, which were predicted to be without sugar chains (Fig. 1B). The anti-PO-13 NSP4 guinea pig serum did not react with the cell lysate infected with SA11 containing enough antigen to react with P3-1 (Fig. 1B). These observations suggested that the avian rotavirus NSP4s had different antigenic properties from SA11 NSP4. As a result, the purified NSP4s of PO-13 and Ty-1 were prepared at 400 pmol per 50 μl, while those of Ty-3 and Ch-1 were prepared at 200 pmol per 50 μl.

FIG. 1.

Expression and purification of the recombinant avian rotavirus NSP4s and PO-13 VP8: CBB staining (A) and Western blotting (B) of PO-13 NSP4, Ty-3 NSP4, Ty-1 NSP4, Ch-1 NSP4, and PO-13 VP8 from E. coli extracts. Aliquots of 20 pmol for CBB staining and 0.1 pmol for Western blotting of the purified NSP4s and VP8 were separated on an SDS-15% polyacrylamide gel. In Western blotting, the lysates of MA104 cells infected with avian rotaviruses and simian rotavirus SA11 were also analyzed. These proteins were reacted with anti-PO-13 NSP4 guinea pig serum (lanes 1 to 11) or anti-PO-13 VP6 monoclonal antibody P3-1 (lanes 12 to 14). Lane 1, PO-13 NSP4; lane 2, Ty-3 NSP4; lane 3, Ty-1 NSP4; lane 4, Ch-1 NSP4; lane 5, PO-13 VP8; lanes 6 and 12, the lysate of MA104 cells infected with PO-13; lane 7, the lysate of MA104 cells infected with Ty-3; lane 8, the lysate of MA104 cells infected with Ty-1; lane 9, the lysate of MA104 cells infected with Ch-1; lanes 10 and 13, the lysate of MA104 cells infected with SA11; lanes 11 and 14, the lysate of MA104 cells mock inoculated.

Mouse inoculation of the recombinant avian rotavirus NSP4s.

The ddY strain of closed-colony mice and the BALB/c strain of inbred mice were used in this study. Both strains were susceptible to PO-13 infection, but not Ty-3 infection (21 and data not shown). Pregnant mice of both strains were purchased from Japan SLC, Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan) and housed individually in cages. After delivery, blood samples were taken from each dam, and serum antibody was checked by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with PO-13 particles as antigens by the modified method of Burns et al. (7). All the dams checked were seronegative (titer, <200). The litters were kept with their dams throughout the course of the experiments. Inoculation of the recombinant proteins into the suckling mice was carried out using the method described by Horie et al. (11) except for the lineage and age of the mice. Briefly, litters of 4- to 5-day-old suckling mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 50 μl of various concentrations of the purified proteins. Inoculated mice were observed for diarrhea every 2 h for the first 10 h and at 24 h postinoculation by gentle abdominal palpation. The state of stool was classified into three categories as described previously (21): watery stool, loose yellow stool, and ordinary stool. Only watery stool was considered as diarrhea. Based on the results obtained from a series of dilutions of the recombinant proteins, a 50% diarrhea-inducing dose (DD50) was calculated by the method of Reed and Müench (24).

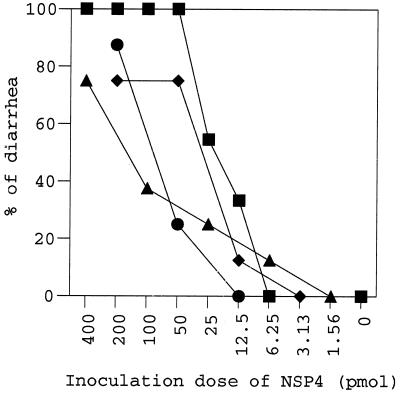

The ddY mice inoculated intraperitoneally with PO-13 NSP4 had diarrhea in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2), and the DD50 value for PO-13 NSP4 was 21 pmol (Table 2). None of the ddY mice inoculated with 1,700 pmol of PO-13 VP8 had any symptoms (Table 2). The appearance of the diarrhea induced by PO-13 NSP4 was watery and yellow, resembling that induced by oral administration of PO-13 (21). The onset of diarrhea caused by this protein occurred from 2 to 6 h postinoculation, and the duration of diarrhea was less than 8 h. Similarly, intraperitoneal inoculation of PO-13 NSP4, but not that of PO-13 VP8, induced diarrhea in suckling BALB/c mice. The pathogenicity of PO-13 NSP4 for suckling mice was similar to that previously reported for mammalian rotavirus NSP4s in terms of onset, duration, symptoms, and diarrhea-inducing dose (1, 11, 36), suggesting that the PO-13 NSP4 has enterotoxigenic activity in suckling mice similar to that of NSP4s of the mammalian rotaviruses. The results also suggest that PO-13 NSP4 contributes to the pathogenicity of PO-13 for suckling mice. Only intraperitoneal inoculation of PO-13 NSP4, but not oral inoculation, induced diarrhea in suckling mice. NSP4 might be inactivated in gastrointestinal tracts of suckling mice, but NSP4 inoculated intraperitoneally might reach enterocytes via systemic circulation instead of directly reacting with enterocytes.

FIG. 2.

Percentages of suckling ddY mice with diarrhea after inoculation with various doses of the purified NSP4s of avian rotaviruses. The mice scored as positive were observed to have diarrhea once and more during the observation times. Each dose group consisted of more than eight mice. ▪, PO-13 NSP4; •, Ty-3 NSP4; ▴, Ty-1 NSP4; ♦, Ch-1 NSP4.

TABLE 2.

DD50 values in suckling mice of purified NSP4s and VP8 from avian rotaviruses

| Inoculum | DD50 (pmol)a |

|---|---|

| PO-13 NSP4 | 21 |

| Ty-3 NSP4 | 138 |

| Ty-1 NSP4 | 108 |

| Ch-1 NSP4 | 41 |

| PO-13 VP8 | >1,700 |

The DD50 values of NSP4 and VP8 intraperitoneal inoculation were determined in 4- or 5-day-old ddY mice.

Previously, we reported that oral inoculation of PO-13, but not of Ty-3, induced diarrhea in suckling ddY mice (21). The virulences of two other avian rotaviruses, Ty-1 and Ch-1, were determined in 3- or 4-day-old ddY mice as described previously (21). None of the mice inoculated orally with Ty-1 or Ch-1 had diarrhea, and the DD50 values of Ty-1 and Ch-1 were >1.5 × 108 and >3.6 × 106 focus-forming units, respectively. Therefore, we examined whether the difference between the virulent strain PO-13 and avirulent strains Ty-3, Ty-1, and Ch-1 in suckling mice correlated with the differences in enterotoxigenic activity of these NSP4s. The amino acid sequences of NSP4s from PO-13, Ty-3, and Ty-1 are conserved, while Ch-1 NSP4 is different from the other avian rotavirus NSP4s. The NSP4 sequences of the avian rotaviruses are 6 to 7 amino acids (aa) shorter than those of mammalian strains and have considerably lower identities (31 to 37%) with them. The purified NSP4s of these strains expressed in E. coli also induced diarrhea in suckling ddY mice via intraperitoneal inoculation in a dose-dependent manner, indicating that these NSP4s had enterotoxigenic activity (Fig. 2). The DD50 values for Ty-3, Ty-1, and Ch-1 NSP4 were 138, 108, and 41 pmol, respectively (Table 2). Although these values were 2.0- to 6.6-fold higher than that of PO-13 NSP4, these results failed to explain the extreme differences in pathogenicities in suckling mice between PO-13 and the other avian rotaviruses. Comparisons of the NSP4 sequences from pairs of virulent and attenuated rotaviruses have been performed to define the potential role of NSP4 in rotaviral diarrhea mechanisms (23, 33, 36). Zhang et al. (36) reported that amino acid substitutions in NSP4 of virulent and attenuated OSU porcine rotavirus strains are strongly related to changes in virulence of both strains. However, Ward et al. (33) and Oka et al. (23) failed to find any consistent and significant changes in NSP4 sequences of symptomatic versus asymptomatic isolates. The differences in pathogenicities of the latter cases and our cases appeared to be associated with genes other than those encoding NSP4s. In fact, it was reported that PO-13, but not Ty-3, could replicate in suckling mice (21), and the results of inoculation of a series of reassortants derived from PO-13 and Ty-3 in suckling mice indicated that the determinants of difference between virulences of both strains were VP4 and VP7 (Y. Mori et al., unpublished data). The susceptibility of suckling mice to Ty-3 NSP4 is much higher than that to infection of Ty-3. Ty-3 probably failed to infect intestinal cells of suckling mice prior to the production and release of its NSP4 (21). Similarly, the strong susceptibility of suckling mice to NSP4s may contribute to the pathogenicity of heterologous rotaviruses such as PO-13, which can only replicate to a limited extent (21).

Enterotoxin domain of avian rotavirus NSP4s.

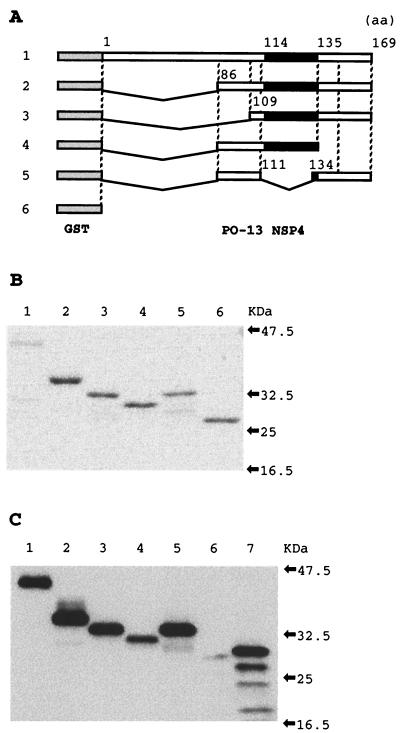

Ball et al. (1) determined that the enterotoxin domain on the SA11 NSP4 existed in aa 114 to 135. This region is conserved in avian and mammalian rotavirus NSP4s, with homologies from 50 to 59%. In the avian rotavirus NSP4s, aa 109 to 135 are completely identical except for a single amino acid substitution between Ch-1 and the others. These findings on amino acid sequences of NSP4s led us to speculate that the enterotoxin domain of the avian rotavirus NSP4s existed in this region. To determine this, we prepared a series of truncated NSP4s of PO-13. Construction of expression vectors was performed by cloning PCR products, which were generated using the primers indicated in Table 1, into the pGEX-2T plasmids. To construct the region corresponding to aa 86 to 169 of PO-13 NSP4 without aa 112 to 133 (Fig. 3A), two regions corresponding to aa 86 to 111 and aa 134 to 169 were separately generated by PCR. The PCR-amplified DNA of aa 134 to 169 was treated with the restriction enzymes HindIII and EcoRI and then cloned into the pUC19 vector (Takara) treated with HindIII and EcoRI. The PCR-amplified DNA of aa 86 to 111 was treated with HindIII and cloned into the pUC19 vector containing the DNA of aa 134 to 169, which was treated with HindIII. The combined DNA of aa 86 to 111 and aa 134 to 169 was subcloned into the pGEX-2T vector. To deal easily with truncated PO-13 NSP4s, these proteins expressed in E. coli were purified without removing GST, by elusion from a column of glutathione-Sepharose 4B using 10 mM reduced glutathione (Takara) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0).

FIG. 3.

Expression and purification of GST-full-length and truncated PO-13 NSP4 fusion proteins and GST. (A) Schematic representation of GST-PO-13 NSP4, four GST-truncated PO-13 NSP4s, and GST. Shaded boxes represent GST and black boxes represent the region corresponding to the enterotoxin domain (aa 114 to 135) of the SA11 NSP4 (1). (B and C) CBB staining (B) and Western blotting (C) of GST-PO-13 NSP4, four GST-truncated PO-13 NSP4s, and GST from E. coli extracts. For CBB staining, aliquots of 10 pmol of the purified GST-PO-13 NSP4 and 50 pmol of the purified GST-truncated PO-13 NSP4s and the purified GST were separated on an SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel. For Western blotting, 0.5 pmol of these proteins was reacted with anti-PO-13 NSP4 guinea pig serum. Lane 1, GST-PO-13 NSP4; lane 2, PONSP486-169; lane 3, PONSP4109-169; lane 4, PONSP486-135; lane 5, PONSP486-169Δ112-133; lane 6, GST.

We prepared a full-length PO-13 NSP4 (GST-PO-13 NSP4) and four truncated PO-13 NSP4s, aa 86 to 169 (PONSP486-169), aa 109 to 169 (PONSP4109-169), aa 86 to 135 (PONSP486-135), and aa 86 to 169 truncated in aa 112 to 133 (PONSP486-169Δ112-133) of PO-13 NSP4 as GST fusion proteins in E. coli (Fig. 3). GST-PO-13 NSP4, PONSP486-169, PONSP4109-169, PONSP486-135, PONSP486-169Δ112-133, and GST migrated with molecular masses of 41, 36, 33, 31, 33, and 26 kDa, respectively, and their purities were confirmed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3B). All of GST-PO-13 NSP4 and four truncated PO-13 NSP4s, but not GST, reacted specifically with anti-PO-13 NSP4 guinea pig serum (Fig. 3C). The purified GST-PO-13 NSP4 was prepared at 0.1 nmol per 50 μl, while the purified GST-truncated PO-13 NSP4 fusion proteins and GST were prepared at 2 nmol per 50 μl, since it was reported that activities of truncated NSP4s were weaker than those of full-length of NSP4s (1, 11).

Although the enterotoxigenic activity of PO-13 NSP4 with GST was slightly weaker than that of PO-13 NSP4 without GST, it was confirmed that 0.1 nmol of GST-PO-13 NSP4 induced diarrhea in suckling ddY mice (Table 3). On the other hand, none of the 10 mice given 2 nmol of GST had diarrhea (Table 3), with a statistically significant difference from GST-PO-13 NSP4 by Fisher's direct test (P < 0.01). To determine the enterotoxin domain on PO-13 NSP4, suckling ddY mice were intraperitoneally inoculated with 2 nmol of the GST-truncated PO-13 NSP4 fusion proteins. PONSP486-169, PONSP4109-169, and PONSP486-135 induced diarrhea in 60% (6 of 10), 80% (8 of 10), and 50% (5 of 10) of the mice, respectively (Table 2). Although the severity and duration of diarrhea induced by the proteins was slightly weaker than with full-length PO-13 NSP4 (data not shown), these results were significantly different by Fisher's direct test (P < 0.01) from those obtained by giving GST. These proteins overlapped each other in aa 109 to 135. On the other hand, none of the mice inoculated with PONSP486-169Δ112-133, in which aa 112 to 133 were deleted from PONSP486-169, had diarrhea (Table 3). These results indicated that aa 109 to 135 of PO-13 NSP4, a similar region to that reported in SA11 NSP4 (1), had enterotoxigenic activity in suckling mice. Furthermore, the fact that the amino acid sequences in this region are almost identical in the avian rotaviruses suggests that this region of the NSP4s also acts as the enterotoxin domain in suckling mice. The work with porcine viruses showed that regions from aa 131 to 140 of NSP4s can be associated with changes in virulence (36). There are two and three amino acid changes in Ty-3 and Ch-1 NSP4s, respectively, compared to PO-13 and Ty-1 NSP4s and, in addition, Ch-1 has a gap at aa 138 of NSP4. These amino acid substitutions might be associated with the differences in the DD50 values of the avian rotavirus NSP4s determined in this study. However, the differences in the DD50 values of PO-13 and Ty-1 NSP4, which are completely identical in the enterotoxin domain and the virulence-associated region, might have resulted from amino acid substitutions in other regions of the NSP4s or from the degree of the purities or inactivations of NSP4s throughout the course of the preparation.

TABLE 3.

Diarrhea induced by intraperitoneal administration of GST-PO-13 NSP4 fusion proteins in suckling ddY mice

| Protein | Dose (nmol) | Diarrhea inductiona |

|---|---|---|

| GST-PO-13 NSP4 | 0.1 | 6/10 |

| PONSP486-169 | 2.0 | 8/10 |

| PONSP4109-169 | 2.0 | 5/10 |

| PONSP486-135 | 2.0 | 6/10 |

| PONSP486-169Δ112-133 | 2.0 | 0/10 |

| GST | 2.0 | 0/10 |

All ddY mice were intraperitoneally inoculated with recombinant proteins at 4 or 5 days of age. Data are expressed as number of positive mice per number of tested mice. The mice scored as positive were observed to have diarrhea once or more often during the observation time.

The previous reports that many NSP4s of mammalian rotaviruses belonging to various genotypes had enterotoxigenic activity in suckling mice (1, 11, 22, 36) and the present results that NSP4s of the avian rotaviruses, which differ extremely from NSP4s of mammalian rotaviruses in amino acid sequences, had also enterotoxigenic activity in suckling mice suggest that this activity is important in nature and is generally conserved in NSP4s of rotaviruses. Sasaki et al. (27) reported that group C rotavirus NSP4 also had enterotoxigenic activity in suckling mice despite an extreme difference in amino acid sequences from group A rotavirus NSP4s. It was suggested that structural features of NSP4s were important for these enterotoxigenic activities rather than the identities of these amino acid sequences, because group A and C rotavirus NSP4s were conserved in these hydrophobicity profiles and coiled-coil structures in spite of differences in amino acid sequences (12). Similarly, avian rotavirus NSP4s had structural features similar to those of mammalian rotavirus NSP4s in the enterotoxin domain (Y. Mori, M. A. Borgan, N. Ito, M. Sugiyama, and N. Minamoto, submitted for publication). The importance of structural features for enterotoxigenic activity of NSP4s was also suggested by the fact that a larger inoculum of truncated NSP4s than of full-length NSP4s was necessary to induce diarrhea in suckling mice (1, 11).

Many kinds of NSP4s of rotaviruses isolated from various animal species (monkeys, pigs, mice, pigeons, turkeys, and chickens) have enterotoxigenic activities in suckling mice (1, 11, 22, 36), suggesting that NSP4s act as enterotoxins in natural hosts. Although only suckling mice were previously confirmed to be susceptible to NSP4s, Halaihel et al. (10) reported that a synthetic peptide corresponding to aa 114 to 135 of SA11 NSP4 reacted with the NA+-d-glucose symporter of vesicles derived from rabbit intestinal brush border membrane, and Guerin-Danan et al. (9) raised the possibility that SA11 NSP4 acts as an enterotoxin in rats. Although further study of avian rotavirus NSP4s inoculated in chicks is necessary, avian rotavirus NSP4s might have enterotoxigenic activity in avian species, because avian rotaviruses showed pathological features in avian species as did mammalian rotaviruses in mammalian species (35).

Acknowledgments

We thank M. S. McNulty for providing the turkey rotaviruses Ty-1 and Ty-3 and the chicken rotavirus Ch-1 and O. Nakagomi for providing the simian rotavirus SA-11.

This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (no. 13460141).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ball, J. M., P. Tian, C. Zeng, A. P. Morris, and M. K. Estes. 1996. Age-dependent diarrhea induced by a rotaviral nonstructural glycoprotein. Science 272:101-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergmann, C. C., D. Maass, M. S. Poruchynsky, P. H. Atkinson, and A. R. Bellamy. 1989. Topology of the non-structural rotavirus receptor glycoprotein NS28 in the rough endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 8:1695-1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Both, G. W., A. R. Bellamy, and D. B. Mitchell. 1994. Rotavirus protein structure and function. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 185:67-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman, G. D., I. M. Nodelman, O. Levy, S. L. Lin, P. Tian, T. J. Zamb, S. A. Udem, B. Venkataraghavan, and C. E. Schutt. 2000. Crystal structure of the oligomerization domain of NSP4 from rotavirus reveals a core metal-binding site. J. Mol. Biol. 304:861-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brüssow, H., O. Nakagomi, G. Gerna, and W. Eichhorn. 1992. Isolation of an avianlike group A rotavirus from a calf with diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:67-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brüssow, H., O. Nakagomi, N. Minamoto, and W. Eichhorn. 1992. Rotavirus 993/83, isolated from calf faeces, closely resembles an avian rotavirus. J. Gen. Virol. 73:1873-1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns, J. W., A. A. Krishnaney, P. T. Vo, R. V. Rouse, L. J. Anderson, and H. B. Greenberg. 1995. Analyses of homologous rotavirus infection in the mouse model. Virology 207:143-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estes, M. K., and J. Cohen. 1989. Rotavirus gene structure and function. Microbiol. Rev. 53:410-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerin-Danan, C., J. C. Meslin, F. Lambre, A. Charpilienne, M. Serezat, C. Bouley, J. Cohen, and C. Andrieux. 1998. Development of a heterologous model in germfree suckling rats for studies of rotavirus diarrhea. J. Virol. 72:9298-9302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halaihel, N., V. Lievin, J. M. Ball, M. K. Estes, F. Alvarado, and M. Vasseur. 2000. Direct inhibitory effect of rotavirus NSP4(114-135) peptide on the Na+-d-glucose symporter of rabbit intestinal brush border membrane. J. Virol. 74:9464-9470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horie, Y., O. Nakagomi, Y. Koshimura, T. Nakagomi, Y. Suzuki, T. Oka, S. Sasaki, Y. Matsuda, and S. Watanabe. 1999. Diarrhea induction by rotavirus NSP4 in the homologous mouse model system. Virology 262:398-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horie, Y., T. Nakagomi, M. Oseto, O. Masamune, and O. Nakagomi. 1997. Conserved structural features of nonstructural glycoprotein NSP4 between group A and group C rotaviruses. Arch. Virol. 142:1865-1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito, H., N. Minamoto, S. Hiraga, and M. Sugiyama. 1997. Sequence analysis of the VP6 gene in group A turkey and chicken rotaviruses. Virus Res. 47:79-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito, H., N. Minamoto, I. Sasaki, H. Goto, M. Sugiyama, T. Kinjo, and S. Sugita. 1995. Sequence analysis of cDNA for the VP6 protein of group A avian rotavirus: a comparison with group A mammalian rotaviruses. Arch. Virol. 140:605-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito, H., M. Sugiyama, K. Masubuchi, Y. Mori, and N. Minamoto. 2001. Complete nucleotide sequence of a group A avian rotavirus genome and a comparison with its counterparts of mammalian rotavirus. Virus Res. 75:123-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Legrottaglie, R., V. Rizzi, and P. Agrimi. 1997. Isolation and identification of avian rotavirus from pheasant chicks with signs of clinical enteritis. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:205-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McNulty, M. S., G. M. Allan, D. Todd, J. B. McFerran, E. R. McKillop, D. S. Collins, and R. M. McCracken. 1980. Isolation of rotaviruses from turkeys and chickens: demonstration of distinct serotypes and RNA electropherotypes. Avian Pathol. 9:363-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minamoto, N., K. Oki, M. Tomita, T. Kinjo, and Y. Suzuki. 1988. Isolation and characterization of rotavirus from feral pigeon in mammalian cell cultures. Epidemiol. Infect. 100:481-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minamoto, N., O. Sugimoto, M. Yokota, M. Tomita, H. Goto, M. Sugiyama, and T. Kinjo. 1993. Antigenic analysis of avian rotavirus VP6 using monoclonal antibodies. Arch. Virol. 131:293-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mori, Y., M. Sugiyama, M. Takayama, Y. Atoji, T. Masegi, and N. Minamoto. 2001. Avian-to-mammal transmission of an avian rotavirus: analysis of its pathogenicity in a heterologous mouse model. Virology 288:63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris, A. P., J. K. Scott, J. M. Ball, C. Q. Zeng, W. K. O'Neal, and M. K. Estes. 1999. NSP4 elicits age-dependent diarrhea and Ca2+ mediated I− influx into intestinal crypts of CF mice. Am. J. Physiol. 277:431-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oka, T., T. Nakagomi, and O. Nakagomi. 2001. A lack of consistent amino acid substitutions in NSP4 between rotaviruses derived from diarrheal and asymptomatically-infected kittens. Microbiol. Immunol. 45:173-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reed, L. J., and H. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rohwedder, A., H. Hotop, N. Minamoto, H. Ito, O. Nakagomi, and H. Brüssow. 1997. Bovine rotavirus 993/83 shows a third subtype of avian VP7 protein. Virus Genes 14:147-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohwedder, A., K. I. Schutz, N. Minamoto, and H. Brüssow. 1995. Sequence analysis of pigeon, turkey, and chicken rotavirus VP8* identifies rotavirus 993/83, isolated from calf feces, as a pigeon rotavirus. Virology 210:231-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sasaki, S., Y. Horie, T. Nakagomi, M. Oseto, and O. Nakagomi. 2001. Group C rotavirus NSP4 induces diarrhea in neonatal mice. Arch. Virol. 146:801-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith, D. B., and K. S. Johnson. 1988. Single-step purification of polypeptides expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with glutathione S-transferase. Gene 67:31-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takehara, K., H. Kiuchi, M. Kuwahara, F. Yanagisawa, M. Mizukami, H. Matsuda, and M. Yoshimura. 1991. Identification and characterization of a plaque forming avian rotavirus isolated from a wild bird in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 53:479-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor, J. A., J. C. Meyer, M. A. Legge, J. A. O'Brien, J. E. Street, V. J. Lord, C. C. Bergmann, and A. R. Bellamy. 1992. Transient expression and mutational analysis of the rotavirus intracellular receptor: the C-terminal methionine residue is essential for ligand binding. J. Virol. 66:3566-3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor, J. A., J. A. O'Brien, and M. Yeager. 1996. The cytoplasmic tail of NSP4, the endoplasmic reticulum-localized non-structural glycoprotein of rotavirus, contains distinct virus binding and coiled coil domains. EMBO J. 15:4469-4476. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ward, R. L., B. B. Mason, D. I. Bernstein, D. S. Sander, V. E. Smith, G. A. Zandle, and R. S. Rappaport. 1997. Attenuation of a human rotavirus vaccine candidate did not correlate with mutations in the NSP4 protein gene. J. Virol. 71:6267-6270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yason, C. V., and K. A. Schat. 1987. Pathogenesis of rotavirus infection in various age groups of chickens and turkeys: clinical signs and virology. Am. J. Vet. Res. 48:977-983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yason, C. V., B. A. Summers, and K. A. Schat. 1987. Pathogenesis of rotavirus infection in various age groups of chickens and turkeys: pathology. Am. J. Vet. Res. 48:927-938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang, M., C. Q. Zeng, Y. Dong, J. M. Ball, L. J. Saif, A. P. Morris, and M. K. Estes. 1998. Mutations in rotavirus nonstructural glycoprotein NSP4 are associated with altered virus virulence. J. Virol. 72:3666-3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]