Abstract

Purpose: To evaluate the results of a graded treatment approach in a cohort of eyes with macular complications of immune recovery uveitis.

Methods: A cohort of 18 eyes of 13 patients representing all eyes with these complications at the University of California, San Diego AIDS Ocular Treatment Unit was studied. Eyes were classified into three groups and treated according to a graded protocol.

Results: Eyes with mild disease (macular edema and vision of 20/30 or better) were observed. These six eyes maintained good vision with only one dropping to 20/40. In eyes with worse macular edema and vision of 20/30 or worse (10 eyes of 9 patients), repository sub-Tenon steroid injections were used repeatedly. There were no complications of steroid use but visual improvement occurred in only 40% of eyes. Macular edema persisted. In eyes with structural macular changes, such as epiretinal membrane, vitrectomy resulted in vision improvement in three of four eyes. The cystoid macular edema persisted despite surgery.

Conclusion: Mild cases of immune recovery uveitis and macular edema may be observed. In eyes with reduction of vision due to cystoid macular edema, there was only a modest treatment effect using repository corticosteroids. Eyes with immune recovery uveitis that develop epiretinal membrane undergo some visual improvement after removal of the membrane. The macular edema of immune recovery uveitis is resistant to corticosteroid treatment.

Keywords: cytomegalovirus retinitis, epiretinal membrane, human immunodeficiency virus, macular edema, uveitis

Cytomegalovirus retinitis (CMV) is the most common cause of blindness in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).1 Typically, CMV is a late opportunistic infection and generally occurs after the CD4 T lymphocyte count has fallen below 50 cells/mm3 and very rarely at CD4 counts above 100/mm3.2 CMV in patients with AIDS is typically characterized by progressive necrotizing retinitis associated with mild or no intraocular inflammation.3

Immune recovery uveitis (IRU) is a recently described syndrome of predominantly vitreous inflammatory reaction in patients with AIDS and inactive CMV retinitis. The syndrome is associated with increased immunocompetence as a result of highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) including protease inhibitors.4,5 The clinical picture of IRU is still evolving. We previously reported that IRU is a persistent condition and is characterized clinically by a decrease of vision, floaters, vitritis, papillitis, and macular changes including macular edema and epiretinal membrane (ERM).6 However, Zegans et al reported that IRU is a transient vitritis with improvement in visual acuity (VA) within 6 weeks of initial diagnosis regardless of treatment.5 Canzano et al reported 2 cases of IRU with cystoid macular edema (CME), which were persistent and resistant to treatment. The authors attributed the edema to the presence of vitreomacular traction syndrome in these two patients, which was confirmed by ultrasonography.7

Previously, oral steroids have been reported to be a risk factor for CMV retinitis in HIV-positive patients with a low CD4 lymphocyte count.8 However, successful steroid treatment for IRU has been reported without complications.6 Henderson and Mitchell reported successful treatment of nine eyes of seven patients of IRU with orbital floor steroids. Four of these nine eyes had CME, which showed improvement or disappearance after this treatment. No complications were reported.9

The goal of our study was to evaluate the results of treatment in eyes with macular complications associated with IRU using a graded treatment approach. We chose to study macular complications because they can be documented by fundus photography and fluorescein angiography and they are associated with structural retinal changes and visual symptoms.

Patients and Methods

To identify all cases of macular complications between November 1996 and January 2000, we studied all patients who were diagnosed with symptomatic IRU at the AIDS Ocular Research Unit of the University of California, San Diego. A total of 13 patients (18 eyes) with macular complications were found. The current study is a longitudinal cohort study of 18 eyes in 13 patients with a median of 83.1 weeks follow-up. Nine of these eyes were reported in a previous study with shorter follow-up.10 All patients signed consent forms for data gathering and analysis.

Full ophthalmologic examinations were performed on all patients at each visit. Best-corrected VA was assessed with the Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study VA chart. The VA of patients with cataract was assessed by potential VA meter. All patients underwent standardized slit-lamp examination with grading of anterior chamber cells and flare and bilateral indirect ophthalmoscopy at each visit. The macula was examined using slit lamp and +78 D lens. The vitritis was evaluated according to the grading system proposed by Nussenblatt et al.11 The results of the examination were confirmed by fundus drawing and wide-angle (50–60 degree) fundus photographs at each visit.

Fluorescein angiography was performed on all patients and was repeated when clinically indicated for follow-up. The extent of CME was measured in disk diameters using the method described by Weizz et al.12 The levels of CD4 T lymphocyte and human immunodeficiency virus mRNA were monitored every 2 to 3 months. All patients' data were recorded prospectively in an electronic database at each visit. All patient medications were reviewed to exclude from the cohort patients who had received rifabutin or cidofovir within 2 months of the onset of the inflammation. Patients with CMV affecting the macula were also excluded.

The eyes of patients with IRU and macular changes were prospectively classified into three groups based on clinical presentation and treated using a graded approach as follows.

Group 1

Group 1 consisted of eyes with CME and VA better than 20/30. This group included six eyes of six patients. These eyes were observed without treatment.

Group 2

Group 2 included eyes with CME or macular surface changes and vision equal to or below 20/30. This group included 10 eyes of 9 patients. All these eyes were treated by a series of posterior sub-Tenon injections of repository corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 80 mg). The number of injections ranged from 3 to 10.

Group 3

Group 3 eyes had developed ERM that distorted the macula. This group included four eyes of three patients. All patients who underwent surgery first had treatment with repository steroids (Depo-Medrol 80) sub-Tenon if there was macular edema present. This group was treated by trans pars plana vitrectomy (TPPV) and membrane peeling.

We performed our analysis per eye as some eyes fell into more than one clinical classification.

Results

This study included 18 eyes of 13 patients, all of which had IRU-associated macular complications. Complications included CME and ERM formation. Eleven patients (84.6%) were men and 2 (15.4%) were women. The average follow-up was 83.1 weeks. Their ages ranged from 32 to 55 years (median = 39.2 years). The patients were classified and treated according to three groups.

Group 1 (Mild Cases)

This group included six eyes of six patients. All of these patients had VA better than 20/30 at the onset of IRU. No treatment was given to these patients and they were followed for a period ranging between 40 and 144 weeks, with an average of 82.6 weeks of follow-up. At the end of the follow-up period, VA in two patients improved to 20/20. Three patients maintained the same level of VA (20/20) without deterioration. Only one patient had a drop in his VA by two lines (20/25–20/40). As regards vitritis at the onset of the inflammation, five patients had vitritis grade 1 and one patient had vitritis grade 3. Four of the five patients with vitritis grade 1 showed complete disappearance of vitritis at the end of the follow up-period; in one patient, the vitritis persisted but without increase. The patient with vitritis grade 3 improved to grade 1. Therefore, 5 out of 6 (83.3%) patients showed improvement in their vitreous inflammation. All of these patients had CME at the onset of IRU ranging between 0.5 and 4 DD (mean = 1.4 DD) in size. Two out of 6 (33.3%) of the patients showed complete disappearance of the edema at the end of the follow-up period. One showed improvement and 3 (50%) showed persistent CME without increase. Only one eye developed mild ERM in the form of parafoveal surface changes (Table 1). Four out of 6 (66.6%) patients in this group had a history of cidofovir treatment. In one patient in this group, the CMV retinitis had regressed due to antiretroviral therapy–associated immune recovery without anti-CMV treatment. The other five patients received anti-CMV treatment and in two of them the treatment continued after the onset of IRU.

Table 1.

Ocular Data of Group 1 (IRU Associated With Macular Complications and VA >20/30)

| Variable | Eye 1 | Eye 2 | Eye 3 | Eye 4 | Eye 5 | Eye 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 33 | 44 | 54 | 35 | 48 | 38 |

| Sex | M | M | M | M | F | F |

| Eye | R | L | R | R | R | R |

| Follow-up period, wk | 40 | 52 | 79 | 93 | 144 | 88 |

| VA | ||||||

| Onset | 20/25 | 20/25 | 20/25 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 |

| End | 20/40 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 |

| Macular edema | ||||||

| Onset | 4 DD | 0.5 DD | 1 DD | 1 DD | 0.5 DD | 1.5 DD |

| End | 4 DD | 0 DD | 1 DD | 0.5 DD | 0 DD | 1.5 DD |

| Vitritis | ||||||

| Onset | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| End | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| ERM | Mild ERM | |||||

| HIV RNA | ||||||

| Onset of IRU | 624,000 | 660,000 | 1,448 | 500 | 0 | |

| Stop of treatment | 624,000 | 213,000 | 1,448 | 0 | 3,290 | |

| CD4 count | ||||||

| Onset of IRU | 85 | 142 | 147 | 340 | 271 | |

| Stop of treatment | 55 | 113 | 147 | 160 | 44 | |

| CMV treatment period, wk | 54 | 51 | 104 | 16 | Auto regressed | 21 |

| CMV discontinued up to IRU onset, wk | −8 | 27 | −1 | 55.8 | 46 | |

| Cidofovir history* | + | + | − | + | − | + |

− Indicates that anti-CMV treatment continued after the onset of IRU.

Patient 1 stopped intravitreal cidofovir 12 weeks before the onset of IRU but he continued on oral ganciclovir for 8 weeks after the onset of IRU.

IRU = immune recovery uveitis; VA = visual acuity; ERM = epiretinal membrane; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; CMV = cytomegalovirus.

Group 2 (Vision-Threatening CME)

This group included 10 eyes of 9 patients. All of these eyes had a VA equal to or worse than 20/30 associated with CME (mean = 1.9 DD). These patients were treated by a series of posterior sub-Tenon injections of methylprednisolone 80 mg ranging from 3 to 10 injections. None of these patients developed reactivation of CMV, glaucoma, or any other complications related to steroid injections. VA improved in only four eyes (40%): one eye improved by one line, two eyes improved by two lines, and one eye improved by eight lines from hand motions to 20/40. The improvement in vision in the last case was due to marked improvement in vitreous inflammation from grade 4 to grade 1. Two eyes maintained the same VA as before treatment without improvement. Four eyes (40%) showed VA deterioration during treatment: three dropped by one line and one dropped by four lines (Figures 1-3). As regards vitritis, six eyes (60%) showed improvement after treatment with complete disappearance of vitritis in two of them. Two eyes maintained the same level of vitritis as before treatment. Two eyes (20%) showed increase in vitritis despite treatment. CME was present in all 10 eyes ranging between 0.5 DD and 4 DD (median = 1.95 DD). Two eyes (20%) showed improvement in CME with treatment but without disappearance. The edema was persistent in six eyes (60%). In two eyes (20%), the edema worsened despite treatment. In addition, 5 out of the 10 eyes developed ERM during the period of follow-up. In two of these five eyes, the membrane was dense enough to indicate vitrectomy (Table 2). Six out of 10 (60%) patients in this group had a history of cidofovir treatment. In one patient of this group, the CMV retinitis was regressed without anti-CMV treatment. In the other eight patients in this group, the anti-CMV treatment was discontinued before the onset of IRU.

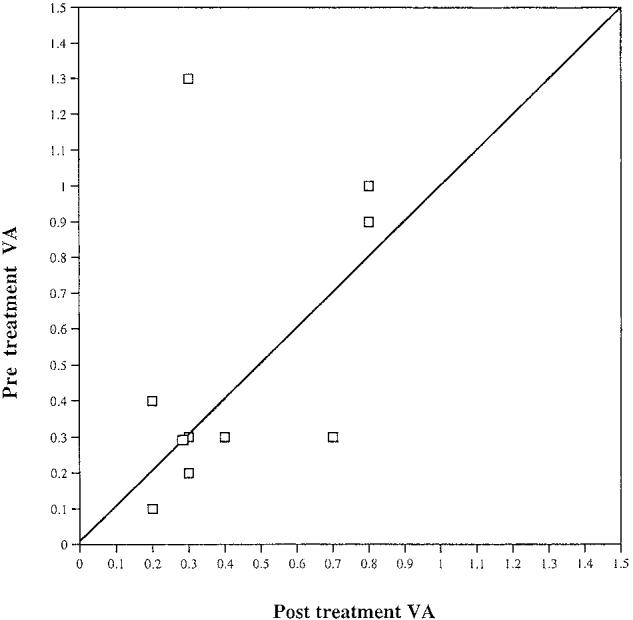

Fig. 1.

Correlation between pre- and post-treatment visual acuity (VA) in Group 2 patients treated with posterior sub-Tenon injection of corticosteroids. This suggests that there is no clear evidence of a therapeutic response.

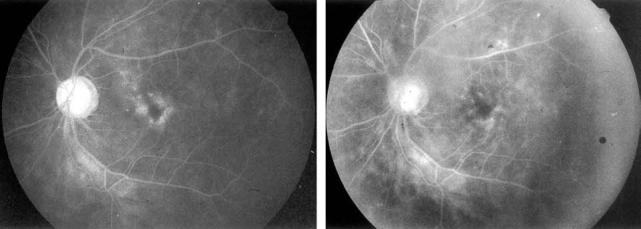

Fig. 3.

A, Late phase fluorescein angiogram of a patient with immune recovery uveitis and cystoid macular edema before repository corticosteroids. His best-corrected Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study visual acuity was 20/25 and he had symptoms of vision decline and floaters. B, Late phase fluorescein angiogram of the same patient 6 months later after four injections of repository corticosteroids. The cystoid macular edema improved but the visual acuity did not.

Table 2.

Ocular Data of Group 2 (IRU Associated With Macular Complications and VA ≤20/30)

| Variables | Eye 1 | Eye 2 | Eye 3 | Eye 4 | Eye 5 | Eye 6 | Eye 7 | Eye 8 | Eye 9 | Eye 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 32 | 41 | 54 | 30 | 55 | 55 | 44 | 31 | 48 | 36 |

| Sex | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | F | M |

| Eye | L | R | L | R | R | L | L | L | L | R |

| Follow-up period, wk | 58 | 121 | 79 | 66 | 118 | 118 | 40 | 90 | 116 | 83 |

| VA | ||||||||||

| Onset | 20/40 | 20/50 | 20/160 | HM | 20/40 | 20/25 | 20/200 | 20/40 | 20/40 | 20/32 |

| End | 20/40 | 20/32 | 20/125 | 20/40 | 20/50 | 20/32 | 20/125 | 20/40 | 20/100 | 20/40 |

| Macular edema | ||||||||||

| Onset | 3 DD | 1 DD | 1.5 DD | 3.5 DD | 0.5 DD | 1 DD | 4 DD | 2 DD | 1.5 DD | 1.5 DD |

| End | 3 DD | 1 DD | 1.5 DD | 3.5 DD | 1.5 DD | 0.75 DD | 2 DD | 2 DD | 1.5 DD | 3.5 DD |

| Vitritis | ||||||||||

| Onset | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| End | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| ERM | ERM | ERM | Sheen | ERM | Dense ERM | Dense ERM | ||||

| No. of Depo-Medrol injections | 3 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 10 |

| HIV RNA | ||||||||||

| Onset of IRU | 5,450 | 1,715 | 750,000 | 7,070 | 399 | 399 | 0 | 399 | 399 | 194,000 |

| Stop of treatment | 3,460 | 399 | 1,448 | 399 | 399 | 399 | 0 | NA | 399 | 2,600 |

| CD4 count | ||||||||||

| Onset of IRU | 236 | 158 | 164 | 10 | 120 | 120 | 339 | 186 | 294 | 472 |

| Stop of treatment | 162 | 184 | 147 | 441 | 120 | 120 | 139 | 107 | 404 | 317 |

| CMV treatment period, wk | 52 | 53 | 104 | 214 | 48 | 48 | 93 | Auto regressed | 45 | 102 |

| CMV discontinued up to IRU onset, wk | 14 | 11 | 29 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 69 | 102 | 16 | |

| Cidofovir history | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + |

IRU = immune recovery uveitis; VA = visual acuity; HM = hand motions; ERM = epiretinal membranes; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; CMV = cytomegalovirus.

Group 3 (ERM and Macular Edema)

This group included four eyes of three patients with clinically significant dense ERM. Two of these eyes were previously treated by a series of repository corticosteroid injections without improvement. TPPV and membrane peeling was performed in all four eyes. The ERM was removed without complications. After surgery, the vision improved in three of the four eyes; in two, it improved by one line, and one improved by three lines, while the fourth eye had the same vision before surgery (20/100). The vitritis improved in all four eyes; two disappeared and two had grade 1 vitritis. The associated CME improved only in one eye; two eyes had the same CME before surgery and one was worsened after surgery (Table 3). As regards the two eyes treated with previous repository corticosteroid and that had TPPV for the peeling of developed dense ERM, one improved in vision, vitritis, and CME after surgery, whereas the other eye improved only in vitritis. VA was maintained at the same level as before surgery but the CME worsened after the surgery.

Table 3.

Ocular Data of Group 3 (IRU Associated With Dense ERM Treated With TPPV)

| Variables | Eye 1 | Eye 2 | Eye 3 | Eye 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 35 | 48 | 36 | 36 |

| Sex | M | F | M | M |

| Eye | L | L | R | L |

| Follow-up, wk | 93 | 28 | 17 | 100 |

| VA | ||||

| Before | 20/125 | 20/100 | 20/40 | 20/125 |

| After | 20/100 | 20/100 | 20/32 | 20/100 |

| Macular edema | ||||

| Before | 2 DD | 1.5 DD | 3.5 DD | 4 DD |

| After | 2 DD | 2.5 DD | 2.5 DD | 4 DD |

| Vitritis | ||||

| Before | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| After | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Eyes 2 and 3 were previously treated with posterior sub-Tenon injection of Depo-Medrol.

IRU = immune recovery uveitis; ERM = epiretinal membranes; TPPV = trans pars plana vitrectomy; VA = visual acuity.

Discussion

With the advent of HAART, patients with AIDS are enjoying improvement in their immune system with falling of their HIV viral load and rising of their CD4 cell count. Unfortunately, at this time these patients may have a profound drop in their vision due to the development of IRU and its complications. The prevalence of immune recovery uveitis/vitritis varies considerably by center.6,13 Immunologically, T cells are present in the inflamed sites.14,15 We performed a longitudinal cohort study of 18 eyes of 13 patients with IRU associated with macular complications. To our knowledge, this is the largest study performed on this group of patients as regards their number and their follow-up period. We used a graded approach to patients depending on severity of disease. Patients with mild IRU whose VA was better than 20/30 showed spontaneous improvement or at least stabilization in their VA and vitritis at the end of their follow-up period. Five of six eyes had VA of 20/20 at the end of the follow-up. The vitritis also resolved in four of six eyes. The other two eyes had only mild grade 1 residual vitritis.

In contrast, CME showed spontaneous improvement in only three eyes (50%) with complete resolution of the edema in two of them. In the remaining three eyes, CME was persistent. Epiretinal membrane was not a major problem in these mild cases (Table 1). Only one eye developed mild ERM in the form of parafoveal surface changes that required no intervention. Zegans et al reported that IRU is a transient inflammatory process that resolves completely within 6 weeks irrespective of treatment modality.5 This may apply to this group of mild cases but it does not explain the persistence of CME in half of these patients. Also, CME was not detected clinically in any of Zegans et al's patients, as they did not perform fluorescein angiography. They noted that the vitreous inflammatory reaction may limit the view of the fundus in these patients.

The second group in our study included patients with more severe inflammatory changes with VA of 20/30 or worse due predominantly to CME. This group was treated with a series of posterior sub-Tenon injections of repository corticosteroids. The main advantage of periocular corticosteroids is the production of therapeutic local drug levels to avoid the potential problems of systemic corticosteroids in these immunosuppressed patients. In our study, repository corticosteroids appeared to improve vitritis with decline in inflammatory cells in 60% of treated eyes. However, this treatment had a lesser effect on the VA, with improvement in only 40% of the treated eyes. In addition, macular edema was resistant to steroid injections. None of the eyes showed complete resolution of the edema and partial improvement was seen in only two eyes (20%). In a previous study we reported three cases of CME: one improved without treatment, one improved with oral corticosteroids, and the last one improved after posterior sub-Tenon injections of Depo-Medrol.4 However, in this study we have a larger number of eyes and longer follow-up period.

Henderson and Mitchell reported improvement in four patients with CME associated with IRU after repository corticosteroid injection.9 However, in that study, the CME was resistant to steroid injection and improvement occurred after the addition of oral acetazolamide to the treatment. We did not treat our patients with oral acetazolamide. It may be of limited value in these patients as the drug can have long-term side effects and the CME associated with IRU has a chronic course.

In a study by Nguyen et al,15 four eyes were reported to have IRU associated with CME. CME improved in two of them (50%). In the other two patients, the CME persisted despite aggressive therapy with topical, periocular, and systemic corticosteroids.15 The exact cause of resistance of CME associated with IRU to various modalities of treatment is unknown. Canzano et al7 reported two cases of IRU associated with CME, which failed to respond to all modalities of treatment including topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory, topical prednisolone acetate drops, and posterior sub-Tenon injection of triamcinolone, 40 mg/mL. The authors suggested that the reason for this persistence of CME was the vitreomacular traction syndrome, as shown by dynamic B scan ultra-sonography. TPPV was performed in both eyes with subsequent improvement.7

Kupperman and Holland suggested that continued, aggressive anticytomegalovirus therapy for a prolonged time after initiation of potent antiretroviral therapy may reduce the rate or severity of IRU. They recommended further investigation to clarify this point.16

In our study, we performed vitrectomy mainly for dense ERM development as a complication of IRU. Vitritis improved in all eyes after surgery. VA also improved in three out of four eyes, which may be attributed to the successful peeling of the ERM and also to the removal of the vitreous inflammatory cells. However, vitreous surgery did not always improve the angiographic CME in this group of patients. Partial improvement in CME occurred only in one case. Therefore, if the cortical vitreous condensation and traction were the main pathogenic factors associated with CME, we would expect improvement in CME, which did not occur.

We recognize that many of our patients were treated with cidofovir and that this drug, regardless of route of administration, may contribute to IRU. Our numbers are too small to determine whether cidofovir-treated eyes had different outcomes. Better control of CMV and potentially smaller lesion size may also reduce the risk of IRU.17

In conclusion, a graded treatment algorithm seems appropriate for eyes with macular change due to IRU.18,19 Mild cases have a tendency to improved vision with less vitreous inflammation without treatment. For eyes with macular edema sufficient to reduce vision below 20/30, corticosteroid injections may be effective in reducing vitritis but do not cause resolution of angiographic CME. In cases with dense ERM that develop as a complication of IRU, vitreous surgery may improve vision. It is of note that established CME associated with IRU appears to have a chronic course that is resistant to treatment. The numbers were too small to carry out a formal statistical analysis. We do not think such an analysis is appropriate for this type of study. We recognize that only a randomized clinical trial could definitively answer the issue of natural risk and treatment; however, given the relatively small number of patients and the heterogeneous nature of the disease, such a trial will be difficult to perform.

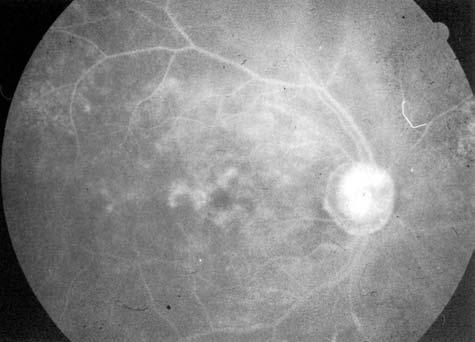

Fig. 2.

Late phase fluorescein angiogram shows persistence of cystoid macular edema 6 months after its onset and after four injections of repository corticosteroids. The Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study visual acuity declined from 20/40 to 20/60 despite this intensive treatment.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the National Eye Institute EY07366 (W.R.F.), the University-wide AIDS Research Program, University of California, grant no. MD99-SD-1022 (M.-K.S., F.J.T.), and the Center for AIDS Research grant no. 5P 30 AI36214-08 (F.J.T.).

References

- 1.Kupperman BD, Petty JG, Richman DD, et al. Correlation between CD4 counts and prevalence of cytomegalovirus retinitis and human immunodeficiency virus related non-infectious retinal vasculopathy in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;115:575–582. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoover DR, Peng Y, Saah A, et al. Occurrence of cytomegalovirus retinitis after human immunodeficiency virus immunosuppression. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:821–827. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jabs DA, Enger C, Bartlett JG. Cytomegalovirus retinitis and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:75–80. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070010077031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karavallas MP, Lowder CY, Macdonald JC, et al. Immune recovery uveitis associated with inactive cytomegalovirus retinitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:169–175. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zegans ME, Walton RC, Holland GN, et al. Transient vitreous inflammatory reactions associated with combination antiretroviral therapy in patients with AIDS and cytomegalovirus retinitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125:292–300. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karavellas MP, Plummer DJ, Macdonald JC, et al. Incidence of immune recovery uveitis in cytomegalovirus retinitis patients following institution of successful highly active anti-retroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:697–700. doi: 10.1086/314639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canzano JC, Reed JB, Morse LS. Vitreomacular traction syndrome following highly active antiretroviral therapy in AIDS patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Retina. 1998;18:443–447. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199809000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson MR, Erskine D, Hawkins DA, et al. Treatment with corticosteroids: a risk factor for the development of clinical CMV disease in AIDS. AIDS. 1993;7:375–378. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199303000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson HWA, Mitchell SM. Treatment of immune recovery uveitis with local steroids. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:540–545. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.5.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karavellas MP, Azen SP, Macdonald C, et al. Immune recovery uveitis and uveitis in AIDS: clinical predictors, sequelae and treatment outcomes. Retina. 2001;21:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nussenblatt RB, Palestine AG, Chan CC, Roberg F. Standardization of vitreal inflammatory activity in intermediate & posterior uveitis. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:467–471. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weizz JM, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, et al. Ketorolac treatment of pseudophakic cystoid macular edema identified more than 24 months after cataract extraction. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1656–1659. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90366-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitcup SM. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. JAMA. 2000;283:653–657. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.5.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mutimer HP, Akatsuka Y, Manley T, et al. Association between immune recovery uveitis and a diverse intraocular cytomegalovirus-specific cytotoxic T cell response. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:701–705. doi: 10.1086/342044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen QD, Kempen JH, Bolton SG, et al. Immune recovery uveitis in patients with AIDS and cytomegalovirus retinitis after highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:634–639. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kupperman BD, Holland GN. Immune recovery uveitis [editorial] Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:103–106. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00537-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jabs DA, Van Natta ML, Kempen JH, et al. Characteristics of patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:48–61. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karavellas MP, Song M, Macdonald JC, Freeman WR. Long-term posterior and anterior segment complications of immune recovery uveitis associated with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00528-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunn JP. Immune recovery uveitis. Hopkins HIV Rep. 2001;13:9–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]