Abstract

Background

Initiatives to improve end-of-life care are hampered by our nascent understanding of what quality care means to patients and their families. The primary purpose of this study was to describe what seriously ill patients in hospital and their family members consider to be the key elements of quality end-of-life care.

Methods

After deriving a list of 28 elements related to quality end-of-life care from existing literature, focus groups with experts and interviews with patients, we administered a face-to-face questionnaire to older patients with advanced cancer and chronic end-stage medical disease and their family members in 5 hospitals across Canada to assess their perspectives on the importance. We compared differences in ratings across various subgroups of patients and family members.

Results

Of 569 eligible patients and 176 family members, 440 patients (77%) and 160 relations (91%) agreed to participate. The elements rated as “extremely important” most frequently by the patients were “To have trust and confidence in the doctors looking after you” (55.8% of respondents), “Not to be kept alive on life support when there is little hope for a meaningful recovery” (55.7%), “That information about your disease be communicated to you by your doctor in an honest manner” (44.1%) and “To complete things and prepare for life's end — life review, resolving conflicts, saying goodbye” (43.9%). Significant differences in ratings of importance between patient groups and between patients and their family members were found for many elements of care.

Interpretation

Seriously ill patients and family members have defined the importance of various elements related to quality end-of-life care. The most important elements related to trust in the treating physician, avoidance of unwanted life support, effective communication, continuity of care and life completion. Variation in the perception of what matters the most indicates the need for customized or individualized approaches to providing end-of-life care.

Over the past decade, several initiatives have been established to attempt to improve end-of-life care.1–3 Quality of life for terminally ill patients,4,5 quality of death and dying6,7 and quality care at the end of life8 are related concepts that have been evaluated in these efforts to improve end-of-life care. Quality of care at the end of life is distinguished from quality of life and of death by its focus on the optimization of care and satisfaction with care, clearly linking quality measurement and quality improvement.6,9

Unfortunately, initiatives to improve satisfaction with end-of-life care remain hampered by our nascent understanding of what quality care means to patients and their families, and how it is best measured.9–11 Several experts and professional societies have attempted to define the specific components and related areas (domains) involved in quality end-of-life care;12–16 in contrast, patient and family perspectives are surprisingly lacking.

Most previous studies of quality have focused on outpatients and people with cancer.17–21 We recently documented that most Canadians (> 70%) die in hospitals, and the majority of decedents are elderly patients who died from causes unrelated to cancer.22,23 The trajectory of a patient dying from cancer differs from one dying from other, chronic, end-stage medical conditions.24 Thus, issues deemed important to quality end-of-life care that were identified by previous investigators may not be generalizable to seriously ill patients with advanced disease other than cancer, who have a more uncertain prognosis.

The primary purpose of this study was to describe what seriously ill patients admitted to hospital and their family members consider the key elements of quality end-of-life care. Our secondary objectives included exploring whether differences in ratings of importance exist between patient and caregiver subgroups and between patients and family members.

Methods

We designed a cross-sectional survey to be conducted at 5 tertiary care teaching hospitals across Canada. From west to east, they were St. Paul's Hospital, Vancouver, BC; Royal Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton, Alta.; Toronto General Hospital, Toronto, and Kingston General Hospital, Kingston, Ont.; and Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, Halifax, NS. Each site admitted seriously ill patients to the acute care wards under the care of a primary service and had regional or hospital palliative care consultation services available upon request. The research ethics board at each participating institution approved the study design. All study subjects provided written informed consent.

Eligibility criteria for the study were chosen to define a patient population having advanced disease, with a 50% probability of survival at 6 months.25 Although our focus was on elderly patients, some patients with advanced cancer or end-stage medical disease would be younger than 65 years; to enhance the feasibility and generalizability of the study, we lowered the age limit to 55. Patients were therefore eligible if they were aged 55 years or older; were expected to stay in hospital for at least 72 hours; and had an advanced stage of 1 or more of these 4 diseases:

• Chronic obstructive lung disease, with at least 2 of these 4 conditions: baseline Paco2 of at least 45 mm Hg; cor pulmonale; an episode of respiratory failure during the past year; forced expiratory volume in 1 second of 0.75 L or less

• Congestive heart failure, with New York Heart Association class IV symptoms or a left-ventricular ejection fraction measured at 25% or less

• Cirrhosis, confirmed by imaging studies or documentation of esophageal varices, and any of hepatic coma, Child's class C liver disease or Child's class B liver disease with gastrointestinal bleeding

• Cancer, diagnosed as metastatic cancer or stage IV lymphoma

On the basis of a chart review of a patient's progress notes, conversation with staff or, in some circumstances, direct evaluation of the patient, we excluded participants likely to have language or cognitive difficulties. Consenting patients identified a family member or other close person who provided some form of care in the home setting, if such a relationship existed. There was no age restriction for family members or social caregivers to participate in the study.

To develop the questionnaire, we first reviewed published taxonomies of quality end-of-life care to generate an initial list of key care elements.12–15 Additional elements were then generated from further literature review and discussion with the multidisciplinary End of Life Research Working Group at Queen's University, Kingston, Ont. Next, to determine whether any elements had been overlooked or were ambiguously phrased, we conducted 12 semistructured interviews with eligible seriously ill patients in hospital.

Finally, we developed a comprehensive list of 28 elements of care, organized into 5 domains: medical and nursing care; communication and decision-making; social relationships and support; meaningful existence; and advance planning of care. We used response options to assess differing degrees of importance using a 5-point ordinal scale: 1 = not at all important; 2 = somewhat important; 3 = important; 4 = very important; and 5 = extremely important. The draft questionnaire was then tested extensively to assess comprehensiveness, readability, sensibility and clarity in focus groups with health care providers and in individual interviews with patients and family members.

To collect data, a research nurse was hired at each hospital and trained by project staff to conduct the interview and perform study procedures. The research nurses screened medical records of current inpatients to identify potential participants and confirmed their suitability with the attending physician or assigned bedside nurse. Consecutive patients who seemed emotionally, physically and cognitively able to participate were approached for informed consent, as were the designated family members of enrolled patients. Both patients and family members were then administered the questionnaire in separate, face-to-face interviews.

The first item on the questionnaire was an open-ended question; the research nurse asked the interviewee to talk about the illness and treatments. Next, the nurse presented the respondent with a list of the 28 elements and asked them to rate each element for its level of importance, in their own eyes, to end-of-life care. Except for pronouns (e.g., “his or her disease” instead of “your disease”), the family-member survey was identical to the patient survey; respondents were instructed to report their own views, not to offer proxy responses on behalf of the patient. The nurse also collected demographic data including age, sex, marital status, ethnicity, religion, education, admission diagnosis and functional status.26 Survival status at 6 months was determined by contacting the participating patients or their family or family doctor.

Because the main purpose of this study was descriptive, we set out to obtain a consecutive sample of 100 eligible patients in each of the 5 participating hospitals. A sample size of 100 was a convenience sample thought to be large enough to provide a representative sample of responses for each locale. For each survey question, we noted the frequency for each of the response options from 1 to 5, separately for both patients and family members. In tables, we ranked the elements according to the proportion of responding patients and family members who rated each element as 5 (extremely important).

Using Pearson's χ2 analysis27 we explored key differences in ratings of importance (the percentage of ratings of “extremely important” v. all other ratings) between groups of patients with different diagnosis categories (cancer v. other end-stage medical) and levels of family support (patients with a family caregiver v. those without), and different relationships to the patient of the family members responding (spouse, child or “other”). Finally we analyzed differences in ratings between patients and their corresponding caregivers, using McNemar's test for matched-pair data.28

Results

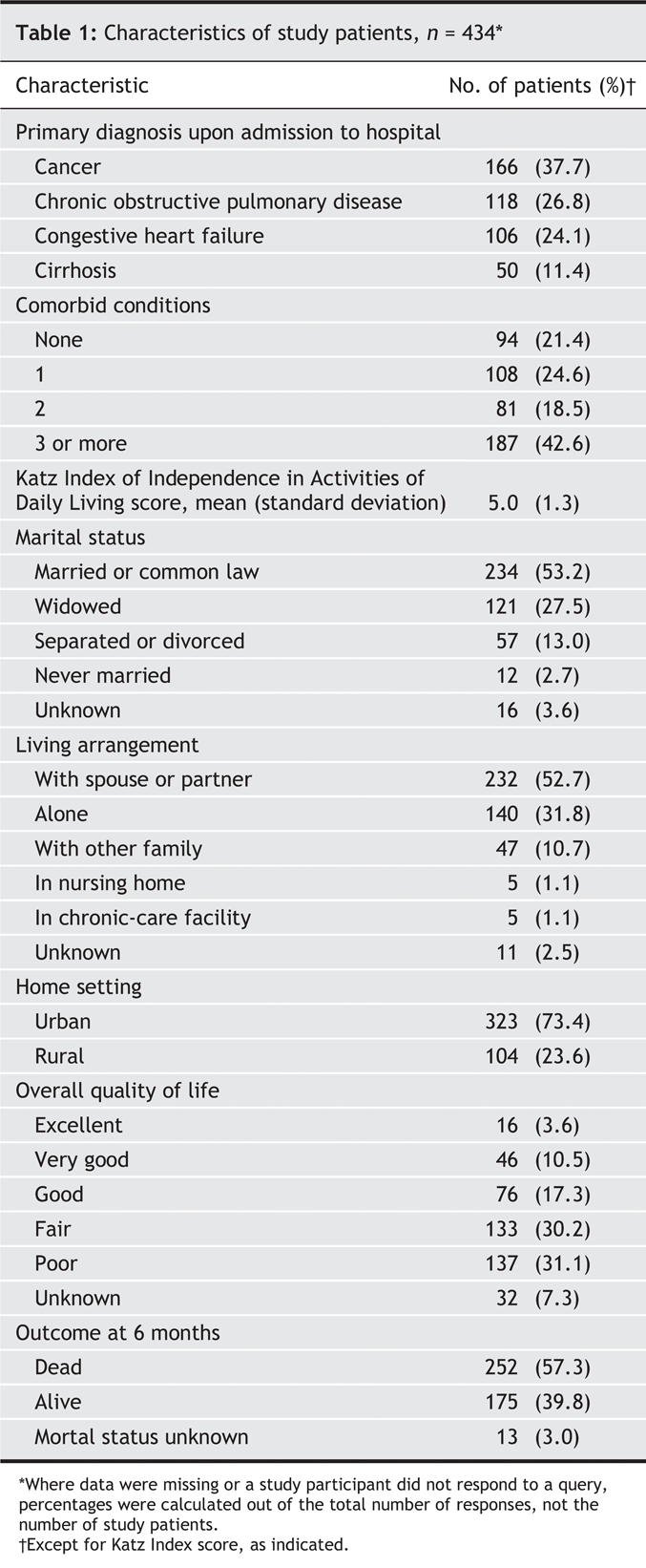

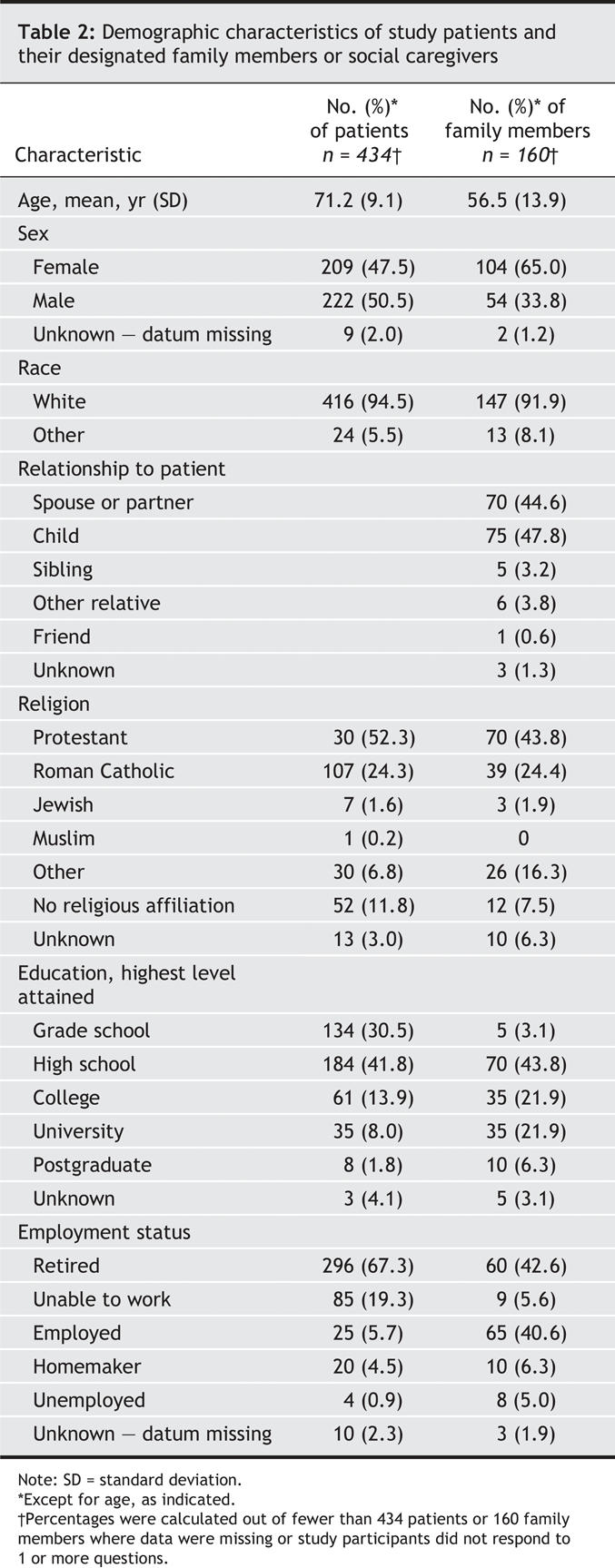

From November 2001 through June 2003, 569 eligible patients were identified and approached for consent at the 5 hospitals; 440 consented, for an overall response rate of 77%. One patient died before the scheduled interview, and 5 were withdrawn by the research nurse during the interview itself, when the nurse decided that the patient had insufficient grasp of the format of the study; this left 434 for data analysis. Among the consenting patients, 226 (51%) had a family member (or, in at least 1 case, another socially close caregiver) who would potentially be visiting the hospital. We were able to approach, make an appointment with and interview only 176 visiting family members for consent; 160 agreed to participate, which yielded a response rate in that group of 91%. Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the demographics of the study patients and their family members.

Table 1

Table 2

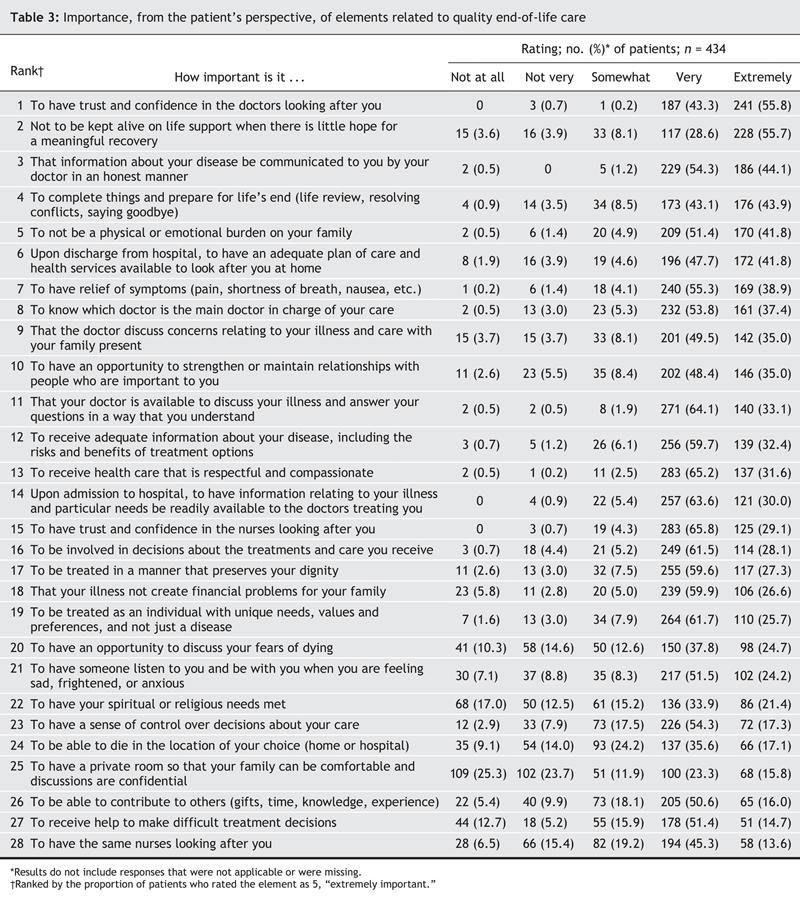

The patients' ratings of importance of the elements of end-of-life care are presented in Table 3. Those most frequently rated as 5 (extremely important) by the patients were “To have trust and confidence in the doctors looking after you,” “Not to be kept alive on life support when there is little hope for a meaningful recovery” (both rated extremely important by about 56% of study patients) and “That information about your disease be communicated to you by your doctor in an honest manner” (44%). The elements least frequently rated as extremely important were “To have the same nurses looking after you,” “To receive help making difficult treatment decisions” and “To be able to contribute to others” (14%–16%).

Table 3

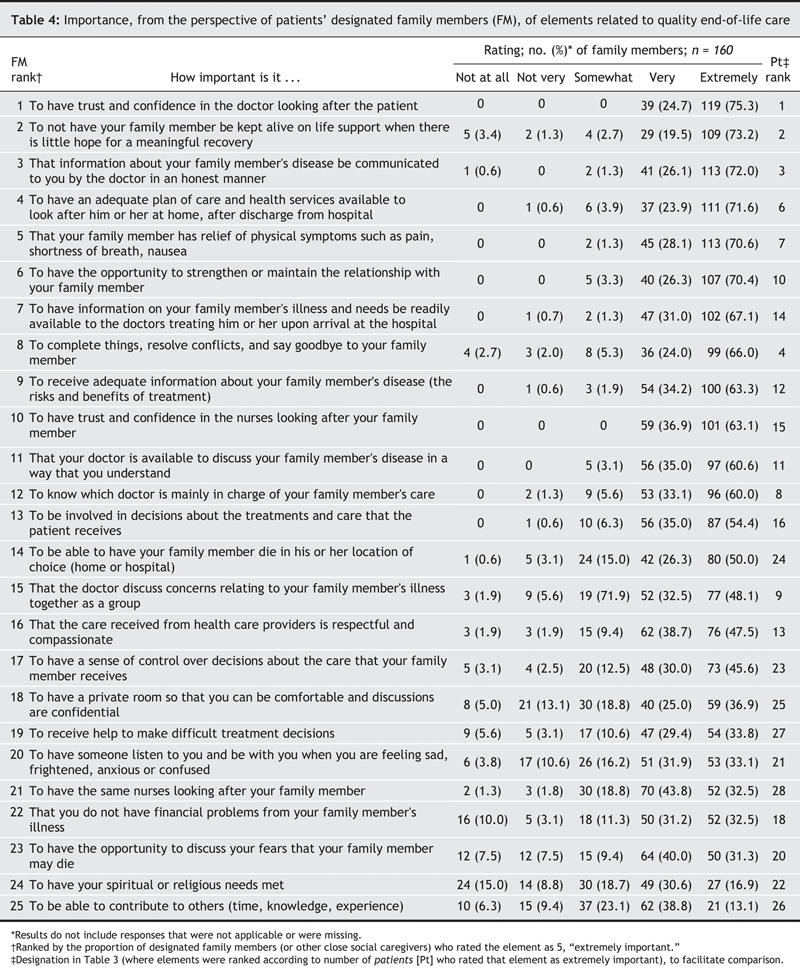

Table 4 presents the elements of end-of-life care that were rated as extremely important by family members according to their own perspective. The 3 elements most frequently rated as extremely important (by 72%– 75% of family members) were “To have trust and confidence in the doctors looking after the patient,” “Not to be kept alive on life support when there is little hope for a meaningful recovery [by the patient]” and “That information about your family member's disease be communicated to you by the doctor in an honest manner.” The 3 least frequently rated as extremely important by family members were “To be able to contribute to others — gifts, time, knowledge, experience” (14%), “To have your spiritual or religious needs met” (19%) and “To have the opportunity to discuss your fears that your family member may die” (33%).

Table 4

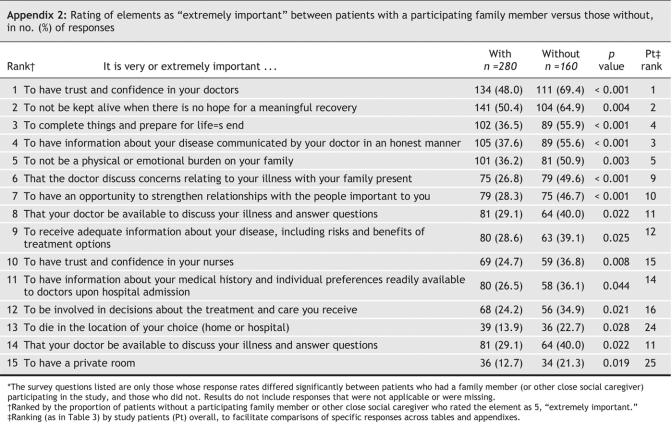

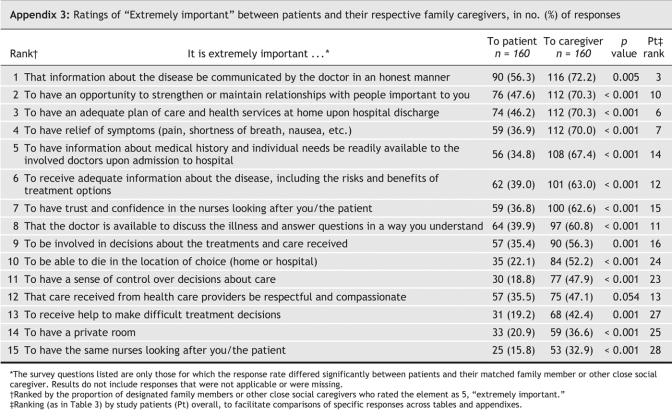

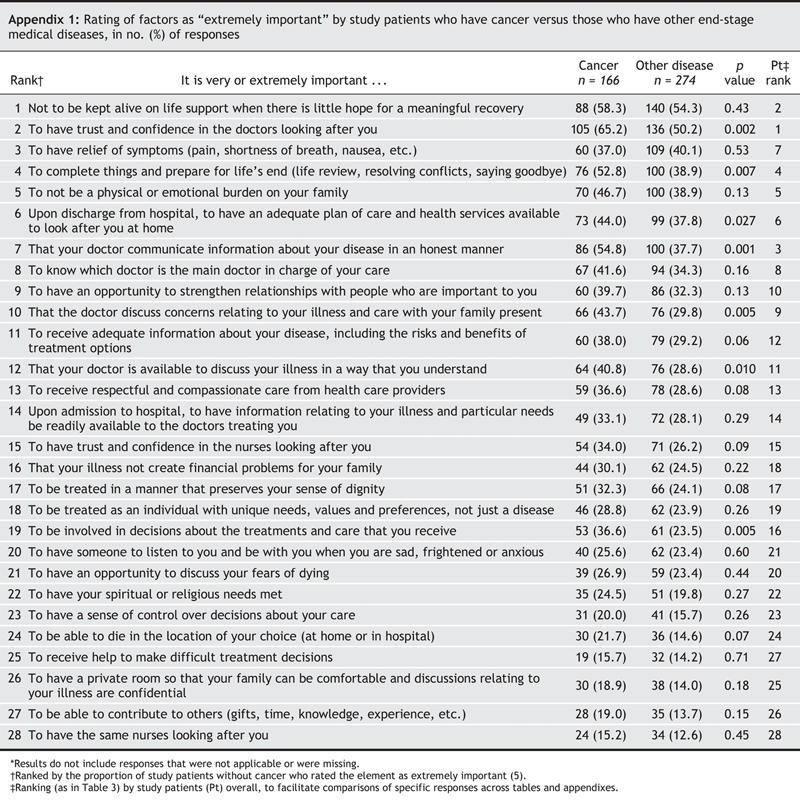

Compared with subjects who had other types of advanced disease, patients with cancer were more likely to rate several elements as extremely important; these are listed in Appendix 1. We also observed differences in ratings of importance between patients who had family members participating in the study and those who did not (see Appendix 2). For each patient and paired family member who participated in the study, we analyzed for differences in perspectives (Appendix 3). If a caregiver was considered to be “other,” compared with the patient's spouse or child, they were much less likely to rate “To have the opportunity to discuss your fears that your family member may die” (p = 0.020) and “To have an opportunity to strengthen or maintain relationships with people who are important to you” (p = 0.003) as 5, extremely important.

Interpretation

We surveyed a large cohort of seriously ill patients in hospital with advanced disease and, where available, a family member for each, and found that the most important elements of end-of-life care from their perspectives related to trust in the treating physician, avoidance of unwanted life support, effective communication, continuity of care, and life completion. This is not to say that the other elements presented were unimportant; rather that, relative to these, elements such as having a private room or being able to die in the location of choice were rated as less important.

Participants in our study found it extremely important that they have trust and confidence in the physicians caring for them or their loved ones. Although this study does not shed light on how a trusting relationship with a patient can be built, it does highlight the importance of trust. This finding is consistent with recent work on the quality of death and dying,29 which found that better clinician–patient and clinician– family relationships were associated with better ratings of the experience by family members of the dying patient.

Comparing our findings with those of other studies that evaluated patient and family perspectives on quality end-of-life care yields some interesting observations. These studies share a common purpose but notable differences, not only in the primary findings but also in the patient populations studied and the methods used. Whereas previous studies elicited the perspectives of outpatients with chronic disease, cancer or HIV and their bereaved families,17–19,21 we studied a population of older hospital inpatients with advanced medical disease and their family members. Since the experience of dying in Canada (and elsewhere) is largely a hospital experience, one of the purposes of this project was to determine the extent to which the elements identified in previous publications were key indicators of quality end-of-life in-hospital care for seriously ill patients and their families. The factors of trust and confidence in physicians, adequacy of discharge planning and honesty of communication that were identified in our study as extremely important were not discussed in prior studies.17–19,21

Most of the earlier studies in this field were qualitative; we, however, conducted a quantitative survey that enables us to grasp the relative importance of the various elements. Singer17 and Teno21 and their respective groups put forward the notion that quality of end-of-life care is associated with having control over decisions. We observed that few patients considered control over decision-making to be extremely important (17.3%, ranked 23rd of 28) and even fewer valued help in making difficult treatment decisions (14.7%, ranked 27th of 28). “Having an opportunity to contribute to others” seemed to be an important construct in prior studies, but was rated as extremely important by few of our respondents. As much as precise definitions may slightly vary, some themes or domains and items have been consistent across all studies: symptom relief, strengthening relationships, relieving one's burden upon others, having an opportunity to complete things, say goodbye and bring closure to life, and avoiding a prolonged death.

Strengths of our study included the derivation of a more comprehensive overview of the important domains within quality end-of-life care, based on perspectives from a large population sampled from 5 major cities in Canada and involving patients from both rural and urban settings. In addition, our participating patients were indeed near the end of their lives (more than 50% died within 6 months), and response rates were high (77%–91%). The fact that both patients and family members labelled similar elements as extremely important added credibility to our findings. An advantage of our quantitative survey over past qualitative work in the area is the emergence of an understanding of the importance of these various elements relative to each other.

We also found significant variation in ratings of importance between different groups of patients, different groups of family members, and between patients and family members of the same family (see Appendixes). Undoubtedly, we could have done more subgroup comparisons based on other important demographics (e.g., age of patient, health of caregiver, degree of family social support); we therefore consider this an illustrative rather than an exhaustive list of differences. Our observations are consistent with a recent study29 that used time trade-off techniques involving a general population, which showed considerable interpersonal variation in how much people value end-of-life care, and a qualitative study30 that demonstrated differing views of a “good death” and a “bad death” from the older patient's perspective. These findings of individual variation are material to quality improvement initiatives in end-of-life care. They suggest that the tools we need to measure quality of care should include individualized assessments for us to understand what each patient (and their family) experiences, what matters to them and what we can do to improve their end-of-life care. “One size” may not fit all, and assessments and care plans need to have an individualized patient and family-centred approach, similar to the approaches used in the assessment and management of pain and other symptoms24 and those being developed in response to the emerging interest in individualized quality-of-life assessments.31,32

Limitations of our study include the fact that patient and family preferences may change as death approaches. We also acknowledge that individual ratings of importance may be influenced by deficiencies in current care. In effect, what matters most are the elements of care that are currently the least well provided. Moreover, our method of ranking items may be considered suboptimal. However, having the patients themselves sort through 28 items to determine their relative ranking seemed impractical. Conducting multiple tests of significance to illuminate subgroup differences may have led to spurious findings; however, in our estimation it was more important to examine the variation in importance than the absolute differences in and between subgroups. Finally, our predominantly white sample drawn from tertiary care hospitals may limit the generalizability of our findings.

In conclusion, seriously ill patients and family members have defined key issues related to quality end-of-life care. The results of our study have significant clinical and policy implications. If we are correct, and quality in end-of-life care has more to do with enhancing relationships and improving communication between the attending physician and the seriously ill patient and family, promoting patient autonomy with tools such as advance directives or living wills may not be the optimal approach. If preference for location of death is really less of an issue than not being a burden on family and friends, then increasing home-care capacity for palliative care may be moving in the wrong direction. Initiatives to target improvement of the most important themes indentified in our study will likely result in an improvement in overall quality care at the end of life. However, our findings suggest that a more tailored or patient-specific approach to improving quality may be required, given the variability in preferences between patient groups and between patients and family members. We clearly need more research into optimal professional behaviours and communication strategies, which, from a patient's perspective, build relationships of trust and satisfy information needs and decision-making roles.

Acknowledgments

As well as thanking all the investigators listed in Appendix 1, we offer our sincere appreciation to all the study participants: the patients and family members who selflessly participated in spite of all their grave personal difficulties.

Appendix 1.

Appendix 2.

Appendix 3.

Footnotes

Editor's take

• What are the components of good quality end-of-life care? There are many opinions, but few studies have asked patients and their family caregivers directly.

• In-depth interviews of patients and caregivers revealed that the elements rated most frequently as “extremely important” were to have trust and confidence in their physicians, not to be kept alive on life support when there is little hope for a meaningful recovery, to have information about their disease be communicated by their doctor in an honest manner, symptom relief and to prepare for life's end by resolving conflicts and saying goodbye. Having control over treatments and where a patient dies were chosen infrequently.

Implications for practice: The variations in perceptions of what matters most indicate a need for customized or individualized approaches to providing end-of-life care.

An abridged version of this article is available in the Feb. 28, 2006, issue of CMAJ.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors to the study: Dr. Daren Heyland, principal investigator; Drs. Joan Tranmer, Sam Shortt, Sandra Taylor and Deborah Feldman-Stewart, coinvestigators; Deborah Pichora, study coordinator; and Dianne Groll and Dr. Miu Lam, statisticians, Queen's University, Kingston, Ont. Dr. Peter Dodek, coinvestigator, and Judith Edgar, research assistant, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC. Dr. Jim Kutsigiannis, coinvestigator, and Sara Currie, research assistant, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alta. Dr. Neil Lazar, coinvestigator, and Andrea Matte-Martin, research assistant, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont. Dr. Graeme Rocker, coinvestigator, and Gail Sloane, research assistant, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, the acquisition and analysis of study data, and the preparation and critical revision of this article.

Funding for this study was provided by the National Health and Research Development Program of Canada.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Daren K. Heyland, Angada 4, Kingston General Hospital, Kingston ON K7L 2V7; fax 613 548-1351; dkh2@post.queensu.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.Open Society Institute. Project on death in America. Available: www.soros.org/initiatives/pdia (accessed 2005 Dec 5).

- 2.University of Montana. Promoting palliative care excellence in intensive care. Available: www.promotingexcellence.org (accessed 2005 Dec 5).

- 3.Carstairs S, Beaudoin GA; Subcommittee to Update “Of Life and Death” of the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology. Quality end-of-life care: the right of every Canadian. Final report. Ottawa: Senate of Canada; 2000. Available: www.parl.gc.ca/36/2/parlbus/commbus/senate/com-e/upda-e/rep-e/repfinjun00-e.htm (accessed 2006 Feb 1).

- 4.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Strobel MG, et al. The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire: a measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease. A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med 1995;9:201-19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Liao Y, McGee DL, Cao G, et al. Quality of the last year of life of older adults: 1986 vs 1993. JAMA 2000;283:512-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Patrick DL, Curtis R, Engelberg RA, et al. Measuring and improving the quality of dying and death. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:410-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Smith R. A good death: an important aim for health services and for us all. BMJ 2000;320:129-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Sulmasy DP, McIlvane JM, Pasley PM, et al. A scale for measuring patient perceptions of the quality of end-of-life care and satisfaction with treatment: the reliability and validity of QUEST. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;23:458-70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Lunney JR, Foley KM, Smith TJ, et al, editors; for the National Research Council. Describing death in America: what we need to know. Washington: National Academy Press; 2003. [PubMed]

- 10.Center to Improve Care of the Dying. Satisfaction with quality of care. In: Center for Gerontology and Health Care Research, Brown Medical School. Toolkit of instruments to measure end-of-life care. Available: www.chcr.brown.edu/pcoc (accessed 2006 Jan 26). Providence (RI): Brown University.

- 11.Lo B. Improving care near the end of life. Why is it so hard? JAMA 1995;274:1634-6. [PubMed]

- 12.Emanuel EL, Emanuel LL. The promise of good death. Lancet 1998;351(Suppl 2):21-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Lynn J. Measuring quality of care at the end of life: a statement of principles. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:526-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Field MJ, Cassel CK, editors; for the Institute of Medicine. Approaching death: improving care at the end of life. Washington: National Academy Press; 1997. [PubMed]

- 15.Clark D. Between hope and acceptance: the medicalisation of dying. BMJ 2002;324:905-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, et al. Dignity in the terminally ill: a cross-sectional, cohort study. Lancet 2002;360:2026-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patient's perspectives. JAMA 1999;281:163-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, et al. In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:825-32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians and other care providers. JAMA 2000;284:2476-82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Kristjanson LJ. Indicators of quality of palliative care from a family perspective. J Palliat Care 1986;1:8-17. [PubMed]

- 21.Teno JM, Casey VA, Welch LC, et al. Patient-focused, family-centered end-of-life medical care: views of the guidelines and bereaved family members. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001;22:738-51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Heyland DK, Lavery JV, Tranmer J, et al; for the Queen's/KGH End of Life Research Working Group. Dying in Canada: Is it an institutionalized, technologically supported experience? J Palliat Care 2000;16:S10-6. [PubMed]

- 23.Heyland DK, Lavery JV, Tranmer J, et al; the Queen's/KGH End of Life Research Working Group. The final days: an analysis of the dying experience in Ontario. Ann R Coll Physicians Surg Can 2000;33:356-61.

- 24.Tranmer JE, Heyland DK, Dudgeon D, et al. Measuring the symptom experience of seriously ill cancer and noncancer hospitalized patients near the end of life with the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;25:420-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.SUPPORT Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. JAMA 1995;274:1591-8. [PubMed]

- 26.Katz S, Stroud MW. Functional assessment in geriatrics: a review of progress and directions. J Am Geriatr Soc 1989;37:267-71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers Group; 1990.

- 28.Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. New York: Wiley Interscience Publications; 1990.

- 29.Bryce CL, Loewenstein G, Arnold RM, et al. Quality of death: assessing the importance placed on end of life treatment in the intensive care unit. Med Care 2004;42:423-31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Vig EK, Davenport NA, Pearlman RA. Good deaths, bad deaths, and preferences for the end of life: a qualitative study of geriatric outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1541-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Joyce CRB, Hickey A, McGee HM, et al. A theory-based method for the evaluation of individual quality of life: the SEIQoL. Qual Life Res 2003;12:275-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Byock IR. Measuring quality of life for patients with terminal illness: the Missoula– VITAS quality of life index [review]. Palliat Med 1998;12:231-44. [DOI] [PubMed]