Abstract

The energy of interaction between complementary nucleotides in promoter sequences of E. coli was calculated and visualized. The graphic method for presentation of energy properties of promoter sequences was elaborated on. Data obtained indicated that energy distribution through the length of promoter sequence results in picture with minima at −35, −8 and +7 regions corresponding to areas with elevated AT (adenine-thymine) content. The most important difference from the random sequences area is related to −8. Four promoter groups and their energy properties were revealed. The promoters with minimal and maximal energy of interaction between complementary nucleotides have low strengths, the strongest promoters correspond to promoter clusters characterized by intermediate energy values.

Keywords: DNA sequence, Promoter strength, Nucleotide pair energy, −35 sequence, −10 sequence, +7 sequence

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial protein-coding genes must be differentially expressed during the cell cycle, in response to a wide variety of extracellular signals. Initiation of transcription by RNA polymerase (RNAP) requires cis-acting DNA elements including core promoters. Core prokaryotic promoters, especially from Escherichia coli for RNA polymerase complexes with the factor σ 70 usually are situated between −60 to +20 base pair from the transcription start site (+1), have two most important transcription initiation sites: at the −35 position and at −10 region (the Pribnow box). The sequences of −10 and −35 sites may affect the binding of RNA polymerase and the formation of open complexes (Babb et al., 2004).

The Escherichia coli RNAP core enzyme can initiate the elongation stage of transcription, but only the holoenzyme containing a σ factor trigers the specific transcription initiation. Promoter recognition by the holoenzyme containing the major σ factor (σ 70) occurs through interactions of σ with up to three promoter modules. The notion of promoter strength was introduced in order to evaluate the promoter ability to initiate transcription. The problem of the connection between promoter strength and its structure was intensively investigated in the 1980s. The −10 hexamer (consensus sequence 5′-TATAAT-3′) is recognized by σ region 2.3~2.4 (Burr et al., 2000); the extended −10 region (consensus 5′-TGTGn-3′) is recognized by σ region 3.0 (Murakami et al., 2002); and the −35 hexamer (consensus 5′-TTGACA-3′) is recognized by σ region 4.2 (Campbell et al., 2002). The C-terminal domains of the two α subunits (α CTDs) at some promoters interact with specific sequences referred to as upstream elements located upstream of the −35 hexamer (Gourse et al., 2000).

The rate-limiting step in transcriptional initiation typically is opening the promoter DNA to expose the template strand. Promoter mutations are known to reduce opening rates. Junction binding activity is contained within the sigma factor component of the holoenzyme (Guo and Gralla, 1998). The site −11 is known to be critical for open complex formation. It is highly conserved in promoters and substitutions there have by far the strongest effect in diminishing rates of open complex formation (Roberts and Roberts, 1996).

The promoter strength may be determined by different ways. Using the in vitro mixed transcription system Kajitani and Ishihama (1983) determined the two parameters of the promoter strength, i.e., the rate of open complex formation between RNA polymerase and promoter, and the saturation level of the open complex formation at equilibrium. Vogel et al.(2002) defined the overall promoter strength as the rate at which the open complex RPo of RNAP·σ 54 (R) at a given promoter P is formed in a multi-step reaction R+P⇔RPc⇔…⇔RPo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA sequences

We obtained 106 Escherichia coli promoter sequences using σ 70 subunit from the Regulon database (©2004, CIFN/UNAM all Rights Reserved. RegulonDB DataBase V. 4.0, 02-FEB-05) thanks to the courtesy of the Regulon database administration. All promoter sequences were transcribed with the aid of σ 70. Promoter strength (the promoter ability to initiate transcription) was measured with the help of fluorescent labelling method in microarray experiments on the total transcripts of E. coli. Promoter strength was determined in arbitrary units reflecting the fluorescence intensity (Kanehisa et al., 2004; Mori et al., 2000). Promoter strength data obtained from KEGG EXPRESSION database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/expression/) which contains microarray data obtained by the Japanese research community. Orientation of promoter sequence in genome was determined as forward or reverse depending the gene position in the genome. As far as we know forward and reverse orientation is not connected with gene functioning.

The number of random sequences analyzed as the control variant was equal to 30. The number of forward promoter sequences was equal to 28 and the number of reverse sequences was equal to 34.

Computer analysis

We suggest the notion of promoter energy that is determined as a sum of energy of interaction of each nucleotide pair in promoter divided by nucleotide number. For analysis of AT-contents and energy of pair interaction in promoter sequences we applied the “sliding-window” method. The AT-contents and energy of pair interaction at the site of ten nucleotide pairs (window length) were summarized and the mean value of these parameters were estimated. On every next step the analyzed site at one base pair was shifted. The data for every stage are presented in the figures. Computer programs for obtaining random DNA sequences, programs for promoter sequences energy estimation, program for slide-window data investigation, program for estimation of standard errors and t-criterion were elaborated by Berezhnoy. Cluster analysis was realized by the computer program STADIA 3.0 (Borland Corporation, USA).

RESULTS

The names of promoters of E. coli and their corresponding numbers in our investigation are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The list of analyzed promoter sequences of E. coli

| Number of promoter sequence in the figures | Number of forward promoter sequence in Table 2 | Name of forward promoter sequence | Number of reverse promoter sequence in Table 2 | Name of reverse promoter sequence |

| 1 | 1 | AccA | 29 | AccD |

| 2 | 2 | AccB | 30 | Alas |

| 3 | 3 | Adk | 31 | AspC |

| 4 | 4 | Cfap1 | 32 | AstCp1 |

| 5 | 5 | ClpAp1 | 33 | AtpI |

| 6 | 6 | Cmk | 34 | CedAp |

| 7 | 7 | CorA | 35 | CysE |

| 8 | 8 | Efpp | 36 | DapA |

| 9 | 9 | Frrp | 37 | DapD |

| 10 | 10 | FxsAp | 38 | DppA |

| 11 | 11 | GalRp | 39 | DrpA |

| 12 | 12 | GlnS | 40 | FtsJp1 |

| 13 | 13 | ManA | 41 | Gnd |

| 14 | 14 | MraZp | 42 | HepAp |

| 15 | 15 | NohAp | 43 | Hiss |

| 16 | 16 | Pgi | 44 | HscB |

| 17 | 17 | Phe | 45 | Lep |

| 18 | 18 | PurA | 46 | LysP |

| 19 | 19 | Rep | 47 | MenAp |

| 20 | 20 | RplJ | 48 | NanAp |

| 21 | 21 | RplK | 49 | OtsB |

| 22 | 22 | RpoB | 50 | Pdx |

| 23 | 23 | RpoN | 51 | PheS |

| 24 | 24 | SbcB | 52 | PntA |

| 25 | 25 | ThrA | 53 | Pthp |

| 26 | 26 | TufB | 54 | PutA |

| 27 | 27 | Ung | 55 | RplT |

| 28 | 28 | YhcA | 56 | RpsJ |

| 29 | 57 | Smp | ||

| 30 | 58 | Spc | ||

| 31 | 59 | Str | ||

| 32 | 60 | SufAp | ||

| 33 | 61 | Upp | ||

| 34 | 62 | XseBp |

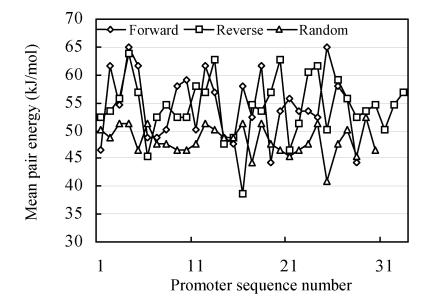

In the Fig.1 are data for specific mean energy of complementary base pair interaction in different promoters. These data vary in chaotic manner.

Fig. 1.

The specific free energy of complementary base pair interaction in different promoters (forward and reverse promoter sequences and random sequences)

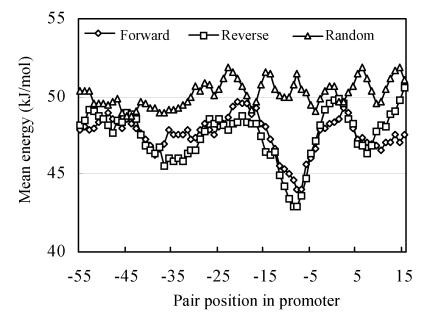

The distribution of the energy of interaction between base pairs through the length of promoter sequence was measured by the method of sliding window. The mean data for forward and reverse promoter sequences (number of forward sequences equals 28 and number of reverse ones equals 34) are presented in Fig.2. The mean energy of nucleotide pair is −29.33 kJ/mol for AT-pair and −70.35 kJ/mol for GC-pair (Kudritskaya and Danilov, 1976). As Fig.2 data show that the distribution of pair free energy of interaction in promoter sequences have three minimums. The one in the area between −40 and −30 window position relative to the beginning of transcription point (+1), a second one between −15 and −10 position, the last one between −4 and +10 position. These windows are situated in the most important areas of promoter sequence, and correspond to consensus sequences at −10, −35 and +10.

Fig. 2.

The mean energy per nucleotide pair depending on pair position in promoter sequence

The mean contents of AT-pairs is elevated in three areas: −35, −8 and +7 window position (Fig.3).

Fig. 3.

The mean contents of AT-pairs depending on window position in the promoter sequence

The t-criterion data on differences in nucleotide contents between forward and random sequences and between reverse and random sequences are presented in Fig.4. As one can see t-criterion for difference in nucleotide contents has two maximum in the area near −35 and −10 window position. In this area the energy differences between random and forward or reverse sequences are the most pronounced (Fig.2) because of the elevated concentration of AT-pairs (Fig.3).

Fig. 4.

The difference between random and forward or reverse promoter sequences (t-criterion)

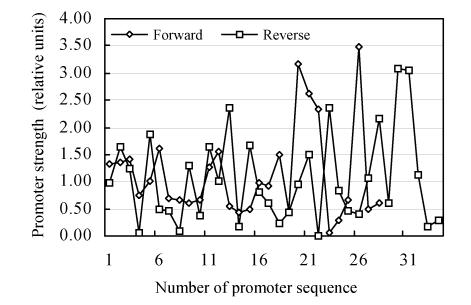

The mean data on promoter strength are presented in Fig.5.

Fig. 5.

The promoter strength

With the help of cluster analysis using the method of Euclidian distances determination we analyzed all promoter sequences by the character of mean energy of base pair interaction per nucleotide pair. The obtained data are presented in Table 2. We suggested that promoter sequences are divided into 3 and 4 clusters. We proposed such subdivision because existence of less than two clusters is impossible and the promoter sequences number was not large enough to divide our set of promoter sequences reliably in the more than 4 clusters. As one can see all clusters differ significantly in the mean energy of the complementary nucleotide interaction parameter. Our data indicate that the energy differences between clusters do not directly correspond to differences in their strengths. The promoters in clusters with minimal and maximal energy (for instance 1 and 3 if we suggested 3 clusters or 1 and 4 in the case of 4 clusters) have low strengths. The strongest promoters have intermediate energy values (cluster 2 and 2, 3 correspondingly).

Table 2.

Composition of promoter clusters

| Clusters quantity | Cluster number | Forward sequences |

Reverse sequences |

||

| Mean energy of base pair interaction (kJ/mol) | Mean strength | Mean energy of base pair interaction (kJ/mol) | Mean strength | ||

| 3 | 1 | 44.1±0.45 | 0.75±0.09 | 46.4±0.48 | 0.38±0.05 |

| 2 | 53.5±0.56 | 0.95±0.08 | 47.2±0.68 | 2.16±0.11 | |

| 3 | 49.3±0.37 | 2.90±0.10 | 51.2±0.55 | 1.03±0.10 | |

| 4 | 1 | 44.1±0.45 | 0.75±0.09 | 45.4±0.76 | 0.37±0.04 |

| 2 | 52.6±0.44 | 1.01±0.08 | 47.2±0.68 | 2.16±0.11 | |

| 3 | 49.3±0.37 | 2.90±0.10 | 49.4±0.32 | 1.10±0.06 | |

| 4 | 58.0±0.00 | 0.71±0.01 | 55.4±0.27 | 0.99±0.15 | |

It has long been known that DNA must be locally melted in order to be transcribed (Spassky et al., 1985). Most transcription regulators act at the steps leading up to DNA melting (Gralla, 1996). The base-specific interaction between defined segments of DNA and the σ 70 subunit of the RNAP leads to separation of base pairs (primarily nontemplate strand bases in the −10 promoter region) and exposure of the template strand for RNA synthesis (Roberts and Roberts, 1996). A short segment is melted to make the template strand accessible to the catalytic core (Gourse et al., 2000). In this process holoenzyme first binds to the promoter to form a closed complex and then opens a segment roughly from position −11 to +3 (Kainz and Roberts, 1992). The sequences on the nontemplate strand of the −10 consensus element, which extends from −12 to −7, are known to have important influence (Roberts and Roberts, 1996). Both the sigma and core components of RNAP may take part in the melting reaction. Mutations of RNAP subunits can affect promoter melting (Jones et al., 1992; Juang and Helmann, 1994). This α subunit of RNAP binds to upstream element DNA using minor groove as well as backbone contacts. The functional groups in the −10 and −35 hexamers are involved in the interaction with the σ subunit (Ross et al., 2001).

Our own results indicated that energy of base pairs interaction in promoter sequences is significantly decreased in the region between −45 and +7 (Fig.2). This phenomenon is connected with elevated AT-contents in this area (Fig.3). The decreased energy of pairs interaction leads to easier melting of these regions. Visualization of these data makes clearer the physical bases of different functional roles of different promoter regions. The validity of these differences is proved by data of Fig.3, where the t-criterion of differences of random sequences is presented. The mean base pair energy per promoter sequence differs between promoters.

This indicates that conformational changes in the DNA that accompany initiation of transcription such as promoter melting are determined by the polymerase rather than the DNA sequence (Meier et al., 1995).

CONCLUSION

The process of transcription is regulated in a very complex manner. But in spite of this we suppose that on the general level of promoter structure it may be revealed that some simple laws that involved in gene regulation. This work attempts to find simple general laws to explain differences in promoter strengths. We elaborated the graphic method for presentation of the energy properties of promoter sequences. Our data indicate that energy distribution throughout the promoter sequence is minimal at −35, −8 and +7 (Fig.2). The obtained results do not depend on promoter orientation in the genome and are similar for forward and reverse sequences. In our opinion this energy distribution is caused by the necessity of specific interaction between regulatory proteins and promoter sequences. The most important difference from the random sequences area is related to −8 (Fig.2) that is caused by the excess of AT-pairs in this region (Fig.3). We revealed several groups of promoters and their energy properties. These data indicate that the energy differences between clusters do not directly correspond to differences in their strengths. The promoters in clusters with minimal and maximal energy have low strengths, and the strongest promoters correspond to other clusters characterized by intermediate mean energy values.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very indebted to Dr. H. Kiryu for data concerning promoter strengths and very useful information.

References

- 1.Babb K, McAlister JD, Miller JC, Stevenson B. Molecular characterization of borrelia burgdorferi promoter/operator elements. Journal of Bacteriology. 2004;186(9):2745–2756. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.9.2745-2756.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burr T, Mitchell J, Minchin S, Busby S. DNA sequence elements located immediately upstream of the −10 hexamer in Escherichia coli promoters: a systematic study. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1864–1870. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.9.1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell EA, Muzzin O, Chlenov M, Sun JL, Olson CA, Weinman O, Trester-Zedlitz ML, Darst SA. Structure of the bacterial RNA polymerase promoter specificity σ subunit. Mol Cell. 2002;9:527–539. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gourse RL, Ross W, Gaal T. UPs and downs in bacterial transcription initiation: role of the α subunit of RNA polymerase in promoter recognition. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:687–695. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gralla JD. Activation and repression of E. coli promoters. Curr Opin Genet. 1996;6(5):526–530. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(96)80079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo Y, Gralla JD. Promoter opening via a DNA fork junction binding activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(20):11655–11660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones CH, Tatti KM, Moran CPJr. Effects of amino acid substitutions in the −10 binding region of sigma E from Bacillus subtilis . J Bacteriol. 1992;174(2):6815–6821. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.21.6815-6821.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juang YL, Helmann JD. A promoter melting region in the primary sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis. Identification of functionally important aromatic amino acids. J Mol Biol. 1994;235(5):1470–1488. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kainz M, Roberts J. Structure of transcription elongation complexes in vivo. Science. 1992;255:838–841. doi: 10.1126/science.1536008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kajitani M, Ishihama A. Determination of the promoter strength in the mixed transcription system. II. Promoters of ribosomal RNA, ribosomal protein S1 and recA protein operons from Escherichia coli . Nucleic Acids Research. 1983;11(12):3873–3888. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.12.3873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Kawashima S, Kuno Y, Hattori M. The KEGG resources for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D277–D280. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kudritskaya ZG, Danilov VI. Quantum mechanical study of bases interactions in various associates in atomic dipole approximation. J Theor Biol. 1976;59:301–318. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(76)90172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meier T, Schickor P, Wedel A, Cellai L, Heumann H. In vitro transcription close to the melting point of DNA: analysis of Thermotoga maritima RNA polymerase-promoter complexes at 75 degrees C using chemical probes. Nucleic Acids Research. 1995;23(6):988–994. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.6.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mori H, Isono K, Horiuchi T, Miki T. Functional genomics of Escherichia coli in Japan. Res Microbiol. 2000;151:121–128. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(00)00119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murakami KS, Masuda S, Campbell EA, Muzzin O, Darst SA. Structural basis of transcription initiation: an RNA polymerase holoenzyme-DNA complex. Science. 2002;296:1285–1290. doi: 10.1126/science.1069595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts CW, Roberts JW. Base-specific recognition of the nontemplate strand of promoter DNA by E. coli RNA polymerase. Cell. 1996;86(3):495–501. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross W, Ernst A, Gourse RL. Fine structure of E. coli RNA polymerase-promoter interactions: α subunit binding to the UP element minor groove. Genes and Development. 2001;15(5):491–506. doi: 10.1101/gad.870001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spassky A, Kirkegaard K, Buc H. Changes in the DNA structure of the lac UV5 promoter during formation of an open complex with Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Biochemistry. 1985;24(11):2723–2731. doi: 10.1021/bi00332a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogel SK, Schulz A, Rippe K. Binding affinity of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase σ 54 holoenzyme for the glnAp2, nifH and nifL promoters. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30(18):4094–4101. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]