Abstract

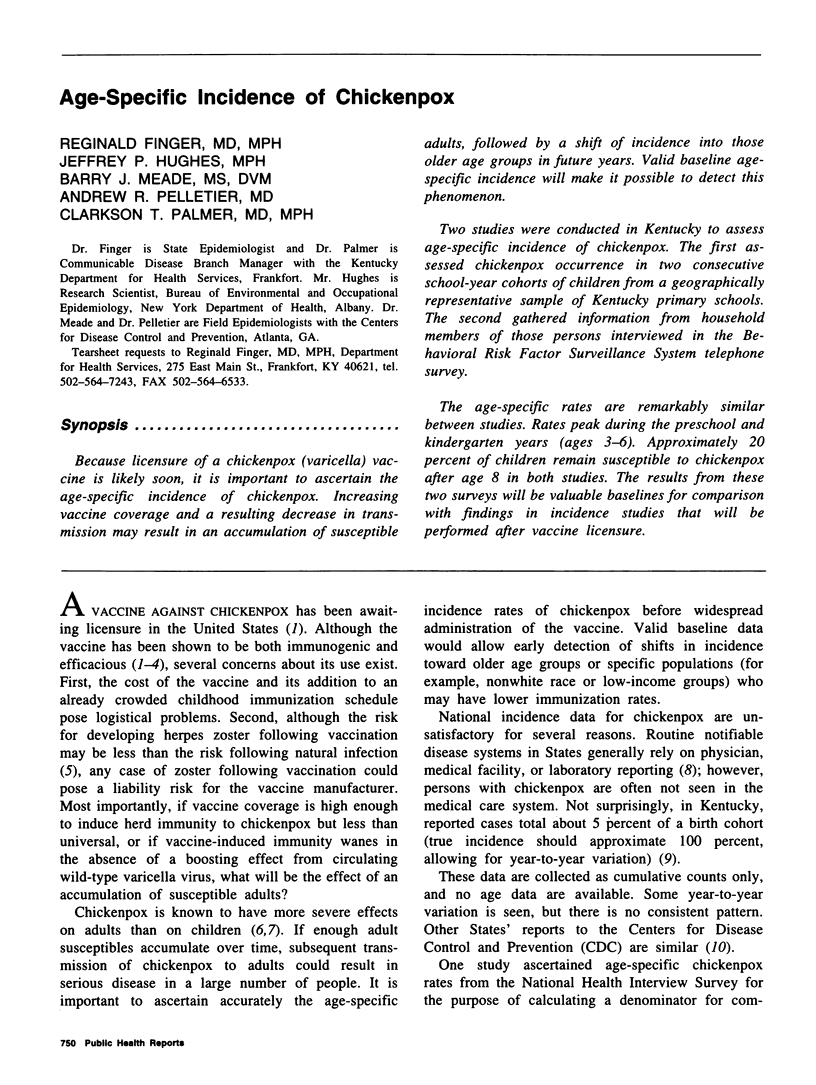

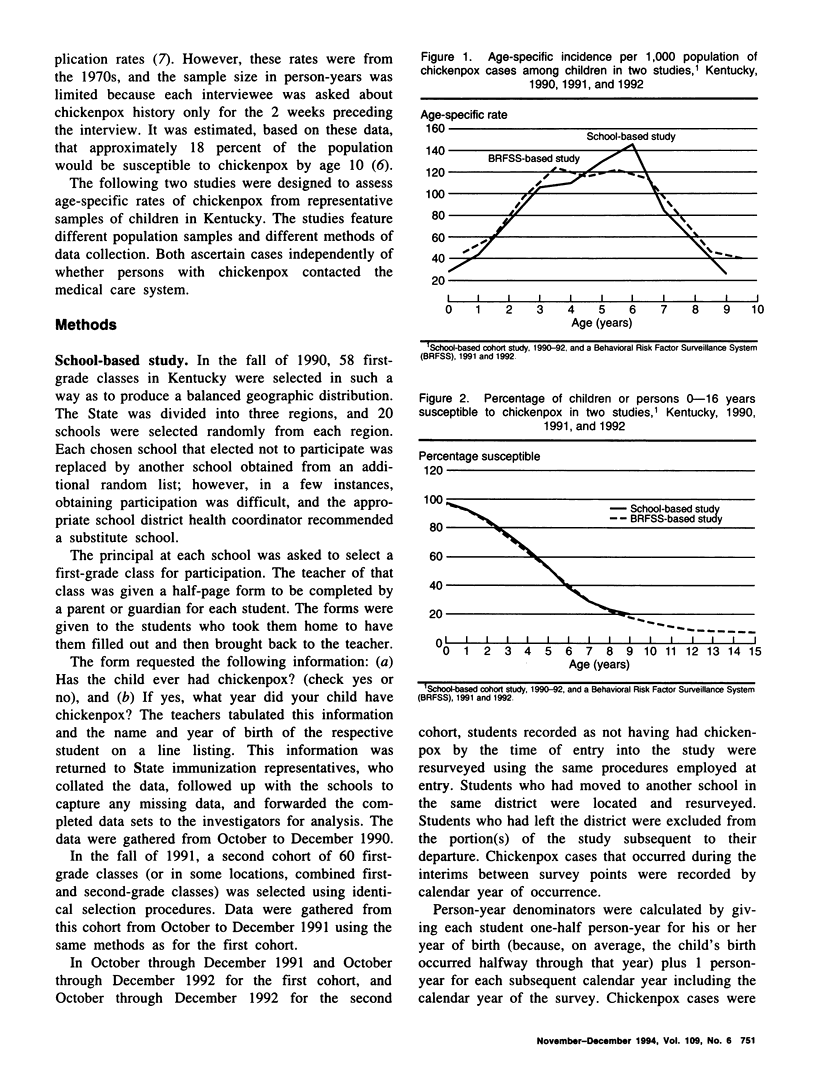

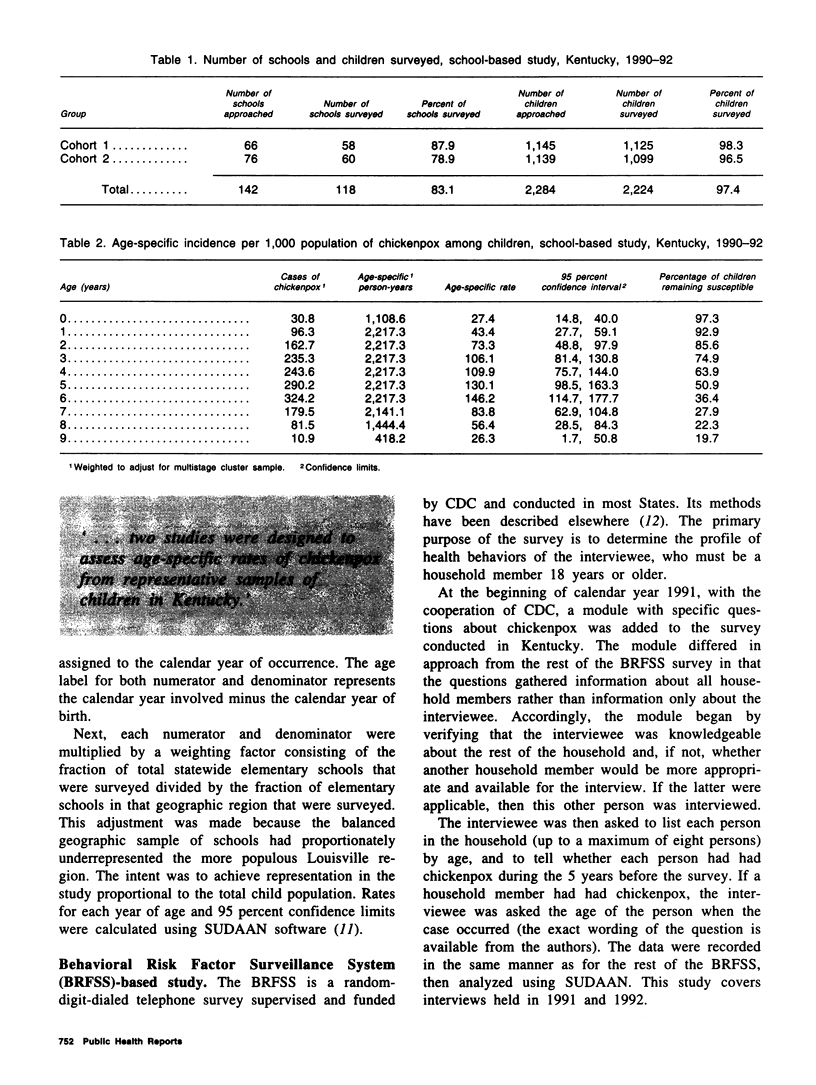

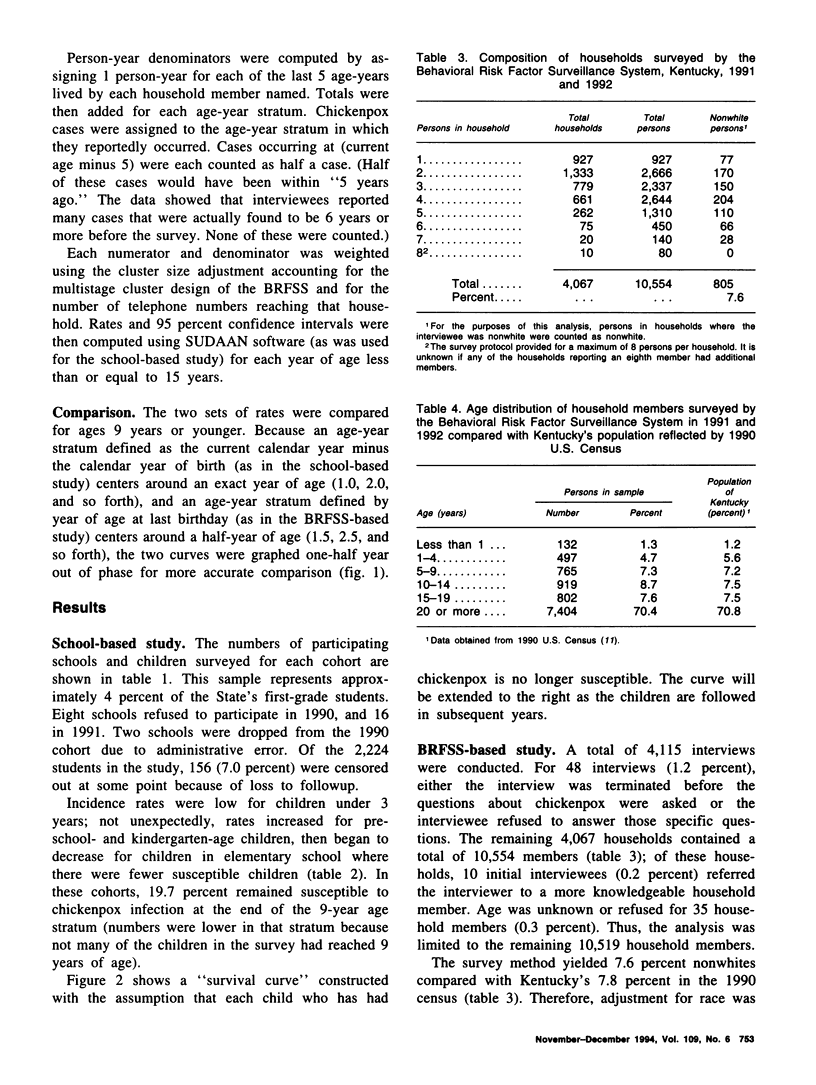

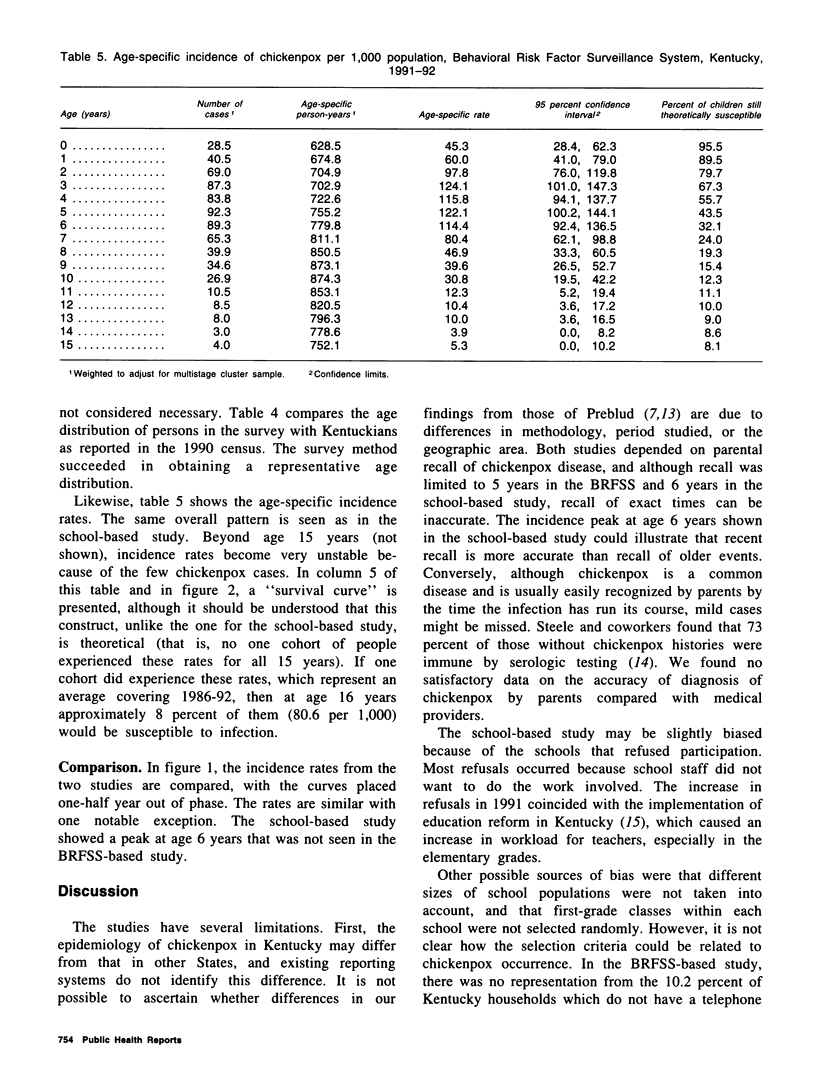

Because licensure of a chickenpox (varicella) vaccine is likely soon, it is important to ascertain the age-specific incidence of chickenpox. Increasing vaccine coverage and a resulting decrease in transmission may result in an accumulation of susceptible adults, followed by a shift of incidence into those older age groups in future years. Valid baseline age-specific incidence will make it possible to detect this phenomenon. Two studies were conducted in Kentucky to assess age-specific incidence of chickenpox. The first assessed chickenpox occurrence in two consecutive school-year cohorts of children from a geographically representative sample of Kentucky primary schools. The second gathered information from household members of those persons interviewed in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System telephone survey. The age-specific rates are remarkably similar between studies. Rates peak during the preschool and kindergarten years (ages 3-6). Approximately 20 percent of children remain susceptible to chickenpox after age 8 in both studies. The results from these two surveys will be valuable baselines for comparison with findings in incidence studies that will be performed after vaccine licensure.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chorba T. L., Berkelman R. L., Safford S. K., Gibbs N. P., Hull H. F. Mandatory reporting of infectious diseases by clinicians. JAMA. 1989 Dec 1;262(21):3018–3026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon A. A., Steinberg S. P., Gelb L. Live attenuated varicella vaccine use in immunocompromised children and adults. Pediatrics. 1986 Oct;78(4 Pt 2):757–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guess H. A., Broughton D. D., Melton L. J., 3rd, Kurland L. T. Population-based studies of varicella complications. Pediatrics. 1986 Oct;78(4 Pt 2):723–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa T., Ihara T., Hattori A., Iwasa T., Kamiya H., Sakurai M., Takahashi M. Application of a live varicella vaccine in children with acute leukemia or other malignant diseases. Pediatrics. 1977 Dec;60(6):805–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence R., Gershon A. A., Holzman R., Steinberg S. P. The risk of zoster after varicella vaccination in children with leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1988 Mar 3;318(9):543–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198803033180904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preblud S. R. Age-specific risks of varicella complications. Pediatrics. 1981 Jul;68(1):14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preblud S. R. Varicella: complications and costs. Pediatrics. 1986 Oct;78(4 Pt 2):728–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remington P. L., Smith M. Y., Williamson D. F., Anda R. F., Gentry E. M., Hogelin G. C. Design, characteristics, and usefulness of state-based behavioral risk factor surveillance: 1981-87. Public Health Rep. 1988 Jul-Aug;103(4):366–375. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele R. W., Coleman M. A., Fiser M., Bradsher R. W. Varicella zoster in hospital personnel: skin test reactivity to monitor susceptibility. Pediatrics. 1982 Oct;70(4):604–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel R. E., Neff B. J., Kuter B. J., Guess H. A., Rothenberger C. A., Fitzgerald A. J., Connor K. A., McLean A. A., Hilleman M. R., Buynak E. B. Live attenuated varicella virus vaccine. Efficacy trial in healthy children. N Engl J Med. 1984 May 31;310(22):1409–1415. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198405313102201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]