Abstract

Objective To evaluate the effectiveness of acupressure in terms of disability, pain scores, and functional status.

Design Randomised controlled trial.

Setting Orthopaedic clinic in Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

Participants 129 patients with chronic low back pain.

Intervention Acupressure or physical therapy for one month.

Main outcome measures Self administered Chinese versions of standard outcome measures for low back pain (primary outcome: Roland and Morris disability questionnaire) at baseline, after treatment, and at six month follow-up.

Results The mean total Roland and Morris disability questionnaire score after treatment was significantly lower in the acupressure group than in the physical therapy group regardless of the difference in absolute score (- 3.8, 95% confidence interval - 5.7 to - 1.9) or mean change from the baseline (- 4.64, - 6.39 to - 2.89). Acupressure conferred an 89% (95% confidence interval 61% to 97%) reduction in significant disability compared with physical therapy. The improvement in disability score in the acupressure group compared with the physical group remained at six month follow-up. Statistically significant differences also occurred between the two groups for all six domains of the core outcome, pain visual scale, and modified Oswestry disability questionnaire after treatment and at six month follow-up.

Conclusions Acupressure was effective in reducing low back pain in terms of disability, pain scores, and functional status. The benefit was sustained for six months.

Introduction

Low back pain is a common health problem worldwide. In addition to conventional physical therapy, acupuncture—classified in group 1 of the complementary and alternative therapies (professionally organised alternative therapies)1—has been shown to be effective in alleviating various types of pain.2 Its efficacy for low back pain remains elusive, however.3 Acupressure, another complementary and alternative therapy, has had increasing attention, as it is manipulated with the fingers instead of needles on the acupoints and has been used for relieving pain, illness, and injuries in traditional Chinese medicine.4

The efficacy of acupressure in relieving pain associated with low back pain has been shown by a randomised controlled trial.5 However, the outcomes in that study were assessed by description of pain character and failed to take into account functional status and disability as recommended by most low back pain researchers.6,7 Although trials have investigated the efficacy of physical therapy, acupuncture, and acupressure in reducing low back pain, the type of outcome measurement has varied from study to study. To establish a standard instrument for comparisons across studies, a standardised “core” set of questions and questionnaires (referred to here as standard outcome measures) has been proposed by an international programme on primary care management of low back pain since 1998.8

We aimed to do a randomised controlled trial using validated Chinese versions of the standard outcome measures to compare the efficacy of acupressure with that of physical therapy in alleviating low back pain and to provide a base for comparison across international studies.

Methods

Study participants

The study took place between 8 January and 12 May 2004, with follow-up until 12 November 2004. We selected 188 participants from among the outpatients of a specialist orthopaedic clinic in Kaoshiung, Taiwan, which offered standardised physical therapy. Patients were eligible if they were aged 18 years and older; they had had chronic low back pain for more than four months, as diagnosed by a senior orthopaedic specialist; their chronic low back pain was not caused by systemic or organic diseases, cancers, or psychiatric diseases; they were not pregnant; they had no acute severe pains needing immediate treatment or surgery; and they had no contraindication to acupressure (that is, no open wound). All participants gave written informed consent.

Sample size determination

We did a pilot trial before the main study to obtain score means and standard deviations with the Roland and Morris disability questionnaire, modified Oswestry disability questionnaire, and visual analogue scale for estimating sample sizes. We took the Roland and Morris disability questionnaire as the primary outcome. To detect the mean difference in score between the two groups (the mean scores in the pilot study were 28.4 (SD 16.9) for the acupressure group and 48.0 (SD 22.9) for the physical therapy group), with a significance level of 5% (two tailed) and statistical power of 80%, we needed 65 participants in each arm.

Randomisation

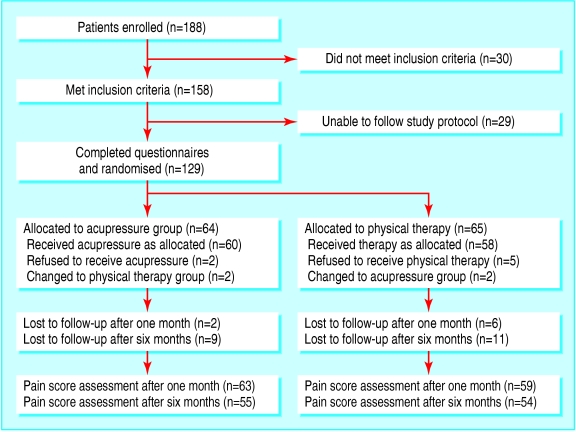

A research assistant independently randomised participants by using a predetermined random table, which was not decoded until the intervention was assigned. After exclusion of ineligible patients, 129 (69%) patients aged between 18 and 81 met our eligibility and were randomly allocated to two arms: 64 patients in the acupressure group and 65 patients in the physical therapy group.

Interventions

Each participant received six sessions within one month. One senior acupressure therapist gave each session of acupressure treatment to ensure a uniform technique and consistent experience. The participants in the physical therapy group received the routine physical therapy offered by the orthopaedic specialist clinic, including pelvic manual traction, spinal manipulation, thermotherapy, infrared light therapy, electrical stimulation, and exercise therapy, as decided by the physical therapist.

Blinding

Blinded treatment of acupressure is impractical. To reduce the “Hawthorne effect” (whereby patients with known higher pain scores receive more effort from the therapist), both the acupressure therapist and the physical therapists were blind to pretreatment assessment. We asked patients, without referring to the pretreatment assessment, to assess the post-treatment pain scores and ratings by filling out the questionnaires or by telephone interview immediately after completing six treatment sessions or the one month period, whichever came first. The research assistant who did the post-treatment and six month follow-up interviews by telephone was also blind to pretreatment assessment and was told beforehand not to ask the participants about the details of the intervention in order to remain blind to the intervention as far as possible. In addition, to avoid observation bias, the assessor was blind to intervention group before analysis of data was complete.

Outcome measurements

Although the Chinese versions of the standard outcome measures comprise four components—core outcome measures, Roland and Morris disability questionnaire, Oswestry disability questionnaire, and EuroQoL—we used only the first three, because the patients in the pilot study found EuroQoL difficult to use. We also used a visual analogue scale for recording pain scores. We asked participants in each group to provide baseline information, including date of birth, sex, marital status, occupation category, educational level, and sleeping quality, and to complete the Chinese version of the standard outcome measures at enrolment. We used separate sets of questionnaires for pretreatment, post-treatment, and six month follow-up assessments by patients and research assistant. To avoid recall bias, only the reference number and participant's name were shown on these questionnaires, without revealing the previous assessment. We took Roland and Morris disability questionnaire as the primary outcome and the other measures as secondary outcomes.

When evaluating the treatment efficacy, we divided the total scores measured by the Roland and Morris disability questionnaire into two score scales for measuring the degree of disability, taking 0-12 as minimal disability and 13-24 as significant disability. We used the modified version of the Oswestry disability questionnaire used in the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons lumbar cluster, which has nine questions with six ratings. We summed ratings on each item as total scores for each patient. We divided the total scores into five grades for measuring the degree of disability, taking 0-11 as minimal disability, 12-22 as moderate disability, 23-32 as severe disability, 33-43 as crippled, and 3 44 as bed bound.

Statistical analysis

For comparisons of baseline variables, we used Student's t test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. Analysis was by intention to treat. For participants lost to follow-up, we conservatively assumed that the values at the post-treatment and six month follow-up assessments were identical to those at baseline.

As Roland and Morris disability questionnaire score is a skewed, non-normal distribution, we used the Wilcoxon rank sum test to assess the difference between the two groups.9 We used the non-parametric jack-knife method to calculate 95% confidence intervals.10 We used analysis of covariance to assess the differences and 95% confidence intervals between the two groups in visual analogue scale pain scores and pain scores measured by the core outcome measures and Oswestry disability questionnaire, with adjustment for pretreatment score alone or together with other possible baseline variables such as duration of low back pain.9 We used logistic regression models to estimate the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of having significant disability as measured by the Roland and Morris disability questionnaire, with adjustment for pretreatment score alone or together with other possible baseline variables. We applied cumulative logit models to the ordinal property of disability defined by Oswestry disability questionnaire to estimate incremental odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.11 We used SAS version 9 for statistical analyses.

Results

The figure shows a summary of enrolment, randomisation, loss to follow-up, and assessment. Two participants in the acupressure group and five in the physical therapy group refused to receive the designated intervention. Two participants in each group switched to receive the treatment of the opposite group. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics in the two treatment groups; no differences existed in demographic, educational, or occupational aspects.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by treatment group. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Variable | Acupressure (n=64) | Physical therapy (n=65) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 50.2 (13.8) | 52.6 (17.2) |

| Male sex | 21 (33) | 17 (26) |

| Marital status: | ||

| Single | 10 (16) | 11 (17) |

| Married | 54 (84) | 54 (83) |

| Education: | ||

| College and above | 17 (27) | 14 (21) |

| Senior high school | 20 (31) | 16 (25) |

| Junior high school or below | 27 (42) | 35 (54) |

| Occupation: | ||

| Household keeper | 18 (28) | 16 (25) |

| Office worker | 17 (27) | 8 (12) |

| Heaver labour | 9 (14) | 8 (12) |

| Other | 20 (31) | 33 (51) |

| Median (range) time since onset of pain (years) | 3.3 (0.2-33.3) | 1.6 (0.2-34.3) |

| Median (range) length of latest pain period (months) | 14.5 (0.02-360) | 12 (0.25-432) |

Roland and Morris disability questionnaire

The mean total Roland and Morris disability questionnaire score after treatment was significantly lower in the acupressure group than in the physical therapy group, regardless of the difference in absolute score (- 3.8, 95% confidence interval - 5.7 to - 1.9) or mean change from baseline (- 4.64, - 6.39 to - 2.89) (table 2). Acupressure conferred an 89% (95% confidence interval 61% to 97%) reduction in significant disability compared with physical therapy after adjustment for degree of disability at baseline. The mean difference in total score between the two groups after treatment remained statistically significant (P < 0.05) after adjustment for pretreatment score or disability together with other baseline characteristics shown in table 1.

Table 2.

Roland and Morris disability questionnaire (RMDQ) scores pretreatment, post-treatment, and at six month follow-up

| Sums of RMDQ scores/ordinal scorings (0-24) | Acupressure (n=64) | Physical therapy (n=65) | Comparison 1† | Comparison 2‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment | ||||

| Mean (SD) total score | 10.9 (6.2) | 10.0 (5.3) | — | — |

| Degree of disability (No): | ||||

| Minimal (0-12) | 36 | 45 | — | — |

| Significant (13-24) | 28 | 20 | ||

| Post-treatment | ||||

| Mean (SD) total score | 5.4 (5.0) | 9.2 (5.8) | −3.8*** (−5.7 to −1.9) | −4.64*** (−6.39 to −2.89) |

| Degree of disability (No): | ||||

| Minimal (0-12) | 56 | 46 | OR=0.11** | — |

| Significant (13-24) | 8 | 19 | (0.03 to 0.39) | |

| Six month follow-up | ||||

| Mean (SD) total score | 2.2 (3.2) | 6.7 (5.5) | −4.5*** (−6.1 to −2.9) | −5.36*** (−7.21 to −3.52) |

| Degree of disability (No): | ||||

| Minimal (0-12) | 63 | 57 | OR=0.07* | — |

| Significant (13-24) | 1 | 8 | (0.01 to 0.57) |

Absolute difference between groups analysed by Wilcoxon rank sum test for total scores, 95% confidence interval calculated by non-parametric jack-knife method; odds ratio (OR) (95% confidence interval) of showing significant degree of disability for acupressure compared with physical therapy, analysed by multiple logistic regression.

Difference (95% confidence interval) in mean change in score from baseline.

P<0.05.

P<0.01.

P<0.0001.

Given the difference in rate of significant disability (table 2), the estimated number needed to be treated with acupressure to reduce cases with severe disability by one was 5.98. As seen in table 2, the improvement in Roland and Morris disability questionnaire score in the acupressure group compared with the physical group still remained at the six month follow-up. The number needed to treat with acupressure was 9.31.

Core outcome measures and visual analogue scale

After adjustment for pretreatment score (comparison 1 in table 3), the differences in mean scores for core outcome measures in the acupressure group were significantly different from those in the physical therapy group. Mean scores were lower in the acupressure group for the items “low back pain,” “leg pain,” “pain interferes with normal work,” “days cut down on doing things,” and “days off from work/school.” Mean scores were higher in the acupressure group for the items “satisfaction of life with the symptoms” and “satisfaction with previous treatment.” The mean scores for the pain visual scale and sleeping with low back pain were lower in the acupressure group than in the physical therapy group. The differences between the two groups remained statistically significant (P < 0.05) after adjustment for pretreatment score and other baseline characteristics. In terms of mean change from baseline, the benefit was also greater in the acupressure group for all variables (comparison 2 in table 3). The statistically significant improvement remained or even increased at the six month follow-up (table 3).

Table 3.

Mean (SD) core outcome measures pretreatment, post-treatment, and at six month follow-up

|

Pre-treatment

|

Post-treatment

|

Six month follow-up

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core outcome measures and related indicators | Acupressure (n=64) | Physical therapy (n=65) | Acupressure (n=64) | Physical therapy (n=65) | Comparison 1† | Comparison 2‡ | Acupressure (n=64) | Physical therapy (n=65) | Comparison 1† | Comparison 2‡ |

| Degree of “how bothersome”: | ||||||||||

| Low back pain | 2.97 (1.01) | 2.78 (0.96) | 2.11 (0.86) | 2.57 (0.83) | −0.53*** (−0.80 to −0.28) | −0.64*** (−0.97 to −0.32) | 1.59 (0.73) | 2.17 (0.89) | −0.62*** (−0.90 to −0.35) | −0.76*** (−1.13 to −0.39) |

| Leg pain | 2.78 (1.16) | 2.74 (1.11) | 1.94 (0.85) | 2.52 (0.97) | −0.60*** (−0.87 to −0.34) | −0.63** (−0.97 to −0.29) | 1.48 (0.71) | 2.15 (0.97) | −0.68*** (−0.96 to −0.41) | −0.71** (−1.10 to −0.32) |

| Pain interferes with normal work | 2.78 (1.11) | 2.45 (0.98) | 2.05 (0.88) | 2.38 (1.01) | −0.50** (−0.78 to −0.21) | −0.67** (−1.02 to −0.33) | 1.61 (0.75) | 2.23 (0.88) | −0.70*** (−0.98 to −0.42) | −0.96*** (−1.35 to −0.57) |

| Satisfaction of life with symptoms | 1.39 (0.68) | 1.57 (0.66) | 2.38 (1.27) | 1.97 (1.04) | 0.46* (0.05 to 0.86) | 0.58** (0.15 to 1.02) | 3.63 (1.16) | 2.95 (1.24) | 0.69** (0.27 to 1.11) | 0.85** (0.38 to 1.32) |

| Days cut down on doing things | 5.0 (10.5) | 3.4 (8.6) | 1.6 (4.7) | 4.0 (9.8) | −3.16** (−5.38 to −0.93) | −3.99** (−6.83 to −1.15) | 0.4 (2.6) | 2.6 (8.0) | −2.48* (−4.5 to −0.50) | −3.70* (−6.98 to −0.42) |

| Days off from work/school | 4.2 (9.5) | 3.3 (8.6) | 1.5 (5.4) | 3.5 (9.3) | −2.45* (−4.59 to −0.31) | −2.87* (−5.51 to −0.23) | 0.6 (3.8) | 2.5 (8.0) | −2.15* (−4.22 to −0.09) | −2.79 (−5.94 to −0.35) |

| Satisfaction with previous treatment | 2.06 (1.39) | 2.13 (1.68) | 4.12 (1.22) | 3.06 (1.38) | 1.25*** (0.82 to 1.68) | 1.68*** (1.17 to 2.20) | 4.39 (0.75) | 3.15 (1.14) | 1.39*** (1.02 to 1.76) | 1.83*** (1.37 to 2.29) |

| Pain visual scale (0 to 100) | 58.8 (17.88) | 57 (17.83) | 30.6 (21.75) | 48.0 (23.4) | −18.38*** (−25.60 to −11.17) | −19.27*** (−27.04 to −11.5) | 16.1 (17.4) | 41.4 (24.6) | −25.92*** (−33.06 to −18.77) | −27.12*** (−35.3 to −18.94) |

| Sleeping with low back pain | 2.17 (0.86) | 2.03 (0.97) | 1.44 (0.59) | 1.85 (0.85) | −0.46*** (−0.69 to −0.24) | −0.55** (−0.84 to −0.26) | 1.16 (0.44) | 1.72 (0.84) | −0.61*** (−0.82 to −0.39) | −0.71*** (−1.02 to −0.39) |

Absolute difference (95% confidence interval) between groups by analysis of covariance.

Difference (95% confidence interval) in mean change in core outcome measures from baseline.

P<0.05.

P<0.01.

P<0.0001.

Modified Oswestry disability questionnaire

The mean total Oswestry disability questionnaire score after treatment was significantly lower in the acupressure group than in the physical therapy group, regardless of the difference in absolute score (- 5.34, - 7.62 to - 3.05) or mean change from baseline (- 6.81, - 9.49 to - 4.12) (table 4). As regards disability classified by five grades, the odds ratio of increasing one grade of disability was 0.22 (95% confidence interval 0.11 to 0.48; P = 0.0001) for the acupressure group. The differences between the two groups remained significant (P < 0.05) after adjustment for pretreatment score or disability in conjunction with other baseline characteristics.

Table 4.

Modified Oswestry disability questionnaire (ODQ) scores pretreatment, post-treatment, and at six month follow-up

| Sums of ODQ scores/ordinal scorings (0-54) | Acupressure (n=64) | Physical therapy (n=65) | Comparison 1† | Comparison 2‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment | ||||

| Mean (SD) total score | 24.4 (10.0) | 21.1 (8.7) | ||

| Degree of disability (No): | ||||

| Minimal (0-11) | 4 | 3 | ||

| Moderate (12-22) | 29 | 42 | ||

| Severe (23-32) | 14 | 13 | ||

| Crippled (33-43) | 15 | 5 | ||

| Bed bound (≥44) | 2 | 2 | ||

| Post-treatment | ||||

| Mean (SD) total score | 17.0 (7.6) | 20.6 (8.8) | −5.34*** (−7.62 to −3.05) | −6.81*** (−9.49 to −4.12) |

| Degree of disability (No): | ||||

| Minimal (0-11) | 17 | 7 | OR=0.22** (0.11 to 0.48) | |

| Moderate (12-22) | 32 | 37 | ||

| Severe (23-32) | 12 | 15 | ||

| Crippled (33-43) | 3 | 4 | ||

| Bed bound (≥44) | 0 | 2 | ||

| Six month follow-up | ||||

| Mean (SD) total score | 12.2 (4.9) | 17.9 (8.1) | −6.03*** (−8.22 to −3.84) | −7.99*** (−10.8 to −5.17) |

| Degree of disability (No): | ||||

| Minimal (0-11) | 39 | 17 | OR=0.11*** (0.04 to 0.27) | |

| Moderate (12-22) | 22 | 33 | ||

| Severe (23-32) | 2 | 11 | ||

| Crippled (33-43) | 0 | 3 | ||

| Bed bound (≥44) | 0 | 0 |

Absolute difference (95% confidence interval) between groups by analysis of covariance.

Difference (95% confidence interval) in mean change in core outcome measures from baseline.

P<0.01.

P<0.0001.

Given the difference in rate of significant disability between the two groups (table 4), the estimated number needed to treat with acupressure to reduce the degree of disability by one grade was 6.15. As seen in table 4, the improvement in Oswestry disability questionnaire score in the acupressure group compared with the physical group remained at the six month follow-up. The number needed to treat with acupressure was 4.58.

Figure 1.

Trial profile

Discussion

This study shows that acupressure is more efficacious in alleviating low back pain than is physical therapy, as measured by pain visual analogue scale, core outcome measures, Roland and Morris disability questionnaire, and Oswestry disability questionnaire. The results support the conclusion of the previous randomised controlled clinical trial on low back pain treated by acupressure.5 Acupressure may thus be useful for reducing pain and improving body function and level of disability in low back pain.

Outcome measures used

Most of the domains of the core outcome measures were able to distinguish the difference between the acupressure group and the physical therapy group, irrespective of absolute change or mean change from baseline at post-treatment and six month follow-up assessments. The Roland and Morris disability questionnaire has been considered an outcome measure sensitive to changes in clinical status for the study of low back pain.12,13 In our study, we saw statistically significant treatment differences with this questionnaire. Results for the Oswestry disability questionnaire score also showed functional improvement with acupressure irrespective of whether the score was classified into five ordinal categories or modified by a simple summation scoring method.14

The World Health Organization recommended that the visual analogue scale should be included as an outcome measure in all studies on low back pain,15 so we included this measure in the study. Sleep disturbance is a common complaint of patients with low back pain, and we included it as a reference indicator; it showed a significant difference between the two groups in absolute change and mean change from baseline at the posttreatment and six month follow-up assessments.

Limitations of the study

Three concerns about the study should be clarified. Firstly, the efficacy of acupressure in pain relief might be attributed to a psychological effect emerging between patients and therapist during therapy. However, we believe that such a confounding effect caused by interaction or a doctor-patient relationship is unlikely to affect the results, because people who seek physical therapy generally have a strong desire for orthodox/Western medicine, the therapists in both groups were blind to the results of pretreatment assessments, and the use of Roland and Morris disability questionnaire and Oswestry disability questionnaire was mainly to assess functional status and disability, which should be less affected by the psychological effect than subjective measures of pain.

Secondly, 20 (15.5%) patients were lost to follow-up at six months. We do not believe that this would have had much influence on the result. However, the problem might be ameliorated by using an intention to treat method that included patients lost to follow-up in the analysis. As mentioned before, we substituted missing data for patients lost to follow-up with baseline or posttreatment data by assuming no change since last contact.

Finally, the effectiveness of any manipulation therapy is highly dependent on the therapist's technique and experience. The selection of treatment modality and technique to be applied to patients depended on the discretion of the therapist for both physical therapy and acupressure, even though standardised procedures were established. Ensuring comparability between treatments is therefore important. For physical therapy, this should not be a serious problem because the technique has been well established in orthodox/Western medicine. We avoided variation across practitioners for acupressure by using only one therapist. The use of a single therapist may enhance internal validity but also imposes a threat to external validity. We hope that this technique can be imparted to other therapists now that its efficacy has been shown in our study, so that acupressure can be used in other populations. How acupressure can be generalised to patients with low back pain is the subject of ongoing research.

What is already known on this topic

Acupressure is efficacious in alleviating low back pain in terms of pain character description

Little is known about its efficacy in reducing low back pain assessed with standard outcome measures

What this study adds

Acupressure was effective in reducing low back pain in terms of pain scores, functional status, and disability

The effect was not only seen in the short term but lasted for six months

Conclusions

This randomised controlled clinical trial has shown the efficacy of acupressure compared with physical therapy in pain relief for patients with low back pain in terms of disability, pain scores, and functional status. The results provide a base for comparison across international studies.

Ethical approval: The study protocol was approved by an ethics committee of the specialist orthopaedic clinic.

We thank Richard A Deyo for granting permission to use the standardised “core” set of questions and questionnaires.

Contributors: TH-HC was responsible for study design and implementation, data collection and analysis, and interpretation of the findings and drafted the paper. LL-CH, C-HK, and LHL contributed to study implementation, data collection, interpretation of findings, and writing the draft. AM-FY and K-LC contributed to management and analysis, interpretation of findings, and revision of the manuscript. TH-HC and LL-CH are guarantors.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Mills SY. Regulation in complementary and alternative medicine. BMJ 2001;322: 158-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA 1998;280: 1569-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ernst E, White AR. Acupuncture for low back pain: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 1998;158: 2235-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hesketh T, Zhu WX. Health in China: Traditional Chinese medicine: one country, two systems. BMJ 1997;315: 115-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsieh LL, Kuo CH, Yen MF, Chen THH. A randomized controlled clinical trial for low back pain treated by acupressure and physical therapy. Prev Med 2004;39: 168-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris disability questionnaire and the Oswestry disability questionnaire. Spine 2000;25: 3115-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melzack R, Torgerson WS. On the language of pain. Anesthesiology 1971;34: 50-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deyo RA, Battie M, Beurskens AJ, Bombardier C, Croft P, Koes B, et al. Outcome measures for low back pain research: a proposal for standardized use. Spine 1998;23: 2003-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman and Hall, 1991.

- 10.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. London: Chapman and Hall, 1993.

- 11.McCullagh P. Regression models for ordinal data (with discussion). J Royal Stat Soc B 1980;42: 109-42. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzukamo Y, Fukuhara S, Kikuchi S, Konno S, Roland M, Iwamoto Y, et al. Validation of the Japanese version of the Roland-Morris disability questionnaire. J Orthop Sci 2003;8: 543-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coste J, Le Parc JM, Berge E, Delecoeuillerie G, Paolaggi JB. [French validation of a disability rating scale for the evaluation of low back pain (EIFEL questionnaire).] Rev Rhum Ed Fr 1993;60: 335-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flynn TW, Fritz JM, Wainner RS, Whitman JM. The audible pop is not necessary for successful spinal high-velocity thrust manipulation in individuals with low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84: 1057-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehrlich G, Khaltaev NG. Low back pain initiative. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1999.