Abstract

The Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin is an 88-kDa secreted protein that causes multiple alterations in mammalian cells and is considered an important virulence factor in the pathogenesis of peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer. We have shown previously that a VacA mutant protein lacking amino acids 6 to 27 (Δ6-27p88 VacA) is able to inhibit many activities of wild-type VacA in a dominant-negative manner. Analysis of a panel of C-terminally truncated Δ6-27p88 VacA proteins indicated that a fragment containing amino acids 1 to 478 (Δ6-27p48) exhibited a dominant-negative phenotype similar to that of the full-length Δ6-27p88 VacA protein. In contrast, a shorter VacA fragment lacking amino acids 6 to 27 (Δ6-27p33) did not exhibit detectable inhibitory activity. The Δ6-27p48 protein physically interacted with wild-type p88 VacA, whereas the Δ6-27p33 protein did not. Mutational analysis indicated that amino acids 351 to 360 are required for VacA protein-protein interactions and for dominant-negative inhibitory activity. The C-terminal portion (p55 domain) of wild-type p88 VacA could complement either Δ6-27p33 or Δ(6-27/351-360)p48, reconstituting dominant-negative inhibitory activity. Collectively, our data provide strong evidence that the inhibitory properties of dominant-negative VacA mutant proteins are dependent on interactions between the mutant VacA proteins and wild-type VacA, and they allow mapping of a domain involved in the formation of oligomeric VacA complexes.

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium that chronically infects the stomachs of >50% of the human population and is a major risk factor for the development of peptic ulcer disease, distal gastric adenocarcinoma, and gastric lymphoma (13, 37). Most H. pylori strains secrete an 88-kDa vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA) (5, 21), which is considered an important virulence factor in the pathogenesis of these diseases (2, 4, 15, 40). The most prominent effect of VacA is its capacity to induce extensive cell vacuolation in epithelial cells in vitro (5, 21). VacA can also have a variety of other cellular effects, including depolarization of the membrane potential (27, 34, 39), alteration of mitochondrial membrane permeability (45, 46), apoptosis (7, 46), detachment of epithelial cells from the basement membrane (16), interference with the process of antigen presentation (29), activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (3, 31), and inhibition of activation-induced proliferation of T lymphocytes (3, 19, 38). Many of these effects are dependent on the capacity of VacA to form anion-selective membrane channels (10, 11, 27, 38, 39, 43, 45, 46).

VacA is translated as a 140-kDa protoxin that undergoes amino- and carboxyl-terminal cleavage during the secretion process, yielding a mature 88-kDa secreted VacA toxin (5, 9, 32, 33, 40). The mature secreted 88-kDa VacA protein can undergo further proteolytic degradation into two fragments that are about 33 kDa and 55 kDa in mass, designated p33 and p55, respectively (6, 32, 40, 42). The p33 and p55 VacA fragments may represent two distinct subunits or domains of VacA (41, 42, 48). VacA can assemble into large flower-shaped structures comprised of 6 to 14 88-kDa monomers (1, 6, 14, 23). This ability of VacA to assemble into oligomeric structures is thought to be required for membrane channel formation and vacuolating cytotoxicity (41-43, 47, 48).

Several VacA mutant proteins that lack vacuolating cytotoxic activity have been described (26, 27, 43, 48, 49). One such mutant, a VacA protein with a deletion of amino acids 6 to 27 (hereafter termed Δ6-27p88), is of particular interest because of its capacity to inhibit the activities of wild-type VacA in a dominant-negative manner. When mixed with wild-type VacA, Δ6-27p88 potently inhibits the abilities of wild-type VacA to cause cell vacuolation (25, 26, 43), induce apoptosis (7, 46), and inhibit activation-induced proliferation of T lymphocytes (38). The mechanism by which Δ6-27p88 exhibits a dominant-negative phenotype is not completely understood, but it is thought to involve the formation of mixed oligomeric structures composed of both wild-type and mutant VacA proteins (25, 43). A detailed analysis of the structural features of Δ6-27p88 required for the dominant-negative phenotype has not yet been reported. In this study, we describe the mapping of a minimum VacA domain that exhibits a dominant-negative phenotype. Our data indicate that a VacA fragment corresponding to the first 478 amino acids of VacA (Δ6-27p48) can physically interact with wild-type VacA and inhibit the vacuolating cytotoxic activity of wild-type VacA in a dominant-negative manner. In addition, we present evidence indicating that the inhibitory properties of dominant-negative VacA mutant proteins are dependent on the ability of these proteins to form mixed oligomeric complexes with wild-type VacA. Finally, we identify a specific region of VacA (i.e., amino acids 351 to 360) that is required for VacA protein-protein interactions and the dominant-negative phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Escherichia coli DH5α was used for plasmid propagation and was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar at 37°C. For the expression of recombinant proteins, plasmids were transformed into E. coli strain ER2566 (New England Biolabs), which carries an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible copy of the RNA polymerase gene in bacteriophage T7. Transformants were grown in Terrific broth (TB; Invitrogen) supplemented with 25 μg/ml of kanamycin (TB-KAN). H. pylori wild-type strain 60190 (ATCC 49503), strain AV452 (expressing the Δ6-27p88 VacA protein) (43), and strain VT330 (expressing a c-Myc epitope-tagged wild-type VacA protein [p88c-Myc]) (25) were grown on Trypticase soy agar plates containing 5% sheep blood at 37°C in ambient air containing 5% CO2. H. pylori liquid cultures were grown in sulfite-free Brucella broth supplemented with 0.5% activated charcoal (20).

Purification of VacA from H. pylori.

Wild-type VacA, p88c-Myc, and Δ6-27p88 proteins were purified in an oligomeric form from culture supernatants of H. pylori strains 60190, VT330, and AV452, respectively, as described previously (6). In all experiments, purified VacA preparations were acid activated by the addition of 250 mM hydrochloric acid, thereby lowering the pH to 3, before VacA was added to cell culture wells (12, 28).

Construction of VacA expression plasmids.

Several VacA-expressing plasmids used in this study have been described previously (26, 41). The new VacA-expressing plasmids used in this study were constructed using the PCR primer pairs listed in Tables 1 and 2, with plasmids pMM592 and pMM601, which encode wild-type and Δ6-27-VacA proteins, respectively, as templates (26). The PCR products were digested with SpeI and SalI or with SpeI and PstI and ligated into XbaI/SalI- or XbaI/PstI-digested pET-41b (conferring kanamycin resistance; Novagen). For the introduction of the in-frame Δ334-360, Δ334-341, Δ342-350, and Δ351-360 deletions into the plasmid encoding the Δ6-27p48His protein, we performed inverse PCR with the primers shown in Table 1, using the pVT315 plasmid (a pET41b plasmid encoding the Δ6-27p48His protein) as template DNA and Pfu Turbo polymerase (Stratagene). The resulting amplicons were then ligated and transformed into E. coli. Similarly, we introduced in-frame Δ334-341, Δ342-350, and Δ351-360 deletions into a p55His-expressing plasmid (41) by using the primers listed in Table 1. All of the new plasmids used in this study are described in Table 2. The numbering of VacA amino acids throughout this study is based on the sequence of VacA produced by wild-type H. pylori 60190 (GenBank accession number AAA17657), and the first amino acid (alanine) of the mature secreted VacA toxin is designated amino acid 1.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer | Nucleotide sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| AND3817 | CCCACTAGTAAGAGGAGACGCCATGTTTTTTACAACC |

| AND6003 | CCCCTGCAGCTCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGAGCGT |

| AGCTAGCGAAACG | |

| OP9133 | CCCCGTCGACTTAATTCTCAGTAGGCGTAGAATT |

| OP9135 | CCCCGTCGACTTATTTACTGATGCCTATATTTTTCCA |

| BAR1559 | CCCCGTCGACTTAGATTTTCGCTTTCAATAAAACA |

| BAR1558 | CCCCGTCGACTTAGCCAGTTTCCAAACGCACG |

| AND6001 | CCCCTGCAGCTCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGCGTATC |

| AATACCTTTAAAATTAG | |

| OP6228 | CCCTGCAGCTAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGTTTAGCAC |

| CACTTTGAGAAGG | |

| OPE1144 | CGAATCAACACTAAAGCCGATG |

| OPE1145 | CGAAATTGGGTGGGTTAATGA |

| OPE1216 | ACTATTGGGTGGGTTAATGACC |

| OPE1217 | ACTCAAGTCATTGATGGGCCTT |

| OPE1218 | GGGTTGAACTTCTGTTTTTTGC |

| OPE1219 | GGGGGCAAAGACACGGTTG |

| OPE1220 | CGCAAAAGGCCCATCAATGAC |

| OPE1221 | CGCATCAACACTAAAGCCGAT |

TABLE 2.

VacA expression plasmids generated in this study

| Expression plasmida | Forward primerb | Reverse primerb | Restriction enzymesc | Encoded VacA proteind |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pMM652 | AND3817 | AND6003 | SpeI/PstI | Δ(6-27)1-821-His |

| pVT562 | AND3817 | OP9133 | SpeI/SalI | Δ(6-27)1-800 |

| pVT561 | AND3817 | OP9135 | SpeI/SalI | Δ(6-27)1-780 |

| pVT560 | AND3817 | BAR1559 | SpeI/SalI | Δ(6-27)1-700 |

| pVT559 | AND3817 | BAR1558 | SpeI/SalI | Δ(6-27)1-550 |

| pVT315 | AND3817 | AND6001 | SpeI/PstI | Δ6-27p48-His |

| pVT148 | AND3817 | OP6228 | SpeI/PstI | Δ6-27p33-His |

| pVT587 | OPE1144 | OPE1145 | NAe | Δ(6-27/334-360)p48-His |

| pVT604 | OPE1216 | OPE1217 | NAe | Δ(6-27/334-341)p48-His |

| pVT606 | OPE1218 | OPE1219 | NAe | Δ(6-27/342-350)p48-His |

| pVT608 | OPE1220 | OPE1221 | NAe | Δ(6-27/351-360)p48-His |

| pVT597 | OPE1216 | OPE1217 | NAe | Δ334-341p55-His |

| pVT598 | OPE1218 | OPE1219 | NAe | Δ342-350p55-His |

| pVT600 | OPE1220 | OPE1221 | NAe | Δ351-360p55-His |

Each of these plasmids was derived from pET41b.

Oligonucleotides used to PCR amplify the different vacA sequences. Oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Table 1.

Restriction sites used to clone the PCR products into pET41b.

The VacA amino acid numbering system used in this table is based on designating the first amino acid (alanine) of the mature secreted VacA toxin of strain 60190 as amino acid 1. “Δ” indicates amino acids that are deleted from the mutant VacA fragments. “His” indicates the presence of a six-His tag. All of these VacA proteins that contain a Δ6-27 deletion also contain an alanine-to-methionine substitution at amino acid 1 (A1M) (26).

NA, not applicable. These plasmids containing in-frame internal deletions were constructed by inverse PCR as described in Materials and Methods.

Expression of recombinant VacA proteins.

E. coli ER2566 strains containing the different VacA-expressing plasmids were inoculated into TB-KAN and grown at 37°C overnight with shaking. E. coli strains expressing p55 or Δ6-27p48 protein were diluted 1:100 in TB-KAN and incubated at 25°C until they reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3 (26, 41). Cultures were then induced with a final IPTG concentration of 0.3 mM and incubated at 25°C for 16 to 18 h. E. coli strains expressing p33 proteins were diluted 1:100 in TB-KAN and incubated at 37°C until they reached an OD600 of 0.3. Cultures were then induced with a final IPTG concentration of 0.3 mM and incubated at 37°C for 2 h as described previously (26, 41). Extracts containing soluble proteins were generated as described previously and stored at −20°C until use (26, 41). As a negative control, we used an E. coli strain carrying the pET vector. This strain was induced with IPTG, similar to the E. coli strains that expressed recombinant VacA fragments. Extracts from this negative control strain did not exhibit inhibitory activity, regardless of whether the strain was grown at 37°C or 25°C.

Immunoblot analysis.

E. coli extracts containing VacA proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted with a polyclonal antiserum reactive with the His6 epitope (His probe, hereafter termed anti-His; Santa Cruz), a polyclonal anti-VacA serum (958) (34), or a monoclonal anti-c-Myc antibody (9E10), followed by secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Bio-Rad). Signals were generated by the enhanced chemiluminescence reaction (Amersham) and detected using X-ray film. In experiments requiring the use of multiple recombinant VacA proteins, the relative concentrations of recombinant VacA in different E. coli extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-His antibody, and the extracts were then normalized such that the relative concentrations of VacA in different preparations were approximately equivalent.

Cell culture and vacuolating assay.

HeLa cells were grown in minimal essential medium (modified Eagle's medium containing Earle's salts) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. For vacuolating assays, cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells per well into 96-well plates 24 h prior to each experiment. To test for dominant-negative activity, E. coli extracts containing the different recombinant VacA proteins were mixed with 15 μg/ml of purified acid-activated wild-type VacA in a final volume of 100 μl, and this mixture was then added to HeLa cells for 1 h at 37°C in the presence of 10 mM ammonium chloride and 50 μg/ml of gentamicin. Gentamicin was added to prevent the growth of bacterial contaminants. After incubation, the tissue culture medium was replaced with fresh FBS-free tissue culture medium containing 10 mM ammonium chloride and 50 μg/ml of gentamicin, and cells were incubated for 3 to 4 h at 37°C. Cell vacuolation was examined by inverted light microscopy and quantified by a neutral red uptake assay as described previously (8). Neutral red uptake data are presented as OD540 values (means ± standard deviations). Statistical significance was analyzed by using Student's t test.

Immunoprecipitation of VacA complexes.

E. coli extracts containing recombinant VacA proteins were mixed with acid-activated c-Myc-VacA (p88c-Myc) purified from H. pylori strain VT330 (2 μg/ml) and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Protein complexes containing p88c-Myc were immunoprecipitated with an anti-c-Myc monoclonal antibody (2 μg/ml of antibody 9E10) and protein G-coated beads (Amersham) as described previously (25, 41). Alternatively, E. coli extracts containing recombinant VacA proteins were mixed with extracts containing p33Myc-His or p55c-Myc, and protein complexes were immunoprecipitated with an anti-c-Myc antibody (25, 41). Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting as described above.

Analysis of VacA interactions with mammalian cells.

HeLa cells were grown on cover glasses in 12-well plates. To assess the interaction of VacA with the surfaces of cells, acid-activated wild-type p88 VacA (final concentration, 15 μg/ml) purified from an H. pylori culture supernatant and the Δ6-27p48His recombinant VacA protein were added to cells, either individually or as a mixture, for 1 h at 37°C. VacA interactions with the surfaces of cells were then analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence as described previously (41). Briefly, cells were washed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde. Fixed cells were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with an anti-VacA polyclonal antiserum (958) that recognizes the C-terminal region of p88 VacA. Cells were then washed and incubated with a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500) for 1 h at room temperature. Cover glasses were washed with TBS, mounted on slides with Aqua-Polymount (Polysciences, Warrington, PA), and viewed with an LSM 510 confocal laser scanning inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss).

To analyze the internalization of VacA, cells were incubated with acid-activated wild-type VacA and the recombinant Δ6-27p48His VacA protein, either individually or as a mixture, for 1 h at 37°C. Afterward, the tissue culture medium containing unbound proteins was removed, and the cells were incubated in fresh tissue culture medium (without FBS and with or without ammonium chloride, as indicated) for 8 to 24 h at 37°C. The cells were then washed with TBS, fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min at 25°C, permeabilized with 100% methanol for 30 min at −20°C (41), and analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence as described above.

RESULTS

Inhibition of vacuolating cytotoxic activity by a mixture of Δ6-27p33 and p55 VacA proteins.

Previously, we showed that a VacA mutant protein (Δ6-27p88 VacA) exhibits a dominant-negative phenotype when mixed in an equimolar ratio with wild-type VacA (26, 43). As a first step in mapping the region of VacA required for the dominant-negative phenotype, we investigated whether either the recombinant wild-type p33 or wild-type p55 VacA protein could inhibit the vacuolating cytotoxic activity of wild-type p88 VacA (Fig. 1A). E. coli extracts containing the recombinant Δ6-27p88, p33, or p55 VacA protein were generated as described previously (26, 41). Expression of the VacA proteins was confirmed by immunoblotting as described in Materials and Methods (data not shown). As expected, the Δ6-27p88 recombinant protein potently blocked the vacuolating cytotoxic activity of wild-type VacA (Fig. 1B) (26). In contrast, neither the p33 nor the p55 protein exhibited inhibitory activity (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Dominant-negative properties of Δ6-27p88 VacA. (A) Diagram of full-length wild-type VacA, two putative VacA domains (p33 and p55), and a VacA mutant protein (Δ6-27p88) that exhibits a dominant-negative phenotype. The VacA amino acid numbers are indicated, and the numbering system is described in Materials and Methods. (B) E. coli extracts containing the indicated recombinant VacA proteins were generated as described in Materials and Methods. An E. coli extract without VacA (pET) was used as a negative control. These protein preparations were mixed with acid-activated wild-type VacA purified from an H. pylori culture supernatant (H.p. VacA) and then incubated with HeLa cells as described in Materials and Methods. Vacuolating activity was measured by a neutral red uptake assay. Results represent the means ± standard deviations from triplicate samples. *, P < 0.05 for comparison with cells treated with H. pylori VacA plus control extract (pET).

We next investigated whether a p33 protein containing the Δ6-27 mutation could inhibit the vacuolating cytotoxin activity of wild-type VacA. As shown in Fig. 2, the Δ6-27p33 protein did not exhibit any inhibitory activity. We have shown previously that the wild-type p33 and p55 VacA proteins each lack vacuolating cytotoxic activity when added alone to cells but that, when mixed together, they interact with each other and can reconstitute vacuolating cytotoxic activity (41). Therefore, we investigated whether a mixture of the wild-type p55 protein and the Δ6-27p33 protein could reconstitute the dominant-negative phenotype. As shown in Fig. 2, the Δ6-27p33-p55 mixture potently inhibited the vacuolating activity of wild-type VacA, similar to the inhibitory effect exhibited by Δ6-27p88. In contrast, a mixture of Δ6-27p33 and the pET control extract or of p55 and the pET control extract did not inhibit the vacuolating activity of wild-type VacA (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Reconstitution of dominant-negative phenotype by mixing Δ6-27p33 and p55 VacA proteins. (A) Diagram of two putative Δ6-27p88 VacA domains (Δ6-27p33 and p55) and the VacA Δ6-27 mutant protein (Δ6-27p88). The VacA amino acid numbers are indicated, and the numbering system is described in Materials and Methods. (B) E. coli extracts containing the indicated recombinant VacA proteins were mixed with acid-activated wild-type VacA purified from an H. pylori culture supernatant (H.p. VacA). Samples were then incubated with HeLa cells, and vacuolating activity was measured by a neutral red uptake assay. Results represent the means ± standard deviations from triplicate samples. *, P < 0.05 for comparison with cells treated with H. pylori VacA plus control extract (pET).

Interactions of Δ6-27p33 with wild-type VacA.

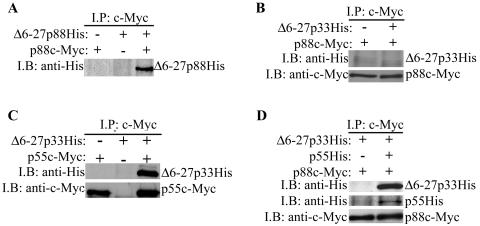

A current model presumes that the inhibitory activity of the Δ6-27p88 VacA protein is due to the formation of inactive mixed oligomeric complexes comprised of both wild-type and mutant VacA proteins (25, 43). In a previous study (41), we showed that p33 does not interact with p88 VacA in the absence of the p55 domain. We hypothesized that the Δ6-27p33 protein (in the absence of p55) lacked inhibitory activity due to an inability of Δ6-27p33 to form mixed oligomeric complexes with wild-type VacA. To test this hypothesis, we compared the abilities of Δ6-27p88 and Δ6-27p33 to physically interact with a c-Myc-tagged form of wild-type p88 VacA (p88c-Myc) (25). As expected, the recombinant Δ6-27p88 protein interacted with p88c-Myc VacA (Fig. 3A) (25). In contrast, we did not detect any interaction between Δ6-27p33 and p88c-Myc VacA (Fig. 3B). These data support the hypothesis that the formation of mixed oligomeric complexes is required for the dominant-negative phenotype.

FIG. 3.

Interactions of recombinant VacA proteins with c-Myc-tagged p88 VacA. E. coli extracts containing the indicated recombinant VacA proteins were mixed with purified acid-activated c-Myc-tagged p88 wild-type VacA (p88c-Myc) from an H. pylori culture supernatant, as indicated (A, B, and D). Alternatively, E. coli extracts containing Δ6-27p33His or p55c-Myc were mixed together as indicated (C). Protein complexes were immunoprecipitated (I.P.) with an anti-c-Myc antibody, electrophoresed in a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblotted (I.B.) with anti-His and anti-c-Myc antibodies, as indicated.

Since a mixture of p55 and Δ6-27p33 reconstituted the dominant-negative phenotype (Fig. 2), we investigated the ability of these proteins to form oligomeric complexes. We first demonstrated that the Δ6-27p33 and p55 proteins were able to physically interact with each other (Fig. 3C). We then investigated whether the mixture of Δ6-27p33 and p55 could interact with p88c-Myc VacA. Indeed, when the p88c-Myc protein was incubated with the Δ6-27p33-p55 mixture, the p88c-Myc protein interacted with both Δ6-27p33 and p55 (Fig. 3D). These data suggest that the failure of the isolated Δ6-27p33 protein to interact with wild-type p88 VacA and inhibit its activity was not due to misfolding of the Δ6-27p33 protein but, instead, was due to an absence of amino acid sequences found in the p55 domain.

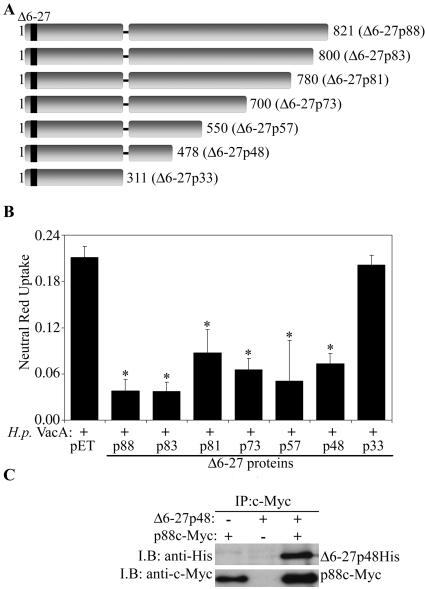

Mapping of a minimal region of Δ6-27p88 VacA that has inhibitory activity.

In an effort to map a minimal region of the Δ6-27p88 VacA protein capable of inhibiting the activity of wild-type VacA, we generated a series of Δ6-27p88 recombinant proteins truncated at the carboxyl terminus (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4B, most of the truncated Δ6-27p88 proteins were able to block the vacuolating activity of wild-type VacA. The smallest Δ6-27p88 fragment capable of inhibiting wild-type VacA activity corresponded to amino acids 1 to 478 (Δ6-27p48) (Fig. 4A). In contrast, a smaller Δ6-27p88 fragment, Δ6-27p33, did not exhibit detectable dominant-negative activity (Fig. 2B and 4B). The difference in the activities of Δ6-27p33 and Δ6-27p48 was not due to different concentrations of these proteins, because no inhibitory activity was detected even when we tested a substantially higher concentration of Δ6-27p33 (approximately 10-fold higher than the concentration of Δ6-27p48His, based on immunoblotting with an anti-His antibody) (data not shown). As expected, the wild-type VacA protein containing amino acids 1 to 478 (p48) did not exhibit a dominant-negative phenotype (data not shown). Based on the ability of the Δ6-27p48 protein to exhibit a dominant-negative phenotype, we hypothesized that it could physically interact with wild-type VacA to form mixed oligomeric complexes. As shown in Fig. 4C, we detected the formation of mixed oligomeric complexes comprised of Δ6-27p48 and p88c-Myc VacA.

FIG. 4.

Dominant-negative phenotype exhibited by truncated Δ6-27p88 VacA proteins. (A) Diagram of truncated Δ6-27 recombinant VacA proteins. The last amino acid of each truncated Δ6-27 recombinant VacA protein is indicated. (B) E. coli extracts containing different Δ6-27 recombinant VacA proteins were mixed with acid-activated wild-type VacA purified from an H. pylori culture supernatant (H.p. VacA) and incubated with HeLa cells. Vacuolating activity was measured by a neutral red uptake assay. Results represent the means ± standard deviations from triplicate samples. *, P < 0.05 for comparison with cells treated with H. pylori VacA plus control extract (pET). (C) E. coli extract containing the Δ6-27p48His VacA protein was mixed with purified acid-activated c-Myc-VacA (p88c-Myc) from an H. pylori culture supernatant, as indicated. Protein complexes were immunoprecipitated (I.P.) with an anti-c-Myc antibody, electrophoresed, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblotted (I.B.) with anti-His and anti-c-Myc antibodies, as indicated.

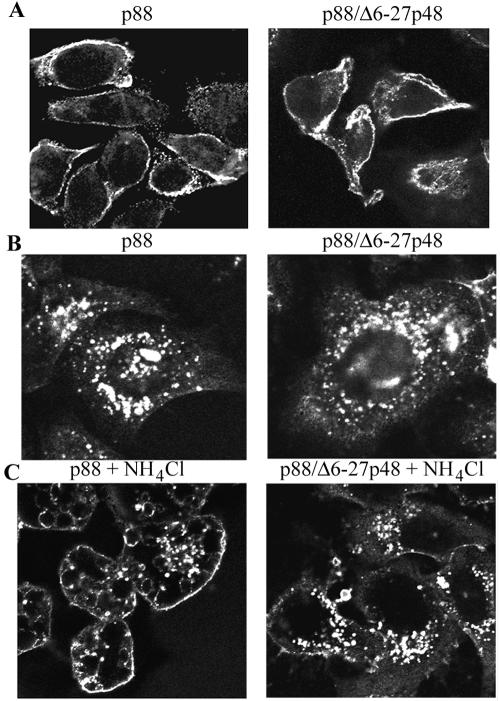

The Δ6-27p48 protein exhibits a dominant-negative phenotype without blocking binding or internalization of wild-type VacA.

Wild-type VacA causes cell vacuolation via a series of steps that include binding of VacA to the cell surface followed by internalization of the toxin (4, 17, 18, 22, 28). In the next series of experiments, we investigated whether the Δ6-27p48 protein blocked either binding of wild-type VacA to mammalian cells or entry of wild-type VacA into cells. The localization of wild-type p88 VacA was analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence methodology, as described in Materials and Methods (17, 41). As expected, when wild-type p88 VacA alone was added to HeLa cells, the p88 VacA protein bound to the cells and was internalized by cells (Fig. 5A and B, left panels) (17, 25, 41). No immunoreactive signal was detected following incubation of cells with the Δ6-27p48 protein or the negative control E. coli extract (data not shown). When a mixture of the Δ6-27p48 protein and wild-type p88 VacA was added to cells, wild-type VacA bound to the cell surface (Fig. 5A, right panel) and was internalized (Fig. 5B and C, right panels). Thus, the Δ6-27p48 protein inhibits the vacuolating cytotoxic activity of wild-type VacA but does not block binding or internalization of wild-type VacA.

FIG. 5.

Effects of Δ6-27p48 VacA dominant-negative protein on binding and internalization of wild-type VacA. (A) HeLa cells were intoxicated for 1 h at 37°C with wild-type acid-activated VacA (p88) purified from an H. pylori culture supernatant (left panel) or with a mixture of wild-type VacA (p88) and Δ6-27p48 (right panel). The capacity of the VacA proteins to interact with the cells was assessed by indirect immunofluorescence, using an anti-VacA polyclonal antiserum reactive with the C-terminal region of p88 VacA, as described in Materials and Methods. (B and C) Wild-type acid-activated VacA (p88) purified from an H. pylori culture supernatant (left panels) or a mixture of p88 and Δ6-27p48 (right panels) was added to HeLa cells in the absence (B) or presence (C) of 10 mM ammonium chloride, and cells were then incubated for 12 h at 37°C. The ability of wild-type VacA (p88) to enter cells was assessed by indirect immunofluorescence of permeabilized cells, using anti-VacA polyclonal antiserum.

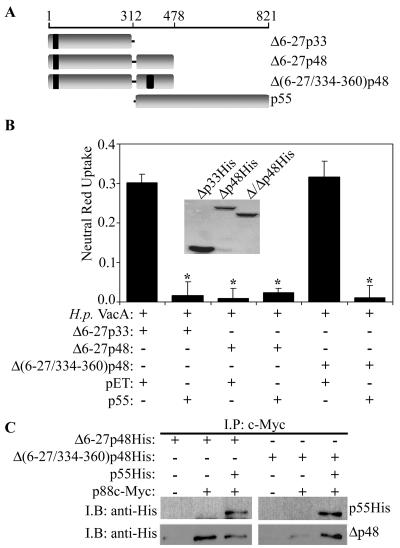

Amino acids 334 to 360 are required for the dominant-negative phenotype and the formation of mixed oligomeric complexes.

Based on the observed difference in the activities of Δ6-27p33 and Δ6-27p48, we hypothesized that amino acid sequences present exclusively in the larger protein (i.e., amino acids 313 to 478) are required for the dominant-negative phenotype and for the formation of mixed oligomeric complexes. Previously, it was shown that the deletion of amino acids 346 and 347 impairs VacA vacuolating cytotoxic activity (48). Therefore, we generated a Δ6-27p48 protein with an in-frame deletion in this region, designated Δ(6-27/334-360)p48 (Fig. 6A). In contrast to the Δ6-27p48 protein, the Δ(6-27/334-360)p48 protein lacked detectable inhibitory activity (Fig. 6B). Inhibitory activity was reconstituted by mixing the Δ(6-27/334-360)p48 protein and the wild-type p55 fragment (Fig. 6B). In comparison to Δ6-27p48, the Δ(6-27/334-360)p48 protein was defective in the ability to interact with p88c-Myc VacA (Fig. 6C). The formation of mixed oligomeric complexes containing p88c-Myc VacA and Δ(6-27/334-360)p48 was greatly enhanced when the p55 domain was added as a supplement (Fig. 6C). Together, these data indicate that amino acids 334 to 360 in VacA play an important role in the dominant-negative phenotype and the formation of mixed oligomeric complexes.

FIG. 6.

Role of VacA amino acids 334 to 360 in dominant-negative phenotype and the formation of mixed oligomeric complexes. (A) Diagram of three Δ6-27 VacA mutant proteins [Δ6-27p33, Δ6-27p48, and Δ(6-27/334-360)p48] and the p55 VacA domain. The VacA amino acid numbers are indicated, and the numbering system is described in Materials and Methods. (B) E. coli extracts containing the Δ6-27p33, Δ6-27p48, or Δ(6-27/334-360)p48 recombinant VacA protein were mixed with either an extract containing the p55 VacA protein or the negative control extract (pET) and tested for the ability to inhibit the vacuolating activity of acid-activated wild-type VacA purified from an H. pylori culture supernatant (H.p. VacA). Samples were incubated with HeLa cells, and vacuolating activity was measured by a neutral red uptake assay. Results represent the means ± standard deviations from triplicate samples. *, P < 0.05 for comparison with the control. The inset shows immunoblotting of the indicated proteins with an anti-His antibody. (C) E. coli extracts containing the Δ6-27p48His or Δ(6-27/334-360)p48His VacA protein individually or the Δ6-27p48His-p55His or Δ(6-27/334-360)p48His-p55His mixture were combined with purified acid-activated c-Myc-VacA (p88c-Myc) from an H. pylori culture supernatant, as indicated. Protein complexes were immunoprecipitated (I.P.) with an anti-c-Myc antibody, electrophoresed, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblotted (I.B.) with the indicated antibodies.

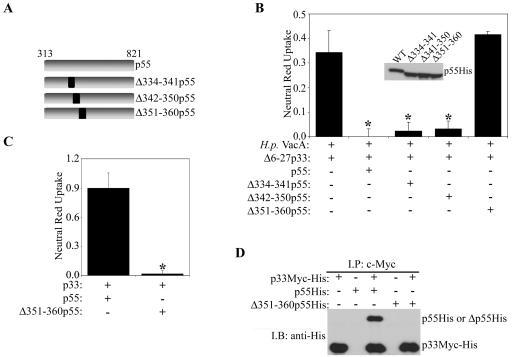

Amino acids 351 to 360 are required for the dominant-negative phenotype and the formation of mixed oligomeric complexes.

To further map the region of VacA that is required for the dominant-negative phenotype and the formation of mixed oligomeric complexes, we introduced three small in-frame deletions into Δ6-27p48 [Δ(6-27/334-341)p48, Δ(6-27/342-350)p48, and Δ(6-27/351-360)p48] (Fig. 7A). Both the Δ(6-27/334-341)p48 and Δ(6-27/342-350)p48 proteins exhibited potent inhibitory activities similar to that exhibited by the Δ6-27p48 protein (Fig. 7B). In contrast, the Δ(6-27/351-360)p48 protein did not exhibit detectable inhibitory activity (Fig. 7B). Inhibitory activity was reconstituted by mixing Δ(6-27/351-360)p48 with the wild-type p55 protein (Fig. 7B). As expected, the Δ(6-27/351-360)p48 protein was defective in the ability to interact with p88c-Myc VacA (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Role of VacA amino acids 351 to 360 in dominant-negative phenotype. (A) Diagram of recombinant Δ6-27p48 VacA proteins. “Δ” indicates amino acids deleted in the mutant p48 VacA proteins. (B) E. coli extracts containing the indicated Δ6-27p48 recombinant VacA proteins were mixed with either a negative control extract (pET) or an extract containing the p55 VacA protein and then tested for the ability to inhibit the activity of acid-activated wild-type VacA purified from an H. pylori culture supernatant (H.p. VacA). Samples were incubated with HeLa cells, and vacuolating activity was measured by a neutral red uptake assay. Results represent the means ± standard deviations from triplicate samples. *, P < 0.05 for comparison with cells treated with H. pylori VacA plus control extract (pET).

We also investigated whether the deletion of amino acids 334 to 341, 342 to 350, or 351 to 360 (Fig. 8A) would affect the ability of the p55 domain to reconstitute the dominant-negative phenotype when mixed with Δ6-27p33 (Fig. 2). A mixture of the Δ6-27p33 protein and wild-type p55, Δ334-341p55, or Δ342-350p55 exhibited a strong inhibitory activity (Fig. 8B). In contrast, a mixture of Δ6-27p33 and Δ351-360p55 did not exhibit detectable inhibitory activity. These data indicate that VacA amino acids 351 to 360 (GGKDTVVNID) are required for the dominant-negative phenotype.

FIG. 8.

Role of amino acids 351 to 360 in VacA-induced cell vacuolation and formation of p33/p55 oligomeric complexes. (A) Diagram of recombinant p55 VacA proteins. (B) E. coli extracts containing the Δ6-27p33 VacA protein were mixed with extracts containing wild-type p55 or p55 proteins containing the indicated in-frame deletions. Mixtures were then tested for the ability to inhibit the activity of acid-activated wild-type VacA purified from an H. pylori culture supernatant (H.p. VacA). Samples were incubated with HeLa cells, and vacuolating activity was measured by a neutral red uptake assay. Results represent the means ± standard deviations from triplicate samples. *, P < 0.05 for comparison with the control. The inset shows immunoblotting of the indicated p55 VacA proteins with an anti-His antibody. (C) E. coli extracts containing wild-type p33Myc-His and p55His or wild-type p33Myc-His and Δ351-360p55His were mixed and added to HeLa cells. Vacuolating cytotoxic activity was measured by a neutral red uptake assay. Results represent the means ± standard deviations from triplicate samples. *, P < 0.05. (D) E. coli extracts were mixed as indicated. Protein complexes were immunoprecipitated (I.P.) with an anti-c-Myc antibody, electrophoresed, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblotted (I.B.) with an anti-His antibody.

Amino acids 351 to 360 are required for vacuolating cytotoxic activity.

Finally, we investigated whether amino acids 351 to 360 are required for the vacuolating cytotoxic activity of wild-type VacA. As shown previously (41), a mixture of wild-type p33 and wild-type p55 proteins exhibited extensive vacuolating cytotoxic activity (Fig. 8C). In contrast, a mixture of p33 and Δ351-360p55 did not exhibit detectable vacuolating cytotoxic activity (Fig. 8C). As expected, we did not detect an interaction of the Δ351-360p55 protein with p33c-Myc-His (Fig. 8D). These data provide further evidence for an important role of amino acids 351 to 360 and indicate that these amino acids are required for interactions between the p33 and p55 domains.

DISCUSSION

In previous studies, we showed that a VacA mutant protein, Δ6-27p88, is able to inhibit the activity of wild-type VacA in a dominant-negative manner (7, 25, 26, 38, 43, 45, 46). In the current study, we provide an analysis of the structural features of Δ6-27p88 VacA that are required in order for this protein to exhibit a dominant-negative phenotype. We show that a Δ6-27 VacA protein containing the first 478 amino acids of VacA (Δ6-27p48) exhibits a dominant-negative phenotype similar to that of the full-length Δ6-27p88 VacA protein (Fig. 4). It is notable that a wild-type VacA fragment containing amino acids 1 to 478 exhibits vacuolating activity when expressed within HeLa cells (50). Thus, wild-type VacA amino acids 1 to 478 are sufficient for intracellular vacuolating activity, and this same region is sufficient for the dominant-negative phenotype when a Δ6-27 mutation is present.

We have shown previously that the Δ6-27p88 protein produced by H. pylori is able to form mixed oligomeric complexes with wild-type VacA (25). Furthermore, when cells are transiently cotransfected with plasmids expressing wild-type and Δ6-26 VacA proteins, the Δ6-26 VacA protein is able to interact with wild-type VacA (47). Therefore, the formation of functionally inactive mixed oligomeric complexes provides a possible mechanistic basis for the dominant-negative phenotype. In the current study, we provide several lines of experimental evidence in support of this model. Specifically, we demonstrate that the Δ6-27p48 VacA protein, which has dominant-negative activity, is able to form mixed oligomeric complexes comprising Δ6-27p48 and wild-type p88 VacA (Fig. 4). In contrast, the Δ6-27p33 VacA protein, which lacks dominant-negative activity, is not able to interact with wild-type p88 VacA (Fig. 3B). We show that the introduction of a Δ334-360 mutation into Δ6-27p48 diminishes its capacity to form mixed oligomeric complexes and results in a loss of the dominant-negative phenotype (Fig. 6). We also show that the dominant-negative phenotype and the ability to form mixed oligomeric complexes are reconstituted when either Δ6-27p33 or Δ(6-27/334-360)p48 is mixed in trans with the p55 domain.

As described in this study, two important structural features of Δ6-27p88 are required for the dominant-negative phenotype, i.e., the presence of the Δ6-27 deletion within the p33 domain and the presence of amino acid sequences derived from the p55 domain. VacA amino acids 6 to 27 are predicted to comprise a hydrophobic region (43). GXXXG motifs found within this region are required for transmembrane oligomerization and membrane channel formation (24, 27). These data suggest that amino acids 6 to 27 comprise a membrane-spanning domain. The experimental data presented here indicate that amino acid sequences in the region between amino acids 312 and 478 have a role in the formation of mixed oligomeric complexes. In a previous study, we showed that this region of VacA (amino acids 312 to 478) can interact with the p33 VacA domain in a yeast two-hybrid system (42), and this interaction is probably relevant in the formation of mixed oligomeric complexes. In addition, cotransfection of HeLa cells with a plasmid encoding the wild-type p33 VacA domain and a plasmid encoding VacA amino acids 312 to 478 can reconstitute vacuolating cytotoxic activity (50). Together, these observations suggest that amino acids 312 to 478 comprise a domain that has important functional properties. The mutational experiments described here indicate that within this domain, amino acids 351 to 360 have an important role in the formation of VacA oligomeric complexes, are essential for the dominant-negative phenotype, and are essential for the vacuolating activity of wild-type VacA. A comparison of VacA proteins produced by unrelated H. pylori strains reveals that this region (i.e., amino acids 351 to 360) is conserved, which is consistent with the hypothesis that it plays an essential function, most likely related to VacA oligomerization.

Previously, we have shown that the Δ6-27p88 VacA protein can inhibit the capacity of wild-type VacA to form channels in planar lipid bilayers (43). Potentially mixed oligomeric complexes comprising wild-type VacA and Δ6-27p88 fail to insert into host cell membranes, and this might explain how the activity of wild-type VacA is blocked. In the current study, we demonstrate that the Δ6-27p48 VacA protein does not cause detectable alterations in the binding or internalization of wild-type VacA (Fig. 5). However, it remains possible that dominant-negative VacA proteins might cause subtle alterations in the intracellular trafficking or intracellular localization of wild-type VacA that are not detectable with current methods.

Protein toxins produced by many different organisms act by forming pores in cell membranes. The ability of dominant-negative mutant proteins to block the actions of pore-forming toxins is of considerable interest, since such dominant-negative proteins could potentially be useful as potent and specific therapeutic agents. Dominant-negative forms of bacterial pore-forming toxins have been described previously for H. pylori VacA (25, 43), the protective antigen component of anthrax toxin (30, 35, 36), and cytolysin A (ClyA) of E. coli (44). It is thought that these dominant-negative toxins must be able to form mixed oligomeric complexes with wild-type toxins in order to exhibit inhibitory activity. The potential therapeutic usefulness of dominant-negative inhibitors is highlighted by the development of dominant-negative forms of protective antigen, which can protect mice from challenges with lethal doses of wild-type anthrax toxin (35, 36). In the future, it will be important to assess whether dominant-negative mutants can be generated for other pore-forming toxins and whether such dominant-negative inhibitors could potentially represent useful new therapeutic agents.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants RO1-AI39657 and -DK53623 and by a medical research grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs (T.L.C.). V. J. Torres was supported in part by an NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein predoctoral fellowship (GM070061-02). M. S. McClain was supported in part by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Intramural Discovery Grant Program. The Vanderbilt University DNA Sequencing Laboratory and Cell Imaging Core Laboratory are supported by the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center.

We thank Beverly Hosse, Jeremy Ramsey, Valerie Acoff, Keith Hsu, and Yi Li for assistance with experiments and Carmen Ana Perez for helpful discussions.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Adrian, M., T. L. Cover, J. Dubochet, and J. E. Heuser. 2002. Multiple oligomeric states of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin demonstrated by cryo-electron microscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 318:121-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atherton, J. C., P. Cao, R. M. Peek, Jr., M. K. Tummuru, M. J. Blaser, and T. L. Cover. 1995. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. Association of specific vacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J. Biol. Chem. 270:17771-17777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boncristiano, M., S. R. Paccani, S. Barone, C. Ulivieri, L. Patrussi, D. Ilver, A. Amedei, M. M. D'Elios, J. L. Telford, and C. T. Baldari. 2003. The Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin inhibits T cell activation by two independent mechanisms. J. Exp. Med. 198:1887-1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cover, T. L., and S. R. Blanke. 2005. Helicobacter pylori VacA, a paradigm for toxin multifunctionality. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:320-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cover, T. L., and M. J. Blaser. 1992. Purification and characterization of the vacuolating toxin from Helicobacter pylori. J. Biol. Chem. 267:10570-10575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cover, T. L., P. I. Hanson, and J. E. Heuser. 1997. Acid-induced dissociation of VacA, the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin, reveals its pattern of assembly. J. Cell Biol. 138:759-769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cover, T. L., U. S. Krishna, D. A. Israel, and R. M. Peek, Jr. 2003. Induction of gastric epithelial cell apoptosis by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. Cancer Res. 63:951-957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cover, T. L., W. Puryear, G. I. Pérez-Pérez, and M. J. Blaser. 1991. Effect of urease on HeLa cell vacuolation induced by Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin. Infect. Immun. 59:1264-1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cover, T. L., M. K. R. Tummuru, P. Cao, S. A. Thompson, and M. J. Blaser. 1994. Divergence of genetic sequences for the vacuolating cytotoxin among Helicobacter pylori strains. J. Biol. Chem. 269:10566-10573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Czajkowsky, D. M., H. Iwamoto, T. L. Cover, and Z. Shao. 1999. The vacuolating toxin from Helicobacter pylori forms hexameric pores in lipid bilayers at low pH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2001-2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Czajkowsky, D. M., H. Iwamoto, G. Szabo, T. L. Cover, and Z. Shao. 2005. Mimicry of a host anion channel by a Helicobacter pylori pore-forming toxin. Biophys. J. 89:3093-3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Bernard, M., E. Papini, V. de Filippis, E. Gottardi, J. Telford, R. Manetti, A. Fontana, R. Rappuoli, and C. Montecucco. 1995. Low pH activates the vacuolating toxin of Helicobacter pylori, which becomes acid and pepsin resistant. J. Biol. Chem. 270:23937-23940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn, B. E., H. Cohen, and M. J. Blaser. 1997. Helicobacter pylori. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:720-741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Bez, C., M. Adrian, J. Dubochet, and T. L. Cover. 2005. High resolution structural analysis of Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin oligomers by cryo-negative staining electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 151:215-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figueiredo, C., J. C. Machado, P. Pharoah, R. Seruca, S. Sousa, R. Carvalho, A. F. Capelinha, W. Quint, C. Caldas, L. J. van Doorn, F. Carneiro, and M. Sobrinho-Simoes. 2002. Helicobacter pylori and interleukin 1 genotyping: an opportunity to identify high-risk individuals for gastric carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 94:1680-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujikawa, A., D. Shirasaka, S. Yamamoto, H. Ota, K. Yahiro, M. Fukada, T. Shintani, A. Wada, N. Aoyama, T. Hirayama, H. Fukamachi, and M. Noda. 2003. Mice deficient in protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type Z are resistant to gastric ulcer induction by VacA of Helicobacter pylori. Nat. Genet. 33:375-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garner, J. A., and T. L. Cover. 1996. Binding and internalization of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin by epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 64:4197-4203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gauthier, N. C., P. Monzo, V. Kaddai, A. Doye, V. Ricci, and P. Boquet. 2005. Helicobacter pylori VacA cytotoxin: a probe for a clathrin-independent and Cdc42-dependent pinocytic pathway routed to late endosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:4852-4866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gebert, B., W. Fischer, E. Weiss, R. Hoffmann, and R. Haas. 2003. Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin inhibits T lymphocyte activation. Science 301:1099-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawrylik, S. J., D. J. Wasilko, S. L. Haskell, T. D. Gootz, and S. E. Lee. 1994. Bisulfite or sulfite inhibits growth of Helicobacter pylori. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:790-792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leunk, R. D., P. T. Johnson, B. C. David, W. G. Kraft, and D. R. Morgan. 1988. Cytotoxic activity in broth-culture filtrates of Campylobacter pylori. J. Med. Microbiol. 26:93-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, Y., A. Wandinger-Ness, J. R. Goldenring, and T. L. Cover. 2004. Clustering and redistribution of late endocytic compartments in response to Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:1946-1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lupetti, P., J. E. Heuser, R. Manetti, P. Massari, S. Lanzavecchia, P. L. Bellon, R. Dallai, R. Rappuoli, and J. L. Telford. 1996. Oligomeric and subunit structure of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. J. Cell Biol. 133:801-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClain, M. S., P. Cao, and T. L. Cover. 2001. Amino-terminal hydrophobic region of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA) mediates transmembrane protein dimerization. Infect. Immun. 69:1181-1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McClain, M. S., P. Cao, H. Iwamoto, A. D. Vinion-Dubiel, G. Szabo, Z. Shao, and T. L. Cover. 2001. A 12-amino-acid segment, present in type s2 but not type s1 Helicobacter pylori VacA proteins, abolishes cytotoxin activity and alters membrane channel formation. J. Bacteriol. 183:6499-6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McClain, M. S., and T. L. Cover. 2003. Expression of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin in Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 71:2266-2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McClain, M. S., H. Iwamoto, P. Cao, A. D. Vinion-Dubiel, Y. Li, G. Szabo, Z. Shao, and T. L. Cover. 2003. Essential role of a GXXXG motif for membrane channel formation by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 278:12101-12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McClain, M. S., W. Schraw, V. Ricci, P. Boquet, and T. L. Cover. 2000. Acid-activation of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA) results in toxin internalization by eukaryotic cells. Mol. Microbiol. 37:433-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molinari, M., M. Salio, C. Galli, N. Norais, R. Rappuoli, A. Lanzavecchia, and C. Montecucco. 1998. Selective inhibition of Ii-dependent antigen presentation by Helicobacter pylori toxin VacA. J. Exp. Med. 187:135-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mourez, M., M. Yan, D. B. Lacy, L. Dillon, L. Bentsen, A. Marpoe, C. Maurin, E. Hotze, D. Wigelsworth, R. A. Pimental, J. D. Ballard, R. J. Collier, and R. K. Tweten. 2003. Mapping dominant-negative mutations of anthrax protective antigen by scanning mutagenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:13803-13808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakayama, M., M. Kimura, A. Wada, K. Yahiro, K. Ogushi, T. Niidome, A. Fujikawa, D. Shirasaka, N. Aoyama, H. Kurazono, M. Noda, J. Moss, and T. Hirayama. 2004. Helicobacter pylori VacA activates the p38/activating transcription factor 2-mediated signal pathway in AZ-521 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279:7024-7028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen, V. Q., R. M. Caprioli, and T. L. Cover. 2001. Carboxy-terminal proteolytic processing of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin. Infect. Immun. 69:543-546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmitt, W., and R. Haas. 1994. Genetic analysis of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin: structural similarities with the IgA protease type of exported protein. Mol. Microbiol. 12:307-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schraw, W., Y. Li, M. S. McClain, F. G. van der Goot, and T. L. Cover. 2002. Association of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin (VacA) with lipid rafts. J. Biol. Chem. 277:34642-34650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sellman, B. R., M. Mourez, and R. J. Collier. 2001. Dominant-negative mutants of a toxin subunit: an approach to therapy of anthrax. Science 292:695-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh, Y., H. Khanna, A. P. Chopra, and V. Mehra. 2001. A dominant negative mutant of Bacillus anthracis protective antigen inhibits anthrax toxin action in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 276:22090-22094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suerbaum, S., and P. Michetti. 2002. Helicobacter pylori infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:1175-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sundrud, M. S., V. J. Torres, D. Unutmaz, and T. L. Cover. 2004. Inhibition of primary human T cell proliferation by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin (VacA) is independent of VacA effects on IL-2 secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:7727-7732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szabo, I., S. Brutsche, F. Tombola, M. Moschioni, B. Satin, J. L. Telford, R. Rappuoli, C. Montecucco, E. Papini, and M. Zoratti. 1999. Formation of anion-selective channels in the cell plasma membrane by the toxin VacA of Helicobacter pylori is required for its biological activity. EMBO J. 18:5517-5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Telford, J. L., P. Ghiara, M. Dell'Orco, M. Comanducci, D. Burroni, M. Bugnoli, M. F. Tecce, S. Censini, A. Covacci, Z. Xiang, E. Papini, C. Montecucco, L. Parente, and R. Rappuoli. 1994. Gene structure of the Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin and evidence of its key role in gastric disease. J. Exp. Med. 179:1653-1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torres, V. J., S. E. Ivie, M. S. McClain, and T. L. Cover. 2005. Functional properties of the p33 and p55 domains of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 280:21107-21114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torres, V. J., M. S. McClain, and T. L. Cover. 2004. Interactions between p-33 and p-55 domains of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA). J. Biol. Chem. 279:2324-2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vinion-Dubiel, A. D., M. S. McClain, D. M. Czajkowsky, H. Iwamoto, D. Ye, P. Cao, W. Schraw, G. Szabo, S. R. Blanke, Z. Shao, and T. L. Cover. 1999. A dominant negative mutant of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin (VacA) inhibits VacA-induced cell vacuolation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:37736-37742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wai, S. N., M. Westermark, J. Oscarsson, J. Jass, E. Maier, R. Benz, and B. E. Uhlin. 2003. Characterization of dominantly negative mutant ClyA cytotoxin proteins in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:5491-5499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Willhite, D. C., and S. R. Blanke. 2004. Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin enters cells, localizes to the mitochondria, and induces mitochondrial membrane permeability changes correlated to toxin channel activity. Cell Microbiol. 6:143-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willhite, D. C., T. L. Cover, and S. R. Blanke. 2003. Cellular vacuolation and mitochondrial cytochrome c release are independent outcomes of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin activity that are each dependent on membrane channel formation. J. Biol. Chem. 278:48204-48209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willhite, D. C., D. Ye, and S. R. Blanke. 2002. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin within mammalian cells. Infect. Immun. 70:3824-3832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye, D., and S. R. Blanke. 2002. Functional complementation reveals the importance of intermolecular monomer interactions for Helicobacter pylori VacA vacuolating activity. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1243-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ye, D., and S. R. Blanke. 2000. Mutational analysis of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin amino terminus: identification of amino acids essential for cellular vacuolation. Infect. Immun. 68:4354-4357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ye, D., D. C. Willhite, and S. R. Blanke. 1999. Identification of the minimal intracellular vacuolating domain of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 274:9277-9282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]