Abstract

Background

The Term Breech Trial compared the safety of planned cesarean and planned vaginal birth for breech presentations at term. The combined outcome of perinatal or neonatal death and serious neonatal morbidity was found to be significantly lower among babies delivered by planned cesarean section. In this study we conducted a cost analysis of the 2 approaches to breech presentations at delivery.

Methods

We used a third-party–payer (i.e., Ministry of Health) perspective. We included all costs for physician services and all hospital-related costs incurred by both the mother and the infant. We collected health care utilization and outcomes for all study participants during the trial. We used only the utilization data from countries with low national rates of perinatal death (≤ 20/1000). Seven hospitals across Canada (4 teaching and 3 community centres) were selected for unit cost calculations.

Results

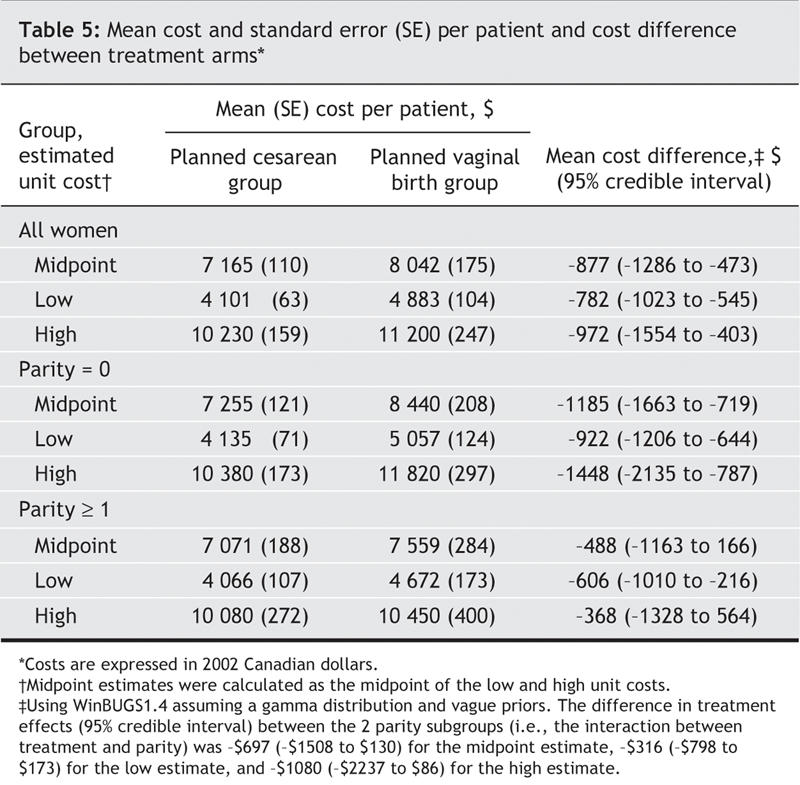

The estimated mean cost of a planned cesarean was significantly lower than that of a planned vaginal birth ($7165 v. $8042 per mother and infant; mean difference –$877, 95% credible interval –$1286 to –$473). The estimated mean cost of a planned cesarean was lower than that of a planned vaginal birth for both women having a first birth ($7255 v. $8440) and women having had at least one prior birth ($7071 v. $7559). Although the treatment effect was largest in the subgroup of women having their first child, there was no statistically significant interaction between treatment and parity since the 95% credible intervals for difference in treatment effects between parity equalling zero and parity of one or greater all include zero.

Interpretation

Planned cesarean section was found to be less costly than planned vaginal birth for the singleton fetus in a breech presentation at term in the Term Breech Trial.

The Term Breech Trial was a large multicentre, international randomized controlled trial that was conducted to determine whether planned cesarean was safer than planned vaginal birth for the delivery of the singleton fetus in frank or complete breech presentation at term. The study involved 2088 women from 121 centres in 26 countries. Participants were randomly assigned to either planned cesarean or planned vaginal birth. Data were received for 2083 women. Of the 1041 women assigned to the planned cesarean group, 941 (90.4%) actually delivered by cesarean; of the 1042 women assigned to the planned vaginal birth group, 591 (56.7%) delivered vaginally. The study's main findings were that the combined outcome of perinatal or neonatal death and serious neonatal morbidity, excluding lethal congenital anomalies, was significantly lower in the planned cesarean group than in the planned vaginal birth group (17/1039 [1.6%] v. 52/1039 [5.0%], relative risk [RR] 0.33, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.19–0.56), and that there were no statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of maternal rates of death or serious maternal morbidity (41/1041 [3.9%] v. 33/1042 [3.2%], RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.79–1.95).1

In this study we sought to determine whether a policy of planned cesarean section in the event of breech presentation is more or less expensive than a policy of planned vaginal birth. We report the estimated cost of each management strategy and discuss the economic and policy implications of our findings.

Methods

A detailed description of the Term Breech Trial and its findings can be found elsewhere.1,2 In brief, the study involved women with a singleton live fetus in a frank or complete breech presentation at term. Women were excluded if there was evidence of fetopelvic disproportion, if the fetus was judged to be clinically large or to have an estimated fetal weight of 4000 g or more, if there was hyperextension of the fetal head, if the clinician judged there to be a fetal anomaly or condition that might cause a mechanical problem at delivery (such as hydrocephalus), or if there was a contraindication to either labour or vaginal delivery (such as placenta previa). Women were also excluded if there was a known lethal fetal congenital anomaly.

The study (including the economic component) was approved by the research ethics committees of all participating centres, and the women who participated gave informed consent before enrolling in the trial. For women assigned to the planned cesarean group, a cesarean section was scheduled for 38 weeks' gestation or later. If the woman was in labour at the time of randomization, the cesarean was undertaken as soon as possible. If the patient was assigned to the planned vaginal birth group, management was expectant until spontaneous labour began, unless an indication to induce labour or to undertake a cesarean developed. If fetal heart-rate abnormalities or lack of progress in labour occurred, a cesarean was undertaken; otherwise labour was allowed to progress and the baby was delivered vaginally. Vaginal breech deliveries were undertaken by experienced clinicians, who were identified a priori and who were defined as those who considered themselves to be skilled and experienced at vaginal breech delivery, as confirmed by their respective heads of departments.

The cost analysis was undertaken from the perspective of a third-party payer (e.g., Ministry of Health). Costing hospital services involved determining health care resource use and associated unit costs. Health care resource use was collected for all women and infants who participated in the trial, but for this analysis we used only the resources used by women and infants recruited from countries with low (≤ 20/1000) national rates of perinatal death, as reported in 1996 by the World Health Organization.3 This was done to increase the likelihood that the results would be applicable to the Canadian system. These countries are Australia, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Israel, Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Switzerland, the UK, the United States and Yugoslavia.3

When planning the trial, it was anticipated that costs incurred during hospital stays would depend on 2 principal factors: lengths of stay of mothers and infants in the different locations within the hospital (i.e., representing different levels of intensity of care) and visits and procedures provided by physicians. Information on health care utilization up to 6 weeks postpartum was collected from the case report forms for all mothers and infants. The information included dates and times of admission to hospital, admission to the labour and delivery ward, admission to the operating room and discharge from the operating room as well as the date and time of birth. The date and time of discharge from hospital was also collected for mothers and infants, along with the time that the infant spent in a neonatal intermediate care unit or neonatal intensive care unit.

The length of stay in the antenatal ward was defined as the number of hours from admission to hospital or randomization — whichever was later — to admission to the labour and delivery ward or operating room — whichever was sooner. The length of stay in the labour and delivery ward for women having a vaginal birth was defined as the time from admission to the labour and delivery ward or randomization — whichever was later — to the time of delivery, plus one extra hour to account for the time for initial post-delivery recovery. For women having a cesarean section, the length of stay in the labour and delivery ward was defined as the time from admission to the labour and delivery ward or randomization — whichever was later — to the time of admission to the operating room, plus one extra hour to account for the time for initial post-cesarean recovery. The length of stay in the operating room was defined as the time from admission to the operating room or randomization — whichever was later — to the time of discharge from the operating room. The length of time in the postpartum ward was defined as starting at delivery for women having a vaginal birth, or at discharge from the operating room for women having a cesarean section, to the time of discharge from the hospital, minus one hour that was attributed to initial post-delivery recovery time spent in the labour and delivery ward.

Procedures and visits provided by physicians included weekly antenatal visits; induction or augmentation of labour or both with oxytocin or prostaglandins or both; analgesia or anesthesia or both; attendance at vaginal delivery or at cesarean section; and the provision of care for neonates in a normal nursery, neonatal intermediate care unit or neonatal intensive care unit. We classified the deliveries as vaginal breech, vaginal cephalic, prelabour cesarean or cesarean in labour, and because of the fee structure they were also categorized according to the time and day that they took place as follows: deliveries during the day (i.e., Monday to Friday from 0700 until 1700), deliveries during the evening or weekend (i.e., Saturday or Sunday from 0700 until 2400 or Monday to Friday from 1700 until 2400) and deliveries during the night (i.e., any day of the week between 0000 and 0700).

The provision of analgesia and anesthesia was categorized according to the time and day when it was started and its duration. The duration of anesthetic care for women having epidural anesthesia was calculated from the time when it was started until the time of delivery if the delivery was vaginal, or until 30 minutes after discharge from the operating room for cesarean sections. The duration of anesthetic care for women having a spinal or a general anesthetic was calculated either from the time when it was started (if recorded) or 15 minutes after admission into the operating room (if not recorded) until 30 minutes after discharge from the operating room. We also assumed that when more than one anesthetic was provided they were given one at a time. However, for the few cases when both epidural and spinal anesthesia were given to a woman having a vaginal delivery, it was assumed that this was combined spinal–epidural anesthesia and was treated as epidural anesthesia.

Although the use of health care resources was recorded in the trial, the associated unit costs were collected after the trial for the fiscal year 2002–2003. Reliable unit costs for health care services were not readily available and had to be calculated using financial and statistical reports provided by each hospital. We obtained reports from 4 teaching hospitals and 3 community hospitals in 3 provinces (British Columbia, Alberta and Ontario). The hospitals were chosen because of their accessibility and quality of financial information.4 Physician fees for the services were obtained from the respective provincial fee schedules.5–7 We contacted health care experts and clinicians from each province to assist us with the identification and interpretation of the most appropriate fees. For each service provided by a physician we took into consideration the time of day when these services were provided.

To determine unit costs for services provided in the hospital, a cost model of each participating hospital was developed. First, we identified in each hospital a group of women and infants who presented with similar characteristics to those who participated in the Term Breech Trial. To do so, we used the International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (ICD-10)8 codes Z37.0 (single live birth) and O32.10 (maternal care for breech presentation) or O64.10 (obstructed labour due to breech presentation), classified according to Case Mix Groups (CMGs)9 601–4 (cesareans and repeat cesareans with or without a complicating diagnosis), 607–11 (vaginal births before or after cesarean with or without minor procedures or a complicating diagnosis or both), 627–28 (neonates 1000–1499 g in weight with or without a catastrophic diagnosis), 630–32 (neonates 1500–1999 g in weight with or without problems or a catastrophic diagnosis or both), 637–40 (neonates 2000–2499 g in weight with or without problems or a catastrophic diagnosis), 643–45 (neonates > 2500 g in weight with a catastrophic diagnosis or major or moderate problems), 646 (neonates > 2500 g in weight born by cesarean) and 647–48 (neonates > 2500 g in weight with or without minor problems). Hospitals provided all direct and indirect (i.e., overhead) costs for these mothers and infants related to their length of stay at the hospital. We assumed that postpartum ward costs would be used as a proxy for antenatal ward costs because the nurse-to-patient ratio and intensity of care were similar in both locations.

Second, because we had very few vaginal breech cases and very few admissions to the neonatal intensive care unit, we added a data set of cephalic vaginal deliveries in 6 of the 7 hospitals. These we identified by ICD-10 code Z37.0 without O32.10 or O64.10, classified according to CMGs 607–11, 627–28, 630–32, 637–40, 643–45 and 647–48.

Third, each hospital provided us with the duration of stay of the women and infants in the different wards or rooms of the hospital, and we allocated the costs of different services to these wards or rooms. The cost of each service that was allocated to each ward or room of the hospital was then divided by the total length of stay in that ward or room to obtain the per-hour cost of each service. To find the total per-hour unit cost for each ward or room, we added the per-hour costs of all of the services that occurred in that ward or room.

Fourth, because unit cost estimates varied across the 7 hospitals and physician fees varied between the different provinces, we used the unit cost at the midpoint between the high and low unit cost estimates for the analysis.

All of the results were analyzed according to the intention to treat approach. Unit costs of individual patient services were applied to health care utilization data. The total costs for mothers and infants of each arm of the trial were not observed to be normally distributed. Therefore, assuming a gamma distribution and a vague prior, the mean cost, standard error, difference of means of both arms of the trial, and a 95% credible interval were estimated using a Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation approach implemented in WinBUGS software.10

To check for potential effect of parity, we estimated the treatment effect and 95% credible intervals for each parity subgroup (0, ≥ 1). In addition, to examine for a treatment-by-parity interaction, the difference in treatment effects and 95% credible intervals were estimated.

The above analysis captures only differences in resource utilization patterns and thus calls for the use of sensitivity analysis to explore the robustness of the results over alternative unit cost values. For the analyses of all women, those with parity equalling zero and those with parity of one or greater, we used the midpoint, low and high unit costs in the analysis to check whether the results were sensitive to the set of unit costs chosen.

To demonstrate which specific services were more costly, depending on the management strategy, we also calculated the average cost per patient for each service provided, by treatment arm, by dividing the total costs of each service by the total number of patients in each treatment arm.

Results

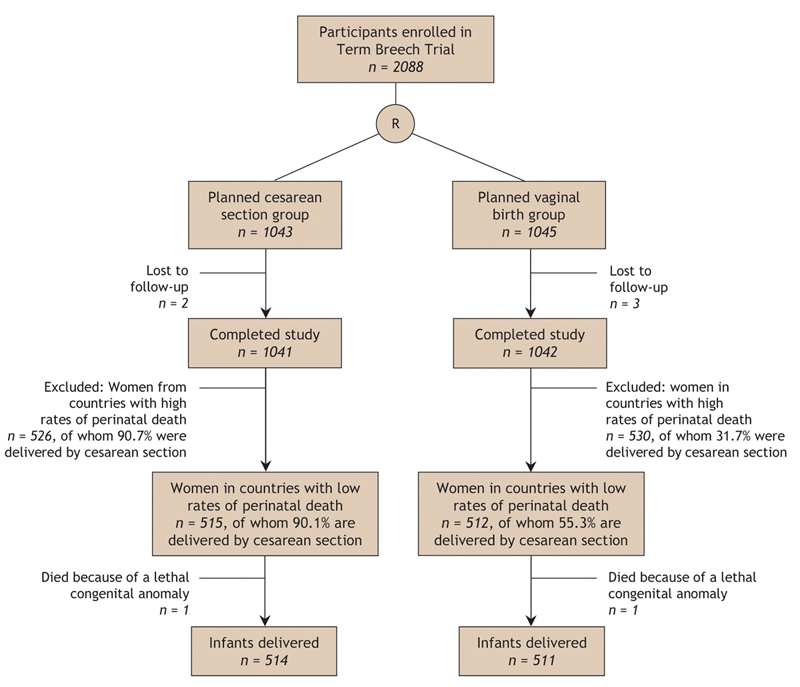

The total number of participants from countries with low national perinatal rates of death was 515 mothers and 514 infants in the planned cesarean group and 512 mothers and 511 infants in the planned vaginal birth group (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Flow of participants through the study. A low national rate of perinatal death is ≤ 20/1000.

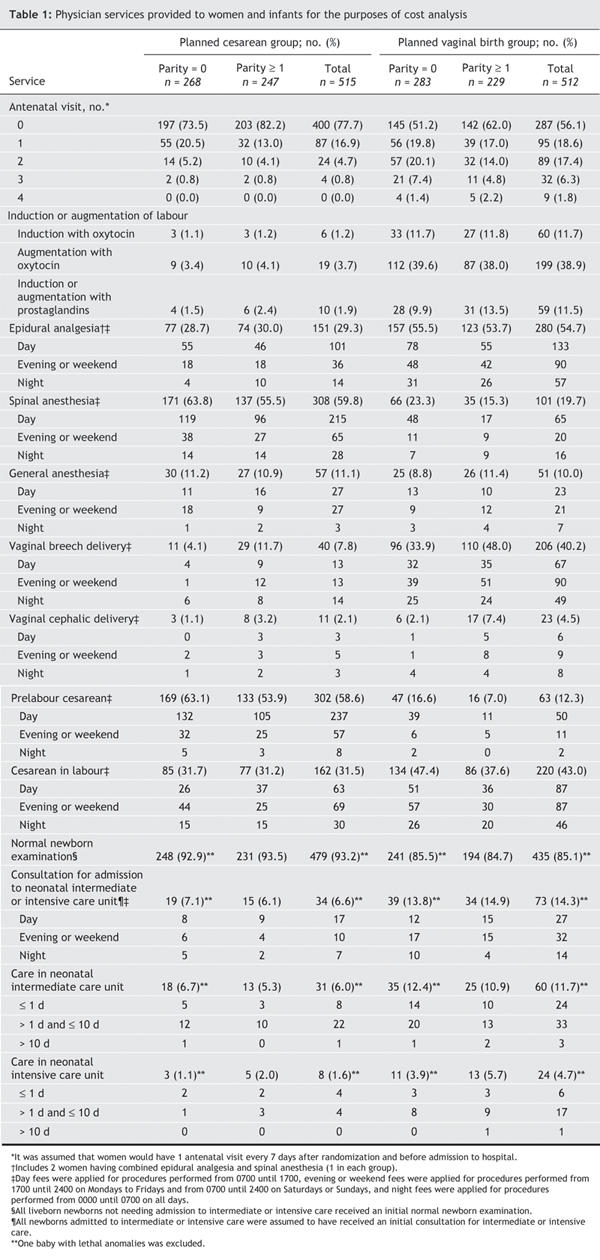

Table 1 shows the physician services provided to women and infants in each arm of the trial. Women in the planned vaginal birth group had more antenatal visits, inductions or augmentations of labour or both with oxytocin, inductions or augmentations of labour or both with prostaglandins, and epidural anesthesia than women in the planned cesarean group. More spinal anesthesia was given in the planned cesarean group. As expected, there were more cesareans in the planned cesarean group and more vaginal breech and cephalic deliveries in the planned vaginal birth group. However, there were more cesareans in labour in the planned vaginal birth group than in the planned cesarean group. Infants in the planned cesarean group were less likely to receive care in the neonatal intermediate care unit or neonatal intensive care unit and more likely to have normal newborn examinations than infants in the planned vaginal birth group.

Table 1

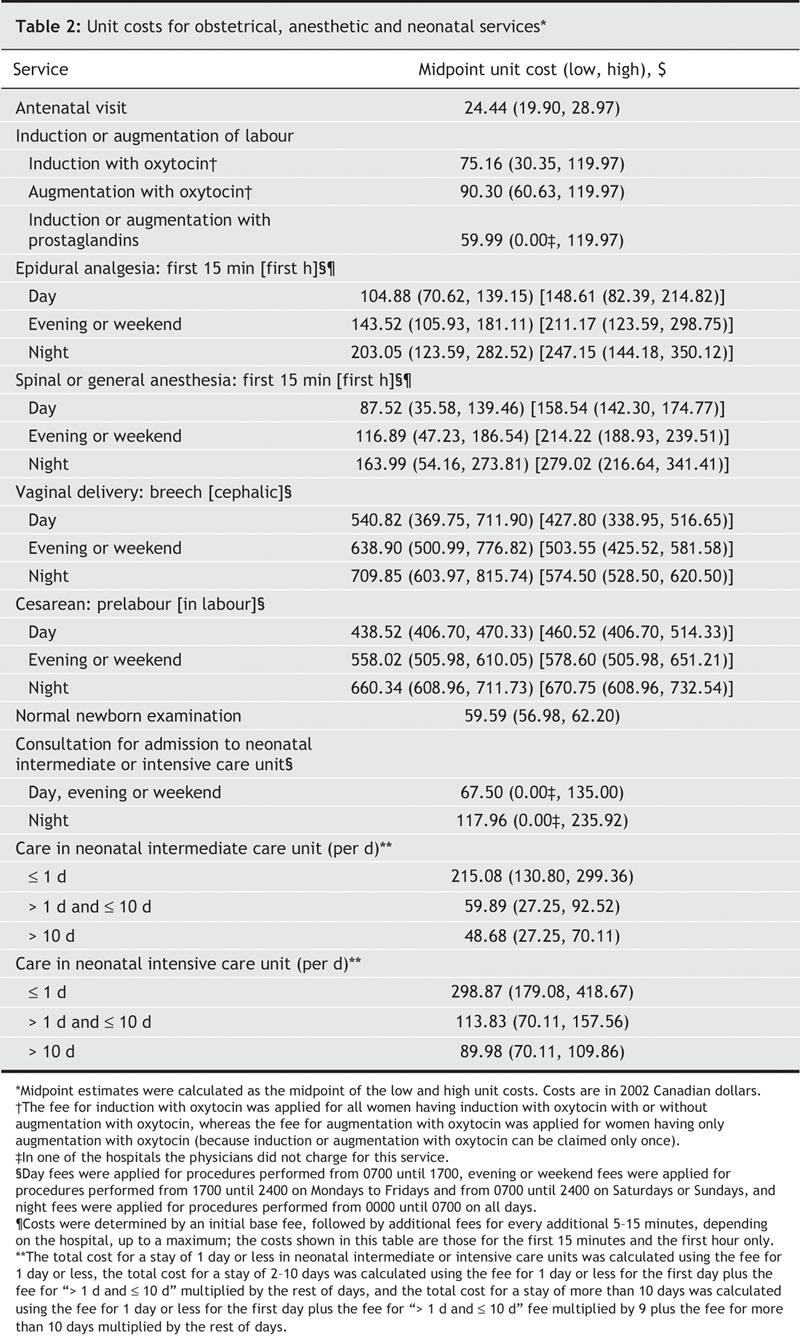

Table 2 presents physician fees (midpoint, low and high) for obstetrical, anesthetic and neonatal services (2002 Canadian dollars). The unit costs of epidural analgesia and spinal and general anesthetic are time dependent. In Table 2 we include only the unit costs at 15 minutes and at the first hour. However, these costs usually rose when the length of time when analgesia or anesthesia were required increased. We further observe that the physician fees for a vaginal breech delivery were higher than for a vaginal cephalic delivery, and that the fees were also higher for a cesarean in labour than a prelabour cesarean. However, the physician fees for a vaginal breech delivery were higher than for either a prelabour cesarean or a cesarean in labour. The variability in unit costs (reflected in the range between low and high estimates) was substantial for high-cost services, such as types of delivery, and was even more substantial for both types of vaginal delivery. Costs were also highly variable for analgesia and anesthesia, and for care provided to infants in the neonatal intermediate care unit and the neonatal intensive care unit.

Table 2

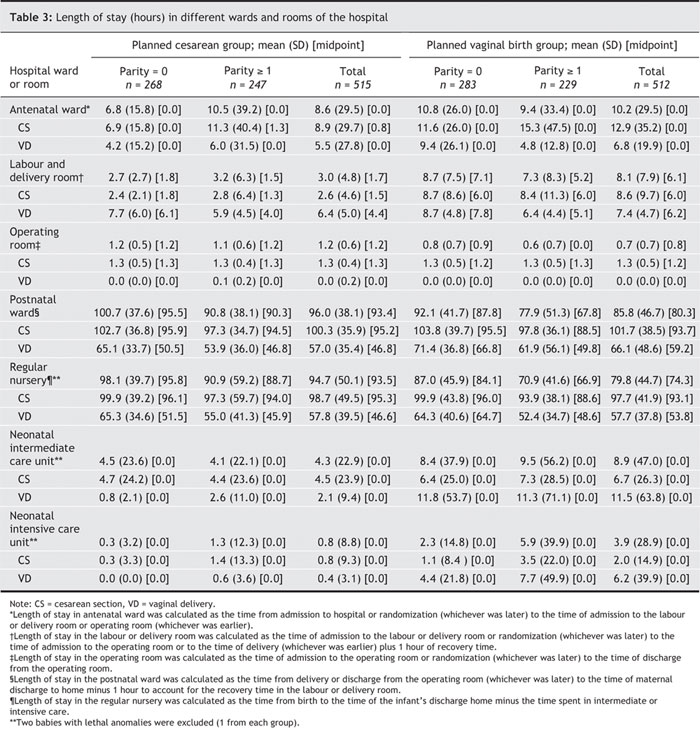

Table 3 shows the lengths of stay in different wards or rooms in the hospital. Women in the planned cesarean group spent, on average, less time in the antenatal ward and in the labour and delivery room than women in the planned vaginal birth group. The mean lengths of stay of women in the planned cesarean group in the operating room and in the postnatal ward were longer than those of the women in the planned vaginal birth group. Infants in the planned cesarean group had a shorter length of stay in the neonatal intermediate and neonatal intensive care units and a longer length of stay in the regular nursery than those in the planned vaginal birth group.

Table 3

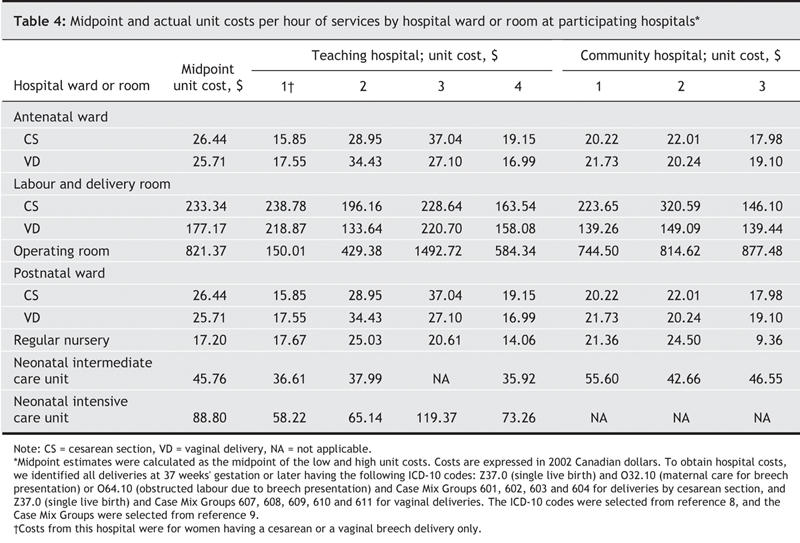

Table 4 presents hospital unit cost estimates per hour (midpoint, low and high, 2002 Canadian dollars). The unit costs per hour of being in the antenatal ward, the labour and delivery room and the postnatal ward were higher for women who delivered by cesarean than for women who delivered vaginally. For the infants, the neonatal intensive care unit had the highest unit cost, followed by the neonatal intermediate care unit and then by the regular nursery because of the intensity of services provided in each level of care. Variability in operating room unit costs was substantial, which reflected the fact that these data were collected from both teaching and community hospitals.

Table 4

The estimated mean cost per patient and its standard error in the 2 groups, and the mean cost difference between the groups and its credible interval, are presented in Table 5. We found that planned cesarean was significantly (i.e., the credible intervals excluded zero) less expensive than planned vaginal birth for the midpoint ($7165 v. $8042), low ($4101 v. $4883) and high ($10 230 v. $11 200) sets of unit costs. Although the treatment effect was largest in the subgroup of women having their first child, there was no statistically significant interaction between treatment and parity, since the 95% credible intervals for the difference in treatment effects between parity equalling zero and parity of one or greater all included zero. The difference between treatment effects was –$697 (95% credible interval –$1508 to $130) for the midpoint unit cost, –$316 (–$798 to $173) for the low unit cost, and –$1080 (–$2237 to $86) for the high unit cost.

Table 5

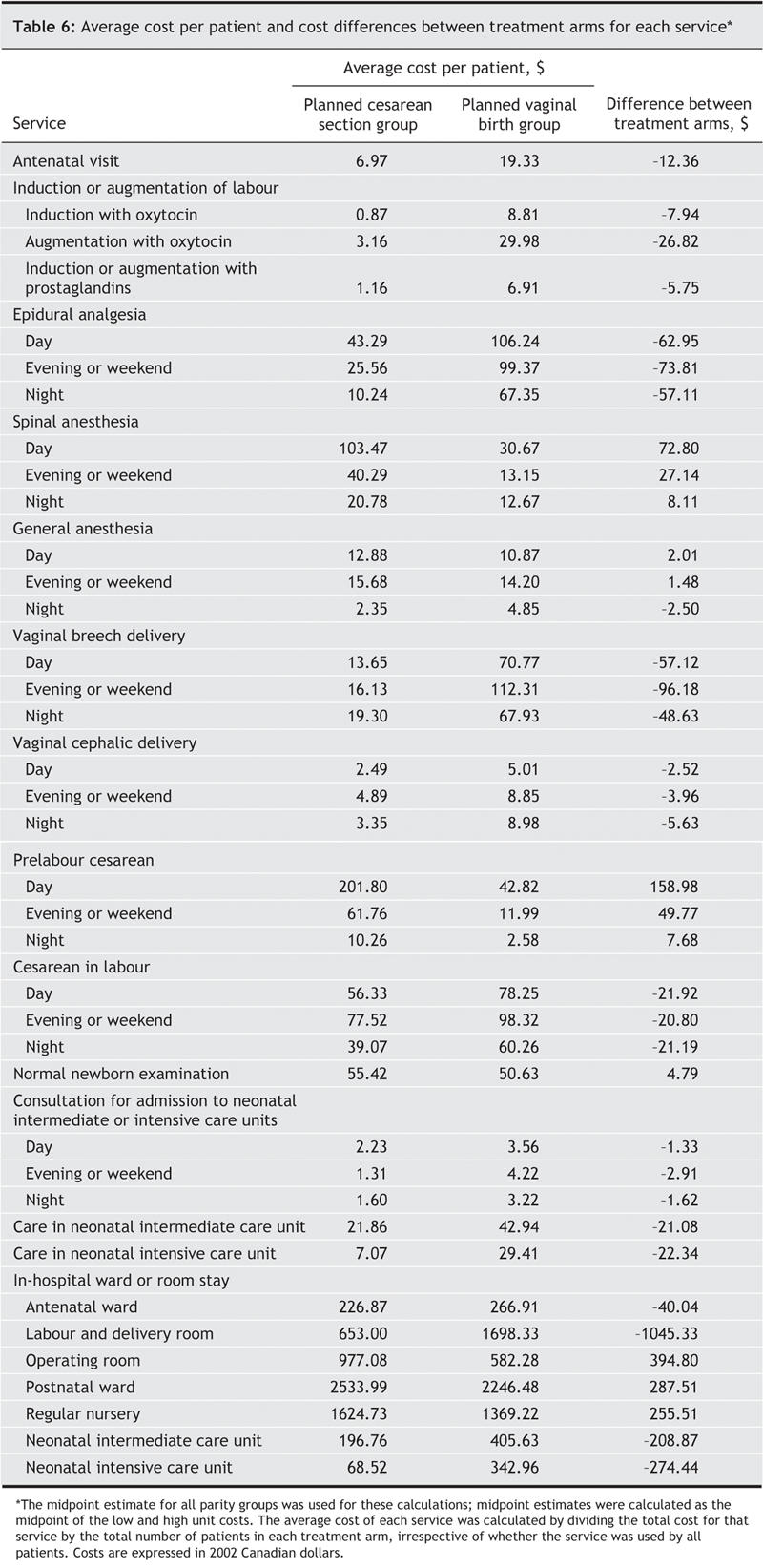

Table 6 presents the average cost per patient for each service by treatment arm. Services with substantially higher costs in the planned cesarean group were the physician fees for a prelabour cesarean and the in-hospital costs of the operating room, postpartum ward and regular nursery. Services with substantially higher costs in the planned vaginal birth group were the physician fees for vaginal breech delivery and epidural analgesia and the in-hospital costs of the labour and delivery room and the neonatal intermediate and intensive care units.

Table 6

Interpretation

In the Term Breech Trial, costs of planned cesareans were lower than those of planned vaginal births, and this did not differ by parity group. Although the planned cesarean group had higher costs for prelabour cesareans, which included the fees for the procedure as well as the in-hospital costs for time in the operating room, the postnatal ward and the normal nursery, women in the planned vaginal birth group spent more time in the labour and delivery suite, and their infants required more care in the neonatal intensive and intermediate care units. Moreover, the fees for a vaginal breech delivery were higher than for a cesarean, and, overall, the planned vaginal birth group incurred more costs for epidural analgesia. The slightly greater cost of the cesareans in labour in the planned vaginal birth group was not a major contributor to the overall differences in costs.

Other cost analyses of planned methods of delivery have also found that the total costs of a planned vaginal birth exceed the cost of an elective cesarean when labour is induced with oxytocin and if epidural anesthesia is also used.11 Other analyses focusing more on a comparison of actual methods of delivery have the opposite results and show that cesarean section costs more than vaginal delivery.12

Our findings might be interpreted as a win–win situation (i.e., planned cesarean is both safer and less expensive than planned vaginal birth in the case of breech presentations at term). However, it would be a misinterpretation of the results of the Term Breech Trial to conclude that the option of planned vaginal birth should no longer be offered to Canadian women. The immediate risks of adverse outcome for the mother are likely somewhat greater with a policy of planned cesarean,13 and some women may continue to prefer to plan a vaginal birth despite the higher risks to the infant. As well, the long-term risks and costs of a policy of cesarean compared with planned vaginal birth, over a lifetime, are not known. For example, this cost analysis did not include the resources used, and their costs, in future pregnancies of the participants.

In summary, using a range of unit costs and resource utilization data from countries with a low rate of perinatal death, we found that planned cesareans cost less than planned vaginal births for women with a singleton fetus in breech presentation at term in the Term Breech Trial. However, these cost savings are restricted to the procedures and care during and immediately following the birth.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Elizabeth Asztalos, Jon Barrett, Sharon Beynon, Peter von Dadleszen, Michèle Dekker, Suzanne Dionne, Joanne Douglas, Linda Greensword, Jean Kronberg, Rosemarie Lourenco, Mark Pearson, Pauline Robertson, Kelly Ross, Peter Rymkiewicz and Filomena Travassos for their assistance with data retrieval and interpretation.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Roberto Palencia contributed substantially to the study's conception and design and to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data and drafted the article. Amiram Gafni, Mary E. Hannah and Sue Ross contributed substantially to the study's conception and design and to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data and revised the article critically for important intellectual content. Andrew R. Willan contributed substantially to the study's conception and design and to the analysis and interpretation of the data and revised the article for important intellectual content. Sheila Hewson and Darren McKay contributed substantially to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data and revised the article critically for important intellectual content. Walter Hannah, Hilary Whyte, Kofi Amankwah, Mary Cheng, Patricia Guselle, Michael Helewa, Ellen D. Hodnett, Eileen K. Hutton, Rose Kung and Saroj Saigal contributed substantially to the study's conception and design and revised the article critically for important intellectual content. All of the authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

This study was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant numbers MT-13884, MT-37415). The Data Co-ordination Centre was supported by grants from The Centre for Research in Women's Health, Sunnybrook and Women's College Health Sciences Centre, and the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Amiram Gafni, Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics (HSC-3H29), McMaster University, 1200 Main St. W., Hamilton ON L8N 3Z5; fax 905 546-5211; gafni@mcmaster.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, et al. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet 2000;356:1375-83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Hewson SA, Weston J, Hannah ME. Crossing international boundaries: implications for the Term Breech Trial Data Coordinating Centre. Control Clin Trials 2002;23:67-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.World Health Organization. Perinatal mortality: a listing of available information. WHO/FRH/MSM/96.7. Geneva: The Organization; 1996.

- 4.Goeree R, Gafni A, Hannah M, et al. Hospital selection for unit cost estimates in multicentre economic evaluations, does the choice of hospitals make a difference? Pharmacoeconomics 1999;15:561-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Schedule of benefits, physician services under the Health Insurance Act. Toronto; 2003.

- 6.Alberta Health and Wellness. Alberta Health Care Insurance Plan, medical procedure list. Edmonton; 2003.

- 7.British Columbia Medical Association. BC Medical Association guide to fees. Vancouver; 2003.

- 8.World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th ed. Geneva; The Organization; 1992–1994.

- 9.Canadian Institute for Health Information. CMG/Plx Directory, ICD-10-CA/CCI Version, 2003. Ottawa; November 2003.

- 10.Spiegelhalter DJ, Thomas A, Best NG. WinBUGS Version 1.4. User Manual. Cambridge: MRC Biostatistics Unit; 2000.

- 11.Bost BW. Caesarean delivery on demand: what will it cost? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003; 188:1418-23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Henderson J, McCandlish R, Kumiega L, et al. Systematic review of economic aspects of alternative modes of delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2001;108:149-57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Hofmeyr J, Hannah ME. Planned cesarean section for breech delivery [Cochrane review]. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1, 2005. Oxford: Update Software.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.