Abstract

Background

The LIM-homeodomain transcription factors LHX7 and LHX6 have been implicated in palatogenesis in mice and thus may also contribute to the incidence of isolated palatal clefts and/or clefts of the lip and primary palate (CL/P) in humans. Causative mutations in the transcription factor IRF6 have also been identified in two allelic CL/P syndromes and common polymorphisms in the same gene are significantly associated with non-syndromal CL/P in different populations.

Results

Here we report the isolation of chick orthologues of LHX7, LHX6 and IRF6 and the first characterisation of their profiles of expression during morphogenesis of the midface with emphasis on the period around formation of the primary palate. LHX7 and LHX6 expression was restricted to the ectomesenchyme immediately underlying the ectoderm of the maxillary and mandibular primordia as well as to the lateral globular projections of the medial nasal process, again underlying the pre-fusion primary palatal epithelia. In contrast, IRF6 expression was restricted to surface epithelia, with elevated levels around the frontonasal process, the maxillary primordia, and the nasal pits. Elsewhere, high expression was also evident in the egg tooth primordium and in the apical ectodermal ridge of the developing limbs.

Conclusion

The restricted expression of both LHX genes and IRF6 in the facial primordia suggests roles for these gene products in promoting directed outgrowth and fusion of the primary palate. The manipulability, minimal cost and susceptibility of chicks to CL/P will enable more detailed investigations into how perturbations of IRF6, LHX6 and LHX7 contribute to common orofacial clefts.

Background

Many genes have been implicated in syndromal and/or non-syndromal cleft lip with or without palate (CL/P). The majority of these candidate genes show expression in the facial ectoderm, including MSX1, BMP4, PVRL1, MID1 and p63, although some (eg. MSX1 and BMP4) also have key roles in the mesenchyme [1]. In addition to coordinating mesenchymal outgrowth, the facial ectoderm also plays a number of other pivotal roles in facial morphogenesis, including facilitating the initial contact of the converging processes and the subsequent elimination of the epithelial seam in a manner that is likely analogous to that which occurs during formation of the more studied secondary palate. Recently, mutations in the IRF6 (Interferon Regulatory Factor 6) gene were shown to cause the allelic disorders, Van der Woude and Popliteal pterygium syndromes, both of which have CL/P as a major clinical feature [2,3]. Significantly, common polymorphisms in IRF6 have also been found to account for up to 12% of the contribution to the high incidence of non-syndromal CL/P, highlighting it as one of the most significant CL/P loci identified to date [4]. Although the exact physiological function of this gene is not known, preliminary findings in mice found that Irf6 is expressed in the medial edge epithelia of the fusing secondary palatal shelves, tooth buds, hair follicles and skin [5]. Surprisingly, however, the expression of IRF6 has not been reported during development and closure of the primary palate, an event which is distinct both in terms of embryological timing and underlying genetics from that of the secondary palate.

Several secreted factors emanating from the facial ectoderm, including fibroblast growth factor 8 (FGF8) and bone morphogenic protein 4 (BMP4) induce mesenchymal expression of genes such as Msx1 and Msx2, that promote mesenchymal cell proliferation and prominence outgrowth [6,7]. Evidence suggests that the mesenchymal LIM-Homeodomain (HD) encoding gene, Lhx7 (also referred to as Lhx8 [8] and L3 [9]), is similarly under the control of ectodermal-derived signals, namely Fgf8 [10-13]. In the mouse, Lhx7 and its close homologue, Lhx6, were reported to be expressed only in the maxillary and rostral mandibular processes, palatal shelves and basal forebrain [9,10,14]. In Lhx7-knockout mice, an isolated secondary palatal cleft was the only reported feature: the secondary palatal shelves formed and elevated normally but failed to properly contact and fuse [15]. Of note however, is that most inbred mouse strains rarely display lateral facial clefts analogous to CL/P in humans. This is probably due in part to the altered growth rates that give rise to the elongated facial morphology although differences in sensitivity to gene dosage or redundancies between related genes may also play a role [1]. Consistent with this, mutations in MSX1 in humans are associated with clefts of the primary palate whereas knockout of both Msx1 and Msx2 are required to produce a primary palate cleft in mice [16]. In contrast, the chick in some ways provides a more suitable model system for studies on primary palatal clefting as this species, like humans, shows greater susceptibility to this anomaly. Here, we have isolated chick cDNAs orthologous to human IRF6, LHX7 and LHX6 and investigated their profile of expression during morphogenesis of the midface with an emphasis on the period around formation of the primary palate.

Results

Sequence conservation of LHX7, LHX6 and IRF6 between chick, mouse and human

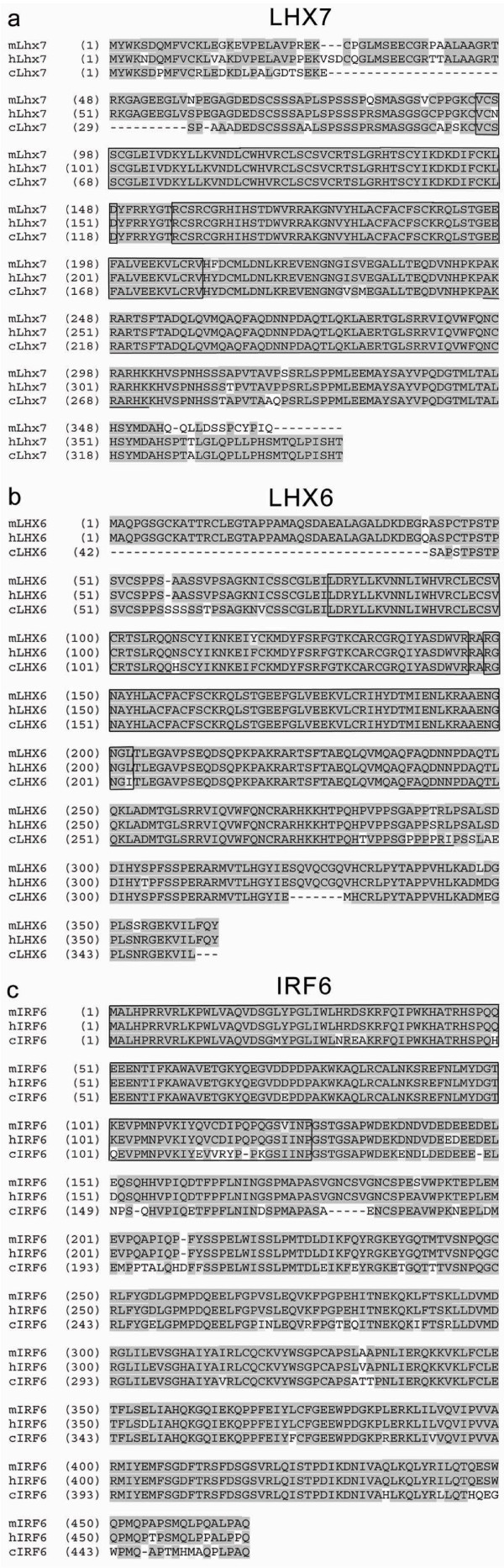

cLHX7: chEST766i11 was shown to encode a protein with 89% and 95% identity to mouse and human Lhx7/LHX7, respectively (Fig 1a). cLHX6: chEST365j8 represented a partial sequence (708 bp) encoding two LIM domains and the 5' end of a HD which displayed 94% identity (99% similarity) to both human and mouse LHX6/Lhx6 (Fig 1b). cIRF6: chEST58f7 represented a partial sequence of 1665 bp that encoded the C-terminal two thirds (304 amino acids) with 83% identity (99% similarity) to human and mouse IRF6/Irf6 (Fig 1c).

Figure 1.

Protein alignments of mouse, chick and human LHX7 (a), LHX6 (b) and IRF6 (c). cLHX7 displays 89% and 95% identity with mouse Lhx7 and human LHX7, respectively. cLHX6 displays 94% identity and 99% similarity to both human LHX6 and mouse Lhx6. cIRF6 displays 83% identity, 99% similarity with human IRF6 and mouse Irf6. Legend: The LIM domains of LHX6/7 and DNA-binding domain of IRF6 are boxed. The homeodomain of LHX6/7 is underlined.

Expression of cLHX6 and cLHX7 in the facial primordia

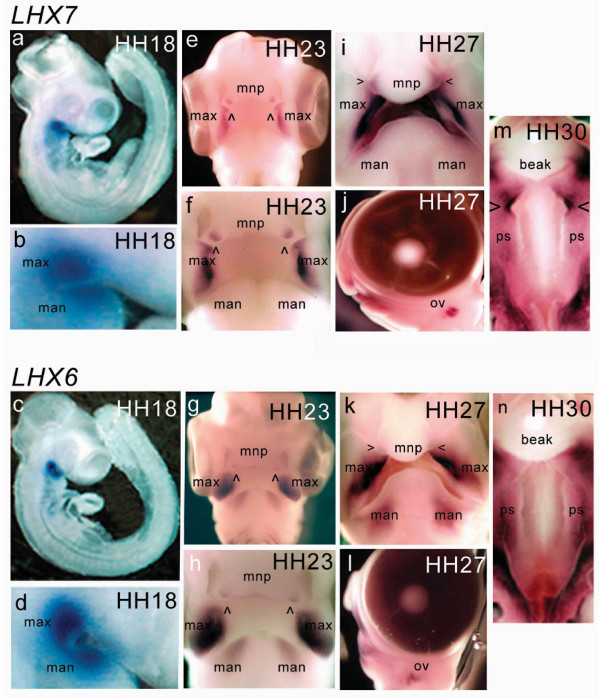

cLHX6 and cLHX7 expression was initially detected by whole-mount in situ hybridization at Hamburger-Hamilton stage (HH)15 and remained detectable up to HH30 (Fig 2). Strong expression was found ventrally along the length of the maxillary primordia and the rostral portion of the mandibular primordia. Maxillary expression remained high post-fusion with the medial nasal process (Fig 2a–i, k). In the mandibular primordia, cLHX6 expression remained strong whereas cLHX7 appeared to gradually diminish from stage HH23. Of note, expression of both cLHX7 and cLHX6 was also detected in mesenchyme immediately underlying the pre-fusion epithelia of the globular projections of the medial nasal process from HH22 (arrowheads in Fig 2e, f, g, h). cLHX7 expression was far more pronounced than cLHX6 in this region and remained detectable in the mesenchymal bridge of the beak up to HH30, albeit at a much lower level (not shown). Vibratome sections of these embryos revealed that expression of cLHX7 and cLHX6 was restricted to ectomesenchyme directly subjacent to the facial ectoderm (Fig 3). This expression profile resembles in part that of the Wnt inhibitor, Dkk1 [17] and is consistent with the evidence indicating Lhx7 and Lhx6 are under the regulation of signals emanating from the ectoderm [12,18,19]. Expression of both genes was also detected later in the palatal shelf mesenchyme at HH30 (Fig 2m, n), with cLHX7 uniquely displaying strong expression on the anterior tips of the developing shelves. Expression of both cLHX7 and cLHX6 was also detected in the basal forebrain (data not shown) and the otic vesicle from HH25 to HH30 (Fig 2j, l).

Figure 2.

Expression pattern of cLHX7 and cLHX6 in the developing chick embryo. cLHX7 (top panel) and cLHX6 (bottom panel) were restricted to the ventral extremities of the maxillary primordia and the rostral tip of the mandibular primordia before and after fusion of the maxillary primordia and medial nasal process during formation of the primary palate (a – i, k). From around HH27, cLHX6 expression was dispersed throughout the mandibular primordia (k). cLHX7 and cLHX6 expression was detected in the pre-fusion zone of the medial nasal process, prior to fusion with the maxillary primordia (e, f, g, h). The expression in the medial nasal process remained in the mesenchymal bridge of the beak after fusion (i, k). cLHX7 and cLHX6 expression was detected in the mesenchyme throughout the palatal shelves at HH30 (m, n). cLHX7 specifically displayed increased expression on the anterior tips of the developing shelves (m). Both cLHX7 and cLHX6 expression was detected in the otic vesicle from HH25 to HH30 (j, l). Abbreviations: max: maxillary primordia; man: mandibular primordia; mnp: medial nasal process; ov: otic vesicle; ps: palatal shelves.

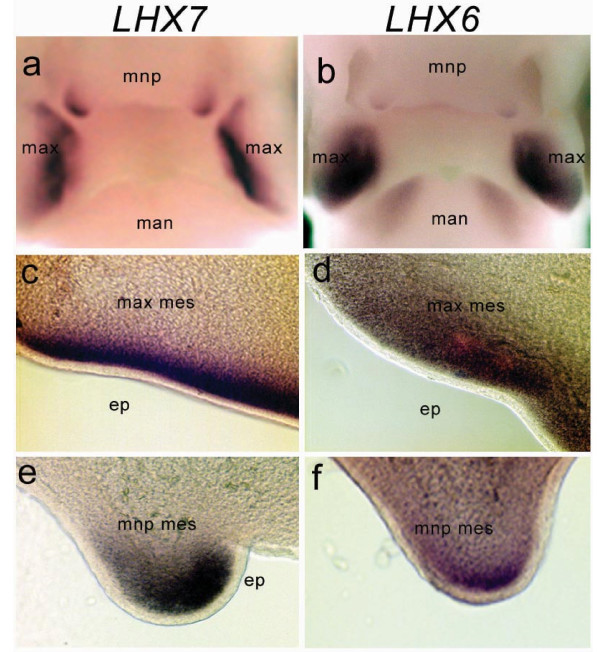

Figure 3.

Vibratome sections of whole-mount in situ hybridization embryos. Sectioning of stage HH23 whole mount in situ hybridization embryos indicates that both LHX7 (left column) and LHX6 (right column) show expression in the neural crest-derived mesenchyme of the first branchial arch (maxillary primordia shown) (c, d) and the lateral globular masses at the edges of the medial nasal process (e, f) restricted to the region directly subjacent to the ectoderm. Abbreviations: max mes: maxillary primordia mesenchyme; ep: epithelium; mnp: medial nasal process

Expression of cIRF6 in HH20-29 embryos

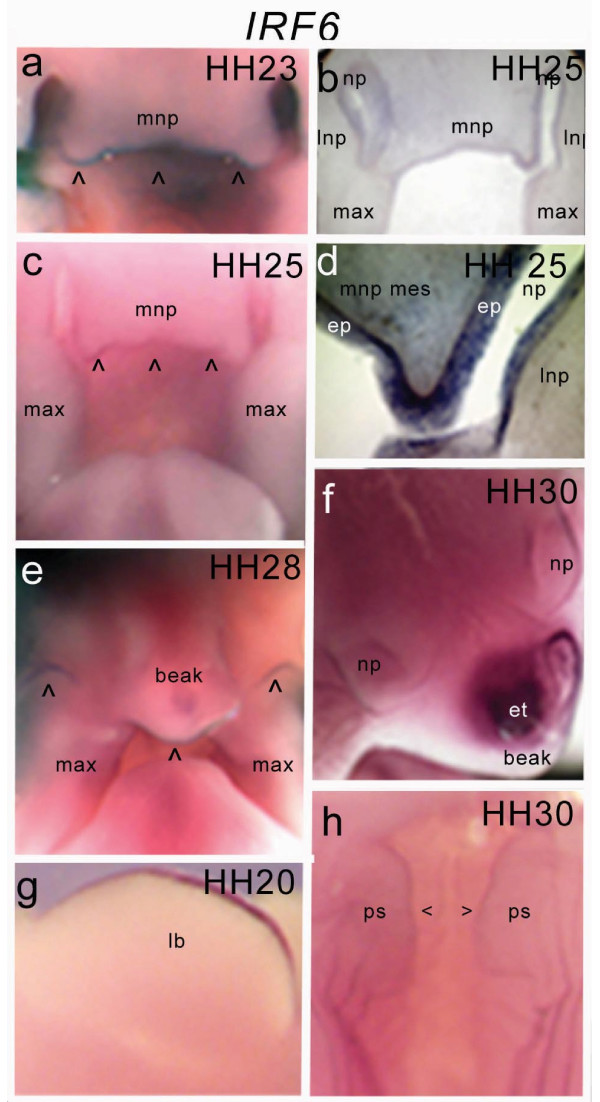

cIRF6 expression was detected by whole-mount in- situ hybridization throughout the ectoderm of the craniofacial structures of HH20-29 embryos (Fig 4). Vibratome sections of whole-mount embryos revealed IRF6 levels generally very low but were elevated in the epithelia covering the frontonasal process, the maxillary primordia, and the nasal pits (Fig 4b, d). Expression in the leading edges of the medial nasal process, which ultimately fuse with the maxillary primordia during formation of the primary palate, disappeared with the elimination of epithelia and formation of the mesenchymal bridge. cIRF6 expression was also detected in the ectoderm of the leading edges of the developing palatal shelves as well as in the ridges of the primitive oral cavity at HH29 (Fig 4h). High cIRF6 expression was also detected in the apical ectodermal ridge of the limb buds (Fig 4g). Notably, expression was also very high in the egg tooth primordium from HH27 (Fig 4f).

Figure 4.

Expression of IRF6 in the developing chick embryo. Expression is restricted to facial ectoderm. Whole-mount in situ hybridisation (a, c, e) and vibratome sections of whole-mount embryos (b, d) revealed notable IRF6 expression in the epithelia surrounding the frontonasal process, the maxillary primordia, and the nasal pits. IRF6 expression was also detected in the ectoderm of the leading edges of the palatal shelves and in the ridges of the primitive oral cavity at HH30 (h). High IRF6 expression was also found in the apical ectodermal ridge of the limb buds (g) and in the egg tooth primordium (f).

Discussion

Here we have isolated the chick orthologues of LHX7, LHX6 and IRF6 and shown a high degree of sequence conservation with their mouse and human counterparts, suggesting evolutionary conserved functions for these proteins. It should be noted that despite repeated attempts at amplification of mRNA/cDNA across the equivalents of exons 1 to 3 and analysis of available chick genomic sequence, cLHX7 did not contain the equivalent of human and mouse exon 2. As this exon does not encode a known functional domain and its absence maintains the reading frame, it is likely that cLHX7 also encodes a functional LIM-HD transcription factor. Interestingly, compared to the mouse, chick and human LHX7 had an additional 4 bp in the last coding exon producing a C-terminus with an additional nine amino acids. The validity of the mouse Lhx7 sequence over this region was confirmed by sequencing murine (Swiss) genomic DNA. That the additional 4 bp is also evident in rat LHX7 indicates this 4 bp deletion likely represents a recent evolutionary event that may be restricted to the murine lineage. The biological significance of this must await determination.

In order to determine whether the chick would provide an appropriate model with which to investigate the roles of LHX7, LHX6 and IRF6 in craniofacial development and CL/P, their respective expression patterns around the time of primary palate morphogenesis were determined. Similarly to the mouse, cLHX7 and cLHX6 were expressed in ectomesenchyme of the maxillary and mandibular primordia [9,10] although in contrast to the mouse, the mandibular expression of cLHX7 was not prominent. Differential expression of cLHX7 and cLHX6 in the mandibular primordia was also evident at the anterior tips of the palatal shelves suggesting thee two genes are under distinct regulatory control which is consistent with results from Cre-mediated Fgf8-knockout mice [11] in which Lhx7 but not Lhx6 expression was lost.

Of particular interest, our expression studies in the chick have identified unique LHX7 and LHX6 expression domains. We detected strong cLHX7 and cLHX6 expression in the mesenchyme immediately underlying the pre-fusion epithelia of the medial nasal process, from around HH22, which remained in the mesenchymal bridge post fusion. This expression has not previously been reported for the mouse and importantly suggests a role for LHX7 and LHX6 in outgrowth/survival of the medial nasal process during formation of the primary palate. cLHX7 and cLHX6 expression was also detected in the otic vesicle (from HH25 to HH30) a site of expression also not been reported in mice or any other species and therefore may be unique to the chick.

The strong expression in maxillary and medial nasal mesenchyme subjacent to the pre- and post fusion ectoderm indicate that LHX7 and LHX6 would be good candidate genes for craniofacial anomalies, in particular CL/P despite the isolated secondary palate cleft in Lhx7 knock-out mice. In this regard, hLHX7 localizes to chromosome 1p31-4 (and not 4q as previously suggested [20]) and is found less than 1.4 Mb from marker D1S1665 which showed the most significant linkage in one cohort of non-syndromal CL/P cases [20]. In fact, this same region produced the only positive lod score for an individual Finnish family presenting with Van der Woude syndrome-like features [21]. These data and the results reported herein put forward a case for screening patients with non-syndromal CL/P or IRF6 mutation negative Van der Woude syndrome for mutations in LHX7.

IRF6 is mutated in Van der Woude and Popliteal pterygium syndromes [2,3] and has recently been identified as one of the most significant non-syndromal CL/P loci to date [4]. This report is the first to describe IRF6 expression in the facial primordia prior to and during morphogenesis of the primary palate and supports the notion of a primary ectodermal defect in patients harboring mutations in IRF6. In concordance with the later embryonic stages assessed in the mouse [5], cIRF6 was similarly detected in the leading edge ectoderm of the palatal shelves and the ridges of the primitive oral cavity in the chick. Interestingly, we also detected some unique expression domains of IRF6, which may be specific to the chick. Strong IRF6 expression was detected in the egg tooth primordium indicating it as an excellent marker for this structure. Like other genes that are expressed in the ectoderm of the developing face such as SHH and BMP4 [22,23], high IRF6 expression was also detected in the apical ectodermal ridge of the limb buds, which is consistent with the presence of limb hypoplasia or agenesis of digits, syndactyly, as well as valgus or varus deformities of the feet seen in Popliteal pterygium syndrome [24].

Conclusion

The data presented herein shows both highly conserved and unique temporal and spatial expression of LHX7, LHX6 and IRF6 in the chick, particularly in the facial primordia around the time of their fusion to form the primary palate. The manipulability, minimal cost and susceptibility of chicks to CL/P will enable more detailed investigations into the functions of these genes in midfacial development and their role in contributing to common orofacial clefts.

Methods

Isolation of cLHX7, cLHX6 and cIRF6

Full-length murine Lhx7, Lhx6 and Irf6 cDNAs (Genbank: AJ000338, AB031040, NM_016851, respectively) were used to BLAST the BBSRC chick expressed sequenced tag (EST) database [25]. Clones that displayed a high degree of homology were purchased from MRC GeneService (Cambridge, UK) then purified and completely sequenced using vector primers. Automated DNA sequencing was performed by cycle sequencing with Applied Biosystems Dye Terminator chemistry v3. cDNA sequences and predicted amino acid analyses and alignments were performed locally using Vector NTI and via the internet using BLAST at NCBI [26]. Primers used to amplify and sequence mLhx7 exons 6–9 were as follows: mLx7ex6-9f: 5'-TGA-AGA-GAG-AAG-TGG-AGA-ACG-3'; mLx7ex6-9f: 5'-TGG-GCA-AGA-GGA-TGT-TC-3'.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization on chick embryos

Fertilized chicken eggs were purchased from HiChick (Gawler, South Australia) and incubated at 36°C, 80% humidity for the appropriate times. Embryos were staged according to Hamburger and Hamilton [27]. Embryos were dissected from the eggs in cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS either at room temperature for 2 hours or overnight at 4°C and then dehydrated through a series of increasing methanol/PBT (PBS + 0.1% Triton X) washes [28]. For whole-mount in situ hybridization, digoxygenin-labeled sense and anti-sense RNA probes were generated by in vitro transcription as follows: cLHX7: a 1.2 kb HindIII fragment from chick EST 766i11 (chEST766i11) was subcloned into appropriately restricted pBluescript and the resultant plasmid linearised using NotI (antisense) and ClaI (sense) and transcribed using T3 and T7 polymerases, respectively. cLHX6: the 709 bp chEST365j8 was linearised using NotI (anti-sense) and HindIII (sense) and transcribed using T3 and T7 polymerases, respectively. cIRF6: chEST58f7 was digested with SacI and subcloned into pBluescript. The resultant 889 bp fragment linearised with MscI (antisense) and EcoRI (sense) and transcribed using T3 and T7 polymerases, respectively. Hybridisation, washes and probe detection were carried out on whole or dissected chick embryos from HH 10–30 according to Xu and Wilkinson [28]. Post-hybridisation, HH23, 27 and 30 chick embryos were fixed in 4% PFA, embedded in 7% low melting agarose (Sigma A2576) and sectioned with a vibratome to a thickness of 100μm. All chick embryo work was reviewed and approved by the University of Adelaide Animal Ethics Committee.

Authors' contributions

BJW participated in the design of the study, carried out all described experiments and drafted the manuscript. TCC conceived, designed and coordinated the study, advised on protein alignments, and helped draft the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Note added in proof

During review of our article, a study by Inoue et al (Inoue M, Kawakami M, Tatsumi K, Manabe T, Makinodan M, Matsuyoshi H, Kirita T, Wanaka A. Expression and regulation of the LIM homeodomain gene L3/Lhx8 suggests a role in upper lip development of the chick embryo. Anat Embryol. 2006 Epub ahead) was published that similarly reported restricted mesenchymal expression of chick LHX7 and demonstrated that it, like its murine counterpart, appears to be under the regulatory control of epithelial signals including FGF8.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The chick sequences reported herein have been deposited in GenBank: cLHX7 (nucleotide – DQ082893; protein – AAZ41374), cLHX6 (nucleotide – DQ082894; protein – AAZ30032) and cIRF6 (nucleotide – DQ250733; protein – ABB77237). BJW is a recipient of an Australian Postgraduate Research Scholarship. This work was supported in part by the ARC Special Research Centre for the Molecular Genetics of Development.

Contributor Information

Belinda J Washbourne, Email: belinda.luciani@adelaide.edu.au.

Timothy C Cox, Email: timothy.cox@med.monash.edu.au.

References

- Cox TC. Taking it to the max: The genetic and developmental mechanisms coordinating midfacial morphogenesis and dysmorphology. Clin Genet. 2004;65:163–176. doi: 10.1111/j.0009-9163.2004.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghassibé M, Revencu N, Bayet B, Gillerot Y, Vanwijck R, Verellen-Dumoulin C, Vikkula M. Six families with van der Woude and/or popliteal pterygium syndrome: all with a mutation in the IRF6 gene. J Med Genet. 2004;41:e15. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.009274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatta V, Scarciolla O, Cupaioli M, Palka C, Chiesa PL, Stuppia L. A novel mutation of the IRF6 gene in an Italian family with Van der Woude syndrome. Mutat Res. 2004;547:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucchero TM, Cooper ME, Maher BS, Daack-Hirsch S, Nepomuceno B, Ribeiro L, Caprau D, Christensen K, Suzuki Y, Machida J, Natsume N, Yoshiura K, Vieira AR, Orioli IM, Castilla EE, Moreno L, Arcos-Burgos M, Lidral AC, Field LL, Liu YE, Ray A, Goldstein TH, Schultz RE, Shi M, Johnson MK, Kondo S, Schutte BC, Marazita ML, Murray JC. Interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6) gene variants and the risk of isolated cleft lip or palate. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:769–780. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S, Schutte BC, Richardson RJ, Bjork BC, Knight AS, Watanabe Y, Howard E, de Lima RL, Daack-Hirsch S, Sander A, McDonald-McGinn DM, Zackai EH, Lammer EJ, Aylsworth AS, Ardinger HH, Lidral AC, Pober BR, Moreno L, Arcos-Burgos M, Valencia C, Houdayer C, Bahuau M, Moretti-Ferreira D, Richieri-Costa A, Dixon MJ, Murray JC. Mutations in IRF6 cause Van der Woude and popliteal pterygium syndromes. Nat Genet. 2002;32:285–289. doi: 10.1038/ng985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman JM, Lee SH. About face: signals and genes controlling jaw patterning and identity in vertebrates. Bioessays. 2003;25:554–568. doi: 10.1002/bies.10288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis-West PH, Robson L, Evans DJ. Craniofacial development: the tissue and molecular interactions that control development of the head. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 2003;169:III–VI, 1-138. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-55570-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitanaka J, Takemura M, Matsumoto K, Mori T, Wanaka A. Structure and chromosomal localization of a murine LIM/homeobox gene, Lhx8. Genomics. 1998;49:307–309. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Tanaka T, Furuyama T, Kashihara Y, Mori T, Ishii N, Kitanaka J, Takemura M, Tohyama M, Wanaka A. L3, a novel murine LIM-homeodomain transcription factor expressed in the ventral telencephalon and the mesenchyme surrounding the oral cavity. Neurosci Lett. 1996;204:113–116. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriou M, Tucker AS, Sharpe PT, Pachnis V. Expression and regulation of Lhx6 and Lhx7, a novel subfamily of LIM homeodomain encoding genes, suggests a role in mammalian head development. Development. 1998;125:2063–2074. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.11.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trumpp A, Depew MJ, Rubenstein JL, Bishop JM, Martin GR. Cre-mediated gene inactivation demonstrates that FGF8 is required for cell survival and patterning of the first branchial arch. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3136–3148. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.23.3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker AS, Al Khamis A, Ferguson CA, Bach I, Rosenfeld MG, Sharpe PT. Conserved regulation of mesenchymal gene expression by Fgf-8 in face and limb development. Development. 1999;126:221–228. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker AS, Yamada G, Grigoriou M, Pachnis V, Sharpe PT. Fgf-8 determines rostral-caudal polarity in the first branchial arch. Development. 1999;126:51–61. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Mori T, Takaki H, Takeuch M, Iseki K, Hagino S, Murakawa M, Yokoya S, Wanaka A. Comparison of the expression patterns of two LIM-homeodomain genes, Lhx6 and L3/Lhx8, in the developing palate. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2002;5:65–70. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0544.2002.02198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Guo YJ, Tomac AC, Taylor NR, Grinberg A, Lee EJ, Huang S, Westphal H. Isolated cleft palate in mice with a targeted mutation of the LIM homeobox gene lhx8. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:15002–15006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashique AM, Fu K, Richman JM. Endogenous bone morphogenetic proteins regulate outgrowth and epithelial survival during avian lip fusion. Development. 2002;129:4647–4660. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong SG, Gong TW, Shum L. Identification of markers of the midface. J Dent Res. 2005;84:69–72. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CA, Tucker AS, Sharpe PT. Temporospatial cell interactions regulating mandibular and maxillary arch patterning. Development. 2000;127:403–412. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.2.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobourne MT, Sharpe PT. Tooth and jaw: molecular mechanisms of patterning in the first branchial arch. Arch Oral Biol. 2003;48:1–14. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9969(02)00208-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marazita ML, Field LL, Cooper ME, Tobias R, Maher BS, Peanchitlertkajorn S, Liu YE. Genome scan for loci involved in cleft lip with or without cleft palate, in Chinese multiplex families. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:349–364. doi: 10.1086/341944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koillinen H, Wong FK, Rautio J, Ollikainen V, Karsten A, Larson O, Teh BT, Huggare J, Lahermo P, Larsson C, Kere J. Mapping of the second locus for the Van der Woude syndrome to chromosome 1p34. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9:747–752. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RA, Hu D, Helms JA. From head to toe: conservation of molecular signals regulating limb and craniofacial morphogenesis. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;296:103–109. doi: 10.1007/s004410051271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan BL. Bone morphogenetic proteins in development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:432–438. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(96)80064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasidharan CK, Ravi KV. Popliteal pterygium syndrome with unusual features. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:269–270. doi: 10.1007/BF02724282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BBSRC Chick Expressed Sequenced Tag (EST) Database http://www.chick.umist.ac.uk

- National Center for Biotechnology Information http://www.ncbi.nih.gov

- Hamburger V, Hamilton HL. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. J Morph. 1951;88:49–92. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1050880104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Wilkinson DG. In situ hybridisation of mRNA with hapten labelled probes. In: Wilkinson DG, editor. In Situ Hybridisation: A Practical Approach. 2nd. Oxford, Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]