Abstract

During the routine impurity profile of lisinopril bulk drug by HPLC (high-performance liquid chromatography), a potential impurity was detected. Using multidimensional NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) technique, the trace-level impurity was unambiguously identified to be 2-(-2-oxo-azocan-3-ylamino)-4-phenyl-butyric acid after isolation from lisinopril bulk drug by semi-preparative HPLC. Formation of the impurity was also discussed. To our knowledge, this is a novel impurity and not reported elsewhere.

Keywords: Lisinopril, Impurity, Structural characterization, NMR

INTRODUCTION

Lisinopril is a lysine analog of enalaprilat, the active metabolite of enalapril and is a long-acting, nonsulfhydryl angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor that used for treating hypertension and congestive heart failure (Lancaster and Todd, 1988; Goa et al., 1996; Simpson and Jarvis, 2000). The impurity profile of a drug substance is critical to its safety assessment, is important for monitoring manufacturing process, and it is a stringent regulation that all impurities at level ≥0.1% should be identified (Krishna Reddy et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2005; Cao et al., 2005). Presently, structural identification is difficult as these compounds represent low-level components of a mixture. In this study, a trace-level impurity in the bulk drug of lisinopril was analyzed using multidimensional NMR technique to identify the structure.

EXPERIMENTAL DETAILS

Materials

The bulk drug of lisinopril under investigation was obtained from Zhejiang Huahai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. (Taizhou, China). HPLC (high-performance liquid chromatography) grade methanol and acetonitrile were obtained from Merk Co. (Darmstadt, Germany) and water was purified using a Milli-Q purification system (Millipore, Bedford, USA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

Analytical HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1100 series HPLC system. A Waters Symmetry C18 column (4.6 mm×150 mm, 5 μm, Waters) was used for the separation. The mobile phase was a mixture of acetonitrile and buffer (1:9, v/v), and buffer consisting of 20 mmol/L KH2PO4 adjusted with KOH to pH 4.9. The flow rate was set at 0.8 ml/min, and detection was carried out at 210 nm wavelength. A ZORBAX C18 column (9.4 mm×250 mm, 5 μm, Agilent) was used for the semi-preparation on a Waters 600 HPLC system. The mobile phase consisted of methanol and water (1:9, v/v) at flow rate of 3.0 ml/min.

Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FTICRMS)

High resolving power and accuracy mass measurements were performed on a Bruker APEXIII 7.0T FTICR mass spectrometer (Billerica, MA, USA) equipped with an Apollo ESI source to obtain the element composition of target impurity.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy

1D (1H NMR, 13C NMR) and 2D (1H-1H COSY, DEPT135, HMQC, HMBC) NMR experiments were performed on a Bruker Advance DMX 500 instrument with a quadranuclear probe (QNP) head at ambient temperature, using D2O as solvent. The data were acquired on silicons graphics O2 workstations using XWINNMR version 2.1 (Bruker Analytik, GmbH, Germany).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Detection and isolation

Seven batches of bulk drug were analyzed by analytical HPLC, and potential impurity at a level 0.05% to 0.3% based on HPLC peak area percentage was detected. A typical HPLC chromatogram was recorded (Fig.1). The target impurity was isolated by semi-preparative HPLC. Then the collected fraction was concentrated under high vacuum on a Buchi Rotavapor Model R250 to dryness for further NMR experiments to generate spectral data.

Fig. 1.

HPLC chromatogram of bulk lisinopril drug

Structural elucidation

The target impurity was isolated as white powder. Its molecular formula was determined to be C16H22N2O3 by FTICRMS (m/z 291.1719 [M+H]+, calcd 291.1703). The FT-IR spectrum exhibited a characteristic stretching absorption band at 3448 cm−1 indicating the presence of NH group. And the strong C=O stretching (amide band-I) and bending (amide band-II) bands at 1670 and 1541 cm−1 indicated the presence of amide group. In addition, strong adsorption band attributed to benzene ring at 1627 cm−1 was observed. These adsorption bands clearly indicated the presence of C=O, NH, benzene ring groups, etc. in the molecular structure of impurity.

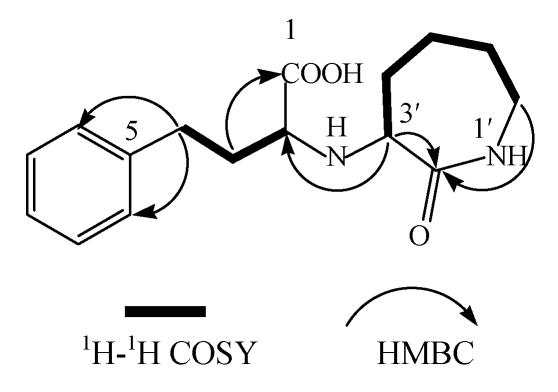

The 1H and 13C NMR spectra, together with data from DEPT and HMQC experiments, revealed the presence of six methylenes (C-3, C-4, C-4′, C-5′, C-6′, C-7′), five sp2-hybridized methines (C-6, C-7, C-8, C-9, C-10), two sp3-hybridized methines (C-2, C-3′) and three quaternary sp2-carbons (C-1, C-5, C-2′) (Table 1). The presence of mono-substituted benzene ring in the 1H NMR spectrum was indicated by the proton signals at δ 7.30 (2H, m, H-6, H-10), 7.23 (2H, m, H-7, H-9), 7.19 (1H, m, H-8), with corresponding carbon signals at δ 130.3, 129.9, 128.0 (Table 1). In the up-field region, 1H-1H COSY spectrum defined two spin systems: one involving two methylenes and a methine group at δ 3.60 (1H, t, J=5.8 Hz, H-2), 2.68 (2H, m, H-4), 2.12 (2H, m, H-3), and the other involving four methylenes and a methine group at δ 1.70 (1H, m, H-4′), 2.10 (1H, m, H-4′), 1.97 (1H, m, H-5′), 1.64 (1H, m, H-5′), 1.75 (1H, m, H-6′), 1.28 (1H, m, H-6′), 3.16 (2H, m, H-7′) and 4.05 (1H, d, J=10.3, H-3′). In the HMBC spectrum, long-range correlations between δ 3.16 (H-7′) and δ 174.1 (C-2′), together with their chemical shifts, indicated that both C-2′ and C-7′ were connected to the same nitrogen atom. Further, 3J correlations between δ 2.12 (H-3) and δ 174.7 (C-1), δ 2.68 (H-4) and δ 129.9 (C-6, C-10), unambiguously determined the positions of the carboxyl group at C-1 and the mono-substituted benzene group (Fig.2). In addition, cross peaks were observed between δ 4.05 (H-3′) and δ 174.1 (C-2′), δ 64.0 (C-2) in the HMBC spectrum. Taking into consideration the chemical shifts of H-3′ and H-2, the positions of C-3′ and C-2 were proposed (Fig.2). Based on the above evidence, the structure of the target impurity was identified as 2-(2-oxo-azocan-3-ylamino)-4-phenyl-butyric acid. To our knowledge, this is a novel compound and not reported anywhere.

Table 1.

1D and 2D NMR data for target impurity (500/125 MHz, D2O)

| C/H | δH | δC | DEPT | HMBC |

| 1 | / | 174.7 | C | H-2, H-3 |

| 2 | 3.60, t (5.8) | 64.0 | CH | H-3, H-4, H-3′ |

| 3 | 2.12, m | 33.5 | CH2 | H-2, H-4 |

| 4 | 2.68, m | 32.2 | CH2 | H-2, H-6, H-10 |

| 5 | / | 142.1 | C | H-3, H-4, H-7, H-9 |

| 6, 10 | 7.23, m | 129.9 | CH | H-4, H-8 |

| 7, 9 | 7.30, m | 130.3 | CH | / |

| 8 | 7.19, m | 128.0 | CH | H-6, H-10 |

| 2′ | / | 174.1 | C | H-3′, H-7′ |

| 3′ | 4.05, d (10.3) | 61.5 | CH | H-2 |

| 4′ | 1.70, m; 2.10, m | 29.3 | CH2 | H-3′ |

| 5′ | 1.64, m; 1.97, m | 28.2 | CH2 | H-3′, H-7′ |

| 6′ | 1.28, m; 1.75, m | 28.5 | CH2 | H-4′ |

| 7′ | 3.16, m | 42.5 | CH2 |

Fig. 2.

Important 1H-1H COSY and HMBC correlations for target impurity

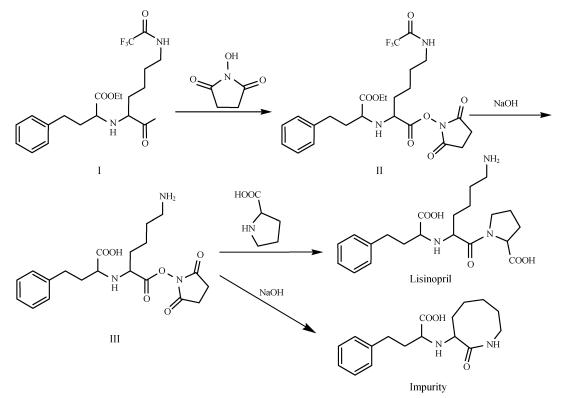

Formation of impurity

According to the synthesis route of lisinopril (Sun and Zhi, 1997), the formation of impurity could be explained by the reaction of intermediate II with NaOH to give intermediate III, which might be further cyclized to yield the impurity (Fig.3).

Fig. 3.

Proposed pathway for formation of impurity

CONCLUSION

Using multiple dimensional NMR technique, we successfully identified the structure of a novel trace-level impurity in bulk drug of lisinopril. The formation of the impurity was discussed. This work is of great importance for quality control of lisinopril and monitoring of the reactions during the development process of lisinopril.

Footnotes

Project (No. 20375036) supported partly by the National Natural Science Foundation of China

References

- 1.Cao XJ, Tai YP, Sun CR, Wang KW, Pan YJ. Characterization of impurities in semi-synthetic vinorelbine bitartrate by HPLC-MS with mass spectrometric shift technique. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2005;39(1-2):39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goa KL, Balfour JA, Zuanetti G. Lisinopril. A review of its pharmacology and clinical efficacy in the early management of acute myocardial infarction. Drugs. 1996;52(4):564–588. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199652040-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krishna Reddy KVSR, Mahender Rao S, Om Reddy G, Suresh T, Moses Babu J, Dubey PK, Vyas K. Isolation and characterization of process-related impurities in linezolid. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2002;30(3):635–642. doi: 10.1016/S0731-7085(02)00353-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lancaster SG, Todd PA. Lisinopril. A preliminary review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use in hypertension and congestive heart failure. Drugs. 1988;35(6):646–669. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198835060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simpson K, Jarvis B. Lisinopril: a review of its use in congestive heart failure. Drugs. 2000;59(5):1149–1167. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun AM, Zhi YH. Synthetic Method for Lisinopril. 1140708. CN Patent. 1997

- 7.Zhou H, Tai YP, Sun CR, Pan YJ. Separation and characterization of synthetic impurities of triclabendazole by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2005;37(1):97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2004.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]