Abstract

Compulsory vaccination has contributed to the enormous success of US immunization programs. Movements to introduce broad “philosophical/personal beliefs” exemptions administered without adequate public health oversight threaten this success. Health professionals and child welfare advocates must address these developments in order to maintain the effectiveness of the nation’s mandatory school vaccination programs.

We review recent events regarding mandatory immunization in Arkansas and discuss a proposed nonmedical exemption designed to allow constitutionally permissible, reasonable, health-oriented administrative control over exemptions. The proposal may be useful in political environments that preclude the use of only medical exemptions. Our observations may assist states whose current nonmedical exemption provisions are constitutionally suspect as well as states lacking legally appropriate administrative controls on existing, broad non-medical exemptions.

COMPULSORY VACCINATION has contributed to the success of US immunization programs in eradicating smallpox, eliminating polio, and reducing by 98–99% the incidence of most other vaccine-preventable diseases.1–3 The utility of US school vaccination requirements in preventing disease and introducing new vaccines has been well documented.4–9 With the success of immunization programs in effectively controlling vaccine-preventable diseases has come, paradoxically, a problem for future disease prevention: public attention has shifted from the risks of disease to the risks of vaccination.10 States’ policies for mandatory school immunization are increasingly major focal points for attack owing to increased public and media focus on vaccine safety and public perception of insufficient regulatory oversight.

School vaccination programs in the United States form a relatively fragile patchwork of differing state laws—under the US Constitution, most power to protect the public’s health and safety (“police powers”) is reserved for the states. Each state has therefore passed its own laws requiring vaccination before school entrance while permitting various kinds of exemptions.

States offer exemptions to mandatory immunization requirements that fall into 2 very broad categories: “medical” (where vaccination is medically contraindicated) and “nonmedical” (where exemptions are given for reasons of social policy). There is no constitutional requirement for states to offer nonmedical exemptions11 though most states do. Nonmedical exemptions currently used by the states can be characterized broadly as either “religious” (explicitly including religious belief as a criterion for exemption) or “philosophical/personal beliefs” (accepting any secular personal conviction as a criterion for exemption). As of July 2002, 48 states offered religious exemptions and 17 states permitted philosophical/personal beliefs exemptions. The focus of many groups opposed to compulsory vaccination over the last several years has been to expand states’ adoption of broad philosophical/personal beliefs exemptions incorporating minimal or no public health–oriented administrative oversight.

Yet unvaccinated children with nonmedical exemptions to immunization requirements are at greater risk of contracting vaccine-preventable diseases while also increasing the risk of disease transmission to others in the community who may have medical contraindications to vaccination (medical exemptions), who are too young to be vaccinated, or who have not developed a protective response to vaccination (vaccine failures).12,13 Safeguarding mandatory school vaccination programs should therefore be among the foremost concerns of health professionals and child welfare advocates.

A CHANGING LANDSCAPE FOR NONMEDICAL EXEMPTIONS

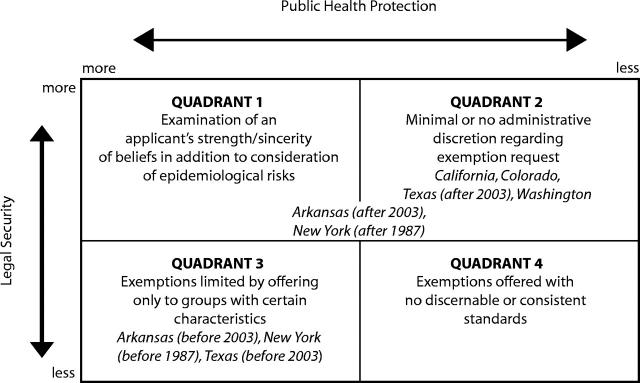

State vaccination policies for nonmedical exemptions must negotiate 2 objectives: (1) maintaining sufficiently high levels of immunization among children by reasonably restricting the number of exemptions granted while (2) ensuring that exemptions, when adopted, are fair. These relationships are depicted in the law/health exemption matrix shown in Figure 1 ▶, showing how legal and public health considerations interact in different kinds of nonmedical exemptions. Ideally the goal of health professionals, child welfare advocates, and legislators should be to locate their states’ nonmedical exemptions fully within quadrant 1 of the matrix. Exemptions that offer both less legal validity and less public health protection (quadrant 4 of the matrix) should be avoided.

FIGURE 1—

Potential nonmedical vaccination exemption scenarios (with state examples in italics) and level of public health protection/legal security.

Note. The degree of public health protection is based on administrative procedures that may limit the number and clustering of exemptions. The degree of legal security is based on the potential for constitutional invalidity.

State immunization programs offering only medical exemptions fall within quadrant 1 of the matrix shown in Figure 1 ▶. They are both legally acceptable and maximally protective of public health. However, during our recent experience in the state of Arkansas, we helped achieve a more reasonable goal of striking an acceptable balance between protecting public health and acknowledging parents’ interests in directing preventive health care for their children.

We hypothesized that, while allowing only medical exemptions would have minimized individual and community risks associated with lowered vaccination rates, a political backlash might ultimately have undermined the effectiveness of school vaccination requirements, as forcing vaccinations upon children of parents strongly opposed to immunization might add to anti-vaccination efforts. That hypothesis is clearly subject to a number of factors, including (1) public perceptions of the risks of disease and urgency of the health threat, (2) the characteristics and culture of the population of interest, (3) public trust of public health authorities and government, (4) public perceptions regarding the benefits and detriments of vaccination, and (5) the relative absence of diseases preventable by immunization. These considerations require further exploration.

Historically, some states have controlled the number of non-medical exemptions granted by limiting the kinds of people to whom exemptions can be given. States including Texas and Arkansas employed religious exemptions requiring parents to demonstrate membership in recognized religions opposed to vaccination (these kinds of exemptions are depicted in quadrant 3). But such provisions are vulnerable to constitutional challenges. States using restrictive religious exemptions run the risk of engaging in a constitutionally impermissible preference toward certain religions, whereas the First Amendment’s “clearest command . . . is that one religious denomination cannot be officially preferred over another.”14 The result of potential constitutional challenges has been that several states have been forced to modify their non-medical exemptions, and others have sought to avert legal action by rewriting their religious exemption provisions.

A concern for health professionals and child welfare advocates is whether these revisions, by relaxing the requirements for exemption, tend to produce exemption provisions that fall into quadrant 2 of the matrix. Such provisions could guarantee legal safety but, in our view, will jeopardize immunization coverage among children. Public health is endangered when states—in an effort to guarantee legal neutrality—adopt nonmedical exemptions, which diminish or minimize public health or educational authorities’ control over the numbers of exemptions given. For example, some states (e.g., California) allow parents to claim exemptions simply by signing preprinted forms. Consequently, it is easier to claim an exemption than to document a child’s vaccination status.10 Groups opposed to compulsory vaccination have also diluted the efficacy and legitimacy of existing administrative controls by disseminating preformatted statements and materials used presumably to ease the preparation and approval of vaccine exemption requests.15

States may delegate power to local government authorities, ultimately including school and health boards, to condition school attendance on local immunization requirements.16 But in some states (e.g., Colorado, Washington), most schools do not have or reject the authority to deny exemption requests and seldom impose any significant procedural requirements (such as annual exemption renewal). States that permit exemptions easily are associated with higher rates of exemptions17 and, within states, schools that permit exemptions easily are associated with higher exemption rates still.18

Legislation to relax immunization requirements or add broad philosophical/personal beliefs exemptions was introduced in at least 8 states during 1999.12 By 2003, legislatures in 13 states were considering bills related to mandatory school vaccination requirements;19 for 12 of these states, the proposed legislation would likely result in expanding the number of exemptions granted.20 As of April 2004, 8 states were considering new or broader exemption legislation for the 2004 session.20

The problem of inadequate public health oversight is not confined to philosophical/personal beliefs exemptions. As of 1998, 39% (n = 13) of the states that offered religious (but not philosophical/personal beliefs) exemptions lacked any authority to deny an exemption request.21 These factors presage a gradual erosion of “herd immunity” (resistance of a group to an attack by a disease to which a large proportion of the members of the group are immune)22 dependent upon high levels of immunization coverage.

NONMEDICAL EXEMPTIONS IN ARKANSAS: A CASE IN POINT

Arkansas, while historically not providing any exemptions from school vaccination requirements on nonmedical grounds,23,24 introduced a religious exemption in 1967.25 The Arkansas exemption was to be granted if “immunization conflicts with the religious tenets and practices of a recognized church or religious denomination of which the parent or guardian is an adherent or member.”26 Parents seeking exemptions on religious grounds were asked to complete forms for submission to the Arkansas Department of Health; they were also asked for written statements from a church establishing a conflict between vaccination and religious tenets and practices, certification of their membership, and copies of church documents.27 Arkansas Department of Health officials determined what constituted a “recognized church or religious denomination” by considering such factors as (1) the permanent address of the applicant’s church, (2) the size of the congregation, (3) the church’s meeting practices, (4) church organizational documents, (5) the written doctrine of the church, and (6) other legal documents supplied by the church.26

Plaintiffs in 2 cases decided by federal courts in Arkansas in 2002—Boone v Boozman17 and McCarthy v Boozman27—challenged the state’s religious exemption with separate arguments under the establishment and free exercise clauses of the First Amendment and the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The primary basis of their claims was that the religious exemption permitted discrimination against nondenominational, nonsectarian individuals with sincere religious beliefs. The provision, they argued, also allowed government officials to make choices not permissible by the Constitution regarding which religions they would “recognize” and which they would not. The federal courts agreed and struck down the Arkansan nonmedical exemption provision.

The effect of the rulings in the Arkansas cases was not to eliminate the mandatory school immunization requirement but to eliminate the constitutionally invalid nonmedical exemption provision. This result served as a rallying point for groups opposed to mandatory immunizations. Several legislative bills were filed that would have introduced a new, broader nonmedical exemption allowing parents to “opt out” of their children’s immunization requirements.

In response, health advocacy groups, clinical providers, and insurance companies opposed what they perceived to be a threat to immunization programs and public health. The Arkansas Department of Health, unable as a state agency to lead the discussion of what was characterized as a political question, requested stakeholders led by the Arkansas Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics to address the exemption issue. Faculty members at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Vaccine Safety and the Johns Hopkins Center for Law and the Public’s Health, in consultation with the Arkansas Medical Society, agreed to draft a proposal for a new exemption provision.

A Balanced Proposal for Nonmedical Exemption

The draft exemption (highlights shown in Table 1 ▶) proposed by the institute, the center, and the medical society was developed in accordance with 9 guiding principles (Table 2 ▶) and is available online.28 Central themes of the guiding principles are that (1) public health interests can be stronger than interests of individual and parental autonomy, (2) imposing mandatory health requirements in situations of low epidemiologic risk unnecessarily constrains individual interests and can undermine the effectiveness of public health activities, (3) participation in public health programs should be encouraged through both program design (the environment) and education (behavior), and (4) public health agencies should have ultimate authority to determine public health risk and, therefore, the number and timing of any nonmedical immunization exemptions.

TABLE 1—

Selected Components of Arkansas Draft Nonmedical Vaccination Exemption Provision

| Component | Explanation |

| Requirement of firmly held, bona fide belief | Constitutionally permitted inquiry into the strength and sincerity (not validity) of the parent’s beliefs |

| Proof of health department–approved vaccine counselinga | Ensures that the parent is adequately informed of the risks of not vaccinating and demonstrates the strength and sincerity of the belief held |

| Signed personal statement by the parent explaining (1) strength and duration of belief and (2) understanding of risks and benefits to child and public health | Forms the basis of the health department’s constitutionally permitted inquiry while minimizing use of readily available, predrafted pro forma documents in favor of a fully informed parental decision not to vaccinate |

| Department discretion to reject based on individual and community risks | Provides that ultimate authority to determine exemptions may be based on a health department assessment of community and individual risks of incurring vaccine-preventable disease |

| Annual renewala | Ensures reevaluation of decisions not to vaccinate and decisions to exempt based on latest medical developments and public health data |

| Ongoing central exemption trackinga | Allows monitoring of exemption rate trends and assists in profiling child, school, and community risk |

aProvisions included in the final Arkansas philosophical exemption.

TABLE 2—

Guiding Principles for Crafting a Draft Nonmedical Vaccination Exemption Provision

|

The draft exemption may be useful in political environments that preclude the use of only medical exemptions, as was the case in Arkansas. The draft exemption sought to avoid the legal and public health dangers presented by many states’ non-medical exemptions in at least 2 ways. First, it attempted to minimize pro forma nonmedical exemption procedures, which, in some states, can make claiming and receiving an exemption easier than immunizing a school-aged child. Although it is not permissible to prefer one applicant over another based upon the degree to which the respective religions are “recognized,” it is constitutionally permissible to evaluate nonmedical exemption requests based on the sincerity of a belief.29 Following litigation,30 the New York State legislature rewrote section 2164 of the New York Public Health Law to require that a parent maintain “genuine and sincere religious beliefs” instead of being a “bona fide member of a recognized religious organization.”31 The legal examinations of the strength of belief for conscientious objectors to military conscription can serve as a model for nonmedical vaccination exemptions.32

Second, the draft exemption sought to ensure that public health officials enjoy sufficient authority to adapt the nonmedical exemption system commensurate with epidemiologic risk. Health departments are best suited to determine epidemiologic risk, based on knowledge of current epidemiologic trends and circumstances. Within this context the draft exemption recognized that public health protection could, in some circumstances during periods of serious public health risk, supersede individuals’ interests in nonmedical exemptions. Any authority exercised by health officials naturally must be subject to regulatory and judicial oversight and justified by sound public health practice. The draft exemption also attempted to ensure that parents requesting nonmedical exemptions received individual educational counseling on the risks and benefits of vaccination.

A draft was circulated among vaccine stakeholders for informal review. Comments were considered, and a final draft was offered by the Arkansas Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics as a compromise between those advocating elimination of all nonmedical exemptions and those advocating a broad philosophical/personal beliefs exemption.

The Final Arkansas Provision

Ultimately the Arkansas General Assembly passed a statute incorporating a philosophical/personal beliefs exemption. The final exemption provision possesses many of the draft exemption’s characteristics, but also has some fundamental differences. For example, the Arkansas exemption now includes a provision for annual renewal, whereas the Arkansas Department of Health rejected ultimate authority to deny exemption requests. Consequently, Arkansan parents are granted exemptions if they (1) provide a notarized statement requesting an exemption, (2) complete an educational component on the risks and benefits of vaccination sponsored by the Department of Health, and (3) sign a statement of informed consent, including a “statement of refusal to vaccinate” and acknowledgment that their children may be removed from schools during an outbreak. The Arkansas law also includes a requirement not included in the draft exemption: the Department of Health must conduct surveillance and assess disease risks associated with exemptions. Additionally, the law requires formal reporting of the rates of exemptions and incidence of disease to the State Vaccine Medical Advisory Committee Board.

The final Arkansas exemption, like our draft exemption, should not be accepted uncritically as a model. We believe, for example, that retaining authority to deny exemption requests within states’ health departments is essential. The risks associated with granting nonmedical exemptions may be very low if the number of exemptions is small and exempted individuals are randomly distributed throughout the population; conversely, risk increases as the prevalence of exempted individuals increases and/or as exempted individuals cluster into geographic or social spheres.10,11

Effects on individual interests also vary unpredictably, as the perceived burden of vaccination is greater for parents with strongly held beliefs against vaccination compared with parents who are in favor of vaccination or whose beliefs are less strongly held. We believe that requiring counseling of patients by their individual health care providers, which the Arkansas exemption does not do, enhances opportunities for addressing patients’ specific needs and building trusting partnerships in health care relationships.

Effects on Immunization Coverage

It is impossible to determine at this stage whether the Arkansas exemption, as adopted, should be considered a success. A true comparison of the public health impact of the legislation that would have occurred without the input of the Arkansas consortium is not possible. However, in the absence of a concerted effort by the medical and public health community, it seems likely that Arkansas would have adopted an exemption scheme tending to fall within quadrant 2 of the law/health exemption matrix shown in Figure 1 ▶. The state of Texas, for example, has recently rewritten its nonmedical exemption provision. The Texas statute, which previously afforded a vaccination exemption only to members of recognized religions, now offers a very broad exemption that may be more widely used than the Arkansas exemption due to a lack of administrative control. Arkansas might have adopted nonmedical exemptions similar to those available in Colorado, California, and Washington. With minimal procedural and substantive requirements such an exemption provision would likely have been legal but also would have made exemptions very easy to obtain.

Preliminary data indicate a 67% increase in the rate of exemptions in the year after Arkansas adopted its philosophical/personal beliefs exemption as compared to the 2 prior years (from 419 to 701 exemptions). Further studies are under way to characterize and describe this impact over several years. Possible causes of the increase in exemptions include but are not limited to (1) publicity attending the recent court cases and adoption of the new exemption provision, (2) the design of the exemption, and (3) the administration of the exemption. The legislation may need to be reviewed if the number of exemptions continues to climb at this rate.

CONCLUSION

The Arkansas case study highlights the challenges of working on complex, emotionally charged issues at the juncture of politics and public health. Following the federal courts’ decisions and their ramifications, the Arkansas legislature became receptive to a very broadly written philosophical/personal beliefs exemption to the state’s mandatory school immunization program. Up to this point, groups opposed to immunization laws have not been highly successful in working to relax the requirements for non-medical exemptions or to add broad philosophical/personal beliefs exemptions where they do not already exist. Groups opposed to compulsory vaccination may use the Arkansas experience as a model to challenge mandatory school immunization programs nationally.

The draft exemption may be useful to other states struggling with the constitutionality of non-medical exemptions and efforts to balance individual interests against the tremendous individual and public health benefits of vaccination. The draft exemption, modified to take local conditions into account, may be useful for health professionals and public health advocates dealing with the complex legal and political environment of school immunization requirements. States should proactively review nonmedical exemptions to increase the likelihood of proper time and consideration being given to this important issue.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the stakeholders who provided informal review of the draft exemption.

Human Participant Protection No institutional review board approval was required for this study.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors D. A. Salmon, J. W. Sapsin, S. Teret, and N. A. Halsey developed the draft exemption provision in consult with R.F. Jacobs. R.F. Jacobs, J.W. Thompson, and K. Ryan worked with state partners (State Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Infectious Diseases section of Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Arkansas Advocates for Families and Children, and the Arkansas Department of Health) in introducing and revising the Arkansas exemption. All authors contributed to the writing of the article.

References

- 1.Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999; 48(12):241–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Impact of vaccines universally recommended for children—United States, 1990–1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(12):243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orenstein WA, Hinman AR. The immunization system in the United States—the role of school immunization laws. Vaccine. 1999;17(suppl 3): S19–S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orenstein WA, Hinman AR, Williams WW. The impact of legislation on immunisation in the United States. In: Hall R, Richters J, eds. Immunisation: The Old and the New. Canberra: Public Health Association of Australia; 1992: 58–62.

- 5.Middaugh JP, Zyla LD. Enforcement of school immunization law in Alaska. JAMA. 1978;239:2128–2130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Measles—Florida, 1981. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1981;30(48): 593–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowinkle EW, Barid S, Bass CM. A compulsory school immunization program in Tennessee. Public Health Rep. 1981;96(1):61–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.School immunization requirements for measles—United States, 1981. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1981;30(13): 158–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orenstein WA, Halsey NA, Hayden GF, et al. From the Center for Disease Control: current status of measles in the United States, 1973–1977. J Infect Dis. 1978;137:847–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen RT, Hibbs B. Vaccine safety: current and future challenges. Pediatr Ann. 1998;27:445–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prince v Massachusetts, 321 US 158 (1944).

- 12.Salmon DA, Haber M, Gangarosa EJ, Phillips L, Smith N, Chen RT. Health consequences of religious and philosophical exemptions from immunization laws: individual and societal risks of measles [erratum appears in JAMA. 2000;283:2241]. JAMA. 1999;282: 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feikin DR, Lezotte DC, Hamman RF, Salmon DA, Chen RT, Hoffman RE. Individual and community risks of measles and pertussis associated with personal exemptions to immunizations. JAMA. 2000;284:3145–3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larson v Valente, 456 US 228, 244,246 (1982).

- 15.Farina v Bd of Educ of the City of New York, 116 F Supp 2d 503 (SD NY 2000).

- 16.Zucht v King, 260 US 174 (1922).

- 17.Boone v Boozman, 217 F Supp 2d 938 (ED Ark 2002).

- 18.Salmon DA, Omer SB, Moulton LH, et al. The role of school policies and implementation procedures in school immunization requirements and nonmedical exemptions. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:436–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Conference of State Legislatures. Immunization legislation 2003. Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/programs/health/Immleg2003.htm. Accessed January 22, 2005.

- 20.National Conference of State Legislatures. Immunization legislation 2004. Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/programs/health/imleg04.htm. Accessed January 22, 2005.

- 21.Rota JS, Salmon DA, Rodewald LE, Chen RT, Hibbs BF, Gangarosa EJ. Processes for obtaining nonmedical exemptions to state immunization laws. Am J Public Health. 2000;91:645–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordis L. Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 2000:20.

- 23.Cude v State, 377 SW2d 816 (Ark 1964).

- 24.Wright v DeWitt School District, 385 SW2d 644 (Ark 1965).

- 25.1983 Ark Acts 150.

- 26.Ark Code Ann §6-18–702(d)(2).

- 27.McCarthy v Boozman, 212 F Supp 2d 945 (WD Ark 2002).

- 28.Salmon DA, Sapsin JW, Teret S, et al. Draft exemption proposed by The Institute for Vaccine Safety, The Johns Hopkins Center for Law and the Public’s Health, and The Arkansas Medical Society. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Institute for Vaccine Safety; 2005. Available at: http://www.vaccinesafety.edu/DraftExemption.htm. Accessed January 22, 2005.

- 29.US v Seeger, 380 US 163,185 (1965).

- 30.Sherr v Northport-East Northport Union Free School District, 672 F Supp 81 (ED NY 1987).

- 31.Turner v Liverpool Central School District, 186 F Supp 2d 187 (ND NY 2002).

- 32.Salmon DA, Siegel AW. Religious and philosophical exemptions from vaccination requirements and lessons learned from conscientious objectors from conscription. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:289–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]