Abstract

Here we have examined the function of Pom34p, a novel membrane protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, localized to nuclear pore complexes (NPCs). Membrane topology analysis revealed that Pom34p is a double-pass transmembrane protein with both the amino (N) and carboxy (C) termini positioned on the cytosolic/pore face. The network of genetic interactions between POM34 and genes encoding other nucleoporins was established and showed specific links between Pom34p function and Nup170p, Nup188p, Nup59p, Gle2p, Nup159p, and Nup82p. The transmembrane domains of Pom34p in addition to either the N- or C-terminal region were necessary for its function in different double mutants. We further characterized the pom34ΔN nup188Δ mutant and found it to be perturbed in both NPC structure and function. Mislocalization of a subset of nucleoporins harboring phenylalanine–glycine repeats was observed, and nuclear import capacity for the Kap104p and Kap121p pathways was inhibited. In contrast, the pom34Δ pom152Δ double mutant was viable at all temperatures and showed no such defects. Interestingly, POM152 overexpression suppressed the synthetic lethality of pom34Δ nup170Δ and pom34Δ nup59Δ mutants. We speculate that multiple integral membrane proteins, either within the nuclear pore domain or in the nuclear envelope, execute coordinated roles in NPC structure and function.

IN eukaryotic cells, translocation of macromolecules across organellar membranes requires specialized protein complexes embedded at the sites of entry and/or exit (Schnell and Hebert 2003). Nucleocytoplasmic transport is mediated through nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) anchored in a nuclear envelope (NE) pore. These NPCs are formed from the assembly of at least 30 nucleoporins (Nups), in multiple copies each, that are organized in biochemically discrete subcomplexes and localized to specific NPC substructures (Fahrenkrog and Aebi 2003; Suntharalingam and Wente 2003). In sum, NPCs have a predicted mass of ∼44 MDa in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and 60 MDa in vertebrates (Rout et al. 2000; Cronshaw et al. 2002). Three-dimensional morphology studies have observed close contact between the proteinaceous NPC structure and surrounding NE (pore membrane), supporting models wherein nuclear pore membrane proteins (Poms) play key roles in organizing NPC architecture (Allen et al. 2000; Stoffler et al. 2003; Beck et al. 2004). Moreover, the interactions between integral membrane proteins in the lumen are speculated to promote fusion of the inner and outer nuclear membranes for formation of the nuclear pore in the intact NE (Goldberg et al. 1997). The mechanisms by which the membrane fusion and subsequent recruitment of distinct NPC subcomplexes occur have not been fully elucidated.

Two vertebrate Poms have been identified and characterized: gp210 and Pom121. Both are type I transmembrane proteins with single membrane-spanning segments and their amino (N)-terminal regions positioned in the NE lumen (Wozniak et al. 1989; Greber et al. 1990; Hallberg et al. 1993; Soderqvist and Hallberg 1994). However, they share no sequence homology and likely play distinct roles in NPC structure and function. Most of the gp210 mass is lumenally localized. In contrast, the majority of Pom121 is exposed to the cytosolic/pore side of the membrane. After integration into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), gp210 and Pom121 are sorted to the nuclear pore membrane by lateral diffusion through the functionally continuous ER (Yang et al. 1997; Imreh et al. 2003). During postmitotic NE reformation in mammalian cells, Pom121 is recruited to the nuclear periphery at a very early stage, while the recruitment of gp210 occurs relatively late (Bodoor et al. 1999). Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching experiments of interphase NPCs has shown that gp210 is notably dynamic with a relatively rapid exchange rate at NPCs. In contrast, Pom121 is markedly stable with a much slower exchange rate (Eriksson et al. 2004; Rabut et al. 2004). Finally, in a recent study of mitotic in vitro NPC/NE assembly (Antonin et al. 2005), inhibition of Pom121 function or depletion of Pom121-containing vesicles blocks membrane vesicle fusion around chromatin. Depletion of gp210 vesicles does not perturb assembly. However, it is unknown whether Pom121 is sufficient for pore formation and whether this is linked to gp210 roles in NPC structure and function. Taken together, Pom121 likely plays a central role in regulating NE/NPC biogenesis and anchorage of the NPC in the NE.

Whereas the majority of the peripheral Nups are structurally or functionally conserved across species (reviewed in Suntharalingam and Wente 2003), gp210 and Pom121 do not possess any significant sequence similarity with proteins predicted from the open reading frames annotated in the S. cerevisiae genome. Instead, three distinct Poms have been identified in budding yeast: Ndc1p, Pom152p, and Pom34p (Wozniak et al. 1994; Chial et al. 1998; Rout et al. 2000). Ndc1p is the only Pom encoded by an essential gene, harbors six or seven potential membrane-spanning regions, and is localized to both NPCs and spindle pole bodies (Chial et al. 1998). Unlike Ndc1p, both Pom152p and Pom34p reside exclusively within the NPC (Wozniak et al. 1994; Rout et al. 2000). Pom152p is a type II integral membrane protein with a single transmembrane segment and the majority of the protein positioned in the NE lumen (Tcheperegine et al. 1999). Several studies have revealed roles for Ndc1p and Pom152p in NPC molecular organization. A conditional ndc1-39 allele has genetic interactions with another NPC assembly mutant nic96-1, and at the restrictive temperature ndc1-39 cells have defects in incorporating Nup49p into the NPC (Lau et al. 2004). Although POM152 is dispensable for cell growth, the pom152 null (Δ) mutant results in lethality when combined with mutants allelic to NUP170, NUP188, NUP59, or NIC96 (Aitchison et al. 1995; Nehrbass et al. 1996). The pom152Δ nup170Δ double mutant has massive NE extensions and invaginations and long stretches of NE without detectable NPCs.

Pom34p was discovered in a comprehensive proteomics study of enriched S. cerevisiae NPCs, and localization and biochemistry results have indicated that Pom34p is a novel NPC constituent (Rout et al. 2000). However, its function in NPC structure and function remains uncharacterized. In this report, we have conducted a series of experiments to define the membrane topology of Pom34p. Using genetic approaches, we have demonstrated that Pom34p has broad functional interactions with other Nups. In particular, the relationship between POM34 and POM152 has been investigated. By dissecting the functional domains of Pom34p and examining the influence on NPC structure in the context of nup mutants, we provide evidence that Pom34p is involved in the molecular organization of NPC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains:

The S. cerevisiae strains were grown in either rich (YPD: 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) or synthetic minimal (SM) media lacking appropriate amino acids and supplemented with 2% glucose. 5-Fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA; United States Biological) was used at a concentration of 1.0 mg/ml. Kanamycin resistance (KANR) was selected on medium containing 200 μg/ml G418 (United States Biological). Yeast transformations were performed using the lithium acetate method (Ito et al. 1983), and general yeast manipulations were conducted as described elsewhere (Sherman et al. 1986).

All yeast strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. Unless indicated otherwise, the null (Δ) mutants used in these studies were obtained from Research Genetics (Birmingham, AL). The pom34Δ∷spHIS5 strain was made according to the method of Baudin et al. (1993) with pGFP-HIS5 (gift from J. Aitchison) as template and two 80-mer oligonucleotides (1314, GTG CTA ATA GTA ATA ATG ATA GAA ATA ATA ACA ATT AAT AAG ATG GTT ATG ATG AAC GGT GAA GCT CAA AAA CTT ATT; 1316, ATA CTT ATT TCC AAA CTA TTG GTA ATG GTT GCC GCT AAT CAT ATG TAA AAT ATA AAT AGG AGC TGA CGG TAT CGA TAA GCT T). PCR amplification generated a GFP-spHIS5 fragment flanked on one end by ∼60 bp of sequence with homology 138–82 bp upstream of the POM34 coding region and on the other end by ∼60 bp of sequence with homology 50–110 bp downstream. The resulting fragment contained the full-length Schizosaccharomyces pombe HIS5 (homologous to S. cerevisiae HIS3) and a GFP sequence that lacked a promoter. The fragment was transformed and integrated into diploid SWY595 cells. The resulting heterozygous diploid was sporulated, and tetrads were dissected to obtain viable haploid null strains (SWY2565 and SWY2566). PCR was used to confirm the integration.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| PMY17 | MATapom152-2∷HIS3 ade2-1 ura3-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 can1-100 | Wozniak et al. (1994) |

| psl21 | MATα pom152-2∷HIS3 nup170-21 ade2 ade3 ura3 his3 trp1 leu2 can1 + pCH1122-POM152 (ADE3-URA3) | Aitchison et al. (1995) |

| SWY518 | MATaade2-1∷ADE2 ura3-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 can1-100 | Bucci and Wente (1997) |

| SWY595 | MATa/MATα ade2-1∷ADE2/ade2-1∷ADE2 ura3-1/ ura3-1 his3-11,15/his3-11,15 trp1-1/trp1-1 leu2-3,112/leu2-3,112 can1-100/can1-100 | Bucci and Wente (1997) |

| SWY2565 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 ade2-1∷ADE2 ura3-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 can1-100 | This study |

| SWY2566 | MATapom34∷spHIS5 ade2-1∷ADE2 ura3-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 can1-100 | This study |

| SWY3093 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 pom152∷HIS3 ura3-1 his3-11,15 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 can1-100 ade2-1 | This study |

| SWY3125 | MATapom34∷spHIS5 nup188∷KANR his3 ura3 trp1 leu2 lys2 + pSW1516 | This study |

| SWY3132 | MATapom34∷spHIS5 nup170∷KANR his3 ura3 trp1 leu2 met15 + pSW1516 | This study |

| SWY3139 | MATapom34∷spHIS5 nup59∷KANR his3 ura3 leu2 met15 + pSW1516 | This study |

| SWY3142 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 nup53∷KANR his3 ura3 trp1 leu2 met15 | This study |

| SWY3149 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 nup157∷URA3 his3 ura3 trp1 leu2 lys2 | This study |

| SWY3153 | MATapom34∷HIS5 nic96∷HIS3 ade2 his3 ura3 trp1 leu2 lys2 + pUN100-LEU2-nic96-1[P332L, L260P] | This study |

| SWY3219 | MATα pom152∷HIS3 nup188∷KANR his3 ade2 lys2 ura3 leu2 + pCH1122-POM152(ADE3-URA3) | This study |

| SWY3305 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 gle2∷HIS3 ade2 his3 trp1 leu2 ura3 + pSW1516 | This study |

| SWY3309 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 gle1-2 his3 ura3 leu2 trp1 | This study |

| SWY3313 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 nup159-1(rat7-1) his3 ura3 leu2 + pSW1516 | This study |

| SWY3326 | MATapom34∷spHIS5 nup82-3(nle4-1) ade2 his3 ura3 trp1 leu2 + pSW1516 | This study |

| SWY3328 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 nup120∷HIS3 his3 ura3 leu2 | This study |

| SWY3334 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 nup42∷HIS3 his3 ura3 leu2 | This study |

| SWY3336 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 seh1∷HIS3 his3 ura3 trp1 leu2 | This study |

| SWY3337 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 nup2∷KANR his3 ura3 leu2 | This study |

| SWY3341 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 nup145ΔN∷LEU his3-11,15 ura3-1 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 can1-100 | This study |

| SWY3348 | MATapom34∷spHIS5 nup60∷KANR his3 ura3 leu2 | This study |

| SWY3352 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 nup100-1∷URA3 ade2-1 his3-11,15 ura3-1 trp1-1 leu2-3,112 can1-100 | This study |

| SWY3380 | MATapom34∷spHIS5 nup57-E17 his3-11,15 ura3-1 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 | This study |

| SWY3382 | MATapom34∷spHIS5 nup1-2∷LEU2 ade2 his3 ura3 leu2 trp1 lys2 | This study |

| SWY3384 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 nup116-5∷HIS3 ade2-1 his3-11,15 ura3-1 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 | This study |

| SWY3387 | MATα pom34∷spHIS5 nup133∷HIS3 ade2 his3 ura3 leu2 trp1 lys2 | This study |

| SWY3488 | MATα pom152∷HIS3 nup59∷KANR his3 ade2 lys2 ura3 leu2 + pCH1122-POM152(ADE3-URA3) | This study |

| SWY3489 | MATapom34∷spHIS5 nup188∷KANR his3 ura3 trp1 leu2 lys2 + pSW3044 | This study |

| SWY3490 | MATapom34∷spHIS5 nup188∷KANR his3 ura3 trp1 leu2 lys2 + pSW3042 | This study |

| SWY3581 | MATapom34∷spHIS5 nup145∷LEU2 his3-11,15 ura 3-1 leu2-3,112 can1-100 + pnup145-L2/URA3/CEN | This study |

References for the parental strains used in the double-mutant strain construction include: Wente et al. (1992), Belanger et al. (1994, 2004), Wente and Blobel (1994), Aitchison et al. (1995), Gorsch et al. (1995), Goldstein et al. (1996), Murphy and Wente (1996), Zabel et al. (1996), Emtage et al. (1997), Saavedra et al. (1997), Bailer et al. (1998), Bucci and Wente (1998), and the Research Genetics collection.

Plasmids and cloning:

Cloning of wild-type POM34:

The plasmids used in this work are described in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pRS316 backbone | Sikorski and Hieter (1989) | |

| pSW1516 | Full-length POM34 | This study |

| pRS315 backbone | Sikorski and Hieter (1989) | |

| pSW939 | Full-length SNL1 with SUC2 located at NsiI site | Ho et al. (1998) |

| pSW1517 | Full-length POM34 | This study |

| pSW3186 | Fragment containing endogenous POM34 promoter and the codons for the first three amino acid residues | This study |

| pSW3188 | Full-length POM34 with SpeI and XbaI sites inserted between amino acids 3 and 4, and SacII/SacI site inserted before stop codon | This study |

| pSW3189 | Full-length POM34 with myc-SUC2 inserted at SpeI site of pSW3193 | This study |

| pSW3190 | Full-length POM34 with myc-SUC2-myc inserted at SacI site of pSW3188 | This study |

| pSW3191 | Full-length POM152 at PstI site | This study |

| pSW3192 | Fragment of POM152 with the codons for residues from 1026 to 1337 replaced by myc-SUC2-myc | This study |

| pSW3193 | Full-length POM34 with c-myc inserted between codons for residues 3 and 4 | This study |

| pSW3194 | Full-length POM34 with four mutated amino acids between TM1 and TM2 for myc-Pom34p-(NXS/T)4, derived from pSW3193 | This study |

| pSW3195 | Full-length POM34 with protein A inserted at SacII/SacI site of pSW3188 | This study |

| pSW3196 | Fragment of pom34 with coding region for amino acids 62–85 replaced by codons for proline and glycine, for TM1Δ, derived from pSW3195 | This study |

| pSW3197 | Fragment of pom34 with coding region for amino acids 129–153 replaced by codons for proline and glycine, for TM2Δ, derived from pSW3195 | This study |

| pRS425 backbone | Christianson et al. (1992) | |

| pSW863 | Full-length POM152 in PstI site | This study |

| pSW3036 | Fragment encoding amino acids 1–160 of Pom34p | This study |

| pSW3042 | Fragment encoding amino acids 1–3, 55–299 of Pom34p | This study |

| pSW3044 | Full-length POM34 | This study |

| pSW3187 | Fragment containing endogenous POM34 promoter and the codons for the first three amino acids | This study |

| pSW3198 | Fragment encoding amino acids 1–3, 55–160 of Pom34p | This study |

| pSW3199 | Fragment of pom34 with coding region for amino acids 62–153 replaced by codons for proline and glycine | This study |

All the POM34 constructs are downstream of the endogenous promoter (360 bp). Additional vectors used include pFA6a-CTAP-MX6 (Tasto et al. 2001), pGAD-GFP (Shulga et al. 1996), pKW430 (Stade et al. 1997), pEB0836 (Romano and Michaelis 2001), and pNS167 (Shulga et al. 2000).

Epitope-tagged POM34 and site-directed mutagenesis:

Using pSW1516 as a template with forward primer 1668 (introducing SpeI and sequence encoding the myc epitope before the sequence for the fourth amino acid of Pom34p) and reverse primer 1653, PCR was used to generate a fragment that was digested with SpeI/SacI and ligated with the promoter sequence of pSW3186, resulting in pSW3193 (myc-POM34). Using pSW3193 as a template, site-directed mutagenesis was completed by PCR with oligonucleotide 1695, 5′-ATATA TCT AGA CGT CCG GTT GCA AAA CTG TCT CCC AAC-3′ (annealing to +268 to +300 bp of POM34, with XbaI and codon changes underlined), and with oligonucleotide 1697, 5′-AATTA TCT AGA ATC CAT CTG TAC AAC TTG ACA AAC CAC ACG TTA AAG AAG GCT AAC ATC TCC TAT CAC ACC ACG TTC AGT TGG TTG -3′ (annealing to +295 to +375 bp of POM34, with XbaI and point mutations underlined). The resulting PCR fragment was XbaI digested and ligated to yield pSW3194 [myc-pom34-(NXS/T)4]. The myc-pom34-(NXS/T)4 has four mutations that result in a protein with substitutions of L98T, M105N, F108N, and I117S between two potential membrane-spanning regions.

Construction of SUC2-fused genes:

A fragment encoding a c-myc fusion to Suc2p (myc-SUC2) was obtained using PCR and the template pSW939 with the following oligonucleotide pairs: forward primer 1681 (introducing SpeI and sequence for the myc epitope before the sequence for SUC2) and reverse primer 1703 (introducing SpeI after the SUC2 sequence) or forward primer 1679 (introducing SacI and the sequence encoding for the myc epitope before the SUC2 sequence) and reverse primer 1682 (introducing SacI and the sequence encoding for the myc epitope after the SUC2 sequence). The resulting myc-SUC2 or myc-SUC2-myc sequences were digested with either SpeI or SacI and inserted in frame into pSW3193 or pSW3188, respectively, generating plasmids with the gene fusions myc-SUC2-myc-POM34 (encoding Suc2pmyc-Pom34p) (pSW3189) or POM34-myc-SUC2-myc (encoding Pom34p-Suc2pmyc) (pSW3190). A 5.26-kb fragment encoding the full-length POM152 plus its flanking 800-bp promoter and 440-bp terminator regions was cloned into the PstI sites of pRS315 and pRS425 to obtain pSW3191 and pSW863, respectively. The coding sequence of POM152 (pSW3191) for amino acids 1026–1337 was removed by SacI digestion and replaced in frame by the above PCR product myc-SUC2-myc (from primers 1682 and 1679 with the pSW939 template). The resulting pSW3192 encoded a Pom152p-myc-Suc2p-myc (Pom152p-Suc2pmyc) fusion protein.

Deletion of transmembrane segment 1 or transmembrane segment 2:

The sequence-encoding protein A (containing four tandem repeats of IgG-binding domain) was obtained by PCR using the template pFA6a-CTAP-MX6 (Tasto et al. 2001). The SacII/SacI-digested PCR product was cloned in frame into pSW3188 to yield pSW3195, which encodes Pom34p-PrA. Using pSW3195 as a template, a pom34 DNA fragment lacking the coding region for potential transmembrane segment (TM)1 was amplified by PCR, using the primers 1688, 5′-AATTA CCC GGG AAC AAC ACT CAT GTT GGG AGA C-3′ and 1691, 5′-ATATA CCC GGG CGT CTC CAT TTC CTT GTT TAC-3′ (exogenous SmaI sites underlined). Similarly, the TM2 deletion fragment was amplified with the primers 1690, 5′-AATTA CCC GGG AAA GTA AGT GAT TTG AAT CTC-3′ and 1689, 5′-ATATA CCC GGG TTC TGC ATT CAA CCA ACT GAA C-3′(with exogenous SmaI sites underlined). The SmaI-digested PCR products were ligated to generate pSW3196 (TM1Δ-PrA) and pSW3197 (TM2Δ-PrA), respectively. The resulting deletion proteins had TM1 (residues 62–85) or TM2 (residues 129–153) replaced by proline and glycine derived from an exogenous SmaI restriction site.

Other POM34 constructs:

The following oligonucleotides were used to generate the POM34 deletion/truncation variants: 1657, 5′-ATATA GAG CTC TTA GAG ATT CAA ATC ACT TAC TTT-3′ (exogenous SacI site underlined); 1652, 5′-AATTA ACT AGT GTA AAC AAG GAA ATG GAG ACG-3′(exogenous SpeI site underlined); 1691; 1690; and the vector-based T3 and T7. Using template pSW1516 and combinations of these primers, DNA fragments of various truncation forms of POM34 were obtained by PCR and cloned into pRS425 or pSW3187 to generate pSW3036, pSW3042, pSW3198, and pSW3199. pom34-ΔC (sequence for residues 161–299 deleted), pom34-ΔN (residues 4–54 deleted), pom34-ΔNΔC (residues 4–54 and 161–299 deleted), and pom34-ΔTM (residues 62–153 deleted) were obtained, respectively.

Protein manipulation:

Biochemical fractionation:

Fifty milliliters of cells grown to midlog phase (OD600 = 0.4–0.5) in SM-leu/2% glucose were harvested by centrifugation. All of the following steps were in the presence of 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis). Cell pellets were pretreated (100 mm Tris, pH 9.4 and 10 mm DTT) for 10 min at room temperature, washed in spheroplast wash buffer [SWB: 1.2 m sorbitol, 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, and 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)], and then resuspended in 1 ml SWB with 0.1 mg/ml zymolyase 20T and 0.1 ml glusulase for 1.5 hr at 30°. After spheroplasting, cells were washed twice with 1.2 m sorbitol, 20 mm PIPES, pH 6.5, 1 mm MgCl2, and 0.5 mm PMSF; resuspended in 1 ml lysis buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 5 mm MgCl2, and 0.5 mm PMSF); and incubated on ice for 20 min with occasional vortexing. The resulting total (T) lysate was centrifuged at 17,900 × g at 4° for 45 min to yield a low-speed supernatant (S1) and postnuclear pellet (P1) fractions. For alkaline extraction, the P1 fraction was resuspended in extraction buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm PMSF, and 0.1 m Na2CO3, pH 11), incubated on ice for 20 min, and pelleted at 17,900 × g at 4° for 45 min. The resulting supernatant (S2) was combined with the prior S1, yielding the total S fraction. Equivalent amounts of the T lysate and S1 or S were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) for analysis with corresponding equivalents of the P1 or P2 fractions. All fractions were separated by electrophoresis in SDS polyacrylamide gels for immunoblot analysis. Immunoblotting was conducted with the following antibodies: rabbit anti-Snl1p (1:100, Ho et al. 1998), rabbit anti-Nup145C (1:100, Emtage et al. 1997), mouse monoclonal anti-myc (9E10, 1:500; Covance), rabbit anti-mouse (IgG, 1:1000; ICN Pharmaceuticals), rabbit anti-Nup116 glycine–leucine–phenylalanine–glycine (GLFG) (1:2500, Bucci and Wente 1998), rabbit anti-Nsp1p (1:2500, Nehrbass et al. 1990), mouse monoclonal anti-Pgk1p (mAb22C5, 1:1000; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and mouse monoclonal anti-Nop1p (mAb D77, 1:25; Aris and Blobel 1988).

Endoglycosidase H treatment:

Fifty milliliters of yeast cells were harvested at midlog phase. Whole-cell lysates were prepared by glass bead lysis in 350 μl lysis buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 6.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 2% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl) supplemented with 1× protease inhibitor mixture and 0.5 mm PMSF. The cells were vortexed vigorously for 12 min (1 min on, 2 min rest on ice) and then centrifuged at ∼200 × g for 10 min. Fifty microliters of the resulting supernatant were added to 150 μl 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.6), 0.5 mm PMSF, and digested with 15 milliunits endoglycosidase H (Endo H) (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) at 37° for 4 hr. For mock samples, the Endo H was eliminated. Samples were precipitated with TCA and separated by electrophoresis in SDS polyacrylamide gels for analysis by immunoblotting.

Fluorescence microscopy:

Indirect immunofluorescence experiments were performed as described previously (Wente et al. 1992), following a 10-min fixation in 3.7% formaldehyde and 10% methanol. The fixed cells were incubated for 16 hr at 4° with mAb414 (1:2 tissue culture supernatant, Davis and Blobel 1986), mouse monoclonal mAb118C3 against Pom152p (1:2 tissue culture supernatant, Strambio-de-Castillia et al. 1995), or affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal against the Nup116GLFG region (1:800, Bucci and Wente 1998). Bound antibody was detected by incubation with Alexa 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:400 dilution) or Alexa 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:300) for 60 min at room temperature. The cells were stained with 0.05 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) before visualizing under the fluorescence microscope (model BX50; Olympus, Lake Success, NY) using an Uplan 100×/1.3 objective. Images were captured using a digital camera (Photometrics Cool Snap HQ; Roper Scientific) with MetaVue software (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA). Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop 7.0.

3,3′-Dihexyloxacarbocyanineiodide staining:

3,3′-Dihexyloxacarbocyanineiodide (DiOC6) staining was performed as described elsewhere (Koning et al. 1993). Yeast cells in midlog phase growth were stained for 5 min with 1 μg/ml DiOC6 (Molecular Probes), using a 0.1 mg/ml ethanol stock. Stained cells were viewed by direct fluorescence microscopy as described above.

RESULTS

Pom34p is a double-pass transmembrane protein with both the N and the C terminus located on the cytosolic/pore side:

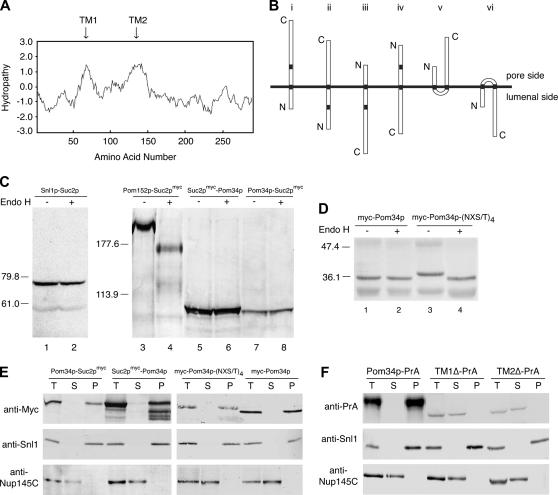

Hydropathy analysis of the Pom34p amino acid sequence identified two hydrophobic regions that could potentially serve as transmembrane segments (Figure 1A). In the 299-residue sequence, these extended from amino acid residues 64 to 84 (TM1) and 132 to 153 (TM2), respectively. Depending on whether one or both of these transmembrane domains are bona fide, there are six possible topology models for Pom34p relative to nuclear pore membranes (Figure 1B). To define the Pom34p membrane topology, we used a combination of approaches that have been established in previous studies of yeast ER membrane proteins. The fusion of Suc2p to protein regions is a common strategy for detecting localization in the ER/NE lumen (Sengstag 2000; Kim et al. 2003). The Suc2p fusion allows extensive N-linked glycosylation when lumenally localized, with a coincident Endo H-sensitive increase in molecular mass. Cytoplasmic Suc2p localization yields a nonglycosylated protein. To analyze Pom34p topology, we fused Suc2p, flanked by c-myc epitope tags, to either the N or the C terminus of wild-type Pom34p (Suc2pmyc-Pom34p and Pom34p-Suc2pmyc, respectively). As controls, we confirmed that the fusion proteins were functional by testing for their complementation of pom34Δ double mutants (see below).

Figure 1.

Pom34p is a double-pass integral membrane protein with the N- and the C-terminal regions exposed to the cytosol/pore. (A) Kyte–Doolittle hydropathy analysis (with a 20-amino-acid window size) (Kyte and Doolittle 1982) of Pom34p revealed two spans (arrows) extending from amino acid residues 64 to 84 (TM1) and 132 to 153 (TM2) with significant hydropathic character and length to be transmembrane segments. (B) Six possible topological models for Pom34p relative to the pore membrane are shown. N, amino; C, carboxy. (C) Cell extracts from strains expressing Snl1p-Suc2p (pSW939) (lanes 1 and 2), Pom152p-Suc2pmyc (pSW3192) (lanes 3 and 4), Suc2pmyc-Pom34p (pSW3189) (lanes 5 and 6), or Pom34p-Suc2pmyc (pSW3190) (lanes 7 and 8) were either mock digested (−) or treated with Endo H (+) and analyzed by immunoblotting using rabbit anti-Snl1p (lanes 1 and 2) or mouse monoclonal 9E10 (anti-c-Myc) (lanes 3–8). Molecular mass markers are indicated in kilodaltons. (D) Four potential N-linked glycosylation sites were generated between TM1 and TM2 of Pom34p by site-directed mutagenesis. Cell extracts from SWY2565 expressing either wild-type myc-Pom34p (lanes 1 and 2) or glycosylation site myc-Pom34p-(NXT/S)4 (lanes 3 and 4) were treated with Endo H as in C. Immunoblotting was conducted with the mouse monoclonal 9E10 (anti-c-Myc) antibody. (E) Spheroplast lysates from the pom34Δ strain expressing Suc2pmyc-Pom34p (pSW3189), Pom34p-Suc2pmyc (pSW3190), wild-type myc-Pom34p (pSW3193), or myc-Pom34p-(NXT/S)4 (pSW3194) were alkali extracted and separated into supernatant (S indicates S1 and S2) and pellet (P indicates P2) fractions by centrifugation. Fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting with the mouse monoclonal 9E10 (anti-Myc), rabbit anti-Snl1p or with rabbit anti-Nup145C antibodies. (F) Spheroplast lysates from pom34Δ cells expressing Pom34p-PrA, TM1Δ-PrA (lacking the TM1), or TM2Δ-PrA (lacking the TM2) were alkali extracted and separated into S and P fractions by centrifugation as in E. Fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting with rabbit anti-mouse (anti-protein A), rabbit anti-Snl1p, or rabbit anti-Nup145C antibodies.

To determine whether the N and/or C terminus of Pom34p is located on the lumenal side of the ER/NE membrane, the glycosylation status of Pom34p fusions was assessed. Cell lysates were prepared from a pom34Δ strain that harbored plasmids encoding either Suc2pmyc-Pom34p or Pom34p-Suc2pmyc, treated with Endo H, and analyzed by immunoblotting. As controls, the glycosylation states of a Pom152p-Suc2pmyc fusion in pom152Δ cells and a Snl1p-Suc2p fusion in snl1Δ cells were monitored. Pom152p and Snl1p have opposite topologies with the C terminus sequestered in the ER/NE lumen and cytosol, respectively (Ho et al. 1998; Tcheperegine et al. 1999). The Pom152p-Suc2pmyc fusion was sensitive to Endo H digestion as reflected by the migration shift (Figure 1C, lanes 3 and 4). On the other hand, the apparent molecular mass of Snl1p–Suc2p was not affected by Endo H treatment (Figure 1C, lanes 1 and 2). In comparison, the Suc2pmyc-Pom34p and Pom34p-Suc2pmyc fusion proteins both migrated with a predicted mass of ∼93 kDa. Strikingly, their status was not sensitive to Endo H treatment (Figure 1C, lanes 5–8). Therefore the Suc2p domain was not glycosylated when fused at either the N or the C terminus of Pom34p. This suggested that both N- and C-terminal regions of Pom34p are exposed to the cytoplasm.

On the basis of the above results, we speculated that Pom34p might adapt a double-pass membrane protein topology (Figure 1B, type V). Pom34p contains five potential endogenous glycosylation sites, one of which is positioned between the putative TM1 and TM2. However, there was no apparent molecular mass change after Endo H treatment of cell lysates from a pom34Δ strain expressing myc-POM34 (Figure 1D, lanes 1 and 2). To directly test whether the loop region between the two predicted TMs was positioned in the ER/NE lumen, we generated four consensus glycoslation sites in the loop region between TM1 and TM2 by site-directed mutagenesis. Each was based on the consensus asparagine–any residue–serine/threonine (NXS/T) (Kornfeld and Kornfeld 1985). Complementation of synthetic lethal pom34Δ double mutants (see below) confirmed that the resulting myc-Pom34p-(NXS/T)4 was functional (data not shown). When expressed in pom34Δ cells, the myc-Pom34p-(NXS/T)4 protein had a larger apparent molecular mass than myc-Pom34p. Moreover, the myc-Pom34p-(NXS/T)4 migration was sensitive to Endo H treatment as reflected by the decrease in molecular mass in Figure 1D between lanes 3 and 4. Taken together, these results are consistent with the double-pass model for Pom34p topology, where the N- and the C-terminal regions on the pore/cytosol side and the loop region between TM1 and TM2 localized in the ER/NE lumen.

To examine if the Pom34p fusion proteins were targeted to the membrane, alkaline extraction experiments were performed. Cell lysates from pom34Δ strains expressing different fusions were extracted with 0.1 m sodium carbonate (pH 11), and supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions were separated by centrifugation and analyzed by immunoblotting. All the Pom34p topology reporter proteins were resistant to extraction and remained associated with the pellet fraction in a manner similar to the integral membrane protein control Snl1p. In contrast, the peripheral nucleoporin Nup145C was extracted (Figure 1E). We also tested the role of each of the two transmembrane segments in targeting Pom34p to the membrane. In-frame internal deletions of the sequence encoding each respective transmembrane segment were constructed in the context of a Pom34p–Protein A (PrA) C-terminal fusion. This resulted in TM1Δ-PrA (amino acids 62–85 deleted) and TM2Δ-PrA (amino acids 129–153 deleted). The mutants were expressed in a pom34Δ strain, cell lysates were prepared, and alkaline extraction experiments were conducted. The wild-type Pom34p-PrA was exclusively present in the pellet fraction (Figure 1F). In contrast, both TM1Δ-PrA and TM2Δ-PrA were extracted from the membrane/pellet fraction and found in the supernatant. We concluded that the membrane integration of Pom34p is dependent on both transmembrane segments.

The pom34Δ pom152Δ double mutant has no growth or morphology defects:

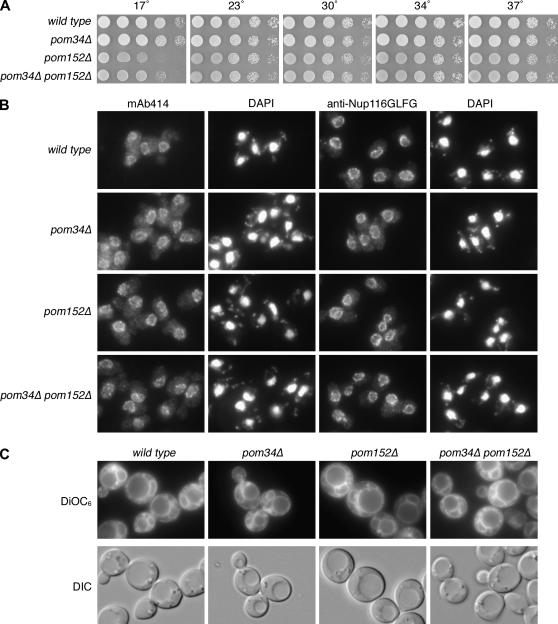

To date, Pom34p and Pom152p are the only integral membrane proteins known to localize exclusively to the NPC in S. cerevisiae. Since each is encoded by a nonessential gene (Wozniak et al. 1994; Glaever et al. 2002), we generated a double null strain and tested the viability and growth of cells lacking both of these Poms. In comparison to wild-type or single-mutant strains, the pom34Δ pom152Δ cells had no apparent growth defect when tested at a range of temperatures from 23° to 37° (Figure 2A). At 17°, the pom152Δ mutant was slightly cold sensitive, as was the pom34Δ pom152Δ mutant. To directly examine nucleoporin localization and general NPC structure, indirect immunofluorescence microscopy was performed for staining with mouse monoclonal mAb414 and rabbit affinity-purified anti-Nup116GLFG antibodies. These two antibodies both recognize epitopes in nucleoporins that harbor phenylalanine–glycine (FG) repeats (Davis and Blobel 1986; Bucci and Wente 1998). In wild-type cells, the FG Nups exhibit concentrated, punctate nuclear rim localization (Figure 2B). The pom34Δ pom152Δ double-mutant staining was identical to that of wild type. To evaluate the cellular membranes, cells in log phase growth were stained with a lipophilic fluorescent dye DiOC6. DiOC6 has been routinely used to assess intracellular membrane proliferation, including that from the ER/NE (Koning et al. 1993). The staining in pom34Δ pom152Δ cells was not different from that in wild type (Figure 2C). Overall, no defects in cell growth, NPC localization, or membrane structures were detected in pom34Δ pom152Δ cells.

Figure 2.

The pom34Δ pom152Δ double mutant has no significant growth or morphological defects. (A) Fivefold serial dilutions of equal cell numbers from wild type (SWY518), pom34Δ (SWY2565), pom152Δ (PMY17), or pom34Δ pom152Δ (SWY3093) strains were spotted on YPD medium. Growth was compared after incubation at the designated temperature. (B) Indirect immuofluorescence microscopy was performed as described in materials and methods with either mouse monoclonal mAb414 or rabbit anti-Nup116GLFG antibodies. Nuclei were detected by DAPI staining. (C) Direct fluorescence microscopy of live cells stained with DiOC6 to visualize membranes. Corresponding DIC pictures are shown.

The pom34Δ mutant has genetic interactions with a specific subset of mutants in genes encoding nucleoporins:

There are at least six major biochemically defined nucleoporin subcomplexes in the NPC: the Nup84 subcomplex (Nup84p-Nup85p-Nup120p-Nup133p-Nup145C-Seh1p-Sec13p) (Siniossoglou et al. 1998, 2000; Lutzmann et al. 2002), the Nup82 subcomplex (Nsp1p–Nup82p-Nup159p-Nup116p-Gle2p) (Grandi et al. 1995a; Bailer et al. 1998, 2000; Belgareh et al. 1998; Hurwitz et al. 1998; Ho et al. 2000), the Nic96 subcomplex (Nic96p-Nsp1p-Nup49p-Nup57p) (Grandi et al. 1993, 1995b; Schlaich et al. 1997), the Nup188 subcomplex (Nic96p-Nup188p-Nup192p-Pom152p) (Nehrbass et al. 1996; Zabel et al. 1996; Kosova et al. 1999), the Nup170 subcomplex (Nup170p-Nup53p-Nup59p) (Marelli et al. 1998), and the Nup60-Nup2 subcomplex (Denning et al. 2001; Dilworth et al. 2001). To test for POM34 genetic interactions with genes encoding other NPC components, we assembled a full panel of selected haploid nup mutants including at least two representatives from each of these defined NPC subcomplexes. For all the strain constructions, a haploid pom34Δ mutant was mated pairwise with mutant alleles of each of the NUP genes, and the resulting heterozygous diploids were sporulated and dissected to yield double-mutant pom34Δ nup haploids. If viable double-mutant haploid strains were not obtained, a URA3/CEN plasmid harboring wild-type POM34 was transformed into the corresponding heterozygous diploids. Plasmid-rescued, double-mutant haploids were isolated and tested for growth on media containing 5-FOA. Strains that are dead in the absence of the URA3 plasmid will not grow on 5-FOA, and those were scored as synthetically lethal double mutants. All viable double-mutant haploids were tested for growth at 16.5°, 23°, 30°, 34°, and 37° on YPD media and compared with the growth of the corresponding single mutants. The results are summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Growth of pom34Δ double mutants

| Temperature

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene/strain | 16.5° | 23° | 30° | 34° | 37° | Genetic interaction |

| pom34Δ | + | + | + | + | + | |

| nup188Δ | + | + | + | + | + | Synthetic lethal |

| nup188Δ pom34Δ | − | − | − | − | − | |

| nup170Δ | + | + | + | + | + | Synthetic lethal |

| nup170Δ pom34Δ | − | − | − | − | − | |

| nup59Δ | + | + | + | + | + | Synthetic lethal |

| nup59Δ pom34Δ | − | − | − | − | − | |

| gle2Δ | + | + | + | + | − | Synthetic lethal |

| gle2Δ pom34Δ | − | − | − | − | − | |

| nup159-1 (rat7-1) | + | + | + | + | − | Synthetic lethal |

| nup159-1 pom34Δ | − | − | − | − | − | |

| nup82-3 (nle4-1) | + | + | + | + | − | Synthetic lethal |

| nup82-3 pom34Δ | − | − | − | − | − | |

| nup120Δ | + | + | + | + | − | Enhanced lethality |

| nup120Δ pom34Δ | + | + | + | − | − | |

| nup116Δ | + | + | + | + | − | Enhanced lethality |

| nup116Δ pom34Δ | + | + | + | − | − | |

| nup57-E17 | + | + | + | + | − | Enhanced lethality |

| nup57-E17 pom34Δ | + | + | + | − | − | |

Strains showing no enhanced growth defect in pom34Δ double mutants included nup2Δ, nup42Δ, nup100Δ, nup145ΔN, nup60Δ, nic96-1, nup53Δ, nup157Δ, nup1Δ, nup133Δ, seh1Δ, nup145-L2, and gle1-2. All synthetic lethal strains were rescued by a URA3/CEN plasmid carrying a wild-type copy of POM34, with lethality confirmed on 5-FOA media. All double-mutant strains were tested on YPD medium. +, growth at the indicated temperature; −, no growth at the indicated temperature.

A pom152Δ synthetic lethal screen by Wozniak and coworkers identified four nup mutants that require POM152 for viability: nup59-40, nup170-21, nup188-4, and nic96-7 (Aitchison et al. 1995; Nehrbass et al. 1996). We speculated that POM34 might have genetic interactions with the same NUP genes as POM152. Consistent with our hypothesis, pom34Δ shared most of the same synthetic lethal interactions reported for pom152Δ, including lethality with nup59Δ, nup170Δ, and nup188Δ. In addition, we identified three other mutants that were lethal in the pom34Δ genetic background: nup82-3 (nle4-1), nup159-1 (rat7-1), and gle2Δ. In some cases, the double mutants were viable but had conditional growth phenotypes at temperatures permissive for the respective single-mutants' growth. Enhanced lethality defects were detected when pom34Δ was combined with nup120Δ, nup116Δ, or nup57-E17 mutants. Notably, we did not detect genetic interactions with the nup alleles corresponding to nucleoporins localized exclusively to the nucleoplasmic NPC face (Nup1p, Nup2p, Nup60p) (Rout et al. 2000). These results revealed that POM34 genetically interacts with a wide range of NUPs representing multiple distinct NPC subcomplexes.

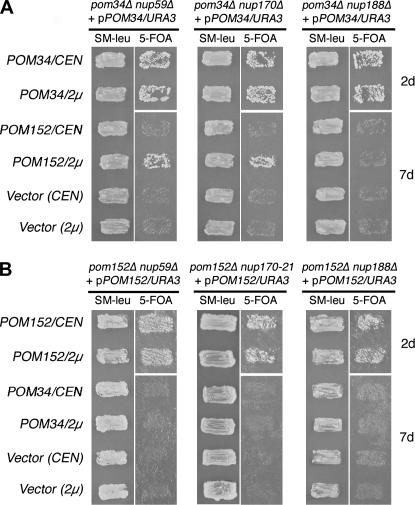

POM152 overexpression partially suppresses the loss of POM34 function:

The overlapping synthetic lethal profile for pom34Δ and pom152Δ mutants suggested that the two proteins might have common function(s). Thus, we investigated whether overexpressing one would rescue the viability of a synthetic lethal combination for the other. Double-mutant pom nup strains that required the respective POM/URA3 plasmid for viability were transformed with a high-copy plasmid (LEU2/2μ) harboring wild-type POM34 or POM152. The resulting yeast transformants were grown on SM–leu to maintain the high-copy LEU2/2μ plasmid and then assayed for colony formation after replica plating to media containing 5-FOA. If the LEU2 plasmid rescued the mutant, the strain would be viable in the absence of the URA3 plasmid and grow in the presence of 5-FOA. As controls, an empty LEU2 plasmid did not rescue growth (Figure 3). Overexpressing POM34 did not rescue any of the pom152Δ nup mutants (Figure 3B). However, the pom34Δ nup59Δ and pom34Δ nup170Δ double mutants were viable with the POM152/LEU2/2μ plasmid (Figure 3A). This suggested that overexpressing POM152 suppressed the loss of POM34 in the nup59Δ and nup170Δ genetic backgrounds. The suppression was, however, partial as reflected by diminished growth compared to the strains with a POM34/LEU2 plasmid. In addition, overexpressing POM152 did not complement the pom34Δ nup188Δ mutant. We concluded that these two integral membrane proteins have some level of functional redundancy but are not completely interchangeable.

Figure 3.

Multicopy suppression analysis of respective double mutants with POM34 and POM152 expression. (A) pom34Δ nup double-mutant strains harboring a POM34/URA3/CEN plasmid (SWY3139, SWY3132, and SWY3125) were transformed with POM152/LEU2/CEN (low copy), POM152/LEU2/2μ (high copy), POM34/LEU2/CEN, POM34/LEU2/2μ, or empty vectors. The resulting strains were patched on SM-leu and grown at 30° for 2 days before replica plating to 5-FOA medium. The cells on 5-FOA were incubated at 30° for 2 or 7 days (d). (B) pom152Δ nup double-mutant strains harboring a POM152/URA3/CEN plasmid (SWY3488, psl21, SWY3219) were transformed with the same LEU2 plasmids, patched, and grown as in A.

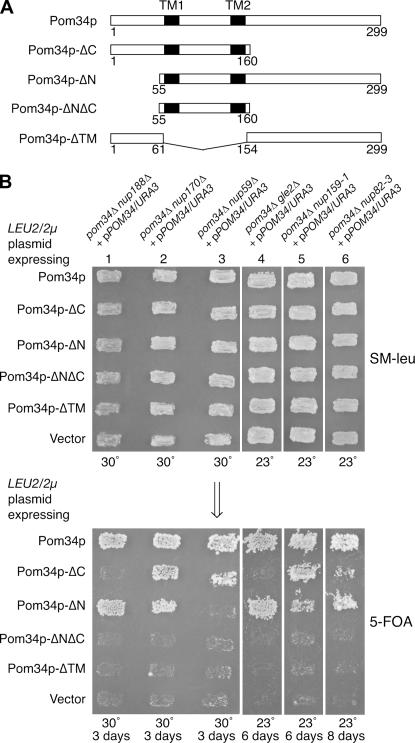

N- and C-terminal domains of Pom34p are required for distinct NPC subcomplexes:

On the basis of the topology analysis, the two transmembrane segments divide Pom34p into at least three distinctive domains: the cytosolic/pore N- and C-terminal regions and the lumenal loop region. To evaluate which of these regions are required for function, a panel of deletion/truncation mutants was generated (Figure 4A). Plasmids expressing the respective deletion mutants were transformed into six synthetic lethal double-mutant strains that require wild-type POM34/URA3/CEN for viability. Functional complementation was assayed by replica plating from SM–leu to media containing 5-FOA. Deletion of both the N- and the C-terminal regions (Pom34p-ΔNΔC) or an internal deletion of both transmembrane spans and the lumenal loop region (Pom34p-ΔTM) abolished function in all the double-mutant strains tested (Figure 4B). In contrast, production of the Pom34p-ΔN or Pom34p-ΔC deletions complemented the nup170Δ, nup159-1 (rat7-1), and nup82-3 (nle4-1) double-mutant strains when expressed from high-copy LEU2/2μ plasmids (Figure 4B, columns 2, 5, and 6) but not from low-copy LEU2/CEN plasmids (data not shown). This high-copy suppression of some double-mutant combinations suggested that the N- or the C-terminal region could replace its opposite end in some, but not all, functions. Interestingly, the production of Pom34p-ΔC and Pom34p-ΔN also showed allele-specific complementation. Pom34p-ΔC did not rescue the viability of pom34Δ nup188Δ and pom34Δ gle2Δ mutants whereas Pom34p-ΔN did (Figure 4B, columns 1 and 4). Furthermore, Pom34p-ΔN did not support growth of the pom34Δ nup59Δ strain (Figure 4B, column 3) whereas Pom34p-ΔC did. Thus, the N-terminal region was required in the nup59Δ cells and the C-terminal region in nup188Δ and gle2Δ cells. Overall, these complementation results reveal possible distinct functions for the N- and the C-terminal Pom34p regions with particular peripheral Nups in the NPC.

Figure 4.

Functional analysis of Pom34p domains. (A) Schematics of the Pom34p structural regions and related deletion/truncation polypeptides are shown. (B) Synthetic lethal double mutants harboring a POM34/URA3/CEN plasmid (low copy) were transformed with the wild-type POM34/LEU2/2μ plasmid, the respective mutant pom34/LEU2/2μ plasmids (high copy), and empty vector. Transformants were patched on SM-leu (top) at 30° (lanes 1–3) or 23° (lanes 4–6) for 2 days and then replica plated onto 5-FOA media (bottom) and incubated for the indicated days at the same temperature.

NPC structure and function are perturbed in the pom34ΔN nup188Δ double mutant:

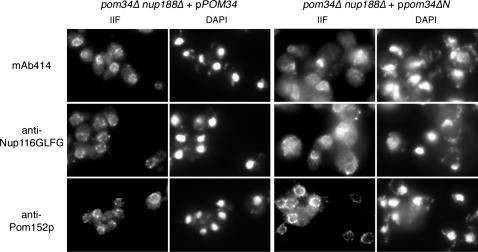

Although the viability of some pom34Δ synthetic lethal double mutants was rescued by overproduction of Pom34p-ΔN or Pom34p-ΔC, the growth rates of the complemented strains were significantly slower at all temperatures tested when compared to complementation by wild-type Pom34p (data not shown). We focused on the pom34Δ nup188Δ + ppom34ΔN/2μ strain (henceforth designated pom34ΔN nup188Δ) as it had an exacerbated growth defect at elevated temperatures. Others have reported, and we have independently tested, that the nup188Δ single mutant does not have any apparent defects in the NPC localization of FG Nups (Nehrbass et al. 1996; Zabel et al. 1996). We speculated that the slowed growth of pom34ΔN nup188Δ cells might reflect perturbations of NPC structure and function by the combined absence of the Pom34p N-terminal domain and Nup188p. To test this hypothesis, microscopy was performed to detect any defects in the pom34Δ nup188Δ mutant strain harboring either a wild-type POM34 or a mutant pom34ΔN/LEU2/2μ plasmid. Thin-section electron microscopy showed no ultrastructural abnormalities in the pom34Δ nup188Δ cells complemented with either wild-type Pom34p or Pom34p-ΔN (data not shown). To evaluate possible effects on individual Nup localization, indirect immunofluorescence microscopy was conducted with these same strains. Fixed yeast cells were labeled with mouse monoclonal antibodies recognizing FG Nups (mAb414), affinity-purified rabbit anti-Nup116GLFG antibodies, or mouse monoclonal anti-Pom152p antibodies (mAb118C3). In pom34Δ nup188Δ cells harboring the wild-type POM34 plasmid, the fluorescence staining for all three antibodies was predominantly confined to the nuclear rim in a punctate pattern (Figure 5, left column). The anti-Pom152p staining in the pom34ΔN nup188Δ cells was similar to that in the POM34 complemented strain (Figure 5, bottom right). However, the FG and GLFG staining in the majority of the pom34ΔN nup188Δ cells was no longer concentrated at the nuclear rim. Instead, most of the signal was diffuse throughout the cytoplasm and in some cases appeared as cytoplasmic foci (Figure 5, top right and middle right). Overproduction of Pom34p-ΔN in wild-type cells or in a nup188Δ single mutant had no effect on FG or GLFG staining (data not shown). In addition, GFP-tagged Nup145Cp, Nup159p, Nup188p, and Pom152p were not displaced from the NPC when Pom34p-ΔN was expressed in otherwise wild-type cells (data not shown). These results suggested that a subset of the NPC proteins, the FG Nups, was specifically mislocalized in the absence of Nup188p and the N-terminal region of Pom34p.

Figure 5.

FG Nups mislocalize in the pom34ΔN nup188Δ mutant strain. Cells in early log phase were processed for indirect immunofluorescence microscopy with mouse monoclonal mAb414, rabbit anti-Nup116GLFG, or mouse monoclonal mAb118C3 (anti-Pom152p) antibodies. Nuclei were detected by DAPI staining.

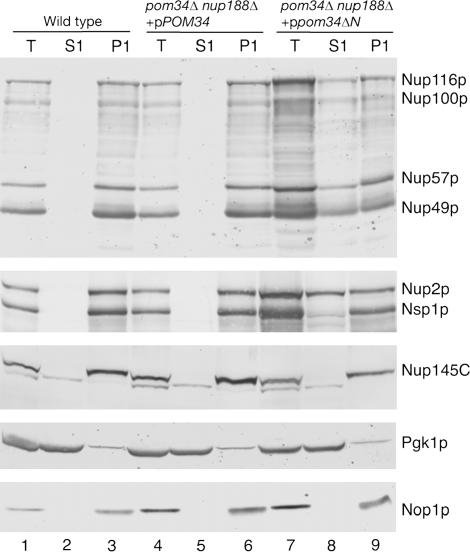

To further characterize the FG Nup mislocalization phenotype, subcellular fractionation was conducted with lysates from wild-type, pom34Δ nup188Δ + pPOM34, and pom34ΔN nup188Δ strains. Total crude cell lysates were separated by centrifugation into S1 and P1 fractions. Samples of the fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting with controls for cytoplasmic (anti-Pgk1p) and nuclear (anti-Nop1p) proteins that fractionate in the S1 and the P1, respectively. Immunoblotting was used to monitor the Nup fractionation with anti-Nup116GLFG detecting four GLFG Nups, anti-Nsp1p recognizing both Nup2p and Nsp1p, and anti-Nup145C for a non-FG polypeptide. In fractions from the wild-type and the pom34Δ nup188Δ + pPOM34 cells, all the Nups were predominantly distributed in the P1 fraction (Figure 6, lanes 1–6). In contrast, the distribution of FG Nups in the S1 and P1 fractions was quite different in lysates from the pom34ΔN nup188Δ mutant. Significant fractions of Nup116p, Nup100p, Nup57p, Nup49p, and Nup2p were recovered in the S1 fraction (Figure 6, lanes 7–9). Interestingly, the effect on Nsp1p was not as dramatic as for the above FG Nups, with the majority of Nsp1p still in the P1 fraction. Nup145C also was not changed and was exclusively in the P1 fraction. Taken together, these data suggested that a specific subset of Nups is perturbed in the pom34ΔN nup188Δ, resulting in diminished NPC localization.

Figure 6.

Subcellular fractionation of the pom34ΔN nup188Δ mutant shows increased levels of FG Nups in the cytoplasm. Spheroplast lysates from wild type (SWY518), pom34Δ nup188Δ + pPOM34 (SWY3489), and pom34Δ nup188Δ + ppom34ΔN (SWY3490) were prepared and separated into soluble (S1) and insoluble pellet (P1) fractions at a low speed centrifugation. Fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting with rabbit anti-Nup116GLFG, rabbit anti-Nsp1p, rabbit anti-Nup145C, mouse monoclonal mAb22C5 (anti-cytoplasmic protein Pgk1p), and mouse monoclonal mAb D77 (anti-nucleolar protein Nop1p) antibodies. The anti-Nup116GLFG antibody recognizes Nup116p, Nup100p, Nup57p, and Nup49p. The anti-Nsp1p antibody recognizes Nup2p in addition to Nsp1p.

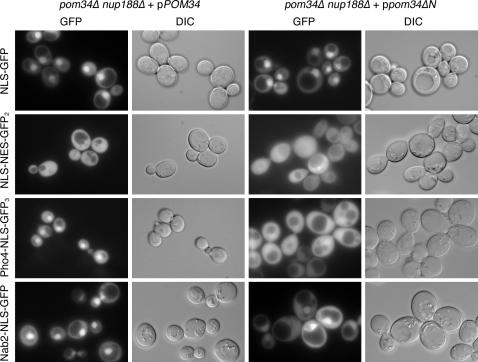

To directly test the role of Pom34p in NPC function, we conducted nucleocytoplasmic transport assays. A series of green fluorescence protein (GFP)-conjugated reporters harboring nuclear localization sequences (NLS) and/or nuclear export sequences (NES) for distinct transport pathways were expressed in the cells. These included cNLS-GFP for Kap60p–Kap95p import, Nab2-NLS-GFP for Kap104p import, Pho4-NLS-GFP3 for Kap121p (Pse1p) import, and NLS-NES-GFP2 for shuttling by Kap60p-Kap95p import and Xpo1p (Crm1p, Kap124p) export (as reviewed in Chook and Blobel 2001). The steady-state localizations for the GFP-reporters were examined by direct fluorescence microscopy (Figure 7). All three import reporters showed nuclear accumulation in the control pom34Δ nup188Δ + pPOM34 strain, and the shuttling NLS-NES-GFP2 also had no detectable perturbations and showed steady-state cytoplasmic localization (Figure 7, left column). The steady-state localizations of cNLS-GFP and NLS-NES-GFP2 in the pom34ΔN nup188Δ mutant cells were similar to that in the complemented pom34Δ nup188Δ + pPOM34 double mutant (Figure 7, first and second rows, respectively). However, in the pom34ΔN nup188Δ mutant cells, the steady-state nuclear levels of Pho4-NLS-GFP3 were significantly altered with increased cytoplasmic localization and markedly diminished nuclear accumulation (Figure 7, third row, right column). There was a similar, although less severe, change in Nab2-NLS-GFP with increased cytoplasmic localization. This indicated import defects in karyopherin transport pathways. Thus, specific FG Nups and transport pathways were perturbed in the pom34ΔN nup188Δ mutant cells.

Figure 7.

Analysis of nucleocytoplasmic transport in the pom34ΔN nup188Δ mutant reveals defects in Kap121p and Kap104p import. Cells growing at 30° in early log phase were visualized by direct fluorescence microscopy for steady-state localization of GFP fluorescence. The four GFP reporters analyzed include NLS-GFP (for Kap95p import), NLS-NES-GFP2 (for Xpo1p export), Pho4-NLS-GFP3 (for Kap121p), and Nab2-NLS-GFP (for Kap104p). The corresponding DIC images are shown.

DISCUSSION

To gain insight into the function of nuclear pore membrane proteins, we have conducted experiments to define the Pom34p membrane topology and address the Pom34p functional relationship with Nups. We provide evidence here that Pom34p is important in maintaining normal NPC architecture and function. Our topology studies show that Pom34p is a double-pass transmembrane protein with both N- and C-terminal regions exposed to the cytosol/pore. Further analysis reveals roles for the Pom34p N- and C-terminal regions with specific peripheral Nups. We also document perturbations in the NPC association of FG Nups and nuclear transport in a pom34ΔN nup188Δ mutant. These results provide further insight into the roles for membrane proteins in the structural organization of the NPC.

We have found that Pom34p inserts with a hairpin-like structure into the nuclear membrane, effectively generating multiple functional domains: a cytosolic/pore N-terminal domain, a cytosolic/pore C-terminal domain, a lumenal loop domain, and two transmembrane domains (TM1 and TM2). As commonly observed in other integral membrane proteins, positively charged amino acid residues are positioned at the cytoplasmic sides flanking both hydrophobic transmembrane domains (Mulugeta and Beers 2003). Our results suggest that the multiple Pom34p domains are independently necessary for its function. First, we note that both TM1 and TM2 are required for Pom34p membrane integration (Figure 1). Most multipass transmembrane proteins rely on the first transmembrane domain for membrane insertion and anchoring; however, the process can be more complicated (Rapoport et al. 2004). The requirement for both transmembrane regions to direct and/or anchor Pom34p into membranes might indicate that the two TMs work cooperatively during translocation into the NE/ER membrane. Structural analysis of the archaebacterium protein-conducting channel suggests that two TMs can be accommodated at one time in the ER Sec61 channel (Rapoport et al. 2004; Van den berg et al. 2004). Alternatively, both TMs might be required for stable membrane association. Second, the lumenal loop region might form a second, necessary, functional domain that appears to be essential for Pom34p stability. Proteins from deletion constructs that encoded the N-terminal domain plus TM1, the C-terminal domain plus TM2, or an internal deletion of the loop region could not be detected by Western analysis (data not shown). Finally, the N-terminal and C-terminal domains have nonoverlapping functions, as their ability to complement the different pom34Δ double mutants differs (Figure 4). This suggests that protein–protein interactions on the cytosolic/pore side are important for Pom34p function.

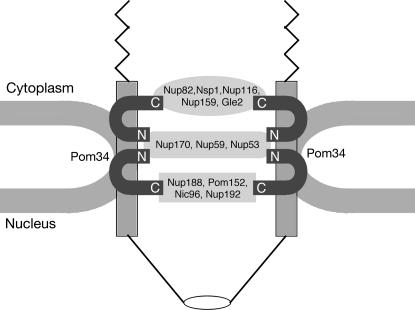

The Pom34p N- and C-terminal regions may have distinct protein–protein interaction partners in the NPC. The schematic model shown in Figure 8 incorporates our findings with the insights from prior NPC structural analyses. Extensive prior biochemical studies have characterized NPC subcomplexes with distinct nucleoporin compositions (reviewed in Suntharalingam and Wente 2003). Each subcomplex might represent a specific substructure of the NPC architecture. Our genetic studies have linked POM34 with genes encoding Nups in the Nup84, Nup188, Nup170, and Nup82 subcomplexes. The complementation analysis with pom34 deletion mutants indicates specific connections for (1) the Nup170 subcomplex with the Pom34p N domain and (2) the Nup188 subcomplex and the Nup82 subcomplex with the Pom34p C domain. The Nup170 subcomplex and Nup188 subcomplex are both symmetrically localized in the NPC with respect to the NE (Rout et al. 2000). These two subcomplexes are thought to form a fundamental NPC framework as evidenced by an extensive genetic and biochemical interaction network among their components (Aitchison et al. 1995; Nehrbass et al. 1996; Zabel et al. 1996; Marelli et al. 1998). In contrast, the Nup82 subcomplex is localized exclusively on the cytoplasmic NPC face (Rout et al. 2000). The model depicted in Figure 8 also takes into account estimates of the Pom34p stoichiometry being at least twice that of Pom152p and Ndc1p (Rout et al. 2000). Overall, Pom34p might be a central hub at the core of the pore and serve to assist in anchoring different NPC subcomplexes to the NE.

Figure 8.

Model for Pom34p in NPC structural organization. The schematic diagram is based on information from published biochemical studies and the results in this article. Connections are shown between the N-terminal region of Pom34p and the Nup170 subcomplex and between the C-terminal Pom34p region and both the Nup188 subcomplex and the Nup82 subcomplex. Pom34p, the Nup170 subcomplex, and the Nup188 subcomplex are all found symmetrically localized on both faces of the NPC (Rout et al. 2000). The predicted relative stoichiometries of Pom34p and the Nup170 subcomplex are 32 copies/NPC vs. 16 copies/NPC for the Nup188 subcomplex (Rout et al. 2000). Nic96p and Nsp1p have been isolated in multiple biochemical subcomplexes and are also abundant NPC components at 32 copies/NPC [Nic96p in the Nup188 subcomplex and the Nic96 subcomplex (not shown); Nsp1p in the Nup82 subcomplex and the Nic96 subcomplex (not shown) (reviewed in Suntharalingam and Wente 2003)]. The Nup82 complex is exclusively cytoplasmic and predicted to be present in only 8 or 16 copies/NPC. Three peripheral FG Nups are shown assembled in the Nup82 subcomplex (Nsp1p, Nup116p, and Nup159p). Other FG Nups likely assemble by association with these core subcomplexes and the Nup84 subcomplex (not shown).

Recently, studies on the molecular evolution of the NPC have proposed that subunits of the Nup84 subcomplex are structurally related to transport vesicle coat proteins. It has been suggested that this similarity could indicate a common function in membrane deformation wherein the Nup84 subcomplex contributes to the stabilization of the membrane curvature at the nuclear pore in much the same way that coat proteins contribute to membrane budding during vesicular transport (Devos et al. 2004; Mans et al. 2004). However, neither the Nup84 subcomplex nor its vertebrate ortholog, the Nup107–160 subcomplex, has been previously connected to the integral membrane proteins or the nuclear membrane (Antonin and Mattaj 2005). The enhanced lethality observed in the pom34Δ nup120Δ double mutant provides the first evidence that the Nup84 subcomplex is intimately linked to the pore membrane.

Our genetic results suggest that the global NPC structure is weakened in the absence of both one cytoplasmic/pore domain of Pom34p (the N- or the C-terminal region) and one major soluble Nup. The pom34ΔN nup188Δ double mutant has perturbations in the function of specific FG Nups. Our immunofluorescence microscopy and biochemical fractionation results document the cytoplasmic mislocalization of at least five FG Nups: Nup116p, Nup100p, Nup57p, Nup49p, and Nup2p. Interestingly, Nsp1p is not significantly altered. Diminished FG Nup function in the pom34ΔN nup188Δ double mutant is also reflected by a defect in karyopherin nuclear transport pathways. Whereas Kap95p and Xpo1p transport is not changed at steady state in the pom34ΔN nup188Δ mutant, we observe specific inhibition of the Kap121p and Kap104p transport pathways. This transport phenotype correlates directly with results from our recent study of FG Nup function (Strawn et al. 2004). We found that Kap121p and Kap104p import is more sensitive than Kap95p import to deletions of the FG domains. For example, a nup100ΔGLFG nup49ΔGLFG nup57ΔGLFG mutant has robust Kap95p import but a markedly diminished capacity for Kap104p import (Strawn et al. 2004). Taken together, this suggests a role for Pom34p either in maintaining the association of FG Nups in NPCs or in the assembly of FG Nups into new NPCs.

In the NPC architecture, the FG Nups are assembled into the NPC by associations with Nup82p (including Nsp1p, Nup116p, and Nup159p) and Nic96p (including Nsp1p, Nup49p, and Nup57p) and by potential connections between Nup42p, Nup57p, and Nup145N to the Nup84 subcomplex (Grandi et al. 1995a; Bailer et al. 1998, 2000; Belgareh et al. 1998; Hurwitz et al. 1998; Ho et al. 2000; Rout et al. 2000; Allen et al. 2001; Lutzmann et al. 2005). There is no evidence that Pom34p interacts directly with an FG Nup. In the pom34ΔN nup188Δ mutant, we predict that the FG Nups are perturbed via a secondary effect on the Nup170 and the Nup188 subcomplexes that are anchored in part by Pom34p (Figure 8).

As described in the Introduction, there are striking differences in Pom composition between vertebrates and fungi. However, the Poms likely share common roles across species in stabilizing the assembled core structure of the intact NPC by interacting with soluble structural Nups. We predict that the Pom compositional distinctions are linked to the contrasting mitotic mechanisms across species. During the open mitosis of vertebrates, the NE fragments and the NPC disassembles at the beginning of mitosis followed by reassembly in anaphase (Burke and Ellenberg 2002). Recent work in Aspergillus nidulans has shown that during its closed mitosis several FG Nups are disassembled from the NPC and nuclear transport is altered (De Souza et al. 2004). However, during mitosis, the Aspergillus POM152 homolog and the structural non-FG peripheral Nups tested maintain their NE and likely NPC association. Interestingly, our pom34ΔN nup188Δ mutant shows decreased association of some of the same FG Nups and diminished nuclear transport by specific karyopherins. This suggests that there may be features of Pom152p and Pom34p that are critical for maintaining the pore/NE and anchorage of the major structural Nups during a closed mitosis. As such, the Poms may form the mechanistic basis for the differences between NPC dynamics in vertebrate and budding yeast cells.

In S. cerevisiae, we have found that the pattern of genetic connections for POM34 and POM152 with NUPs is quite similar. Like Pom34p, Pom152p has genetic and physical connections with components of the Nup170 and the Nup188 subcomplexes (Aitchison et al. 1995; Nehrbass et al. 1996). Pom34p and Pom152p also have some level of functional overlap based on our genetic suppression results (Figure 3). Despite a potential complementary role for Pom34p and Pom152p in NPC structural maintenance, it is intriguing that the pom34Δ pom152Δ double mutant is viable and shows no detectable NPC defects. Moreover, overexpression of POM152 rescued the lethality of certain pom34Δ nup double mutants whereas overexpression of POM34 did not rescue any of the tested pom152Δ nup mutants. Although we do not know if the respective POM overexpression levels are comparable, this suggests that Pom152p has a function distinct from Pom34p. In addition, the pom34Δ nic96-1 mutant showed no enhanced lethality whereas a pom152Δ nic96-7 mutant is synthetically lethal (Aitchison et al. 1995; Tcheperegine et al. 1999). This might reflect allele specificity for the nic96 mutants, and/or these results might be further evidence of distinct roles for Pom152p and Pom34p. Work revealing the direct physical interaction partners for Pom152p and Pom34p will be needed to further resolve their distinct and shared functions.

Extensive NPC-specific proteomics studies have revealed only one other S. cerevisiae pore membrane protein, Ndc1p (Rout et al. 2000). NDC1 might compensate for the loss of both POM34 and POM152 in the double null strain. NPC structure in budding yeast is also influenced by several integral membrane proteins that are not specifically or exclusively localized at NPCs. Mutations in the genes encoding the NE/ER membrane proteins Brr6p, Spo7p, and Nem1p have synthetic lethal interactions with peripheral Nups, as well as perturb NE morphology and the incorporation of Nups into the NPC (Siniossoglou et al. 1998; de Bruyn Kops and Guthrie 2001). Snl1p is a membrane-anchored Bag domain cochaperone that might recruit Hsp70p to the NE/ER and assist with Nup folding and assembly (Ho et al. 1998; Sondermann et al. 2002). The involvement of nonsubunit assembly factors has been well established in the biosynthesis of another macromolecular machine, the vacuolar H+-ATPase complex (Graham and Stevens 1999). We speculate that multiple integral membrane proteins, either within the nuclear pore domain or in the NE, execute coordinated functions in NPC assembly and function. Future studies will be required to identify the key integral membrane proteins that mediate NPC assembly into the intact NE in closed mitotic organisms and during interphase of all eukaryotic cells.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the following colleagues for generously sharing yeast strains, plasmids, and/or antibodies: John Aris, Günter Blobel, Mirella Bucci, Charles Cole, Laura Davis, David Goldfarb, Kathy Gould, Ed Hurt, Erin O'Shea, Michael Rout, Karsten Weis, and Rick Wozniak. We thank the Wente laboratory members for valuable comments on the manuscript and critical discussions. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, R01 GM-57438, to S.R.W.

References

- Aitchison, J. D., M. P. Rout, M. Marelli, G. Blobel and R. W. Wozniak, 1995. Two novel related yeast nucleoporins Nup170p and Nup157p: complementation with the vertebrate homologue Nup155p and functional interactions with the yeast nuclear pore-membrane protein Pom152p. J. Cell Biol. 131: 1133–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, N. P., L. Huang, A. Burlingame and M. Rexach, 2001. Proteomic analysis of nucleoporin interacting proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 29268–29274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T. D., J. M. Cronshaw, S. Bagley, E. Kiseleva and M. W. Goldberg, 2000. The nuclear pore complex: mediator of translocation between nucleus and cytoplasm. J. Cell Sci. 113: 1651–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonin, W., and I. W. Mattaj, 2005. Nuclear pore complexes: round the bend? Nat. Cell Biol. 7: 10–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonin, W., C. Franz, U. Haselmann, C. Antony and I. W. Mattaj, 2005. The integral membrane nucleoporin pom121 functionally links nuclear pore complex assembly and nuclear envelope formation. Mol. Cell 17: 83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aris, J. P., and G. Blobel, 1988. Identification and characterization of a yeast nucleolar protein that is similar to a rat liver nucleolar protein. J. Cell Biol. 107: 17–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailer, S. M., S. Siniossoglou, A. Podtelejnikov, A. Hellwig, M. Mann et al., 1998. Nup116p and Nup100p are interchangeable through a conserved motif which constitutes a docking site for the mRNA transport factor Gle2p. EMBO J. 17: 1107–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailer, S. M., C. Balduf, J. Katahira, A. Podtelejnikov, C. Rollenhagen et al., 2000. Nup116p associates with the Nup82p-Nsp1p-Nup159p nucleoporin complex. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 23540–23548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudin, A., O. Ozier-Kalogeropoulos, A. Denouel, F. Lacroute and C. Cullin, 1993. A simple and efficient method for direct gene deletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 21: 3329–3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, M., F. Forster, M. Ecke, J. M. Plitzko, F. Melchior et al., 2004. Nuclear pore complex structure and dynamics revealed by cryoelectron tomography. Science 306: 1387–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belanger, K. D., M. A. Kenna, S. Wei and L. I. Davis, 1994. Genetic and physical interactions between Srp1p and nuclear pore complex proteins Nup1p and Nup2p. J. Cell Biol. 126: 619–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belanger, K. D., L. A. Simmons, J. K. Roth, K. A. VanderPloeg, L. B. Lichten et al., 2004. The karyopherin Msn5/Kap142 requires Nup82 for nuclear export and performs a function distinct from translocation in RPA protein import. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 43530–43539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgareh, N., C. Snay-Hodge, F. Pasteau, S. Dagher, C. N. Cole et al., 1998. Functional characterization of a Nup159p-containing nuclear pore subcomplex. Mol. Biol. Cell 9: 3475–3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodoor, K., S. Shaikh, D. Salina, W. H. Raharjo, R. Bastos et al., 1999. Sequential recruitment of NPC proteins to the nuclear periphery at the end of mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 112: 2253–2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci, M., and S. R. Wente, 1997. In vivo dynamics of nuclear pore complexes in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 136: 1185–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci, M., and S. R. Wente, 1998. A novel fluorescence-based genetic strategy identifies mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae defective for nuclear pore complex assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 9: 2439–2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, B., and J. Ellenberg, 2002. Remodeling the walls of the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3: 487–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chial, H. J., M. P. Rout, T. H. Giddings and M. Winey, 1998. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ndc1p is a shared component of nuclear pore complexes and spindle pole bodies. J. Cell Biol. 143: 1789–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chook, Y. M., and G. Blobel, 2001. Karyopherins and nuclear import. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11: 703–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson, T. W., R. S. Sikorski, M. Dante, J. H. Shero and P. Hieter, 1992. Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene 110: 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronshaw, J. M., A. N. Krutchinsky, W. Zhang, B. T. Chait and M. J. Matunis, 2002. Proteomic analysis of the mammalian nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 158: 915–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L. I., and G. Blobel, 1986. Identification and characterization of a nuclear pore complex protein. Cell 45: 699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruyn Kops, A., and C. Guthrie, 2001. An essential nuclear envelope integral membrane protein, Brr6p, required for nuclear transport. EMBO J. 20: 4183–4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning, D., B. Mykytka, N. P. Allen, L. Huang, B. Al et al., 2001. The nucleoporin Nup60p functions as a Gsp1p-GTP-sensitive tether for Nup2p at the nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 154: 937–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza, C. P., A. H. Osmani, S. B. Hashmi and S. A. Osmani, 2004. Partial nuclear pore complex disassembly during closed mitosis in Aspergillus nidulans. Curr. Biol. 14: 1973–1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos, D., S. Dokudovskaya, F. Alber, R. Williams, B. T. Chait et al., 2004. Components of coated vesicles and nuclear pore complexes share a common molecular architecture. PLoS Biol. 2: e380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth, D. J., A. Suprapto, J. C. Padovan, B. T. Chait, R. W. Wozniak et al., 2001. Nup2p dynamically associates with the distal regions of the yeast nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 153: 1465–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emtage, J. L., M. Bucci, J. L. Watkins and S. R. Wente, 1997. Defining the essential functional regions of the nucleoporin Nup145p. J. Cell Sci. 110: 911–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, C., C. Rustum and E. Hallberg, 2004. Dynamic properties of nuclear pore complex proteins in gp210 deficient cells. FEBS Lett. 572: 261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenkrog, B., and U. Aebi, 2003. The nuclear pore complex: nucleocytoplasmic transport and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4: 757–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaever, G., A. M. Chu, C. Connelly, L. Riles, S. Veronneau et al., 2002. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 418: 387–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, M. W., C. Wiese, T. D. Allen and K. L. Wilson, 1997. Dimples, pores, star-rings, and thin rings on growing nuclear envelopes: evidence for structural intermediates in nuclear pore complex assembly. J. Cell Sci. 110: 409–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, A. L., C. A. Snay, C. V. Heath and C. N. Cole, 1996. Pleiotropic nuclear defects associated with a conditional allele of the novel nucleoporin Rat9p/Nup85p. Mol. Biol. Cell 7: 917–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorsch, L. C., T. C. Dockendorff and C. N. Cole, 1995. A conditional allele of the novel repeat-containing yeast nucleoporin RAT7/NUP159 causes both rapid cessation of mRNA export and reversible clustering of nuclear pore complexes. J. Cell Biol. 129: 939–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, L. A., and T. H. Stevens, 1999. Assembly of the yeast vacuolar proton-translocating ATPase. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 31: 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandi, P., V. Doye and E. C. Hurt, 1993. Purification of NSP1 reveals complex formation with ‘GLFG’ nucleoporins and a novel nuclear pore protein NIC96. EMBO J. 12: 3061–3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandi, P., S. Emig, C. Weise, F. Hucho, T. Pohl et al., 1995. a A novel nuclear pore protein Nup82p which specifically binds to a fraction of Nsp1p. J. Cell Biol. 130: 1263–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandi, P., N. Schlaich, H. Tekotte and E. C. Hurt, 1995. b Functional interaction of Nic96p with a core nucleoporin complex consisting of Nsp1p, Nup49p and a novel protein Nup57p. EMBO J. 14: 76–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greber, U. F., A. Senior and L. Gerace, 1990. A major glycoprotein of the nuclear pore complex is a membrane-spanning polypeptide with a large lumenal domain and a small cytoplasmic tail. EMBO J. 9: 1495–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallberg, E., R. W. Wozniak and G. Blobel, 1993. An integral membrane protein of the pore membrane domain of the nuclear envelope contains a nucleoporin-like region. J. Cell Biol. 122: 513–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, A. K., G. A. Raczniak, E. B. Ives and S. R. Wente, 1998. The integral membrane protein Snl1p is genetically linked to yeast nuclear pore complex function. Mol. Biol. Cell 9: 355–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, A. K., T. X. Shen, K. J. Ryan, E. Kiseleva, M. A. Levy et al., 2000. Assembly and preferential localization of Nup116p on the cytoplasmic face of the nuclear pore complex by interaction with Nup82p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 5736–5748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz, M. E., C. Strambio-de-Castillia and G. Blobel, 1998. Two yeast nuclear pore complex proteins involved in mRNA export form a cytoplasmically oriented subcomplex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 11241–11245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imreh, G., D. Maksel, J. B. de Monvel, L. Branden and E. Hallberg, 2003. ER retention may play a role in sorting of the nuclear pore membrane protein POM121. Exp. Cell Res. 284: 173–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito, H., Y. Fukuda, K. Murata and A. Kimura, 1983. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol. 153: 163–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H., K. Melen and G. von Heijne, 2003. Topology models for 37 Saccharomyces cerevisiae membrane proteins based on C-terminal reporter fusions and predictions. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 10208–10213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning, A. J., P. Y. Lum, J. M. Williams and R. Wright, 1993. DiOC6 staining reveals organelle structure and dynamics in living yeast cells. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 25: 111–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld, R., and S. Kornfeld, 1985. Assembly of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 45: 631–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosova, B., N. Pante, C. Rollenhagen and E. Hurt, 1999. Nup192p is a conserved nucleoporin with a preferential location at the inner site of the nuclear membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 22646–22651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyte, J., and R. F. Doolittle, 1982. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157: 105–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, C. K., T. H. Giddings, Jr. and M. Winey, 2004. A novel allele of Saccharomyces cerevisiae NDC1 reveals a potential role for the spindle pole body component Ndc1p in nuclear pore assembly. Eukaryot. Cell 3: 447–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzmann, M., R. Kunze, A. Buerer, U. Aebi and E. Hurt, 2002. Modular self-assembly of a Y-shaped multiprotein complex from seven nucleoporins. EMBO J. 21: 387–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzmann, M., R. Kunze, K. Stangl, P. Stelter, K. F. Toth et al., 2005. Reconstitution of Nup157 and Nup145N into the Nup84 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 18442–18451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans, B. J., V. Anantharaman, L. Aravind and E. V. Koonin, 2004. Comparative genomics, evolution and origins of the nuclear envelope and nuclear pore complex. Cell Cycle 3: 1612–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marelli, M., J. D. Aitchison and R. W. Wozniak, 1998. Specific binding of the karyopherin Kap121p to a subunit of the nuclear pore complex containing Nup53p, Nup59p, and Nup170p. J. Cell Biol. 143: 1813–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulugeta, S., and M. F. Beers, 2003. Processing of surfactant protein C requires a type II transmembrane topology directed by juxtamembrane positively charged residues. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 47979–47986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, R., and S. R. Wente, 1996. An RNA-export mediator with an essential nuclear export signal. Nature 383: 357–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehrbass, U., H. Kern, A. Mutvei, H. Horstmann, B. Marshallsay et al., 1990. NSP1: a yeast nuclear envelope protein localized at the nuclear pores exerts its essential function by its carboxy-terminal domain. Cell 61: 979–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehrbass, U., M. P. Rout, S. Maguire, G. Blobel and R. W. Wozniak, 1996. The yeast nucleoporin Nup188p interacts genetically and physically with the core structures of the nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 133: 1153–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabut, G., V. Doye and J. Ellenberg, 2004. Mapping the dynamic organization of the nuclear pore complex inside single living cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 6: 1114–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, T. A., V. Goder, S. U. Heinrich and K. E. Matlack, 2004. Membrane-protein integration and the role of the translocation channel. Trends Cell Biol. 14: 568–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano, J. D., and S. Michaelis, 2001. Topological and mutational analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ste14p, founding member of the isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase family. Mol. Biol. Cell 12: 1957–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rout, M. P., J. D. Aitchison, A. Suprapto, K. Hjertaas, Y. Zhao et al., 2000. The yeast nuclear pore complex: composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 148: 635–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra, C. A., C. M. Hammell, C. V. Heath and C. N. Cole, 1997. Yeast heat shock mRNAs are exported through a distinct pathway defined by Rip1p. Genes Dev. 11: 2845–2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch and T. Maniatis, 1989. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.