Abstract

Background

Staphylococcus aureus or MRSA (Methicillin Resistant S. aureus), is an acquired pathogen and the primary cause of nosocomial infections worldwide. In S. aureus, teichoic acid is an essential component of the cell wall, and its biosynthesis is not yet well characterized. Studies in Bacillus subtilis have discovered two different pathways of teichoic acid biosynthesis, in two strains W23 and 168 respectively, namely teichoic acid ribitol (tar) and teichoic acid glycerol (tag). The genes involved in these two pathways are also characterized, tarA, tarB, tarD, tarI, tarJ, tarK, tarL for the tar pathway, and tagA, tagB, tagD, tagE, tagF for the tag pathway. With the genome sequences of several MRSA strains: Mu50, MW2, N315, MRSA252, COL as well as methicillin susceptible strain MSSA476 available, a comparative genomic analysis was performed to characterize teichoic acid biosynthesis in these S. aureus strains.

Results

We identified all S. aureus tar and tag gene orthologs in the selected S. aureus strains which would contribute to teichoic acids sythesis.Based on our identification of genes orthologous to tarI, tarJ, tarL, which are specific to tar pathway in B. subtilis W23, we also concluded that tar is the major teichoic acid biogenesis pathway in S. aureus. Further analyses indicated that the S. aureus tar genes, different from the divergon organization in B. subtilis, are organized into several clusters in cis. Most interesting, compared with genes in B. subtilis tar pathway, the S. aureus tar specific genes (tarI,J,L) are duplicated in all six S. aureus genomes.

Conclusion

In the S. aureus strains we analyzed, tar (teichoic acid ribitol) is the main teichoic acid biogenesis pathway. The tar genes are organized into several genomic groups in cis and the genes specific to tar (relative to tag): tarI, tarJ, tarL are duplicated. The genomic organization of the S. aureus tar pathway suggests their regulations are different when compared to B. subtilis tar or tag pathway, which are grouped in two operons in a divergon structure.

Background

Staphylococcus. Aureus (S. aureus) is a Gram-positive bacterium, which causes a variety of suppurative infections and toxinoses in humans. The death rate associated with S. aureus infection is still high even with antimicrobial drug treatments due to the development of antibiotic resistance in Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) strains. Current developments in antimicrobial therapeutics show little efficacy in treating S. aureus and this bacterium remains a major human health threat. S. aureus, and in particular its cell wall, remain a major target of glycopeptide antibiotics and focus of bacteriology research.

Teichoic acids, polymers of alternating phosphate and alditol groups, in addition to peptidoglycan are an essential component of bacterial cell walls. Teichoic acid biosynthesis in S. aureus has not been well characterized. B. subtilis and S. aureus are both phylogenetically classified into Bacillus/Staphylococcus group. Unlike that in S. aureus, the teichoic acid biogenesis in B. subtilis is well understood[1,2]. There are two major types of cell wall teichoic acid in B. subtilis, poly(glycerol phosphate) [poly(GroP)] in strain 168 [2] and poly(ribitol phosphate) [poly(RboP)] in strain W23 [3]. In strain 168, the biosynthesis of teichoic acid poly(GroP) involves genes tagA, tagB, tagD, tagE, and tagF. These tag genes are organized in a divergon of two divergently transcribed operons, tagAB and tagDEF[4,5]. In W23, the biosynthesis of teichoic acids poly(RboP) involves genes tarA, tarB, tarD, tarF, tarI, tarJ, tarK and tarL. The tar genes, similar to the tag genes, are also organized in a divergon, tagAB-tagDEF [2]. The biogenesis of essential wall teichoic acid in B. subtilis differs in these two strains, yet still shares similar enzymatic steps. Functions of tagB, tagD, tagF were identified biochemically [1,6]. Based on high sequence similarity, tarA, tarB, tarD, and tarF are believed to perform similar enzymatic reactions as tagA, tagB, tagD, and tagF do respectively [2], while tarI, tarJ, tarK and tarL carry functions specific to poly(RboP) teichoic acid biosynthesis [2].

It has been reported that S. aureus H contains ribitol in its cell wall as does B. subtilis W23 [7,8]. It has also been shown that a TarD like enzyme exists in S. aureus with catalytic characteristics different from B. subtilis TagD [9]. These studies suggest poly(RboP) could be one of the cell wall teichoic acids in some S. aureus strains, yet this has not been unequivocally demonstrated.

Recently the genomes of MRSA strains Mu50, MW2, N315, MRSA252, and COL as well as methicillin susceptible strain MSSA476 have been sequenced [9-12]. The available sequence information enables us to take a comparative genomics approach to study the genomic requirements of wall teichoic acid in S. aureus by comparing them to the genes involved in B. subtilis teichoic acid synthesis.

We took all B. subtilis tar and tag genes, computationally to identify all orthologous genes supposedly involved in wall teichoic acid biogenesis in the S. aureus strains Mu50, MW2, N315, MRSA252, MSSA476 and COL. Our results suggest that poly(RboP), rather than poly(GroP), is the major teichoic acid in these strains. We also report the genomic organization of the teichoic acid biogenesis genes, which is different from the divergon organization in B. subtilis W23 and 168.

Results

Identify genes involved in wall teichoic acid synthesis in S. aureus through comparative genomics analysis

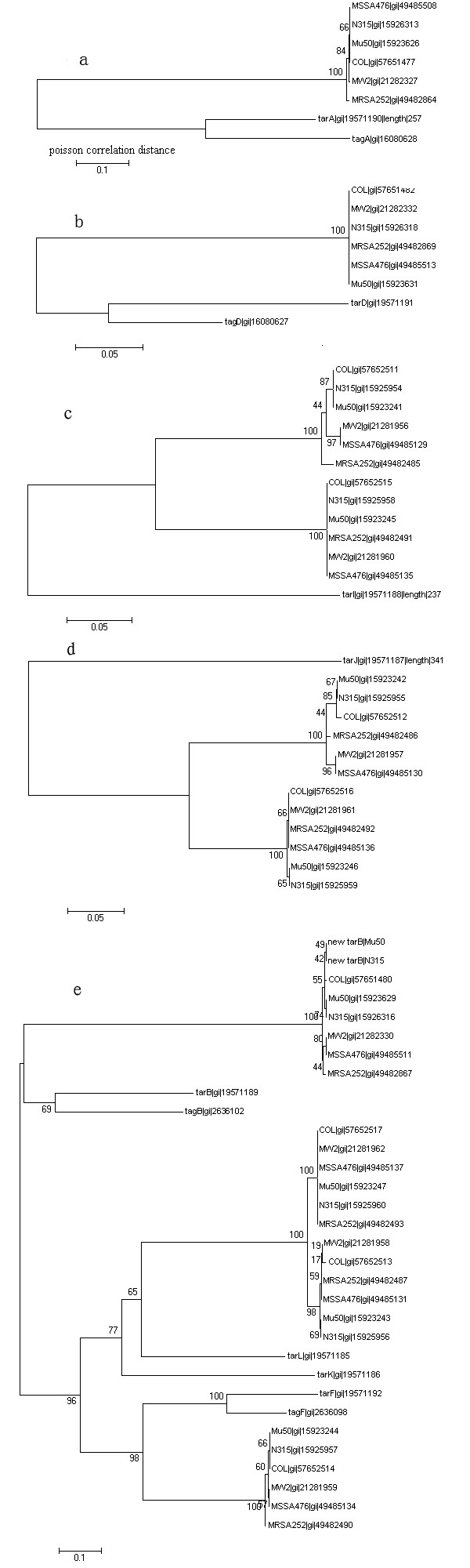

In order to identify the genes concerned with wall teichoic acids synthesis in S. aureus, strains Mu50, MW2, N315, MRSA252, MSSA476 and COL, amino acid sequences of all tar genes in B. subtilis W23 strain and tag genes in B. subtilis 168 strain from GenBank were BLASTed against the Refseq ORFs of Mu50, MW2, N315, MRSA252, MSSA476 and COL. Significant hits were identified (data not shown), and further subjected to phylogenetic analysis. The analysis led to the identification of the corresponding tar or tag orthologs in the S. aureus strains we examined. "Ortholog" here is technically defined as those with the best phylogenetic similarity. By deleting branches of less homologous hits, the trees in Figure 1 were generated, indicating the orthologous tar or tag genes in those S. aureus strains. tarB, tarF, tarL, tarK from B. subtilis W23 and tagB, tagF from B. subtilis 168 share common BLAST hits in these S. aureus strains. We grouped these genes as well as their BLAST hits together to perform the phylogenetic analysis and built an integral tree (Figure 1e) to show their respective orthologous relationship.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis to identify Tar/Tag orthologs in S. aureus. The phylogenetic tree shows the orthologs of B. subtilis Tar/Tag ORFs in S. aureus strains Mu50, MW2, N315, MRSA252, MSSA476 and COL. BLAST hits (statistically significant) were used as input. MEGA3 program was used to perform this analysis. NJ trees were constructed using PC (Poisson Correlation) distance and a bootstrap value of 500. After deleting distant branches (homologs but not orthologs), final tree generated. Figure 1a depicts Tar/TagA orthologs. Figure 1b depicts Tar/TagD orthologs. Figure 1c depicts double TarI orthologs in each S. aureus strain. Figure 1d depicts double TarJ orthologs in each S. aureus strain. Figure 1e depicts orthologs of Tar/TagB, Tar/TagF, TarL and once again, two orthologs of TarL in each S. aureus strain are found. However, there is no ortholog of TarK.

Interestingly, these S. aureus orthologs, identified by phylogenetic analysis, shown in Figure 1, are actually the best BLAST hits (not shown). (We subsequently performed a "reverse BLAST hit" analysis on the identified S. aureus ORFs.) We took the S. aureus ORFs (the best BLAST hits) and BLASTed them back against B. subtilis strain 168 ORFs. Their corresponding tag genes were also identified as the best BLAST hits (not shown). The reverse BLAST was not performed for W23 strain since its genome sequence is not currently available. The reverse best BLAST hit analysis was in agreement with phylogenetic clustering in identifying the orthologous genes involved in wall teichoic acid synthesis in examined S. aureus strains (Figure 1). The orthologous relationship is also summarized in Table 1. We further performed dot-blot analysis, which also support the identified corresponding orthologous relationships (Figure 2a, 2b).

Table 1.

The BLAST homology between tar/tag genes and their orthologs in S. aureus strains. Newly identified TarB (named new_tarB) is also included. Orthologs of tagA/tarA are merged together. Same for tagD/tarD, tarF/tagF, tarB/tagB. Detail Blast Results are shown in Additional File 2 and annotations of these genes are shown in Additional file 3.

| N315 | Mu50 | MW2 | COL | MSSA476 | MRSA252 | |

| tagA | gi|15926313 | gi|15923626 | gi|21282327 | gi|57651477 | gi|49485508 | gi|49482864 |

| tarA | ||||||

| tagD | gi|15926318 | gi|15923631 | gi|21282332 | gi|57651482 | gi|49485513 | gi|49482869 |

| tarD | ||||||

| tagF | gi|5925967 | gi|15923244 | gi|21281959 | gi|57652514 | gi|49485134 | gi|49482490 |

| tarF | ||||||

| tagB | New_tarB | New_tarB | gi|21282330 | gi|57651480 | gi|49485511 | gi|49482867 |

| tarB | *gi|15926316 | *gi| 15926329 | ||||

| tarI | gi|15925958 | gi|15923245 | gi|21281960 | gi|57652515 | gi|49485135 | gi|49482491 |

| gi|15925954 | gi|15923241 | gi|21281956 | gi|57652511 | gi|49485129 | gi|49482485 | |

| tarJ | gi|15925959 | gi|15923246 | gi|21281961 | gi|57652516 | gi|49485136 | gi| 49482942 |

| gi|19525955 | gi|15923242 | gi|21281957 | gi|57652512 | gi|49485130 | gi|49482486 | |

| tarL | gi|15925956 | gi|15923243 | gi|21281958 | gi|57652513 | gi|49485131 | gi| 49482487 |

| gi|15925960 | gi|15923247 | gi|21281962 | gi|57652517 | gi|49485137 | gi|49482493 | |

| tarK |

*ORFs which the extension (new_tarB) are based.

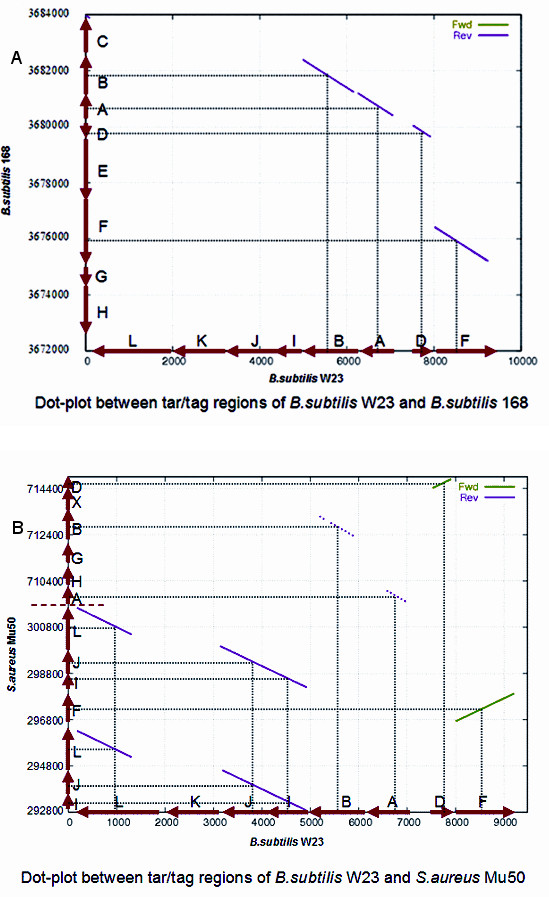

Figure 2.

Dot-blot analysis of tar/tag regions. Homologous relationships are confirmed by dot-blot analyis. Figure 2a shows the synteny and the homologous genes in the W23 tar and 168 tag regions. Figure 2b shows the synteny and the orthologous relationships of genes involved teichoic acid synthesis in B. subtilis W23 and Mu50. In Mu50, the tar genes are not clustered together. We artificially brought them together to make the dot-plot easy to read. Strains MW2, N315, MRSA252, MSSA476 and COL are the same as Mu50 (not shown).

S. aureus contains tarF instead of tagF

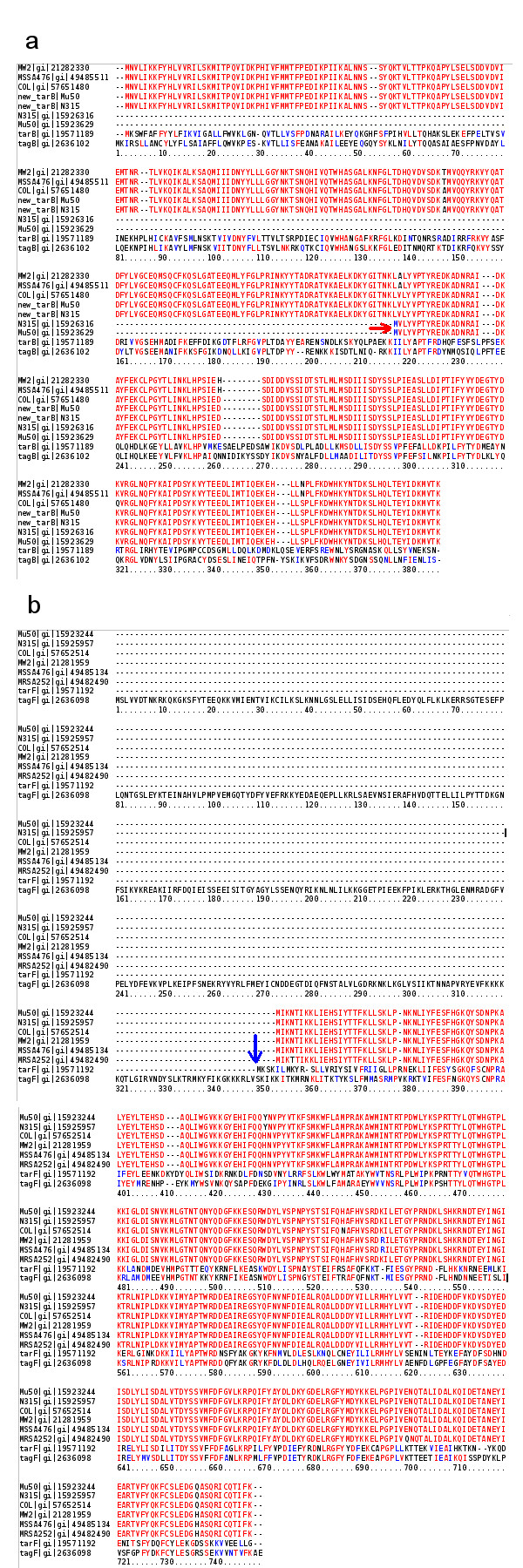

The protein alignment of S. aureus tagF/tarF orthologs with B. subtilis TagF and TarF (Figure 3b) shows that tagF/tarF orthologs in these S. aureus strains are fully aligned with the W23 TarF in length, and also like W23 TarF, are about only half the size of 168 TagF. And only the C-terminal part of the larger TagF is significantly homologous to TarF[2].

Figure 3.

Multiple sequence alignment of TarB/TagB, TarF/TagF (protein) and their orthologs. Figure 3a. TarB/TagB orthologous ORFs in Mu50 and N315 (Mu50|gi|15923269 and N315|gi|1592316) are much shorter than in other strains (red arrow), which is suspected as an annotation error. So ORF finder program was rerun on this region and new_tarBs in Mu50 and N315 were identified. As shown in figure, new_tarB|Mu50 is a upstream extension of Mu50|gi|15923269. new_tarB|N315 is a upstream extension of N315|gi|1592316. See Additional file 1 for sequences of new_tarBs. Figure 3b. The size and homology clear shows that the analyzed S. aureus strains contain TarF like protein rather than TagF (blue arrow).

In B. subtilis, despite sharing 60% identity, the size difference between TarF and TagF implies a functional difference. TagF and TarF both use CDP-glycerol as a substrate but do not carry out identical functions. In strain W23, TarF is likely to be responsible for the addition of the second glycerol-phosphate which completes the linkage unit process. While in 168, TagF polymerizes the complete glycerol-phosphate chain onto the first residue [6], which requires a bigger protein. Thus the size difference correlates with their functional difference between TagF and TarF. The size difference between TagF and TarF may also be used to differentiate tar or tag pathway in teichoic acid synthesis [5].

In the analyzed S. aureus strains, the size of tagF/tarF orthologs suggests the existence of TarF like function rather than TagF like function, and additional enzymes are required to complete teichoic acid synthesis[2].

S. aureus utilize tar pathway instead of tag pathway for teichoic acid biosynthesis

In B. subtilis strain W23, tarI, tarJ. tarK and tarL are specific to tar pathway, which are responsible for the synthesis of RboP and the addition of poly(RboP) to the linkage unit [2] and are absent in strain 168's tag pathway. The identification of tarI, tarJ and tarL orthologs (Figure 1 and Table 1) and the tarF kind of function (instead of that of tagF) strongly suggest that the tar rather than the tag pathway is employed for cell wall teichoic acid synthesis in analyzed S. aureus strains. In the rest of the paper, these S. aureus wall teichoic acid synthesis genes are all referred as tar genes (Tar prefix will be used to refer to their protein products).

There are two copies for each tar J, tarI and tarL gene in those S. aureus strains (Figure 1, Table 1 and Figure 2). Interestingly, the tarK ortholog is missing from the analyzed S. aureus strains. In W23, tarK and tarL are identified to catalyze a similar function, but tarL could take a bigger substrate enzymatically (poly(Rbop)) [6]. Thus the absence of tarK ortholog in S. aureus could either mean it is functionally replaced by one of the two tarL or be compensated for by the extra copy of tarL.

Identifying the correct full length tarB in S. aureus Mu50 and N315

According to multiple sequence alignment analysis and BLAST analysis of B. subtilis TarB/TagB (protein) with the corresponding S. aureus orthologs, the TarB ORFs in Mu50 and N315 were found to be notably shorter than B. subtilis TarB/TagB. They were also shown to lack half of the amino acid residues from the N-terminal of B.subtilis TarB/TagB (Figure 3a). One would expect that the translation start site would be further upstream in both strains. The ORF prediction was thus rerun on this genomic region (see methods), and the correct tarB/tagB in Mu50 and N315 were identified (see Additional file 1). The correct tarB in N315 is from 687949 to 689052, producing an ORF of 367 amino acids; the correct tarB In Mu50 is located between 712200 and 713303, also encoding an ORF of 367 amino acids. Both two new TarB ORFs were subsequently confirmed by a TBLASTN analysis against these two genomes with B. subtilis TarB as query. The new TarB ORFs in Mu50 and N315 strains and their alignment with the original incorrectly predicted ones are shown in Figure 3a.

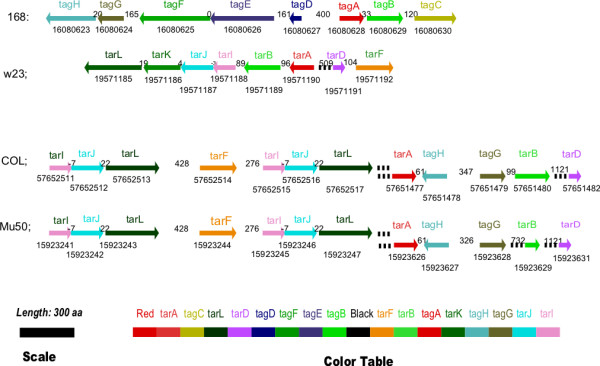

Genomic organization of tar genes and duplication of tarI, tarJ and tarL in S. aureus strains

In B. subtilis, the wall teichoic acid synthesis genes are organized into a divergon, tarABIJKL-tarDF in W23 and tagAB-tagDEF in 168 (Figure 4, Additional file 4). However, in S. aureus, the tar genes seem are rather organized by genomic distance as tarIJL-tarF-tarIJL-tarA-tarB-tarD in cis orientation (Figure 4, see Additional file 4). This genomic organization is conserved in all six analyzed S. aureus strains.

Figure 4.

Genomic organization of tar genes in S. aureus. Genomic organization of tar/tag genes W23, 168, S. aureus strains COL, Mu50 are shown here. The other 4 strains are not shown here since they have similar genomic organization (See Additional file 4 for complete figure). The top line of this figure shows the divergon organizations of B. subtilis W23 and 168 as a reference. The following two lines represented in arrows are graphic demonstration of genomic organization of the selected two S. aureus strains. Arrows in different colours represent different genes as illustrated by the colour table at the bottom. The length of each arrow is defined accurately by the scale, demonstrating the exact amino acid length of each gene. All six S. aureus strains share a similar genomic organization, which is quite different from B. subtilis W23 and 168 counterparts. GenBank gi numbers are indicated.

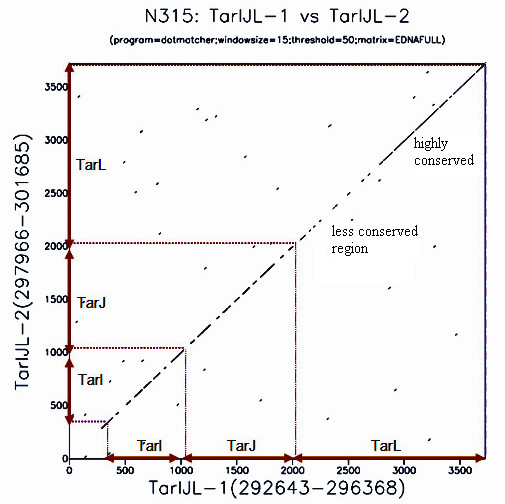

As shown above, BLASTP and phylogenetic analysis identify two copies of tarI, tarJ and tarL in each analyzed S. aureus strain, which are clustered into two tarIJL regions with the same gene order. Alignment and dot blot analysis of these two tarIJL regions in each S. aureus strain confirm this gene duplication (Figure 5, N315 is shown. The others with similar results are not shown). The relevant genomic sequences of tarIJL regions including the intergenic regions among I, J, K genes and the upstream 275 bp were used as an input for Dotmatcher program to perform dot-blot analysis of the two tarIJL regions (see Materials and Methods). We also ran the NCBI BLAST2seq program to align the two regions (not shown). These analyses further confirmed the homology between those two tarIJL regions, which strongly suggests the whole tarIJL region is duplicated. The high homology indicates the duplication should not be an evolutionary (or biologically) distal event. Why and how this gene duplication occurred is still a question that remains to be answered.

Figure 5.

Dot-blot analysis of the duplication of tarIJL in S. aureus N315. The two tarIJL regions in Mu50 were aligned and dot-plot analysis was performed. The homology between these two regions is clearly shown. The high homology also indicates this duplication should not be a remote event. And part of tarL region is less conserved, which indicate that two tarL copies could have different functions. This phenomenon can be used to explain why there is no homologs of tarK in these S. aureus strains. Other S. aureus strains give similar results and are not shown here.

The dot blot analysis also demonstrated that a small section of the C-terminal of tarJ is not very conserved in the two copies of tarJ. The enzymatic implication of this is not yet clear. Similarly, the N-terminal of tarL (almost half the size of tarL) is neither homologous between the two tarL genes. It implies that one of the tarL is very likely to be the missing tarK.

Discussion

To understand the biosynthesis of cell wall teichoic acid in S. aureus strains Mu50, MW2, N315, MRSA252, MSSA476 and COL, we took a bioinformatics approach to perform a comparative genomics analysis., We used the B. subtilis teichoic acid synthesis pathway as the base for comparison and identified all the genes essential to teichoic acid synthesis in these six S. aureus strains. Besides tarA/tagA, tarB/tagB, and tarD/tagD like genes, we identified tarF rather than tagF like gene and tar specific genes tarI, tarJ and tarL. The latter three ones are duplicated in these S. aureus strains.

In B. subtilis, tarA, tarB, tarD and tarF in W23 are the most similar to their counterparts in strain 168: tagA, tagB, tagD and tagF [6], whose functions in wall techoic acid synthesis are well understood [1,2]. Since tarF does not carry out a polymerization function as tagF does, W23 tar pathways requires tarI, tarJ, tarK and tarL to add poly(RboP) to the linkage unit to complete teichoic acid synthesis [2]. The identification of tarF like function and tarI, tarJ, tarL like genes strongly support the fact that the analyzed S. aureus strains use a tar like pathway and poly(RboP) is their major cell wall teichoic acids. This conclusion is consistent with the observations that a TarD rather than TagD like catalytic mechanism presentin S. aureus [13] and the identification of ribitol teichioc acid in the cell wall of S. aureus H [7,8].

The tarI, tarJ and tarL in the six analyzed S. aureus strains are duplicated. Compared to the W23 tar pathway, tarK is absent in the six S. aureus strains. Based on the proposed function of tarK and tarL [2], we suggest that tarK is functionally redundant with one of the tarL in S. aureus or compensated by the duplication of tarL. Figure 6 schematically describes the tar pathway in the analyzed S. aureus strains. Compared to the proposed tar pathway in B. subtilis W23 (Figure 6, top panel) [1], the TarK in W23 could be replaced by one of the S. aureus TarL, or the TarK and TarL steps in W23 are actually merged as one TarL step in S. aureus (Figure 6, bottom blocks). Table 2 lists the putative enzymatic functions for S. aureus tar genes based on the SWISSPROT annotation of B. subtilis W23 tar genes. In this report, we also identified the correct ORFs for tarB in S. aureus strains N315 and Mu50, which are actually longer than the original ORFs in GenBank.

Figure 6.

The tar pathway in S. aureus. The top panel is the tar pathway in B. subtilis W23 [1], In S. aureus The TarK in B. subtilis is either replaced by TarL or merged with TarL as a one step (bottom blocks).

Table 2.

Putative enzymatic functions of S. aureus Tar proteins

| Gene | SwissProt |

| TarA |

N-acetylglucosaminyldiphosphoundecaprenol N-acetyl-beta-D- mannosaminyltransferase. http://www.expasy.org/uniprot/TARA_BACSUhttp://www.expasy.org/enzyme/2.4.1.187 |

| TarB |

Putative CDP-glycerol:glycerophosphate glycerophosphotransferase tarB http://www.expasy.org/uniprot/TARB_BACSU |

| TarD |

Putative Glycerol-3-phosphate cytidylyltransferase. http://www.expasy.org/uniprot/TARD_BACSUhttp://www.expasy.org/enzyme/2.7.7.39 |

| TarF |

Putative CDP-glycerol:glycerophosphate glycerophosphotransferase tarF http://www.expasy.org/uniprot/TARF_BACSU |

| TarI |

Putative D-ribitol-5-phosphate cytidylyltransferase. http://www.expasy.org/uniprot/TARI_BACSUhttp://www.expasy.org/enzyme/2.7.7.40 |

| TarJ |

Putative ribitol-5-phosphate dehydrogenase http://www.expasy.org/uniprot/TARJ_BACSUhttp://www.expasy.org/enzyme/1.1.1.137 |

| TarK |

Putative ribitolphosphotransferase http://www.expasy.org/uniprot/TARK_BACSU |

| TarL |

Putative CDP-ribitol ribitolphosphotransferase http://www.expasy.org/uniprot/TARL_BACSUhttp://www.expasy.org/enzyme/2.7.8.14 |

The genomic organizations of tar genes in S. aureus are quite different from B. subtilis. They are organized into several clusters in cis rather than the divergon in B. subtilis, and may be subjected to different regulatory mechanisms.

Conclusion

As we analyzed, tar (teichoic acid ribitol) is the main teichoic acid biogenesis pathway in the S. aureus strains. And, the tar genes are organized into several genomic groups in cis and the genes specific to tar (relative to tag): tarI, tarJ, tarL are duplicated. The genomic organization of the S. aureus tar pathway suggests their regulations are different when compared to B. subtilis tar or tag pathway, which are grouped in two operons in a divergon structure.

Methods

Data sources

Six bacteria strains are included in this analysis: Staphylococcus aureus Mu50, MW2, N315, MRSA252, MSSA476, COL and Bacillus subtilis 168. Their respective Refseq proteomes are downloaded from NCBI microbial genomes website [15]. The complete geonome sequence of Bacillus subtilis W23 is not available yet. The Tar proteins in W23 (A, B, D, F, I, J, K, L) are also downloaded from NCBI microbial genomes website [15].

BLASTP search

The eight Tar proteins and five Tag proteins (A, B, D, E, F) were used as queries to BLASTP against the proteomes (ORFs) of S. aureus Mu50, MW2, N315, MRSA252, MSSA476 and COL. For each querying protein, using E value cut off of 1e-10, we collected all the significant hits.

To define the identified possible Tar/Tag homoglous proteins in six S. aureus strains, we also took the above identified S. aureus proteins (ORFs) to BLAST back against proteome of B. subtilis168. Mutual best BLAST hit is another evidence of the orthologous relationship.

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building

The above selected BLAST hits from the combined dataset plus the relevant Tar protein are taken to do ClustalW alignment. The multiple sequence alignment result is further taken as input to do phylogenetic analysis.

Mega3 package is used for phylogenetic analysis and tree building. First the ClustalW produced .aln files were transformed into Mega readable .meg files, followed by performing neighbour-joining phylogenetic analysis taking .meg files as inputs. The default Mega parameters were used when making NJ trees and performing bootstrap test (bootstrap replication time at 500).

Since Tar/TagB, Tar/TagF, TarL, and TarK share certain significant BLAST hits, we put them and their BLAST hits together to do ClustalW alignment and Mega analysis.

MUMmer alignment and dot plot analysis

MUMmer package V3.0 was downloaded from TIGR ftp sites [16], which was used to align between the B. subtilis 168 genome and each genome of the six S. aureus strains. Promer program was selected for its relatively high sensitivity. Promer generates amino acid alignments between two DNA input files which contain multiple sequences in FASTA format. Mummerplot was used to produce the dot-blot of the MUMmer alignments (Figure 2).

Identification of full length tarB in S. aureus Mu50 and N315

The TarB orthologs identified from S. aureus Mu50 and N315 Refseq proteomes are remarkably shorter than TarB in B. subtilis W23, MRSA252, MSSA476 and COL, missing the N-terminal part and only about half the size of W23 TarB. We applied NCBI's ORF finder program [14] to analyze the TarB regions of N315 and Mu50. Two extended ORFs were identified which were similar to W23 TarB in length. Alignment analysis confirmed they are TarB orthologs in these two S. aureus strains (Figure 3).

The ORF in N315 for TarB locates in the genome from 687949 to 689052, and ORF in Mu50 for TarB from 712200 to 713303.

The genomic organization of tar genes

The genomic localization information of Tar and Tag genes in B. subtilis 168, W23 and S. aureus strains Mu50, MW2, N315, MRSA252, MSSA476, COL were retrieved from NCBI microbial genomes website [15]. Genomic organization maps of the five bacteria were then made (Figure 4, Additional file 4).

Analysis of tarIJL duplication in S. aureus strains

BLASTP and phylogenetic analysis identified two copies of TarI, J and L in S. aureus Mu50, N315, MW2, MRSA252, MSSA476 and COL. From genomic analysis, TarI, TarJ and TarL in the analyzed S. aureus strains, are clustered into two tarIJL regions. To confirm that it is caused by gene duplication, we further performed alignment and dot-blot analysis of those two tarIJL regions in each of the S. aureus strains. [14]

We first cut out the relevant genomic sequences of tarIJL regions, including the intergenic regions among I, J, K genes and upstream 275 bp. Then we used dotmatcher program from EMBOSS package[17] to perform dot-blot analysis of the two tarIJL regions (Figure 5). We also ran NCBI bl2seq program to align the two regions (not shown).

Authors' contributions

ZQ, YY and YZ did most of the analysis. LL helped with organizing the data. YJ identified the miss annotation of S. aureus tar genes in GenBank and proposed the analysis. YL and YJ supervised the analysis and interpreted the results. ZQ, LL and YJ read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

new TarB sequences.fasta. New TarB sequences identified by NCBI ORFinder

The tar and tag orthologs in S. aureus. Identity and E-value are shown here. Newly identified TarB (named new_tarB) is also included. * Orthologs identified by dual-BLAST. ** Orthologs identified by Phylogenetic analysis (detail in figure 1). *** ORFs which the extension (new_tarB) are based.

Annotations of tar/tag orthologs in NCBI. NCBI annotations for tar/tag orthologs are shown here. Because of high homologous, tarA/tagA/tarB/tagB have been already annotated as teichoic acid biosynthesis protein, while other ORFs have not been well annotated.

full size genomic organization image. The top line of this figure is the divergon organization of tar and tag in B. subtilis W23 and 168 as a reference. The following six lines represented in arrows are graphic demonstration of genomic organization of the six S. aureus strains. Arrows in different colours represent different genes as illustrated by the colour table at the bottom. The length of each arrow is defined accurately by the scale, demonstrating the exact amino acid length of each gene. Figures below the arrows denote the GI numbers of corresponding gene. Figures between the arrows denote gap sizes in nucleotide unit between adjacent genes. Noting that, the black dots between some arrows denote the distances of corresponding genes, which are too long to illustrate by the normal scale. BLAST hits are also shown for each gene below. All six S. aureus strains share a similar genomic organization, which is quite different from their B. subtilis W23 and 168 counterparts.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dave Figuora at Merck Research laboratories for English editing and discussion. We also wish to thank Dr. Qing Zhang at Schering Plough Research Institute for suggestions. This study was supported by Major Program of Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology (No. 04dz14004) and National 973 Key Research Program of China (No. 2001CB510209, 2002CB713807, 2003CB715900).

Contributor Information

Ziliang Qian, Email: zlqian@sibs.ac.cn.

Yanbin Yin, Email: yinyb@mail.cbi.pku.edu.cn.

Yong Zhang, Email: zhangy@mail.cbi.pku.edu.cn.

Lingyi Lu, Email: lylu@sibs.ac.cn.

Yixue Li, Email: yxli@sibs.ac.cn.

Ying Jiang, Email: ying_jiang@merck.com.

References

- Pooley HM, Abellan FX, Karamata D. A conditional lethal mutant of Bacillus subtilis 168 with a thermosensitive glycerol-3-phosphate cytidylyltransferase, an enzyme specific for the synthesis of the major wall teichoic acid. J Gen Microbiology. 1991;137:921–928. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-4-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarevic V, Abellan FX, Moller SB, Karamata D, Mauel C. Comparison of ribitol and glycerol teichoic acid genes in Bacillus subtilis W23 and 168: identical function, similar divergent organization, but different regulation. Microbiology. 2002;148:815–824. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-3-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley J, Archibald AR, Baddiley J. A linkage unit joining peptidoglycan to teichoic acid in Staphylococcus aureus H. FEBS Lett. 1976;61:240–242. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)81047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauel C, Young M, Karamata D. Genes concerned with synthesis of poly(glycerol phosphate), the essential teichoic acid in Bacillus subtilis strain 168, are organized in two divergent transcription units. J Gen Micorbiol. 1991;137:929–941. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-4-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauel C, Bauduret A, Chervet C, Beggah S, Karamata D. In Bacillus subtilis 168, teichoic acid of the cross-wall may be different from that of the cylinder: a hypothesis based on transcription analysis of tag genes. Microbiology. 1995;141:2379–2389. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-10-2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pooley HM, Abellan FX, Karamata D. CDP-glycerol:poly(glycerophosphate) glycerophosphotransferase, which is involved in the synthesis of the major wall teichoic acid in Bacillus subtilis 168, is encoded by tagF (rodC) J Bacteriol. 1992;174:646–649. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.646-649.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley J, Tarelli E, Archibald AR, Baddiley J. The linkage between teichoic acid and peptidoglycan in bacterial cell walls. FEBS Lett. 1978;88:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80594-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima N, Araki Y, Ito E. Structure of linkage region between ribitol teichoic acid and peptidoglycan in cell walls of Staphylococcus aureus H. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:9043–9045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T, Takeuchi F, Kuroda M, Yuzawa H, Aoki K, Oguchi A, Nagai Y, Iwama N, Asano K, Naimi T, Kuroda H, Cui L, Yamamoto K, Hiramatsu K. G enome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet. 2002:1819–1827. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden MT, Feil EJ, Lindsay JA, Peacock SJ, Day NP, Enright MC, Foster TJ, Moore CE, Hurst L, Atkin R, Barron A, Bason N, Bentley SD, Chillingworth C, Chillingworth T, Churcher C, Clark L, Corton C, Cronin A, Doggett J, Dowd L, Feltwell T, Hance Z, Harris B, Hauser H, Holroyd S, Jagels K, James KD, Lennard N, Line A, Mayes R, Moule S, Mungall K, Ormond D, Quail MA, Rabbinowitsch E, Rutherford K, Sanders M, Sharp S, Simmonds M, Stevens K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG, Spratt BG, Parkhill J. Complete genomes of two clinical Staphylococcus aureus strains: evidence for the rapid evolution of virulence and drug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:9786–9791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402521101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda M, Ohta T, Uchiyama I, Baba T, Yuzawa H, Kobayashi I, Cui L, Oguchi A, Aoki K, Nagai Y, Lian J, Ito T, Kanamori M, Matsumaru H, Maruyama A, Murakami H, Hosoyama A, Mizutani-Ui Y, Takahashi NK, Sawano T, Inoue R, Kaito C, Sekimizu K, Hirakawa H, Kuhara S, Goto S, Yabuzaki J, Kanehisa M, Yamashita A, Oshima K, Furuya K, Yoshino C, Shiba T, Hattori M, Ogasawara N, Hayashi H, Hiramatsu K. Whole genome sequencing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2001;357:1225–1240. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SR, Fouts DE, Archer GL, Mongodin EF, Deboy RT, Ravel J, Paulsen IT, Kolonay JF, Brinkac L, Beanan M, Dodson RJ, Daugherty SC, Madupu R, Angiuoli SV, Durkin AS, Haft DH, Vamathevan J, Khouri H, Utterback T, Lee C, Dimitrov G, Jiang L, Qin H, Weidman J, Tran K, Kang K, Hance IR, Nelson KE, Fraser CM. Insights on evolution of virulence and resistance from the complete genome analysis of an early methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain and a biofilm-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis strain. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:2426–2438. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2426-2438.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badurina DS, Zolli-Juran M, Brown ED. CTP:glycerol 3-phosphate cytidylyltransferase (TarD) from Staphylococcus aureus catalyzes the cytidylyl transfer via an ordered Bi-Bi reaction mechanism with micromolar K(m) values. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003:196–206. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(03)00019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCBI's ORF finder program http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html

- NCBI microbial genomes website http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/MICROBES/Complete.html

- TIGR ftp site ftp://ftp.tigr.org/pub/software/MUMmer/

- EMBOSS package http://emboss.sourceforge.net/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

new TarB sequences.fasta. New TarB sequences identified by NCBI ORFinder

The tar and tag orthologs in S. aureus. Identity and E-value are shown here. Newly identified TarB (named new_tarB) is also included. * Orthologs identified by dual-BLAST. ** Orthologs identified by Phylogenetic analysis (detail in figure 1). *** ORFs which the extension (new_tarB) are based.

Annotations of tar/tag orthologs in NCBI. NCBI annotations for tar/tag orthologs are shown here. Because of high homologous, tarA/tagA/tarB/tagB have been already annotated as teichoic acid biosynthesis protein, while other ORFs have not been well annotated.

full size genomic organization image. The top line of this figure is the divergon organization of tar and tag in B. subtilis W23 and 168 as a reference. The following six lines represented in arrows are graphic demonstration of genomic organization of the six S. aureus strains. Arrows in different colours represent different genes as illustrated by the colour table at the bottom. The length of each arrow is defined accurately by the scale, demonstrating the exact amino acid length of each gene. Figures below the arrows denote the GI numbers of corresponding gene. Figures between the arrows denote gap sizes in nucleotide unit between adjacent genes. Noting that, the black dots between some arrows denote the distances of corresponding genes, which are too long to illustrate by the normal scale. BLAST hits are also shown for each gene below. All six S. aureus strains share a similar genomic organization, which is quite different from their B. subtilis W23 and 168 counterparts.