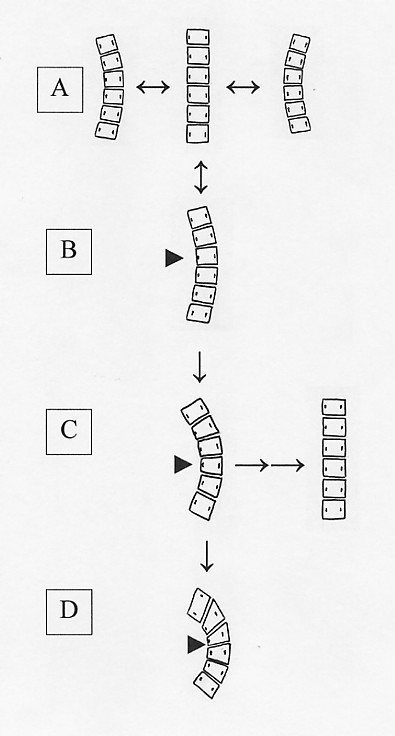

Figure 1.

Evolution of a structural deformity of the spine. A. Normal dynamics of spinal movement. A normal human spine is programmed to assume a wide range of positions, including curvatures to the left or right ('scoliosis'), in response to stimuli. Such curvatures are transient and reversible and occur numerous times during the course of a day. B. Functional curvature. Radiographs of an individual with an asymmetric posture commonly reveal a spinal curvature which resolves when the patient adjusts his posture. Any curvature which reverts to a straight spine when the person bends to the side or lies down is considered to be a functional curvature, not a spinal deformity. As in a normal spine, the curvature, rotation of vertebrae, and associated torso imbalance are flexible and reversible, and there is no deformation of vertebral bodies (triangle). In some cases, such as a trauma-induced scoliosis due to a car wreck, the functional curvature may last for a few days and then resolve when the injuries heal and the pain resolves. In other cases, such as a pain-induced curvature in which the injury is never treated appropriately, the functional curvature may become habitual and linger indefinitely. In older children, once a curvature has been present for more than a year it usually will not resolve even if the inciting problem does resolve [19,29]. Eventually, a state of continuous asymmetric loading is established and maintained sufficiently to reach a threshold required to affect growth plates within the spinal bones. C. Structural curvature: Before skeletal maturity. Ultimately, under the constant stress of asymmetric loading, there is a predictable change in skeletal architecture (triangle), and the curvature evolves into a spinal deformity which no longer is flexible and readily reversible. Once this occurs, there is a fixed asymmetric deformity of the torso that does not resolve when the patient adjusts his posture. Once the curvature has progressed into a structural deformity, it still can be mild, nondeforming, and of little threat to the person's health and well-being. However, the vicious cycle model predicts that the continuous asymmetric load, however small, will push it in the direction of progression unless steps are taken to counteract it. The more asymmetric the load, the likelier it is that the curvature will progress. Yet, even with severe structural deformities the curvature can be reversed if the state of continuous loading is reversed and symmetrical pressure on the growth plates is restored (right). D. Structural curvature: After skeletal maturity. Once bone growth is complete, vertebral deformities persist for life. However, despite the structural deformity at the apex of the curvature, other parts of the spine remain flexible and can still correct on side bending [33,78,80–82]. Thus, a curvature measuring 50 degrees in the standing position may correct to 30 degrees in the supine position. This 20-degree 'functional' component of the curvature can still be corrected by a change in posture, but the overall flexibility of the spine decreases with age [78,79]. Progression of the curvature results from continued asymmetric loading of the deformed vertebral elements, at an average rate of 10 degrees per decade, with a corresponding loss in height of 1.5 cm per decade beginning in early adulthoold [83].