Abstract

Lymphatic filariasis is a tropical disease caused by the nematode parasites Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi. Whereas the protective potential of T lymphocytes in filarial infection is well documented, investigation of the role of B lymphocytes in antifilarial immunity has been neglected. In this communication, we examine the role of B lymphocytes in antifilarial immunity, using Brugia pahangi infections in the murine peritoneal cavity as a model. We find that B lymphocytes are required for clearance of primary and challenge infections with B. pahangi third-stage larvae (L3). We assessed the protective potential of peritoneal B lymphocytes by adoptive transfer experiments. Primed but not naïve peritoneal B cells from wild-type mice that had been immunized with B. pahangi L3 protected athymic recipients from challenge infection. We evaluated possible mechanisms by which B cells mediate protection. Comparisons of cytokine mRNA expression between B-lymphocyte-deficient and immunocompetent mice following B. pahangi infection suggest that B cells are required for the early production of Th2-type cytokines by peritoneal cells. In addition, B-cell-deficient mice demonstrate a defect in inflammatory cell recruitment to the peritoneal cavity following B. pahangi infection. The data demonstrate a critical role of B lymphocytes in antifilarial immunity in naïve mice and in the memory response in primed mice.

Lymphatic filariasis, a major public health problem in 80 tropical countries, affects 120 million people and is caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, which accounts for 90% of the infections, and Brugia malayi, which causes the remaining 10% (2). Both parasite species have complex life cycles which require vertebrate and mammalian hosts and, similar to other nematodes, must complete distinct developmental stages which are separated by molting events. Human infection is initiated when infective third-stage larvae (henceforth, L3) are deposited onto the skin of a human host by an infected mosquito during a blood meal. The L3 crawl subcutaneously through the bite wound and migrate to the lymphatics, where the parasites live through all the mammalian stages of the life cycle.

In the laboratory setting, murine infections with B. malayi or the closely related parasite Brugia pahangi have been used extensively over the past 10 years to study host-parasite interactions. Although the original studies of brugian infection in mice used the subcutaneous route of infection, it was later discovered that intraperitoneal (i.p.) infections with B. pahangi L3 allowed more accurate determinations of worm burdens (19). When injected i.p., the parasites develop normally and infection progresses to patency in permissive hosts with similar kinetics to mosquito-transmitted infection. Moreover, the parasites remain in the peritoneal cavity and can be easily recovered by peritoneal lavage (8). This method has been widely accepted for the study of filarial biology and host-parasite interactions.

Normal immunocompetent inbred C57BL/6 and BALB/cByJ mice are refractory to infection with brugian parasites. However, infection develops to patency in immunodeficient scid/scid or RAG-1−/− mice that lack an adaptive immune system (20). This suggests that mice can support the normal development of these organisms and that immunocompetent mice are able to actively clear the infection due to an efficient immune response. Studies using T-cell-deficient NUDE mice with B. malayi or B. pahangi demonstrated that these mice develop patent infection and harbor parasites as late as 240 days postinfection (28, 29, 31, 33, 34). Furthermore, the susceptibility of NUDE mice to B. pahangi infection was reversed by immune reconstitution with neonatal thymocytes from wild-type syngeneic mice or by implantation of neonatal thymus grafts several weeks prior to infection (32).

Our previous studies demonstrated a role for B lymphocytes in protection against Brugia infection and the potential of naïve peritoneal cells to transfer this protection to immunodeficient mice (22). In this communication we report the transfer of protection against B. pahangi to T-cell-deficient mice with primed purified peritoneal B lymphocytes and analyze possible mechanisms of B-cell-mediated protection against infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

All mice used in this study were young adult males. The mouse strains that were used are listed in Table 1. They were maintained in the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited vivarium of the University of Connecticut Health Center (UCHC) in microisolator chambers and permitted lab chow and sterile water ad libitum. For the colonies that were bred and maintained at the UCHC facility, random mice were regularly phenotyped to ensure genetic purity of the colony. All procedures on mice were performed after appropriate review by and clearance from the institutional Laboratory Animal Welfare Committee.

TABLE 1.

Mouse strains used

| Mouse straina | Abbreviation | Mutation | Known immunological defect |

|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6J | B6 | None | None |

| B6.129S2-Igh-6tm1Cgn | B6 Igh6−/− | Induced deletion of membrane exon of μ heavy chain | Block of B-cell maturation at pre-B cells |

| B6.Cg-Foxn1nu | B6 NUDE | Forkhead box N1 | No T lymphocytes |

| C57BL/6 JH−/− | B6 JHD | Induced deletion of JhD segment | Block of B-cell maturation at pre-B cells |

| B6.CB17-Prkdcscid/SzJ | B6 SCID | Natural mutation in Prkdc locus | No B or T cells |

| B6.129P2-Fcgr3tm1Sjv | B6 FcgRIII−/− | Induced mutation in Fcg3 | No FcRγ3 |

| B6.129P2-Fcerg1tm1 | B6 FcRg−/− | Induced mutation in Fcg1 | No FcRγ1, FcRγ3, and FcRε1 |

| B6.129S6 | B6 | None | None |

| C57BL/6 CD1−/− | B6 CD1−/− | Induced mutation at the CD1 locus | No CD1-mediated antigen presentation |

| CBA/CaJ | CBA/Ca | None | None |

| CBA/CaHN-Btkxid/J | CBA/N | Natural mutation at Btk locus | No B1 B cells; other defects as well |

| BALB/cByJ | BALB/c | None | None |

| BALB/c JHD | BALB/c JHD | Same as in C57BL/6 JH−/− | Same as in C57BL/6 JH−/− |

| BALB/c Tcrbnull | BALB/c TCR-β−/− | Induced mutation in TCR-β locus | No TCR-αβ T cells |

| CBySmn.CB17-Prkdcscid/J | BALB/c SCID | Same as in B6.CB17-Prkdcscid/SzJ | Same as in B6.CB17-Prkdcscid/SzJ |

| B6.129S6-Iitm1Liz | B6 Ii−/− | Induced mutation at the Ii locus | No MHC class II antigens or CD4 T cells |

All mice from the Jackson Laboratory came from the research colonies of L. D. Shultz, except C57BL/6 JH−/− were from William Weidanz, Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of Wisconsin Medical School, Madison, and BALB/c JHD were from Mark Shlomchik, Departments of Laboratory Medicine and Immunobiology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.

Infective larvae.

B. malayi or B. pahangi infective larvae were obtained either from the laboratory of Thomas Klei (Louisiana State University), TRS Inc., Athens, Ga., or the University of Georgia (Athens), through a contract with the National Institutes of Health (U.S.-Japan Collaborative Program in Filariasis). Infective larvae were shipped in Ham's complete medium as described previously (35). Upon arrival, the larvae were resuspended in fresh RPMI 1640 cell culture medium (GIBCO Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.), aliquoted, and counted prior to injection.

Infection and parasite recovery.

Mice were infected i.p. with 45 to 50 Brugia L3 in 400 μl of RPMI unless stated otherwise. For priming, mice were injected with 25 to 40 L3 i.p. Mice were euthanized in a CO2 chamber at various times following challenge infection. The peritoneal cavities were washed with RPMI, supplemented with 5 USP U of heparin (American Pharmaceutical Partners, Inc., Los Angeles, Calif.)/ml to recover viable L3, L4, or adult worms. In addition, the mice were soaked in Tris or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with their peritoneal cavities open, to allow the remaining worms to crawl out. Worm counts were performed under a dissecting microscope, and worm burdens were expressed as a percentage of the infecting dose (50 L3). Microfilariae were identified microscopically in the blood or in the peritoneal lavage.

Adoptive transfers of peritoneal cells.

For peritoneal exudate cell (PEC) transfers, peritoneal lavage was performed with 10 ml of ice-cold RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum and 5 USP U of heparin/ml. When donor mice had been previously infected with Brugia L3, the lavage fluid was assessed microscopically for the presence of the parasites and the larvae were removed manually prior to collection of cells. Cells were separated using MidiMACS positive selection columns (LS+) following the protocol provided by Miltenyi Biotec Inc. (Auburn, Calif.). Briefly, PECs were washed and resuspended in the labeling buffer (PBS, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 2 mM EDTA, pH 7.2) at a final concentration of 5 × 107 cells in 500 μl. Cells were labeled with biotinylated anti-mouse CD19 (clone 1D3; BD PharMingen) followed by incubation with streptavidin-coated microbeads (481-01; Miltenyi Biotec Inc.). Labeled cells were separated by passage through a magnetic separation column. Cells were injected i.p.

FACS analyses.

PECs were collected from animals individually and counted using a hemocytometer. Cell concentrations were adjusted to 107/ml in staining buffer (PBS, 0.2% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% NaN3). An aliquot containing 106 cells (100 μl) was incubated with 10 to 100 μl of appropriately diluted antibodies at 4°C. All antibodies were obtained from BD PharMingen, unless stated otherwise. After staining, cells were washed twice with staining buffer and fixed in 0.5% buffered formalin. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) data were acquired on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) and analyzed using WinMDI (Joseph Trotter, The Scripps Research Institute).

RNase protection assay.

RNA was isolated from pooled peritoneal cells using TRIzol (GIBCO Life Technologies). RNA concentration and purity were determined by measuring the optical density at 260 nm (OD260) and OD280. RNA solutions were aliquoted and stored at −70°C until use.

RNase protection assays were performed using the in vitro transcription and RiboQuant RNase protection assay kits (catalogue no. 45004K and 45014, respectively; PharMingen) using the protocol provided by the vendor. The mCK-1 (45001P) and mCK-5 (45026P) probes were used. [α-32P]UTP was bought from NEN Life Sciences (Boston, Mass.).

Statistical analysis.

The data are presented with standard deviation values. Two-tailed Student's t tests were used to compare control and experimental groups.

RESULTS

B-lymphocyte-deficient mice are permissive to primary and challenge infections with B. pahangi.

In our previous publications we reported that B6 Igh6−/− mice are significantly more permissive to Brugia infection than their immunocompetent counterparts (22). In order to ensure that the permissive phenotype of these mice is due to the absence of B lymphocytes rather than some other (uncharacterized) deficit in this particular strain, we analyzed B. pahangi infection in another B-cell-deficient strain, BALB/c JHD, and compared parasite recoveries from these mice with those from other mutants known to be permissive to B. pahangi infection. Figure 1 compares B. pahangi infection in wild-type, JHD, T-cell receptor-β-deficient (TCRβ−/−), and SCID mice on the BALB/c background. In this experiment BALB/c+/+ mice essentially clear the infection by 3 weeks postinfection, whereas BALB/c JHD mice have significantly higher worm burdens. At this time point, T-lymphocyte-deficient mice have significantly fewer worms than B-lymphocyte-deficient JHD or T- and B-lymphocyte-deficient SCID mice. At 12 weeks postinfection, parasite recoveries were not statistically different among the three immunodeficient strains, while all of them had significantly more parasites than wild-type mice. Interestingly, microfilariae were present in the peritoneal cavities of SCID and TCRβ−/− mice but none were observed in JHD mice, despite the presence of significant numbers of both male and female worms.

FIG. 1.

B. pahangi recoveries from BALB/c+/+, BALB/c TCRβ−/−, BALB/c JHD, and BALB/c SCID mice. BALB/c+/+, BALB/c TCRβ−/−, BALB/c JHD, and BALB/c SCID mice were infected with 50 B. pahangi L3. Worm recoveries were quantitated as described in the text. Each bar represents the average from five mice. Microfilariae were identified by microscopic analysis of the peritoneal lavage.

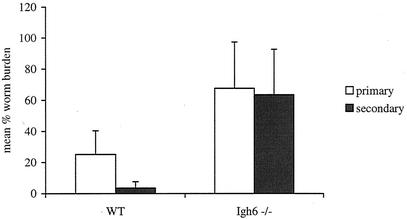

We recently reported that wild-type mice exhibit accelerated clearance of challenge infection following priming with live Brugia L3. We also reported that accelerated clearance of challenge infection does not happen in T-lymphocyte-deficient mice (25). We investigated the requirement for B lymphocytes in a challenge infection with B. pahangi parasites. Cohorts of wild-type or Igh6−/− mice on a B6 background were primed with 50 infective-stage larvae 2 months prior to challenge infection. Fourteen days after the challenge infections, worm recoveries were 25% in the primary infection and 3.5% in the challenge infection in the wild-type mice (P < 0.05). In contrast, in Igh6−/− mice parasite recoveries were virtually identical in the primary and secondary infection groups (68 and 64%, respectively) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Comparison between B. pahangi recoveries following primary or challenge infection in B6+/+ (WT) and B6 Igh6−/− mice. B6+/+ and B6 Igh6−/− mice were immunized with 50 B. pahangi L3 i.p. Two months following immunization, these groups and nonmanipulated control groups received a challenge infection with 50 B. pahangi L3. Worm recoveries were quantitated at 2 weeks postinfection. The bars represent the average from eight mice for all the groups except the Igh6−/− group that received only challenge infection, which had seven mice. P is <0.001 for wild-type mice.

Primed peritoneal B lymphocytes can transfer protection against B. pahangi infection to T-cell-deficient NUDE mice.

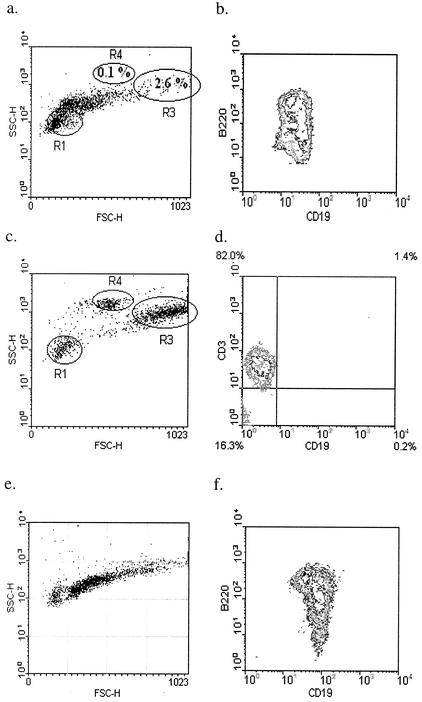

We investigated the ability of peritoneal B lymphocytes to transfer protection against B. pahangi infection to T-lymphocyte-deficient mice. It is well established that T cells are required for the successful elimination of brugian parasites from mice. We hypothesized that T cells are critical for the activation of the peritoneal B cells. We further hypothesized that once this activation occurred, peritoneal B lymphocytes could transfer protection to the T-cell-deficient NUDE mice, without the continued presence of T cells. We compared the ability of peritoneal B lymphocytes from either naïve or previously exposed mice to transfer protection. PECs were collected from either naïve or previously infected B6+/+ mice. B lymphocytes were purified by positive selection on magnetic bead separation columns by using an anti-CD19 antibody. Figure 3 shows the forward and side scatter profiles of the positively selected (Fig. 3a) and the flowthrough fractions (Fig. 3c). Macrophages (gate R3) and eosinophils (gate R4) are notably absent in the positively selected fraction, which only contains cells that stain positively for CD19 and B220 (Fig. 3b). In contrast, the flowthrough fraction has distinct macrophage and eosinophil populations. In addition, most of the lymphocytes in this fraction fall in the small lymphocyte gate (R1), and 80% stain positively with an anti-CD3 antibody (Fig. 3d).

FIG. 3.

Donor PECs used for reconstitution of B6 NUDE mice. (a to d) Twenty B6+/+ mice were immunized with 25 B. pahangi L3. PECs were collected at 3 weeks following immunization and B cells were purified. Panels a and b show the positively selected fraction. Gates R1, R3, and R4 in panel a demarcate small lymphocytes, macrophages, and eosinophils, respectively. Panels c and d show the B-cell-depleted flowthrough fraction. Panel d is gated on small lymphocytes (R1). Cells were stained with anti-CD19-FITC and B220-PE, and anti-CD3-PE. (e and f) PECs were collected from 35 naïve B6+/+ mice. B lymphocytes were purified using the same protocol and reagents as described for primed donor cells. Both panels show positively selected CD19+ peritoneal cells. Cells were stained with anti-CD19-FITC and B220-PE.

Positively selected cells were used to reconstitute B6 NUDE mice (5 × 106 cells per recipient). A control group of NUDE mice was reconstituted i.p. with positively selected CD19+ peritoneal cells from B6+/+ donors that had not been exposed to Brugia parasites (Fig. 3e and f).

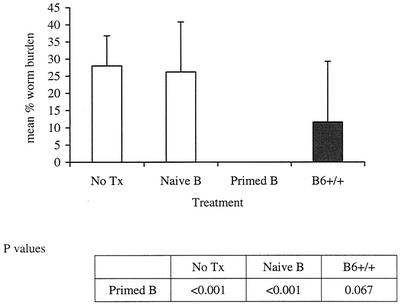

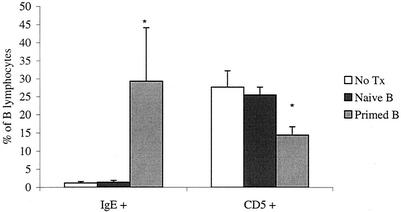

Reconstituted mice were infected with B. pahangi L3 9 days after cell transfer. Cohorts of nonmanipulated B6 NUDE mice and B6+/+ mice were infected, as well as additional control groups. All mice were necropsied 2 weeks postinfection. The mean worm burdens are shown in Fig. 4. All NUDE recipients of primed purified peritoneal B cells had no worms in the peritoneal cavity at the time of necropsy (average, 0%). In contrast, all wild-type mice had live parasites (12% average). Primed B lymphocytes not only facilitated worm clearance in NUDE recipients but also demonstrated the capacity to promote a degree of resistance to the parasites similar to that expected in primed wild-type mice. Remarkably, NUDE recipients of naïve peritoneal B cells had worm burdens that were comparable to those in nonmanipulated NUDE mice (26 and 28%, respectively). Phenotypic analysis of B lymphocytes showed that there was a significant increase in immunoglobulin E-positive (IgE+) cells and a significant decrease in CD5+ cells in the mice that received primed peritoneal B cells (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

B. pahangi recoveries from NUDE mice reconstituted with purified wild-type peritoneal B lymphocytes. B6 NUDE mice were reconstituted with 5 × 106 naïve or primed peritoneal B lymphocytes via i.p. injection. One week later, both reconstituted cohorts, a group of nonmanipulated B6 NUDE mice (No Tx), and a group of B6+/+ mice were infected with 50 B. pahangi L3 intraperitoneally. All mice were necropsied at 2 weeks postinfection and worm burdens were quantitated. n = 10 for the No Tx and primed B groups; n = 9 for the naïve B group; n = 5 for the B6+/+ group.

FIG. 5.

Proportions of IgE+ and CD5+ B lymphocytes in the peritoneal cavity of nude mice reconstituted with naïve or primed peritoneal B cells. PECs were gated on lymphocytes and analyzed using anti-IgE-FITC and anti-CD19-biotin or anti-CD19-FITC and anti-CD5-PE. Each bar represents the average from 10 (primed B and no treatment [No Tx] groups) or 9 (naïve B group) mice. The values from the primed B group for both cell types were significantly different from the other groups (P < 0.000).

Cell recruitment to the site of infection in B-lymphocyte-deficient mice.

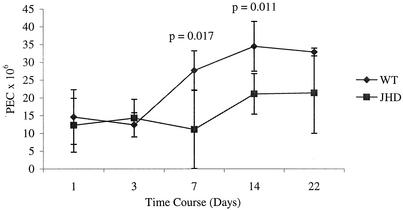

Since very little work has been done to address the role of B lymphocytes in filarial infection, there are no data to indicate the mechanisms of B-lymphocyte-mediated protection in this model. Our studies of the immune response to the parasites in wild-type mice indicated that, in a resistant host, parasite entry is followed by an increase in peritoneal cells. This observation suggested that cell recruitment to the site of infection is critical for parasite clearance. We compared cell accumulations in the peritoneal cavities of B6+/+ and B6 JHD mice following B. pahangi infection. Naïve B-cell-deficient and wild-type mice had equivalent PEC numbers. These numbers also did not diverge between these two strains at early time points of infection, but they did so by 1 week postinfection (Fig. 6). Wild-type mice more than double the cell numbers at the site of infection between days 3 and 7 postinfection, whereas the increase in JHD mice is apparent only at day 14 postinfection.

FIG. 6.

Comparisons of PEC accumulation following B. pahangi infection between B6+/+ (WT) and B6 JHD mice. Groups of 25 B6+/+ and 25 B6 JHD mice were infected with 50 B. pahangi L3. Cohorts of five mice from each group were necropsied at different time points postinfection. PECs were recovered and counted by using a hemocytometer.

Analysis of the PEC profiles of these two cohorts is shown in Table 2. Naïve B6 JHD mice had more T cells than wild-type mice (zero time point). However, by day 7 postinfection more T lymphocytes were present in wild-type mice compared to JHD mice. The difference became statistically significant by 2 weeks postinfection.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of different cell types in the peritoneal cavity following B. pahangi infection in B6+/+ versus B6 JHD micea

| Strain | No. of peritoneal T lymphocytes (106) at day postinfection:

|

No. of peritoneal eosinophils (106) at day postinfection:

|

No. of peritoneal macrophages (106) at day postinfection:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 14 | 22 | 7 | 14 | 22 | 7 | 14 | 22 | |

| B6+/+ | 0.3 ± 0.07 | 0.3 ± 0.04 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 9.4 ± 2.4 | 4.6 ± 1.9 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 12 ± 2.3 | 20 ± 4.7 | 19 ± 4.6 |

| B6 JHD | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.06 | 1.1 ± 1 | 0.5 ± 0.2∗b | 0.9 ± 0.3∗ | 0.5 ± 0.2∗ | 3.1 ± 5∗ | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± 1.8 | 7 ± 5.6 | 15 ± 4.5 | 16 ± 9.1 |

PECs were collected from B6+/+ or B6 JHD mice at various time points following B. pahangi infection and analyzed by flow cytometry. The zero time point represents the naïve mouse group. T cells were identified by staining with anti-CD3-FITC. Macrophages and eosinophils were measured by their forward and side scatter parameters.

∗, significantly lower than wild-type value (P ≤ 0.05).

Although there were fewer eosinophils in JHD mice at day 7 postinfection, their numbers were not different from those of wild-type mice at later time points (Table 2). Notably, the eosinophil numbers peak at 1 week postinfection in wild-type mice and then decrease. This peak coincides with the period of maximum worm clearance. Worm burdens in wild-type mice decrease from 50% recovery at day 7 to 1% recovery at day 14 postinfection. We have observed that, unlike macrophages, which are resident cells in the peritoneal cavity, eosinophils in the peritoneal cavity are specific for the presence of parasites, and their numbers decrease as soon as the infection is cleared. JHD mice have steady numbers of eosinophils at the site of infection at all time points measured. We observed no differences in macrophage numbers between the two groups at any time point measured (Table 2).

Role of B-cell-dependent cytokine production in the antifilarial immune response.

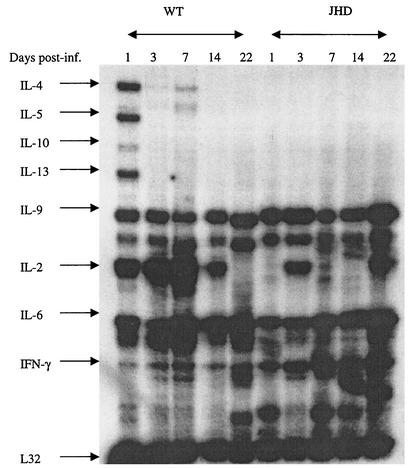

Recent reports have demonstrated cytokine production by B lymphocytes and their possible role in immunoregulation (11). In order to investigate how the absence of B lymphocytes might influence cytokine production in response to filarial parasites, we compared cytokine mRNA levels in the peritoneal cavities of wild-type and B-cell-deficient mice at various times postinfection. Figure 7 shows the data obtained from a total of 50 mice (25 each of B6+/+ and B6 JHD). Five mice of each strain were used for each time point.

FIG. 7.

Cytokine expression by PECs from B6+/+ (WT) and B6 JHD mice infected with B. pahangi. Groups of 25 B6+/+ mice and 25 B6 JHD mice were infected with 50 B. pahangi L3. Five mice from each cohort were sacrificed on days 1, 3, 7, 14, and 22 postinfection. PECs were collected from each group, pooled, and used for RNA preparation. Forty micrograms of RNA from each group was used for an RNase protection assay using the mCK-1 probe. Each lane shows cytokine expression from five mice.

Clear differences were observed between the two groups. Wild-type mice demonstrate a strong upregulation of steady state interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, and IL-13 mRNA levels as early as day 1 postinfection. These mRNA levels decrease thereafter. IL-10 is also measurable at this early time point. In contrast, these cytokine mRNAs are not detected in JHD mice. In addition, JHD mice exhibit higher steady-state message levels for gamma interferon than wild-type mice.

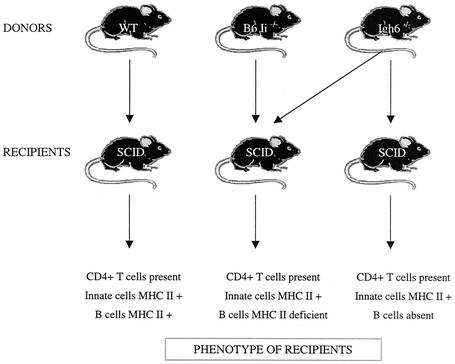

Antigen presentation by B lymphocytes is not required for protection against Brugia infection.

B lymphocytes express major histocompatibility class (MHC) class II surface antigens and can present antigens to CD4+ T cells. Moreover, Zimecki et al. showed that peritoneal B1 cells are more efficient antigen-presenting cells than conventional B cells or nonperitoneal B cells (36). We investigated the role of MHC class II-mediated antigen presentation by B cells in response to filarial parasites.

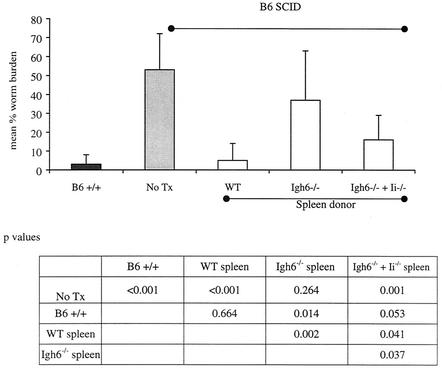

Mice that do not express MHC II antigens manifest an immunological defect in addition to the expected lack of MHC II antigens (6, 10). Due to failure of expression of MHC class II antigens, they also lack CD4+ T lymphocytes. A requirement for CD4+ T cells in the clearance of Brugia parasites is well established (4). Therefore, independent of MHC II expression, the lack of CD4+ T cells can render MHC class II-deficient mice permissive to Brugia parasites. In order to differentiate between the protective effect mediated by CD4+ T cells and the one that is mediated through MHC II presentation, we used the adoptive transfer protocol depicted in Fig. 8. B6 SCID recipients were reconstituted with spleen cells from B6+/+ mice or B6 Igh6−/− mice, or with an equal mixture of B6 Igh6−/− and B6 MHC II-deficient spleen cells (from B6.129S6-Iitm1Liz mice). SCID recipients of wild-type splenocytes are expected to have normal lymphocyte populations and MHC II expression, whereas the SCID mice reconstituted with Igh6−/− spleen cells would be phenotypically similar to Igh6−/− mice. The last group would contain B lymphocytes that do not express MHC II antigens but other cell types that would. Most importantly, the absence of MHC II expression on B cells in these mice would not be associated with an absence of CD4+ T cells. In addition, a cohort of nonmanipulated B6 SCID mice was included as a positive control. The results of this experiment are shown in Fig. 9. The SCID recipients of wild-type splenocytes had significantly lower worm burdens than either nonmanipulated SCID mice or the recipients of Igh6−/− spleen cells. The mice that received a mixture of Igh6−/− and MHC II-deficient splenocytes were also able to decrease worm burdens significantly compared to the two control groups. Therefore, the addition of MHC II-deficient B lymphocytes can restore protection against Brugia infection in mice, suggesting that MHC II-mediated antigen presentation by B cells may not be critically required for host protection.

FIG. 8.

Experimental design for the investigation of the requirement for the antigen-presenting function of B lymphocytes.

FIG. 9.

B. pahangi recoveries from B6 SCID mice reconstituted with different antigen-presenting cell types. Ten B6 SCID mice were reconstituted with 2 × 107 spleen cells from B6+/+ mice (WT), 10 B6 SCID mice received 107 spleen cells from B6 Igh6−/− mice, and 10 B6 SCID mice received an equal mixture of spleen cells from B6 Igh6−/− mice and Ii−/− mice (107 cells from each donor per recipient). All cells were injected i.p. One day later the reconstituted mice, B6+/+ mice (n = 5), and nonmanipulated B6 SCID mice (No Tx; n = 5) were infected with 50 B. pahangi L3. Mice were necropsied at 2 weeks postinfection and worm burdens were quantitated as described in the text.

In addition to MHC II expression, mouse B lymphocytes can express the nonclassical antigen-presenting molecule CD1 (7). Infection of B6 CD1−/− mice with B. pahangi L3 resulted in rapid parasite clearance of the parasites, similar to what we observe in B6+/+ mice (data not shown).

The role of antibody in protection against Brugia infection in mice.

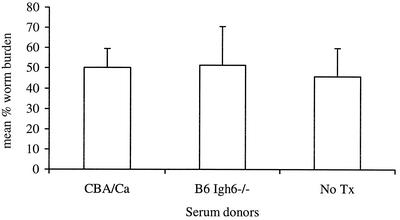

Transfer of protection against infection with serum from individuals that have recovered from an infection is a classic way to confirm the role of humoral immunity in host protection (3, 15, 16, 21). We used this approach to demonstrate a role for humoral immunity in Brugia infection in mice. CBA/Ca mice were immunized with B. pahangi L3 and bled 3 weeks postinfection. Serum was pooled from 35 immunized mice and injected i.p. into CBA/N recipients at days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 postinfection with B. pahangi L3. One control group received pooled serum from B. pahangi-immunized B6 Igh6−/− mice following the same schedule. A control cage of CBA/N mice was infected with B. pahangi L3 and received no other treatment. All mice were necropsied at 14 days postinfection. Figure 10 shows that all three groups had similarly high worm recoveries. Thus, whole serum transfer did not decrease the worm burdens in CBA/N mice.

FIG. 10.

Transfer of primed serum to CBA/N mice. Thirty-five CBA/Ca mice were immunized with 40 B. pahangi L3. Mice were bled by cardiac puncture at 3 weeks postinfection; serum was collected by centrifugation and pooled. Five CBA/Ca mice were infected with 45 B. pahangi L3 and injected i.p. with 240 μl (the volume-equivalent of serum that we usually recover from a single mouse) of pooled serum on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 postinfection. The control groups of CBA/N mice received no treatment (No Tx) or were injected with 240 μl of pooled serum from B. pahangi-infected B6 Igh6−/− mice (n = 5 for each group). All mice were necropsied on day 14 postinfection and worm burdens were quantitated.

Another possible way to address the protective function of antibody in the immune response is to investigate the role of Fc receptors. These receptors, when bound to antibody-antigen complexes, trigger various responses in the cells that include, among others, phagocytosis, degranulation, cytokine release, and downregulation or upregulation of cell activation. We investigated the ability of available Fc receptor-deficient mice to clear Brugia parasites. There are two mouse strains on the B6 background that have targeted deletions of an Fc receptor gene: B6.129P2-Fcgr3tm1Sjv mice, deficient in FcγRIII, and B6.129P2-Fcerg1tm1 mice, deficient in the γ chain subunit of the Fc receptor. The common γ chain of Fc receptors is expressed in FcɛRI, FcγRI, and FcγRIII (26). Both knockout strains cleared B. pahangi parasites with the same kinetics as B6+/+ mice (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our data indicate that mature B lymphocytes are required not only for the clearance of a primary Brugia infection but also for the accelerated response to a challenge infection with L3 larvae. There are two possible explanations for this observation. First, B lymphocytes and/or their products might be essential for killing the parasites and, in their absence, there is no compensatory factor to perform the same function. Conversely, it is possible that B lymphocytes are required for the induction and/or maintenance of immunological memory to the parasites. Interestingly, the inability of B-lymphocyte-deficient mice to reduce worm burdens during a secondary infection has been reported in several nematode infection models that do not manifest a role of B cells in a primary infection. Litomosoides sigmodontis infections showed no differences in parasite burdens between BALB/c wild-type and B-lymphocyte-deficient mice (18). However, whereas wild-type mice demonstrated 65% protection following vaccination with irradiated infective-stage larvae, Igh6−/− mice had similar worm burdens in primary and challenge infections. A similar observation was published for Schistosoma mansoni infection in mice. While vaccination with irradiated cercaria induced up to 80% resistance to reinfection in B6+/+ mice, the protection was significantly reduced in B6 Igh6−/− mice (13).

Our data strongly support the hypothesis that B lymphocytes, when primed, are capable of mediating protection against Brugia parasites. Although T cells are required for parasite clearance during a primary infection, they are not necessary for the final stage of Brugia parasite clearance in mice. A similar observation was reported for a mouse model of S. mansoni infection (14). In this model, mice that were treated with an antibody that depletes CD4+ T cells were permissive to infection with S. mansoni cercaria. However, if mice were immunized with irradiated infective-stage larvae prior to depletion of CD4+ cells, they remained resistant to the infection. While the parasite model and the methods used in this study are very different from ours, they support the same conclusion.

NUDE recipients of primed peritoneal B cells had a high percentage of IgE+ cells. Indeed, we find that in B6+/+ mice 40% of B cells are positive for surface IgE staining by 2 weeks postinfection (unpublished observation). Interestingly, another B-cell population that was markedly different in the recipients of primed B cells was the B1a lymphocyte population. The decrease of CD5+ B cells might be of functional importance. CD5 is a surface molecule that was originally discovered as a marker for a subset of T lymphocytes (12). On T cells, CD5 is believed to be important for negative regulation of TCR-mediated signal transduction (30). Similarly, CD5 appears to be a negative regulator of B-cell receptor (BCR)-mediated signal transduction (5). Unlike splenic B cells, peritoneal CD5+ B lymphocytes undergo apoptosis when stimulated through the surface IgM receptor (5, 24). In contrast, in the absence of CD5, BCR stimulation drives B1 lymphocytes into proliferation. It is possible that the decrease in the proportion of peritoneal B1a cells following Brugia infection is an important step that aims to maximize B-lymphocyte proliferation and responses. In this light, the observation that the proportion of B1a cells goes up in BALB/c but not in B6 mice infected with S. mansoni (23) might indicate one (of many) possible mechanism that underlies the well-established phenomenon of BALB/c mice being more permissive to infection with metazoan pathogens, such as Brugia, Litomosoides, or Schistosoma.

Although we did not find significant differences in peritoneal cell numbers between uninfected B6+/+ and B6 JHD or B6 Igh6−/− mice, B-cell-deficient mice demonstrated clear defects in T-cell and eosinophil recruitment to the peritoneal cavity following infection with the parasites. Since eosinophil recruitment in this infection model appears to be dependent on T lymphocytes, it is possible that the lower numbers of eosinophils in JHD mice are due to the defect in T-lymphocyte function and not to the absence of B lymphocytes.

B-lymphocyte-deficient mice demonstrated a defect in Th2 polarization in the peritoneal cavity and a higher expression of gamma interferon mRNA by peritoneal cells, compared to wild-type mice. IL-4 and IL-5 production is known to be protective in experimental filarial infection models (1, 17, 27), whereas IL-13 plays a role in protection against gastrointestinal nematodes (9). Since wild-type mice demonstrated strong expression of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 mRNA by peritoneal cells on day 1 postinfection, it is possible that very early production of these cytokines in the peritoneal cavity is critical for the Th2 polarization of the immune response and for the clearance of the parasites. We do not have, however, data to indicate that peritoneal B lymphocytes are the source of these cytokines. Since peritoneal B lymphocytes have been shown to secrete IL-10 in response to the nonprotein schistosomal antigens, similar secretion of IL-10 following exposure to filarial parasites may be an important factor for Th2 polarization of the immune response in the Brugia mouse infection model.

While in our hands serum transfer failed to protect CBA/N mice from Brugia parasites, we cannot rule out the protective role of antibody in Brugia infection. It is not known which antibody isotype(s) might be protective and how much antibody actually stays in the peritoneal cavity after injection. In addition, if CBA/N mice have defects other than antibody production, serum transfer might not be able to compensate for them.

In conclusion, the data presented herein demonstrate the transfer of protection against Brugia infection with peritoneal B lymphocytes from primed mice. Although the production of antibodies has traditionally been thought to be the primary role of B cells in the immune response, our data indicate that B lymphocytes may be critical for proper cell recruitment to the site of infection and for the initiation of Th2-like responses in the peritoneal cavity.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Qaoud, K. M., E. Pearlman, T. Hartung, J. Klukowski, B. Fleischer, and A. Hoerauf. 2000. A new mechanism for IL-5-dependent helminth control: neutrophil accumulation and neutrophil-mediated worm encapsulation in murine filariasis are abolished in the absence of IL-5. Int. Immunol. 12:899-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. 2001. Lymphatic filariasis. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 76:149-154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arulanandam, B. P., J. M. Lynch, D. E. Briles, S. Hollingshead, and D. W. Metzger. 2001. Intranasal vaccination with pneumococcal surface protein A and interleukin-12 augments antibody-mediated opsonization and protective immunity against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Infect. Immun. 69:6718-6724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bancroft, A. J., R. K. Grencis, K. J. Else, and E. Devaney. 1994. The role of CD4 cells in protective immunity to Brugia pahangi. Parasite Immunol. 16:385-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bikah, G., J. Carey, J. R. Ciallella, A. Tarakhovsky, and S. Bondada. 1996. CD5-mediated negative regulation of antigen receptor-induced growth signals in B-1 B cells. Science 274:1906-1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bikoff, E. K., L. Y. Huang, V. Episkopou, J. van Meerwijk, R. N. Germain, and E. J. Robertson. 1993. Defective major histocompatibility complex class II assembly, transport, peptide acquisition, and CD4+ T cell selection in mice lacking invariant chain expression. J. Exp. Med. 177:1699-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brossay, L., D. Jullien, S. Cardell, B. C. Sydora, N. Burdin, R. L. Modlin, and M. Kronenberg. 1997. Mouse CD1 is mainly expressed on hemopoietic-derived cells. J. Immunol. 159:1216-1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlow, C. K., and M. Philipp. 1987. Protective immunity to Brugia malayi larvae in BALB/c mice: potential of this model for the identification of protective antigens. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 37:597-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grencis, R. K. 2001. Cytokine regulation of resistance and susceptibility to intestinal nematode infection—from host to parasite. Vet. Parasitol. 100:45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grusby, M. J., R. S. Johnson, V. E. Papaioannou, and L. H. Glimcher. 1991. Depletion of CD4+ T cells in major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient mice. Science 253:1417-1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris, D. P., L. Haynes, P. C. Sayles, D. K. Duso, S. M. Eaton, N. M. Lepak, L. L. Johnson, S. L. Swain, and F. E. Lund. 2000. Reciprocal regulation of polarized cytokine production by effector B and T cells. Nat. Immunol. 1:475-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herzenberg, L. A., and A. B. Kantor. 1992. Layered evolution in the immune system. A model for the ontogeny and development of multiple lymphocyte lineages. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 651:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jankovic, D., T. A. Wynn, M. C. Kullberg, S. Hieny, P. Caspar, S. James, A. W. Cheever, and A. Sher. 1999. Optimal vaccination against Schistosoma mansoni requires the induction of both B cell- and IFN-gamma-dependent effector mechanisms. J. Immunol. 162:345-351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly, E. A., and D. G. Colley. 1988. In vivo effects of monoclonal anti-L3T4 antibody on immune responsiveness of mice infected with Schistosoma mansoni. Reduction of irradiated cercariae-induced resistance. J. Immunol. 140:2737-2745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kennedy, B. J., L. A. Novotny, J. A. Jurcisek, Y. Lobet, and L. O. Bakaletz. 2000. Passive transfer of antiserum specific for immunogens derived from a nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae adhesin and lipoprotein D prevents otitis media after heterologous challenge. Infect. Immun. 68:2756-2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim, I. J., E. Flano, D. L. Woodland, and M. A. Blackman. 2002. Antibody-mediated control of persistent gamma-herpesvirus infection. J. Immunol. 168:3958-3964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin, C., K. M. Al-Qaoud, M. N. Ungeheuer, K. Paehle, P. N. Vuong, O. Bain, B. Fleischer, and A. Hoerauf. 2000. IL-5 is essential for vaccine-induced protection and for resolution of primary infection in murine filariasis. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. (Berlin) 189:67-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin, C., M. Saeftel, P. N. Vuong, S. Babayan, K. Fischer, O. Bain, and A. Hoerauf. 2001. B-cell deficiency suppresses vaccine-induced protection against murine filariasis but does not increase the recovery rate for primary infection. Infect. Immun. 69:7067-7073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCall, J. W., J. B. Malone, A. Hyong-Sun, and P. E. Thompson. 1973. Mongolian jirds (Meriones unguiculatus) infected with Brugia pahangi by the intraperitoneal route: a rich source of developing larvae, adult filariae, and microfilariae. J. Parasitol. 59:436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson, F. K., D. L. Greiner, L. D. Shultz, and T. V. Rajan. 1991. The immunodeficient scid mouse as a model for human lymphatic filariasis. J. Exp. Med. 173:659-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishimura, Y., T. Igarashi, N. Haigwood, R. Sadjadpour, R. J. Plishka, A. Buckler-White, R. Shibata, and M. A. Martin. 2002. Determination of a statistically valid neutralization titer in plasma that confers protection against simian-human immunodeficiency virus challenge following passive transfer of high-titered neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 76:2123-2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paciorkowski, N., P. Porte, L. D. Shultz, and T. V. Rajan. 2000. B1 B lymphocytes play a critical role in host protection against lymphatic filarial parasites. J. Exp. Med. 191:731-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palanivel, V., C. Posey, A. M. Horauf, W. Solbach, W. F. Piessens, and D. A. Harn. 1996. B-cell outgrowth and ligand-specific production of IL-10 correlate with Th2 dominance in certain parasitic diseases. Exp. Parasitol. 84:168-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pers, J. O., C. Jamin, R. Le Corre, P. M. Lydyard, and P. Youinou. 1998. Ligation of CD5 on resting B cells, but not on resting T cells, results in apoptosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:4170-4176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajan, T. V., L. Ganley, N. Paciorkowski, L. Spencer, T. R. Klei, and L. D. Shultz. 2002. Brugian infections in the peritoneal cavities of laboratory mice: kinetics of infection and cellular responses. Exp. Parasitol. 100:235-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravetch, J. V. 1994. Fc receptors: rubor redux. Cell 78:553-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spencer, L., L. Shultz, and T. V. Rajan. 2001. Interleukin-4 receptor-Stat6 signaling in murine infections with a tissue-dwelling nematode parasite. Infect. Immun. 69:7743-7752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suswillo, R. R., M. J. Doenhoff, and D. A. Denham. 1981. Successful development of Brugia pahangi in T-cell deprived CBA mice. Acta Trop. 38:305-308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suswillo, R. R., D. G. Owen, and D. A. Denham. 1980. Infections of Brugia pahangi in conventional and nude (athymic) mice. Acta Trop. 37:327-335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarakhovsky, A., S. B. Kanner, J. Hombach, J. A. Ledbetter, W. Muller, N. Killeen, and K. Rajewsky. 1995. A role for CD5 in TCR-mediated signal transduction and thymocyte selection. Science 269:535-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vickery, A. C., J. K. Nayar, and K. H. Albertine. 1985. Differential pathogenicity of Brugia malayi, B. patei and B. pahangi in immunodeficient nude mice. Acta Trop. 42:353-363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vickery, A. C., A. L. Vincent, and W. A. Sodeman, Jr. 1983. Effect of immune reconstitution on resistance to Brugia pahangi in congenitally athymic nude mice. J. Parasitol. 69:478-485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vincent, A. L., W. A. Sodeman, and A. Winters. 1980. Development of Brugia pahangi in normal and nude mice. J. Parasitol. 66:448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vincent, A. L., A. C. Vickery, A. Winters, and W. A. Sodeman, Jr. 1982. Life cycle of Brugia pahangi (Nematoda) in nude mice, C3H/HeN (nu/nu). J. Parasitol. 68:553-560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yates, J. A., K. A. Schmitz, F. K. Nelson, and T. V. Rajan. 1994. Infectivity and normal development of third stage Brugia malayi maintained in vitro. J. Parasitol. 80:891-894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zimecki, M., P. J. Whiteley, C. W. Pierce, and J. A. Kapp. 1994. Presentation of antigen by B cells subsets. I. Lyb-5+ and Lyb-5− B cells differ in ability to stimulate antigen specific T cells. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 42:115-123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]