Abstract

IRS24 is a DNA damage-sensitive strain of Deinococcus radiodurans strain 302 carrying a mutation in an uncharacterized locus designated irrE. Five overlapping cosmids capable of restoring ionizing radiation resistance to IRS24 were isolated from a genomic library. The ends of each cloned insert were sequenced, and these sequences were used to localize irrE to a 970-bp region on chromosome I of D. radiodurans R1. The irrE gene corresponds to coding sequence DR0167 in the R1 genome. The irrE gene encodes a 35,000-Da protein that has no similarity to any previously characterized peptide. The irrE locus of R1 was also inactivated by transposon mutagenesis, and this strain was sensitive to ionizing radiation, UV light, and mitomycin C. Preliminary findings indicate that IrrE is a novel regulatory protein that stimulates transcription of the recA gene following exposure to ionizing radiation.

The bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans is known for its tolerance to many DNA-damaging agents, but it is its unusually high resistance to the lethal and mutagenic effects of ionizing radiation that distinguishes this species from other organisms (3, 5, 17, 20, 24). Exponential-phase cultures of D. radiodurans R1 survive exposure to gamma radiation at doses as high as 5,000 Gy without loss of viability or evidence of DNA damage-induced mutation (23). A 5,000-Gy dose of gamma radiation should introduce not less than 130 DNA double-strand breaks into each copy of the D. radiodurans R1 genome present within the irradiated cell (6), and direct measurements of ionizing radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks indicate that D. radiodurans suffers this level of DNA damage (13, 18). The mechanisms responsible for the DNA damage resistance of this species remain unknown.

As part of an effort to obtain a better understanding of the ionizing radiation resistance of D. radiodurans R1, this laboratory isolated 41 ionizing radiation-sensitive (IRS1 to -41) derivatives of D. radiodurans 302 (uvrA1) (29). Strain 302 is approximately 50 times more mutable than the wild-type R1 strain following N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) treatment, because it is incapable of carrying out nucleotide excision repair (19). This defect prevents effective repair of base damage caused by the alkylating agent. These IRS strains were placed into 16 linkage groups designated irrA to irrP (19). Each linkage group is presumed to include mutations that adversely affect a single gene or operon necessary for ionizing radiation resistance. In this study, we characterize IRS24, the sole strain that defines the irrE linkage group, establishing that irrE encodes a hypothetical protein identified as DR0167 in the genome sequence (http://www.tigr.org/tigr-scripts/CMR2/GenomePage3.spl?database=gdr). Compared with its parent strain, an irrE strain displays a dramatic increase in sensitivity to ionizing radiation, UV light, and mitomycin C, suggesting that this gene product plays a central regulatory role in DNA damage repair in D. radiodurans R1. Evidence is presented that loss of IrrE results in a decrease in recA expression following the cell's exposure to ionizing radiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. All D. radiodurans strains were grown at 30°C in TGY broth (0.5% tryptone, 0.3% yeast extract, 0.1% glucose) or on TGY agar (1.5% agar). Some D. radiodurans strains were also grown in a modified defined medium. The composition of the defined medium is as follows (all values are amounts added per liter of 10 mM phosphate buffer [pH 7.0 to 7.2]): 5 g of glucose, 0.4 mg of niacin, 0.5 mg of biotin, 100 mg of glutamate, 100 mg of methionine, 0.33 g of ammonium sulfate, 10 mg of CaCl2, 2.5 mg of FeSO4 · 7H2O, 100 mg of MgCl2 · 6H2O, 0.5 μg of CuSO4 · 5H2O, 10 μg of MnCl2 · 4H2O, 200 μg of ZnSO4 · 7H2O, and 20 μg of CoCl2. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB plates at 37°C. Plasmids were routinely propagated in E. coli strain DH5α MCR.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| D. radiodurans | ||

| R1 | ATCC 13939 | 1 |

| 302 | R1, but uvrA1 | 23 |

| IRS24 | 302, but irrE1 | 19 |

| AE1012 | IRS24, but irrE+ | This study |

| LSU2030 | R1, but irrE2::TnDrCat | This study |

| LS18 | R1, but streptomycin resistant | 29 |

| E. coli DH5α MCR | F mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80 lacZΔ15 ΔlacX74 endA1 recA1 deoR Δ(ara-leu)7697 araD139 galU galK nupG rpsL | Invitrogen, Inc., Grand Island, N.Y. |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T | Promega, Madison, Wis. | |

| pDONR 201 | Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif. | |

| pMM1 | pWE15::irrE+, ∼40-kb cosmid clone from D. radiodurans R1 (chromosome I positions 147109-187431) | This study |

| pMM2 | pWE15::irrE+, ∼39-kb cosmid clone from D. radiodurans R1 (chromosome I positions 149888-189320) | This study |

| pMM3 | pWE15::irrE+, ∼38-kb cosmid clone from D. radiodurans R1 (chromosome I positions 160082-197803) | This study |

| pMM4 | pWE15::irrE+, ∼37-kb cosmid clone from D. radiodurans R1 genomic DNA carrying irrE gene (chromosome I positions 169702-198400) | This study |

| pMM5 | pWE15::irrE+, ∼38-kb cosmid clone from D. radiodurans R1 (chromosome I positions 142682-180444) | This study |

| pUvrA1 | pGEM-T derivative with 3,441 bp of uvrA1 and its adjacent region (Ampr) | 10 |

| pDR0167 | pDONR 201 derivative with irrE coding sequence | This study |

| pGPS3 | Ampr Kanr | New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass. |

| pGTC101 | pGPS3 derivative with a TnDrCat insert, Catr Kanr Ampr | 10 |

Plasmid isolation.

Plasmids were isolated with the Miniprep kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, Calif.) or an alkaline lysis procedure (2).

Transformation in liquid culture.

D. radiodurans is relatively easy to manipulate using natural transformation. Fully competent throughout its exponential growth, D. radiodurans readily takes up and incorporates transforming DNA into its chromosome with high efficiency (19). Calcium chloride from a 1 M stock solution was added to D. radiodurans cultures in exponential growth (approximately 2 × 107 CFU/ml) until a final concentration of 30 mM was achieved. Following an 80-min incubation at 30°C, transforming DNA, either 1 μg of plasmid DNA or 10 μg of chromosomal DNA, was added to 1 ml of the CaCl2-treated culture. This mixture was held on ice for 30 min before being diluted 10-fold with TGY broth and incubated for 18 h at 30°C.

Dot transformation.

Twenty-five milliliters of an exponential-phase D. radiodurans culture was harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Pellets were reconstituted in 2.5 ml of 10 mM MgSO4. A 100-μl aliquot of the reconstituted cells was spread onto a TGY agar plate and incubated at 30°C for 2 h. Transforming DNA was dotted directly onto the surface of the plate in a 5- to 10-μl aliquot and allowed to dry. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 18 to 24 h and replica plated onto TGY agar. Selective pressure was applied to the replica to identify successful transformants. To select mitomycin C-resistant transformants, lawns were replica plated onto TGY agar containing 60 ng of mitomycin C per ml. To select for ionizing radiation-resistant transformants, lawns were replica plated onto TGY agar and irradiated at 10,000 Gy. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 3 days before being scored for survival within the area where the DNA had been dotted.

Chromosomal DNA isolation.

TGY broth (200 ml) was inoculated with a 2-ml culture (2 × 107 CFU/ml) of D. radiodurans. After 48 h, the 200-ml cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C at 6,000 × g for 15 min. Pellets were resuspended in 20 ml of 95% ethanol and held at room temperature for 10 min to remove the D. radiodurans outer membrane. The ethanol-stripped cells were collected by centrifugation at 4°C at 6,000 × g for 15 min, and the resulting pellet was gently resuspended in 1 ml of 2-mg/ml lysozyme (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Mo.) in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). This mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Five milliliters of pronase E solution (0.8 mg of pronase E per ml [Sigma Chemical], 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 0.1 M EDTA) was added to lysozyme-treated cells and incubated for at least 3 h at 50°C. Lysed cells were transferred to a centrifuge tube and extracted once with an equal volume of phenol-chloroform (1:1) and twice with equal volumes of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1). The DNA was precipitated from the extracted material with 1 ml of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 7.0) and 20 ml of ice-cold 100% ethanol. The DNA was spooled out with a curved glass rod and washed twice with 70% ethanol. The DNA was air dried and dissolved in 5 ml of TE buffer (pH 8.0) and stored at 4°C.

Survival curves.

Only D. radiodurans cultures in exponential growth (106 to 107 CFU/ml) were evaluated for their ability to survive UV or ionizing radiation. All D. radiodurans cultures were treated at 25°C. UV irradiation was administered with a germicidal lamp with a calibrated dose rate of 25 J of generated UV light/m2/s. Gamma irradiation was conducted with a model 484R 60Co irradiator (J. L. Shepherd & Associates, San Fernando, Calif.) at a rate of 30 Gy/min. Irradiated cultures were diluted, plated in triplicate on TGY agar plates, and incubated for 3 days at 30°C before scoring for survivors.

Amplification of the irrE sequence and DNA sequencing.

Genomic DNA from appropriate D. radiodurans strains was used as the template to generate the PCR products used for DNA sequencing. Amplification was accomplished with two sets of primers: (i) IRS241up (5′-CACCCCTTGCTTCGCAAGGCCTTCTCTGC-3′) and IRS241down (5′-CTTCCATGCCCGTGGCGAGGGCAAGCGCCG-3′), which generate a 1,030-bp PCR fragment, and (ii) IRS242up (5′-GGTAAGTGGCGGGTTGTTTGGTCTGGAGGC-3′) and IRS242down (5′-CGTAGAGCGCCGACGACGCGCTGACTTCGG-3′), which generate an 840-bp PCR fragment. PCR products were purified with the Prep-A-Gene DNA purification system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), following the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR products were then sequenced with an ABI PRISM dye terminator terminal sequencing system, available through the Perkin-Elmer Corporation (Foster City, Calif.). Reactions were analyzed with an ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

The construction of pDR0167.

A PCR fragment the irrE gene (DR0167) of D. radiodurans R1 was amplified directly from purified chromosomal DNA with a pair of primers derived from the published sequence of the R1 genome (http://www.tigr.org/tigr-scripts/CMR2/GenomePage3.spl?database=gdr). Primers DR0167up (5′ GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTATGTGCC 3′) and DR0167down (5′ GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTTTCACTG 3′) were designed for amplification and cloning of the irrE coding sequence into the GATEWAY cloning system (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.). The irrE-containing PCR fragment was inserted directly into the vector pDONR201 (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.) to generate the construct pDR0167. The insert was sequenced and found to be identical to that of locus DR0167 in the TIGR database.

In vitro transposition.

An in vitro transposition protocol (10) developed specifically for use with D. radiodurans was used to disrupt the irrE coding sequence in D. radiodurans R1. Twenty nanograms of purified, circular pGTC101, a derivative of pGPS3, was combined with commercially available TnsABC∗ transposase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) and pDR0167 (4:1 molar ratio of pGTC101 to pDR0167). The transposition reaction mixture was transformed by heat shock into approximately 5 × 105 CFU of DH5α MCR. Successful transposon insertions into the target were selected by plating the transformed cells onto LB medium containing 25 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. Seventy of the Catr colonies were picked, and the plasmids they carried were isolated. These plasmids were digested with a combination of ApaI and PstI to release the gene of interest from the vector. Digestions were separated on 1% agarose and stained to confirm that the transposon had inserted into irrE.

One microgram of ApaI-linearized plasmid was added to competent cultures of D. radiodurans R1 (approximately 107 CFU/ml). After an 8-h incubation, 300 μl of the transformation mixture was plated onto TGY agar plates containing 5 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. Individual colonies were used to inoculate TGY broth containing 5 μg of chloramphenicol per ml, and cultures were grown to the stationary phase. One hundred microliters of this broth culture was used to inoculate TGY broth containing 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml, and cultures were grown to the stationary phase. This culture was diluted (1 in 106) and plated on TGY agar containing10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. Transposon insertions into irrE were verified by PCR. The set of primers designed to amplify irrE, DR0167up and DR0167down, was combined with a primer (Primer S) that anneals within the transposon as described previously. The full-length 1,045-bp fragment corresponding to the amplified irrE sequence could not be detected when all three primers were present. However, a shorter (650-bp) fragment was obtained, indicating that the transposon had inserted into irrE. This short fragment had a sequence identical to the 3′ end of DR0167. The transposon inserted between nucleotides 459 to 460 of the irrE coding sequence. The strain containing the disruption was designated LSU2030.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from 1-liter cultures of irradiated and nonirradiated exponential-phase D. radiodurans cells with TRI reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, Ohio) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cell disruption was accomplished by adding 100 μl of 0.1-mm-diameter zirconia-silica beads (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, Okla.) and TRI reagent to the cell paste from 1 liter of cells and vigorously agitating this mixture for 6 min with a vortex mixer. Total RNA from each sample condition was treated with 10 U of DNase I (Ambion, Austin, Tex.) and purified with RNeasy Minikit columns (QIAGEN). RNA quality and quantity were evaluated spectrophotometrically by determining A260 and A280.

Two micrograms of each DNase I-treated, purified RNA sample was converted to cDNA by using SUPERSCRIPT II RNase H− reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) combined with 25 pmol of random hexamers to initiate synthesis. Conditions for this reaction followed the manufacturer's instructions.

Approximately 100 bp of unique sequence from the genes encoding RecA (DR2340) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (DR1343) were amplified using the following primer sets: DR2340up (5′GTCAGCACCGGCAGCCTCAGCCTTGACCTC3′) and DR2340dwn (5′GATGGCGAGGGCCAGGGTGGTCTTGC3′) and DR1343up (5′CTTCACCAGCCGCGAAGGGGCCTCCAAGC3′) and DR1343dwn (5′GCCCAGCACGATGGAGAAGTCCTCGCC3′). The PCR mixture (50 μl) for amplifying these genes contained the appropriate primers at a final concentration of 0.2 μM, 1 μl of the cDNA template and SYBR Green PCR Core Reagents (Applied Biosystems). Amplifications were carried out by incubating reaction mixtures at 95°C for 3 min prior to 40 cycles of 30 s at 95°C followed by 30 s at 65°C and 30 s at 72°C. Data were collected and analyzed at each 72°C interval. Amplification was followed by melting curve analysis and consisted of 80 cycles, starting at 55°C, with 0.5°C increments/cycle at 10-s intervals. Reactions were then held at 23°C until analysis.

Results for each 96-well plate consisted of standard curves for each primer set run in duplicate. Standard curves were constructed with cDNA obtained from the unirradiated wild-type organism. A dilution series (1 to 1 × 10−4) of each experimental sample was generated and run in duplicate. Negative controls without cDNA template were run on every plate analyzed.

All assays were performed with the iCycler iQ Real-Time Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). All data were PCR baseline subtracted before threshold cycle values were designated and standard curves were constructed. Mean concentrations of recA transcript in each sample were calculated from the standard curves generated with the DR2340 primer set. Induction levels were determined by dividing the calculated concentration of transcript from the irradiated sample by the concentration of transcript from the unirradiated sample for each strain. The mean concentration of the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gap) transcript, a housekeeping gene whose expression is unaffected by ionizing radiation, was also determined before and after irradiation for each strain.

RESULTS

IRS24 is sensitive to the lethal effects of ionizing radiation and UV light.

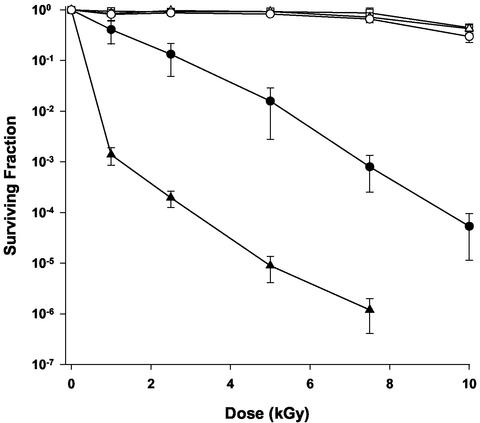

IRS24 was isolated when colonies from mutagenized cultures of D. radiodurans strain 302 (uvrA1) were screened for sensitivity to 5,000 Gy of gamma radiation (29). Subsequent linkage analysis revealed that IRS24 carried a defect in a locus tentatively designated irrE (19). In Fig. 1, the ionizing radiation resistance of IRS24 is compared with those of 302 and the R1 type strain. As reported previously, strains 302 and R1 demonstrate no loss of viability at doses below 5,000 Gy, whereas IRS24 exhibits significantly lower levels of survival over the entire dose range tested. The shoulder of resistance characteristic of the parent strain is completely absent, and only 1% of gamma-irradiated IRS24 cultures survive the 5,000-Gy dose.

FIG. 1.

Representative survival curves for D. radiodurans strain IRS24 irrE1 uvrA1 (closed circles) and LSU2030 irrE2::TnDrCat (closed triangles) following exposure to gamma radiation. Survival of strains R1 (open squares), AE1012 (IRS24 transformed to irrE+ with pMM1) (open triangles), and 302 uvrA1 (open circles) are also shown. Values are the means ± standard deviations of triplicate experiments. (n = 9).

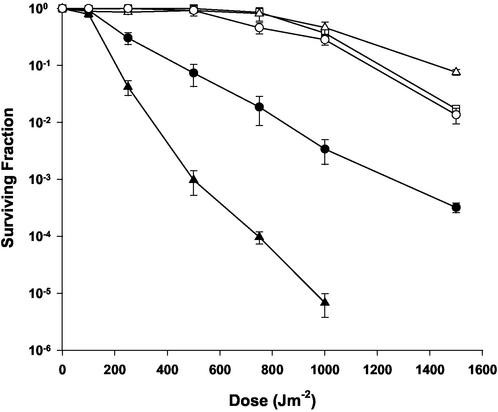

The survival curves generated following exposure to UV light for 302, R1, and IRS24 are plotted in Fig. 2. Strain 302 displays wild-type resistance, exhibiting 100% survival at the 500-J m−2 dose. The survival curve for IRS24 has a small shoulder of resistance, but at doses above 250 J m−2, cultures are substantially more sensitive to UV relative to the parent strain. For example, at 500 J m−2, IRS24 cultures display approximately 5% survival.

FIG. 2.

Representative survival curves for D. radiodurans strain IRS24 irrE1 uvrA1 (closed circles) and LSU2030 irrE2::TnDrCat (closed triangles) following exposure to UV light. Survival of strains R1 (open squares), AE1012 (IRS24 transformed to irrE+ with pMM1) (open triangles), and 302 uvrA1 (open circles) are also shown. Values are the means ± standard deviations of triplicate experiments (n = 9).

Genetic inactivation of irrE is sufficient to sensitize strain 302 to the lethal effects of ionizing radiation and UV light.

A pWE15 cosmid library was screened for clones that could restore ionizing radiation resistance to IRS24. Individual cosmids were isolated and aliquots of these purified cosmids, which have an average insert size of 40 kb, were pooled in groups of 10. The pooled cosmids were dotted in an identifiable pattern onto an agar plate freshly spread with approximately 105 CFU of an exponentially growing IRS24 culture. Since D. radiodurans cultures are naturally competent throughout exponential-phase growth, the cosmid DNA is taken up and homologous sequences are integrated into the IRS24 genome. The lawn that formed following transformation was replica plated and subjected to 7,500 Gy of gamma radiation. When the defect in IRS24 was corrected following the transformation protocol, a patch of cells appeared on the irradiated plate at the site where a pool of cosmids had been dotted. Being sensitive to ionizing radiation, the background lawn fails to grow, making identification of clones carrying genes that restore radioresistance straightforward. This protocol was repeated with the individual cosmids that made up each pool. After 300 cosmids were screened, five clones capable of restoring IRS24 to ionizing radiation resistance were identified and labeled pMM1 to -5.

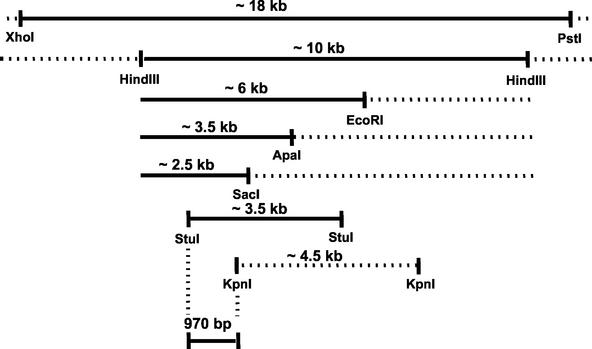

Primers specific for the T3 and T7 promoters that flank the site of the insert in pWE15-derived cosmid clones were used to obtain approximately 200 bp of sequence from both ends of the inserts in pMM1 to -5. (The positions corresponding to each end of the inserts found in these cosmids are given in Table 1.) By matching these sequences to the D. radiodurans genome sequence available through TIGR, it was possible to localize the site of the mutation. The inserts in all five cosmids overlap, and alignment of their sequences revealed that they share an 18-kb XhoI-PstI fragment. These restriction sites are located on D. radiodurans R1 chromosome I at positions 161626 and 179773, respectively. This region contains 20 open reading frames (ORFs) annotated as DR0160 to -179. It was assumed that the irrE gene was located within this 18-kb fragment, since this region of the chromosome did not include the coding sequence for uvrA1.

IRS24 was transformed to radioresistance with pMM1, generating strain AE1012. Characterization of this strain reveals that returning wild-type irrE to IRS24 fully restores UV and ionizing radiation resistance (Fig. 1 and 2). AE1012 remains sensitive to mitomycin C, indicating that this strain retains the parental uvrA1 defect. We conclude that the loss of irrE was solely responsible for the increased UV and ionizing radiation sensitivity of IRS24.

The irrE mutation maps to an open reading frame designated DR0167.

Using the genome sequence available through TIGR, a restriction map was generated for the insert in pMM1, one of the cosmids containing the irrE gene. Using this map as a guide, pMM1 was subjected to a series of restriction digests that reduced the XhoI-PstI fragment into smaller overlapping fragments. These digests were separated on a 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide, and specific bands were excised from the gel and purified. An attempt was made to transform IRS24 to ionizing radiation resistance with these restriction fragments by using the dot transformation protocol described above. Figure 3 schematically illustrates the outcome of this analysis, which eventually localized irrE to a 960-bp sequence that included 791 bp of the 5′ end of a hypothetical ORF designated DR0167 and 170 bp of sequence upstream of this gene. To verify that this region contained irrE, a 1,065-bp PCR product including this 970-bp sequence was generated from R1 chromosomal DNA and used to successfully transform IRS24 to ionizing radiation resistance.

FIG. 3.

Diagrammatic representation of restriction fragments (solid lines) capable of transforming IRS24 to ionizing radiation resistance. Dashed lines define fragments that could not transform IRS24 to radioresistance.

DR0167 is the first ORF in what appears to be a four-gene operon (Fig. 4) containing homologues of three genes (folP, folB, and folK) in the folate biosynthetic pathway described in other prokaryotes. The last nucleotide of DR0167 overlaps the first nucleotide of the start codon for folP, followed by a 24-nucleotide intergenic region between folP and folB. The folB and folK genes also overlap by 1 nucleotide. Since IRS24 is capable of growing in a defined medium that lacks folate (data not shown), DR0167 does not appear to be necessary for folate biosynthesis.

FIG. 4.

Regional view of D. radiodurans R1 chromosome I depicting location of DR0167.

IRS24 carries a missense mutation in locus DR0167.

Genomic DNA was isolated from IRS24 and the parent strain, 302. Primers specific for DR0167 and the upstream sequence were made and used to amplify the region of interest from the mutant and parent strains. PCR products from four independent amplification reactions were sequenced in both directions and examined for differences. The sequence of DR0167 in 302 is identical to that reported in the TIGR genome sequence. IRS24 has a 1-bp change within the coding sequence of DR0167 relative to the parent strain 302. There is a GC224-AT transition mutation in codon 111 of DR0167, causing an arginine-to-cysteine amino acid change in the protein. Otherwise the two sequences are identical. This allele was designated irrE1.

Disruption of irrE sensitizes D. radiodurans R1 to the lethal effects of mitomycin C.

Attempts to transform IRS24 to mitomycin C resistance with pUvrA1, a plasmid carrying the wild-type uvrA1 gene, were unsuccessful, suggesting that a defect in irrE may also sensitize the strain to this cross-linking agent. To test this possibility, the irrE gene was disrupted in wild-type D. radiodurans R1 by insertional mutagenesis with the transposon TnDrCat (10). The resulting strain, LSU2030 (irrE2::TnDrCat), cannot grow in the presence of 60 ng of mitomycin C per ml, whereas growth of R1 is unaffected by this concentration of the antibiotic, indicating that the IrrE protein is also necessary for this species' resistance to mitomycin C. LSU2030 will grow in defined medium lacking folate (data not shown) with the same kinetics as the wild-type strain, indicating that the transposon is not exerting a negative polar effect on the downstream ORFs putatively involved in folate biosynthesis.

LSU2030 is extremely sensitive to ionizing radiation (Fig. 1). Disruption of irrE resulted in a 1,000-fold increase in sensitivity to gamma radiation relative to R1 at the 1,000-Gy dose. At 5,000 Gy, LSU2030 was 5 orders of magnitude more sensitive than R1. LSU2030 is also sensitive to UV (Fig. 2), confirming that the irrE gene product is a necessary component for UV resistance in D. radiodurans R1. As observed for IRS24, there is a modest resistance to UV after exposure to 100 J of UV m−2, but at higher doses, there is a precipitous drop in viability within the irradiated LSU2030 cultures relative to R1, the parent strain. At 500 J m−2, LSU2030 is approximately 1,000-fold more sensitive to UV than R1.

These observations indicate that the irrE1 gene product retains some activity. The IRS24 strain is clearly better able to survive exposure to ionizing radiation and UV light than is LSU2030.

IrrE may contain a metalloprotease domain.

The IrrE peptide sequence was used as the query for an NCBI PSI-BLAST search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/), and the various sequences identified as having significant sequence similarity after all rounds of searching were collected and analyzed. In addition, the peptide sequence was used as a query for an NCBI CD-Search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) with the Expect value set to “100” and the Search mode set to “2-pass.” The best-scoring hit (E = 0.6) was to a domain of 1SMP, a zinc-dependent metalloprotease of known structure, suggesting that IrrE may exhibit protease activity. This region of similarity, which includes the expected zinc-binding site (HEXXH), is the most conserved region from the PSI-BLAST analysis. Determining whether IrrE is a protease awaits further investigation.

IRS24 and LSU2030 are capable of natural transformation.

An attempt was made to transform exponential-phase cultures of IRS24 and LSU2030 to streptomycin resistance (Strr) with genomic DNA isolated from LS18, a Strr strain of R1 (29). As indicated in Table 2, the IRS24 (irrE1) strain was transformed with efficiencies identical to those of LSU2030 and the uvrA1 strain AE1012. The transformation efficiencies exhibited by R1 were consistently twofold lower than those of the other strains, and at present, this cannot be explained. We conclude that inactivation of irrE fails to affect the cell’s ability to take up and incorporate DNA into its genome through homologous recombination, suggesting that the IrrE protein is not directly involved in RecA-mediated synapsis or the postsynaptic events necessary for successful completion of recombination during natural transformation.

TABLE 2.

Transformation efficiency of irrE strainsa

| Type of resistance | Transformation efficiency of strainb:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | LSU2030 | IRS24 | AE1012 | |

| Strr | 20 ± 1.9 | 51 ± 11 | 61 ± 20 | 43 ± 5.0 |

| Mtcr | —c | NDd | ND | 3 ± 0.2 |

See Table 1 for a description of the strains used in this analysis.

Values were calculated by dividing the number of drug-resistant transformants by the titer of the transformed culture and multiplying the quotient by 10−3 ± standard deviation. The numbers are the mean of nine measurements (three experiments with three replicates per experiment).

—, resistant to 60 ng of mitomycin C per ml. A transformation frequency cannot be determined.

ND, transformants not detected.

The IrrE protein stimulates recA expression following the cell's exposure to ionizing radiation.

In a recent study, Narumi and colleagues (26) reported that deinococcal recA gene expression was not regulated by the deinococcal LexA protein. However, RecA levels were shown to increase following exposure to ionizing radiation, suggesting that recA expression is regulated in D. radiodurans. To test the possibility that loss of IrrE might affect recA expression, changes in the level of recA transcript were monitored with quantitative real-time PCR. RNA was isolated from cultures of R1 and LSU2030 (irrE2::TnDrCat) before and 0.5 h after exposure to 3,000 Gy of gamma radiation. Concentrations of the recA transcript were determined for irradiated and unirradiated cultures in three independent experiments. Changes in recA expression were evaluated by dividing the transcript concentration obtained following irradiation by the concentration obtained prior to irradiation. The means of the quotients obtained are graphically represented in Fig. 5. In R1, recA transcript increased 12.6-fold in irradiated cultures relative to levels of recA transcript detected in unirradiated cultures. In contrast, the mean recA level increased only 2.6-fold in LSU2030 cultures following irradiation, indicating that the irrE gene product strongly influences recA expression in D. radiodurans. In comparison, the levels of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gap) induction for R1 and LSU2030 were indistinguishable from one another, with a slight repression in gap transcript level following irradiation. It appears that IrrE has a regulatory function, serving as a positive effector of gene expression for at least recA.

FIG. 5.

Relative expression of recA and gap in R1 (black) and LSU2030 irrE2::TnDrCat (gray) following exposure to 3,000 Gy of gamma radiation. (Values greater than 1 represent an induction; values less than 1 represent repression of the transcript.) Values are the means ± standard deviations of triplicate experiments (n = 6).

DISCUSSION

Detailed examination of the genomic DNA sequence of D. radiodurans R1 has failed to provide any insights that help explain the DNA damage tolerance of this species (17, 30). The D. radiodurans genome encodes homologues of most of the characterized DNA repair proteins found in more radiosensitive prokaryotes, suggesting that D. radiodurans has unprecedented mechanisms for facilitating the cell's recovery from DNA damage (4). The key to these mechanisms may lie within the group of hypothetical proteins comprising approximately one-third of the predicted coding sequences in the D. radiodurans genome. By characterizing a collection of DNA damage-sensitive strains isolated from mutagenized cultures of D. radiodurans, we were able to identify one such gene, DR0167. This gene's importance in the overall stress response of D. radiodurans was first identified in strain IRS24, a derivative of 302 (19, 29). D. radiodurans strain 302 has a 144-bp deletion that removes the first 34 bp of the uvrA1 coding sequence and 110 bp of upstream sequence (25). This deletion sensitizes 302 to mitomycin C, but this strain exhibits wild-type resistance to ionizing radiation and UV light.

Preliminary characterization had established that IRS24 carries a mutation in a locus designated irrE that rendered 302 sensitive to ionizing radiation (19). This study began with the intent of identifying irrE. To accomplish this task, we took advantage of the D. radiodurans genome sequence and the efficiency of natural transformation in this species (28). A cosmid library generated from D. radiodurans R1 genomic DNA was transformed into competent IRS24 cultures and screened for clones capable of restoring ionizing radiation resistance to the strain. Five clones were identified and sequencing the ends of the inserts in each cosmid revealed that (i) all five inserts overlapped and (ii) none of the inserts carried the uvrA1 coding sequence. Examination of restriction maps generated electronically from the genome sequence identified an 18-kbp overlap. Purified restriction fragments derived from the region of this overlap were used to locate irrE. It was determined that these fragments, some as small as 970 bp, could be used to successfully transform IRS24 to radioresistance and in so doing rapidly identify the region of the genome carrying the mutation. The irrE gene was localized to a coding sequence designated DR0167 in the TIGR Comprehensive Microbial Resource database (27). The irrE gene encodes a 35-kDa protein of unknown function, which, at present, appears to be unique to D. radiodurans. A search for sequence similarity between IrrE and other proteins suggests that IrrE may have an associated protease activity, but there is no experimental verification of this prediction.

Unlike its parent strain, the double mutant IRS24 (uvrA1 irrE1) is sensitive to ionizing radiation and UV light (Fig. 1 and 2). To determine if the observed sensitivity was solely due to the loss of the irrE gene product, the irrE coding sequence was disrupted in the R1 strain by using a transposon specifically designed for use in D. radiodurans (10). The resulting strain exhibited sensitivity to UV and ionizing radiation and could not grow in the presence of 60 ng of mitomycin C per ml, confirming that loss of IrrE alone was responsible for the sensitive phenotypes.

With regard to IrrE function, three possibilities seem likely: (i) IrrE is a novel DNA repair protein that recognizes a broad range of DNA damage; (ii) IrrE is an accessory protein that does not specifically interact with DNA damage, but is necessary to complete multiple repair processes; or (iii) IrrE is a regulatory protein that controls expression of proteins critical to DNA damage recognition and repair. We consider the first two alternatives unlikely, because our attempts to search existing databases with the IrrE sequence failed to connect this protein to any sequence motif associated with proteins that mediate DNA damage tolerance. Furthermore, studies of UV-induced DNA damage in this species revealed no evidence supporting the existence of a novel DNA repair protein. D. radiodurans has two excision repair pathways that target UV-induced DNA damage, UvrABC-mediated nucleotide excision repair (NER) and alternative excision repair (AER), which uses a UV damage endonuclease (11, 12, 22). Inactivation of both repair pathways is sufficient to sensitize D. radiodurans to UV radiation, and a D. radiodurans R1 uvrA uvs double mutant is as sensitive to UV light as LSU2030 (10). If IrrE targeted UV-induced DNA damage in a manner analogous to that of the proteins that mediate NER and AER, LSU2030 should be UV resistant, with the redundant activity of the NER and AER repair pathways protecting the cell.

We believe our results favor the third possibility. Relative gene expression values obtained with probes specific for the deinococcal recA (DR2340) indicate that IrrE influences recA expression following the culture's exposure to 3,000 Gy of gamma radiation. In R1 cells, this exposure leads to a 12.6-fold induction of recA transcript relative to unirradiated cultures. In LSU2030 cultures, this induction is only 2.6-fold, indicating that IrrE is a positive effector that must be present to maximally increase recA expression following administration of ionizing radiation. This result suggests that unusual regulatory circuitry is associated with recA expression in this species, reiterating the conclusion of Narumi et al. (26) that the D. radiodurans recA gene is controlled by a novel DNA damage response regulator.

Narumi et al. have reported that exposure to 2,000 Gy of gamma radiation will increase intracellular concentrations of D. radiodurans RecA approximately 2.5-fold relative to untreated cells (26). Even though this increase in RecA coincided with a 2.7-fold reduction in the deinococcal LexA protein, these authors found no evidence that LexA protein regulates transcription of recA in this species. Mutations that completely block lexA expression had no effect on recA expression, deviating from the SOS regulatory paradigm most commonly associated with recA expression. In other respects, the deinococcal LexA behaves much like LexA in E. coli. The D. radiodurans LexA undergoes autocatalytic cleavage into two fragments when incubated at elevated pH or when exposed to activated RecA. From the work of Narumi et al., it is apparent that deinococcal recA expression is limited by unknown factors in D. radiodurans. We believe IrrE is one of these factors.

At present, we cannot say with certainty that the inability of LSU2030 cultures to increase RecA levels in response to DNA damage is the reason for this strain's sensitivity to that damage, but it is not difficult to develop an argument supporting this possibility. We know that recA strains of D. radiodurans are extremely sensitive to mitomycin C, ionizing radiation, and UV light (14, 21) and that deinococcal RecA levels increase in response to DNA damage (7, 26). It is also well established that protein synthesis is required for effective radioresistance in this species; the addition of chloramphenicol dramatically lowers cell survival postirradiation (8, 9, 15, 16). Perhaps by limiting the amount of RecA synthesized, the level of DNA damage exceeds the cell's capacity to repair that damage quickly enough to avoid deleterious consequences. Alternatively, the reduction of recA expression may have a negligible effect on DNA damage tolerance. IrrE could up-regulate other genes, and the failure to transcribe these genes in LSU2030 is responsible for the increased sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents. Only further study will permit us to distinguish between these alternatives.

Acknowledgments

J.R.B. is supported by Department of Energy grant DE-FG02-01ER63151. Work by I.S.M. was supported by the Director, Office of Energy Reseach, Office of Health and Environmental Research, Division of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract no. DE-AC03-76F00098.

We gratefully acknowledge F. A. Rainey and M. A. Batzer and their laboratories at Louisiana State University for their assistance in DNA sequencing and quantitative real-time PCR, respectively. We thank Mie-Jung Park for assistance and helpful discussions of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, A. W., H. C. Nordon, R. F. Cain, G. Parrish, and D. Duggan. 1956. Studies on a radio-resistant micrococcus. I. Isolation, morphology, cultural characteristics, and resistance to gamma radiation. Food Technol. 10:575-578. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1995. Short protocols in molecular biology, 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

- 3.Battista, J. R. 1997. Against all odds: the survival strategies of Deinococcus radiodurans. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51:203-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battista, J. R. 2000. Radiation resistance: the fragments that remain. Curr. Biol. 10:R204-R205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Battista, J. R., A. M. Earl, and M. J. Park. 1999. Why is Deinococcus radiodurans so resistant to ionizing radiation? Trends Microbiol. 7:362-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burrell, A. D., P. Feldschreiber, and C. J. Dean. 1971. DNA membrane association and the repair of double breaks in X-irradiated Micrococcus radiodurans. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 247:38-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll, J. D., M. J. Daly, and K. W. Minton. 1996. Expression of recA in Deinococcus radiodurans. J. Bacteriol. 178:130-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean, C. J., P. Feldschreiber, and J. T. Lett. 1966. Repair of X-ray damage to the deoxyribonucleic acid in Micrococcus radiodurans. Nature 209:49-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean, C. J., J. G. Little, and R. W. Serianni. 1970. The control of post irradiation DNA breakdown in Micrococcus radiodurans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 39:126-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Earl, A. M., S. K. Rankin, K. P. Kim, O. N. Lamendola, and J. R. Battista. 2002. Genetic evidence that the uvsE gene product of Deinococcus radiodurans R1 is a UV damage endonuclease. J. Bacteriol. 184:1003-1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans, D. M., and B. E. Moseley. 1985. Identification and initial characterisation of a pyrimidine dimer UV endonuclease (UV endonuclease beta) from Deinococcus radiodurans; a DNA-repair enzyme that requires manganese ions. Mutat. Res. 145:119-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans, D. M., and B. E. Moseley. 1983. Roles of the uvsC, uvsD, uvsE, and mtcA genes in the two pyrimidine dimer excision repair pathways of Deinococcus radiodurans. J. Bacteriol. 156:576-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimsley, J. K., C. I. Masters, E. P. Clark, and K. W. Minton. 1991. Analysis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of DNA double-strand breakage and repair in Deinococcus radiodurans and a radiosensitive mutant. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 60:613-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutman, P. D., J. D. Carroll, C. I. Masters, and K. W. Minton. 1994. Sequencing, targeted mutagenesis and expression of a recA gene required for extreme radioresistance of Deinococcus radiodurans. Gene 141:31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hariharan, P. V., and P. A. Cerutti. 1972. Formation and repair of γ-ray-induced thymine damage in Micrococcus radiodurans. J. Mol. Biol. 66:65-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitayama, S., and A. Matsuyama. 1971. Double-strand scissions in DNA of gamma-irradiated Micrococcus radiodurans and their repair during postirradiation incubation. Agric. Biol. Chem. 35:644-652. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makarova, K. S., L. Aravind, Y. I. Wolf, R. L. Tatusov, K. W. Minton, E. V. Koonin, and M. J. Daly. 2001. Genome of the extremely radiation-resistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans viewed from the perspective of comparative genomics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:44-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattimore, V., and J. R. Battista. 1996. Radioresistance of Deinococcus radiodurans: functions necessary to survive ionizing radiation are also necessary to survive prolonged desiccation. J. Bacteriol. 178:633-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mattimore, V., K. S. Udupa, G. A. Berne, and J. R. Battista. 1995. Genetic characterization of forty ionizing radiation-sensitive strains of Deinococcus radiodurans: linkage information from transformation. J. Bacteriol. 177:5232-5237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minton, K. W. 1994. DNA repair in the extremely radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. Mol. Microbiol. 13:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moseley, B. E., and H. J. Copland. 1975. Isolation and properties of a recombination-deficient mutant of Micrococcus radiodurans. J. Bacteriol. 121:422-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moseley, B. E., and D. M. Evans. 1983. Isolation and properties of strains of Micrococcus (Deinococcus) radiodurans unable to excise ultraviolet light-induced pyrimidine dimers from DNA: evidence for two excision pathways. J. Gen. Microbiol. 129:2437-2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moseley, B. E., and A. Mattingly. 1971. Repair of irradiation transforming deoxyribonucleic acid in wild type and a radiation-sensitive mutant of Micrococcus radiodurans. J. Bacteriol. 105:976-983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moseley, B. E. B. 1983. Photobiology and radiobiology of Micrococcus (Deinococcus) radiodurans. Photochem. Photobiol. Rev. 7:223-275. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narumi, I., K. Cherdchu, S. Kitayama, and H. Watanabe. 1997. The Deinococcus radiodurans uvrA gene: identification of mutation sites in two mitomycin-sensitive strains and the first discovery of insertion sequence element from deinobacteria. Gene 198:115-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narumi, I., K. Satoh, M. Kikuchi, T. Funayama, T. Yanagisawa, Y. Kobayashi, H. Watanabe, and K. Yamamoto. 2001. The LexA protein from Deinococcus radiodurans is not involved in RecA induction following gamma irradiation. J. Bacteriol. 183:6951-6956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson, J. D., L. A. Umayam, T. Dickinson, E. K. Hickey, and O. White. 2001. The comprehensive microbial resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:123-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tigari, S., and B. E. B. Moseley. 1980. Transformation in Micrococcus radiodurans: measurement of various parameters and evidence for multiple, independently segregating genomes per cell. J. Gen. Microbiol. 119:287-296. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Udupa, K. S., P. A. O'Cain, V. Mattimore, and J. R. Battista. 1994. Novel ionizing radiation-sensitive mutants of Deinococcus radiodurans. J. Bacteriol. 176:7439-7446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White, O., J. A. Eisen, J. F. Heidelberg, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, M. L. Gwinn, W. C. Nelson, D. L. Richardson, K. S. Moffat, H. Qin, L. Jiang, W. Pamphile, M. Crosby, M. Shen, J. J. Vamathevan, P. Lam, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, C. Zalewski, K. S. Makarova, L. Aravind, M. J. Daly, K. W. Minton, R. D. Fleischmann, K. A. Ketchum, K. E. Nelson, S. Salzberg, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 1999. Genome sequence of the radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans R1. Science 286:1571-1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]