Abstract

Upon recognition of viral infection, RIG-I and Helicard recruit a newly identified adapter termed Cardif, which induces type I interferon (IFN)-mediated antiviral responses through an unknown mechanism. Here, we demonstrate that TRAF3, like Cardif, is required for type I interferon production in response to intracellular double-stranded RNA. Cardif-mediated IFNα induction occurs through a direct interaction between the TRAF domain of TRAF3 and a TRAF-interaction motif (TIM) within Cardif. Interestingly, while the entire N-terminus of TRAF3 was functionally interchangeable with that of TRAF5, the TRAF domain of TRAF3 was not. Our data suggest that this distinction is due to an inability of the TRAF domain of TRAF5 to bind the TIM of Cardif. Finally, we show that preventing association of TRAF3 with this TIM by mutating two critical amino acids in the TRAF domain also abolishes TRAF3-dependent IFN production following viral infection. Thus, our findings suggest that the direct and specific interaction between the TRAF domain of TRAF3 and the TIM of Cardif is required for optimal Cardif-mediated antiviral responses.

Keywords: Cardif, TRAF-interacting motif, TRAF3, type I interferon, virus

Introduction

Mammalian cells respond to viral infection by producing and secreting a family of cytokines called type I interferons (IFNs), composed of at least 13 IFNαs and a single IFNβ. These cytokines are recognized in an autocrine and paracrine manner by the IFNα/β receptor (IFNAR), thereby inducing the expression of numerous proteins that establish a cellular environment that is highly resistant to viral infection. As a result, type I IFNs comprise an extremely potent and critical component of the innate immune response against viral pathogens (Theofilopoulos et al, 2005).

There has been rapid progress in recent years toward furthering our understanding of how mammalian cells initially recognize the presence of a virus. Cells of the innate immune system, including macrophages and dendritic cells, utilize Toll-like receptors (TLRs) to detect and respond to viral infection (Bowie and Haga, 2005). In contrast, fibroblasts, which do not express TLRs, recognize intracellular double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) produced during viral infection through CARD-domain containing RNA helicases such as Helicard/MDA-5 and RIG-I (Andrejeva et al, 2004; Yoneyama et al, 2004, 2005; Kato et al, 2005). These ‘intracellular receptors' utilize a newly identified CARD-containing adapter called Cardif/IPS-1/MAVS/VISA to activate downstream signaling pathways (Kawai et al, 2005; Meylan et al, 2005; Seth et al, 2005; Xu et al, 2005). Interestingly, Cardif contains multiple TNF receptor-associated factor (TRAF)-interacting motifs (TIMs), suggesting that Cardif may induce antiviral responses through one or more members of the TRAF family (Xu et al, 2005).

Recently we identified TRAF3 as a critical molecule required for the induction of type I IFNs, but not inflammatory cytokines in response to viral infection and TLR ligation in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs), plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), and murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (Hacker et al, 2006; Oganesyan et al, 2006). Accordingly, TRAF3 was specifically required for the activation of IRF3, the transcription factor responsible for type I IFN upregulation, but not NF-κB, which coordinates the transcription of inflammatory cytokines. This finding distinguishes TRAF3 from all other known TRAFs, which predominantly act either as inhibitors or activators of NF-κB.

Despite these findings, it remains unclear how Cardif and TRAF3 are involved in the regulation of type I IFNs. In this report, we show that Cardif induces IFNα through a direct and specific interaction with the TRAF domain of TRAF3, implicating Cardif as the link between cytoplasmic viral receptors and TRAF3.

Results

TRAF3 is required for IFNα production in response to intracellular dsRNA

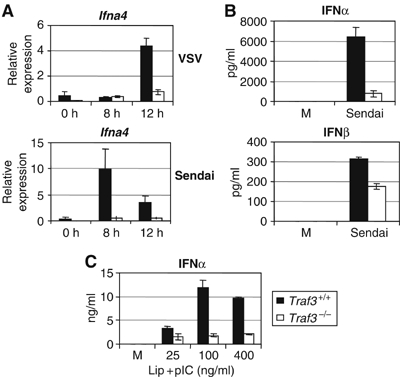

We previously found that TRAF3-deficient cells were susceptible to vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) infection resulting from a defective type I IFN response to this particular virus (Oganesyan et al, 2006). To examine whether TRAF3 is specifically involved in the recognition of VSV or may be more broadly involved in recognition of RNA viruses, we determined the ability of Traf3+/+ and Traf3−/− MEFs to induce IFNα in response to infection with both Sendai virus and VSV. Upregulation of Ifna4 mRNA was almost completely defective in Traf3−/− MEFs compared to wild-type cells (Figure 1A). Similarly, TRAF3-deficient cells secreted lower levels of IFNα and IFNβ 12 h after Sendai virus infection (Figure 1B). It is thought that dsRNA produced in the cytoplasm of fibroblasts during viral replication is detected by RNA-binding proteins responsible for transducing the cellular response to viral infection. We therefore tested whether TRAF3 could be involved in signal transduction pathways activated by the presence of intracellular dsRNA by transfecting wild-type and Traf3−/− MEFs with polyI:C, a synthetic form of dsRNA. When directly transfected into these cells, we found that polyI:C failed to induce a strong IFNα response in fibroblasts that lack TRAF3, indicating that TRAF3 is indeed required for innate antiviral responses to intracellular dsRNA (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

TRAF3 is required for IFNα production in response to intracellular dsRNA. (A) mRNA from Traf3 WT and KO MEFs was assayed for levels of Ifna4 following infection with Sendai or VSV by Q-PCR. (B) Supernatants from Traf3 WT and KO MEFs 12 h after infection with Sendai were analyzed for levels of IFNα and IFNβ by ELISA. (C) IFNα levels in culture supernatants 12 h following liposomal transfection of poly I:C were measured by ELISA.

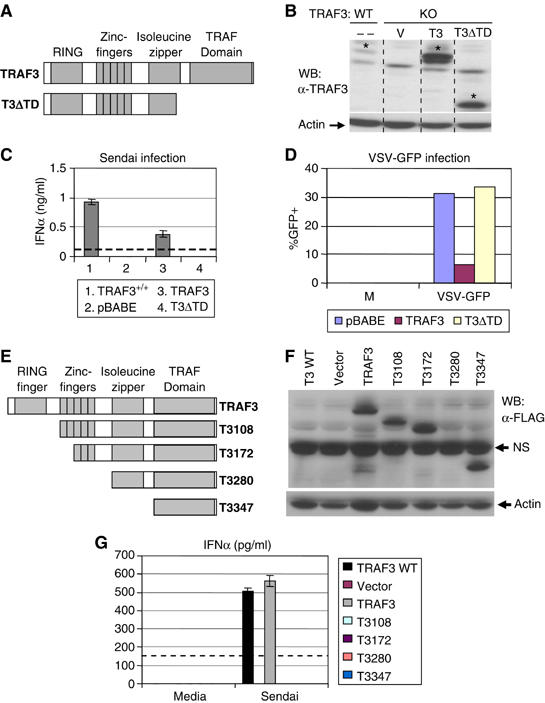

A structurally intact TRAF3 molecule is required for antiviral activity

Despite these findings, the molecular mechanisms by which TRAF3 is involved in viral response pathways remain unclear. To identify the minimal region required for TRAF3-mediated IFNα production, we reconstituted early passage Traf3−/− MEFs with a panel of truncation mutants of TRAF3 from the N- and C-terminus (Figure 2A, B, E and F). Transduced cells were then selected with puromycin and infected with VSV or Sendai virus. As shown in Figure 2C, Traf3−/− MEFs reconstituted with a TRAF3 truncation mutant lacking the TRAF domain could not rescue TRAF3-mediated IFNα production. Furthermore, when infected with a form of VSV that expresses GFP, MEFs reconstituted with a truncation mutant of TRAF3 lacking the TRAF domain exhibited similar levels of GFP+ cells as Traf3−/− MEFs reconstituted with vector alone (Figure 2D). We also found that Traf3−/− cells reconstituted with successive TRAF3 N-terminal truncation mutants failed to secrete IFNα following Sendai virus infection (Figure 2G). These data indicated that a structurally intact TRAF3 molecule is required for optimal type I IFN-mediated antiviral responses. However, the structural components of TRAF3 that were responsible for its unique biological role in mediating antiviral responses remained unclear.

Figure 2.

A structurally intact TRAF3 molecule is required for antiviral activity. (A, E) Traf3−/− MEFs were reconstituted with the indicated constructs. (B, F) Expression was monitored by immunoblotting. (C, G) Reconstituted cells were then infected with Sendai virus for 24 h and IFNα levels in the supernatants were assayed by ELISA. (D) Cells from (B) were infected with VSV-GFP. VSV replication was monitored by flow cytometry. NS designates a nonspecific band. Dotted line indicates the limit of detection for the IFNα ELISA.

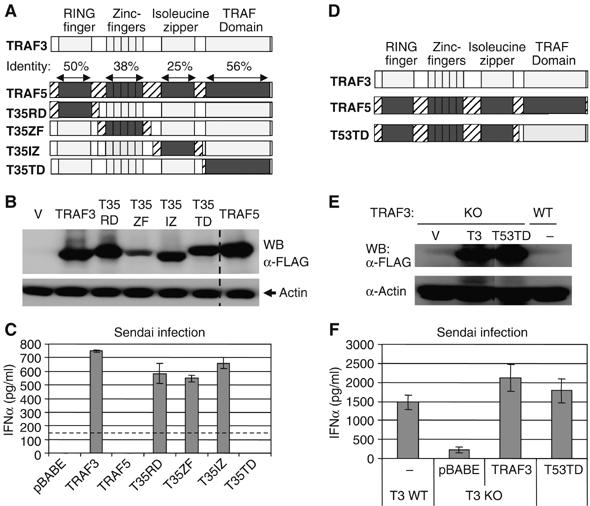

The TRAF domain of TRAF3 is specifically required for TRAF3-mediated type I IFN production

The secondary structure of TRAF3 is nearly identical to that of TRAF5 (Figure 3A). Nevertheless, TRAF5 could not functionally replace TRAF3 in our reconstitution system (Figure 3C). Therefore, the functional role of TRAF3 appears to be mediated by unique characteristics of its primary amino-acid sequence. To determine which structural features grant TRAF3 its unique function, we generated TRAF3/TRAF5 chimeras in which each of the domains of TRAF3 were replaced with those of TRAF5 (Figure 3A). Traf3−/− MEFs were then reconstituted with these chimeric molecules and infected with Sendai virus (Figure 3B). Surprisingly, the TRAF3 chimeras containing the RING domain, zinc-fingers, or isoleucine zipper of TRAF5 fully reconstituted TRAF3-dependent IFNα production. In contrast, MEFs expressing the TRAF domain chimera completely failed to reconstitute this function (Figure 3C), suggesting that the TRAF domain is responsible for the functional distinction between these two molecules. To further test whether the TRAF domain of TRAF3 allows for its unique functional role in antiviral responses, we reconstituted Traf3−/− MEFs with a chimeric molecule in which the entire N-terminus of TRAF5 is fused to the TRAF domain of TRAF3 (Figure 3D and E). As shown in Figure 3F, this chimeric molecule almost completely reconstituted TRAF3-mediated IFNα production. Thus, the TRAF domain but not the RING domain, zinc-fingers, or isoleucine zipper of TRAF3 is responsible for its unique role in mediating the cellular antiviral response.

Figure 3.

The TRAF domain of TRAF3 is specifically required for TRAF3-mediated type I IFN production. (A, B, D, E) Traf3−/− MEFs were reconstituted as in Figure 2 with the indicated TRAF3/TRAF5 chimeric molecules and expression was monitored by immunoblotting. (C, F) IFNα production by reconstituted cells 24 h following Sendai infection was monitored by ELISA. Dotted line indicates the limit of detection for the IFNα ELISA.

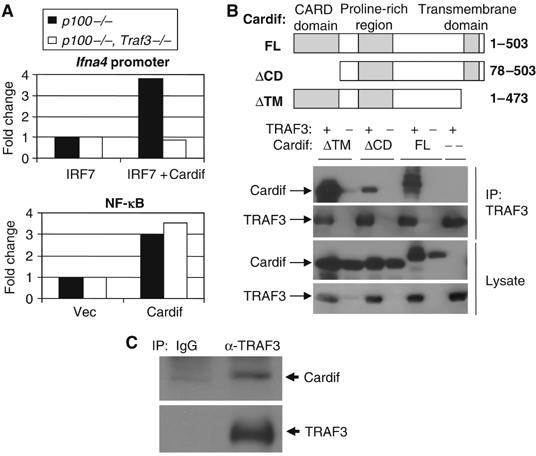

Cardif activates IFNα response through TRAF3

These findings suggested that the TRAF domain of TRAF3, but not that of TRAF5, is capable of forming a critical interaction in the type I IFN pathway. Cardif was recently identified as an essential adapter for cytoplasmic dsRNA receptors such as RIG-I and Helicard (Kawai et al, 2005; Meylan et al, 2005; Seth et al, 2005; Xu et al, 2005). Interestingly, Cardif contains a well-conserved TRAF-interacting motif (TIM) within its proline-rich region (PRR), which may be capable of forming specific interactions with the TRAF domain of TRAF3 (Xu et al, 2005). To assess whether TRAF3 is involved in Cardif-mediated induction of type I IFN, we transfected Traf3−/− and Traf3+/+ MEFs with IFN regulatory factor 7 (IRF7) and Cardif, together with an Ifna4 or NF-κB reporter construct. TRAF3-deficient cells have basally high activity of the NF-κB p100 subunit (He et al, manuscript in preparation). To control for any effect of this activity in our luciferase assays, a p100−/− background was used. As shown in Figure 4A, Cardif-mediated Ifna4 induction was completely dependent on TRAF3. In contrast, Cardif-mediated activation of an NF-κB luciferase reporter was similar in both Traf3+/+ and Traf3−/− MEFs.

Figure 4.

Cardif activates IFNα response through TRAF3. (A) p100−/−, Traf3+/+ MEFs or p100−/−, Traf3−/− MEFs were transiently transfected with an NF-κB or Ifna4 reporter, IRF7, and either Cardif or vector control. Luciferase activity was measured 24–48 h later. (B) TRAF3 associates with Cardif independently of the CARD domain and transmembrane region of Cardif when coexpressed in 293T cells by immunoprecipitation assay. 293T cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and immunoprecipitated using αTRAF3 antibodies. (C) Endogenous association of TRAF3 and Cardif. Whole-cell lysates from ∼20 million NIH 3T3 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation assay using αTRAF3 or isotype control antibodies, followed by immunoblotting for the presence of Cardif or TRAF3.

We next sought to determine whether TRAF3 and Cardif interact. Indeed, Cardif associated with TRAF3 in a manner that was independent of its CARD domain and transmembrane region when overexpressed in 293T cells (Figure 4B). Furthermore, constitutive association of TRAF3 and Cardif was also observed at endogenous levels (Figure 4C). Thus, TRAF3 and Cardif may form a complex involved in the regulation of type I IFNs.

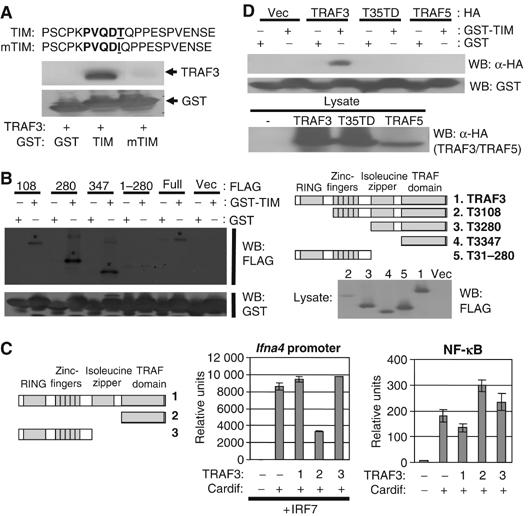

A TIM found within the proline-rich region of Cardif specifically interacts with the TRAF domain of TRAF3

As mentioned above, Cardif contains a well-conserved TIM sequence within its proline-rich region (PRR). To examine whether this TIM could associate with TRAF3, we constructed GST fusion proteins with a 21-amino-acid stretch from the PRR of Cardif containing either the wild-type TIM sequence or one containing a single conserved amino-acid mutation. We then subjected TRAF3 to a GST pull-down assay using these fusion proteins. As demonstrated in Figure 5A, TRAF3 strongly associated with the wild-type but not the mutated TIM of Cardif. Typically, TIMs interact with TRAF molecules through a direct association with the TRAF domain. Upon investigation of the region of TRAF3 involved in this interaction, we found that the TRAF domain was both necessary and sufficient to associate with the TIM of Cardif (Figure 5B). Therefore, these experiments established the ability of this region of Cardif to act as a classic TIM by binding the TRAF domain of TRAF3.

Figure 5.

A TIM found within the proline-rich region of Cardif specifically interacts with the TRAF domain of TRAF3. (A) TRAF3 associates with the TIM of Cardif. TRAF3 was subjected to a GST pulldown assay using GST alone or GST fused to the indicated amino-acid sequences as bait. (B) TRAF3 associates with the TIM of Cardif through its TRAF domain. The indicated truncation mutants of TRAF3 were subjected to a GST pulldown assay using GST alone or GST-TIM as bait. (C) The TRAF domain of TRAF3 specifically abrogates Cardif-mediated activation of Ifna4 promoter. 293T cells were transfected with the indicated constructs at an equal ratio of Cardif to TRAF3 or TRAF3 mutant plasmids and luciferase activity was measured after 24–48 h. (D) The TRAF domain of TRAF3 but not that of TRAF5 interacts with the TIM of Cardif. The indicated TRAF constructs were subjected to GST pulldown assays as above.

Despite the ability of the TRAF3 TRAF domain to bind the TIM of Cardif, it could not rescue TRAF3-mediated antiviral type I IFN production (Figure 2G). As it lacks any other required functional domains, we wanted to test whether the TRAF domain of TRAF3 would have any dominant negative effect on Cardif-mediated signaling. 293T cells were cotransfected with Cardif, IRF7, and an Ifna4 promoter or NF-κB luciferase construct along with wild-type TRAF3, the TRAF domain of TRAF3 alone, or an N-terminal segment of TRAF3 as a control. As shown in Figure 5C, coexpression of the TRAF domain of TRAF3, but not wild-type TRAF3 or the TRAF3 N-terminus, significantly abrogated Cardif-mediated activation of the Ifna4 promoter. In contrast, the TRAF domain of TRAF3 did not impede Cardif-mediated activation of the NF-κB luciferase construct (Figure 5C). Thus, the TRAF domain of TRAF3 is sufficient to bind Cardif and specifically inhibit its ability to activate the Ifna4 promoter. This suggests that the TRAF domain of TRAF3 may act as a dominant negative in blocking Cardif-mediated induction of type I IFNs by blocking the ability of Cardif to bind and recruit wild-type TRAF3.

Interestingly, our reconstitution experiments showed that the TRAF domain of TRAF3 is responsible for the functional difference between TRAF3 and TRAF5 in regulating antiviral responses (Figure 3). This result implied that the TRAF3 TRAF domain may mediate specific interactions required for the induction of type I IFNs. To determine if the functional distinction between the TRAF domains of TRAF3 and TRAF5 may be due to a differential affinity for the TIM in Cardif, we subjected wild-type TRAF3, wild-type TRAF5, and our TRAF domain chimera to a GST pull-down assay using the GST-TIM fusion protein as bait. As shown in Figure 5D, the TRAF domain of TRAF3, but not that of TRAF5, specifically bound the TIM of Cardif. Thus, TRAF3 may be specificity recruited to viral detection pathways via a direct and specific interaction with the TIM of Cardif.

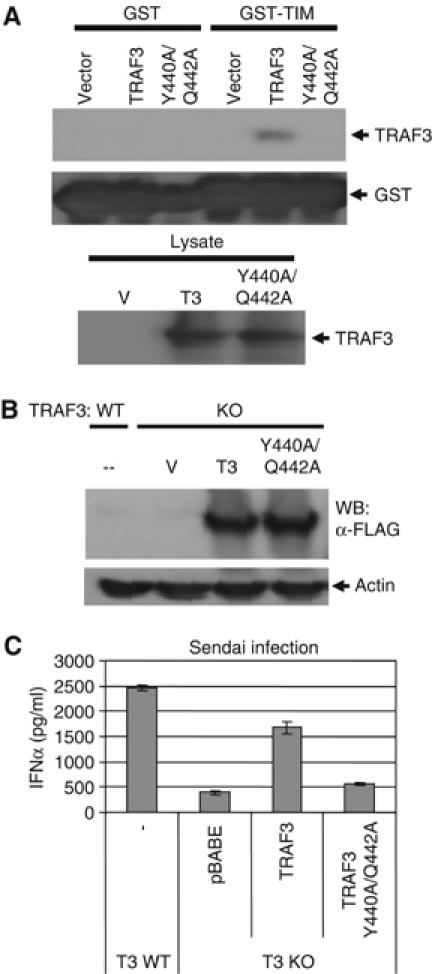

Mutation of the TIM-binding pocket in TRAF3 abolishes the IFNα response to Sendai virus

The above experiments demonstrated that the TIM of Cardif specifically bound the TRAF domain of TRAF3. However, we next wanted to test whether the ability of TRAF3 to bind the TIM of Cardif was actually required for type I IFN production under more physiological conditions. A previous report identified two critical amino acids, Y440 and Q442, in the interaction between TRAF3 and a similar TIM through crystal structure analysis (Ni et al, 2004). To confirm the importance of these two amino acids in Cardif-mediated signaling, we created a mutant form of TRAF3 in which both amino acids were mutated to alanine and tested whether this mutant form of TRAF3 could bind the Cardif-TIM. As expected, the Y440A/Q442A TRAF3 mutant had dramatically reduced affinity for the Cardif-TIM as demonstrated by GST pull-down assay (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Mutation of the TIM-binding pocket in TRAF3 abolishes the IFNα response to Sendai virus. (A) The Y440A/Q442A TRAF3 mutant no longer binds the Cardif-TIM. The indicated constructs were subjected to GST pull-down assay as above using GST alone or the Cardif-TIM fused to GST as bait. (B) Traf3−/− MEFs were reconstituted with wild-type Traf3 or the double point mutant of Traf3, which abolishes its ability to bind the Cardif-TIM. Expression was monitored by immunoblot. (C) IFNα production by reconstituted cells 24 h following Sendai infection was monitored by ELISA.

This mutant form of TRAF3 then allowed us to test whether the specific interaction between the TIM of Cardif and the TRAF domain of TRAF3 was functionally significant. Traf3−/− MEFs were reconstituted with vector alone, wild-type TRAF3, or the Y440A/Q442A TRAF3 mutant and infected with Sendai virus (Figure 6B). As shown in Figure 6C, mutation of the TIM-binding pocket almost completely abolished TRAF3-mediated IFNα production in response to Sendai infection. Thus, the ability of TRAF3 to interact with a TIM, such as that found within Cardif, plays a critical role in the antiviral response.

Discussion

The mammalian genome encodes multiple mechanisms for the detection of viral infection. In macrophages, dsRNA is recognized by TLR3 which utilizes the adapter TRIF to induce type I IFNs, thereby inhibiting viral replication. In plasmacytoid dendritic cells, the most potent producers of type I IFNs, ssRNA and unmethylated DNA are recognized by TLRs 7/8 and 9, respectively. In fibroblasts, which do not express TLRs, dsRNA within the cytoplasm is detected through CARD-containing RNA helicases such as Helicard and RIG-I. Thus, type I IFNs can be upregulated by multiple TLR-dependent and TLR-independent pathways (Kawai and Akira, 2006). Nevertheless, in all of the aforementioned cases, we have now shown that TRAF3 is specifically required for induction of the type I IFN-dependent antiviral response, establishing this adapter as a major convergence point for multiple recognition pathways as well as a key molecular mediator of host defense mechanisms against viral infection (Oganesyan et al, 2006).

Cardif was originally identified as a protein capable of activating the NF-κB and type I IFN pathways when overexpressed. Recent studies indicate that Cardif is, in fact, required for downstream signaling by Helicard and RIG-I via homotypic interactions between their CARD domains. The RNA helicase domain of RIG-I or Helicard most likely acts as an inhibitory domain that is released upon recognition of dsRNA. This recognition event then allows the CARD domains of Helicard/RIG-I to recruit and bind the Cardif CARD domain (Kawai et al, 2005; Meylan et al, 2005; Seth et al, 2005; Xu et al, 2005). Although one study by Xu et al (2005) suggested that Cardif activates NF-κB through TRAF6, how Cardif induces type I IFN-mediated antiviral responses was not known. Our study resolves this remaining question by showing that Cardif utilizes TRAF3 to activate type I IFN production through a direct interaction by virtue of its well-conserved TIM.

It is interesting to note that Cardif most likely activates NF-κB through TRAF6 while regulating IRF transcription factors through TRAF3 (Xu et al, 2005). Indeed, Cardif contains multiple TIMs, some of which would interact preferentially with TRAF3 and others that would interact preferentially with TRAF6. In fact, by reconstituting TRAF3-deficient cells with its close homologue TRAF5, which is a potent activator of NF-κB, we can highlight the specific function of TRAF3. Traf3−/− fibroblasts expressing TRAF5 failed to produce IFNα in response to Sendai virus infection compared to Traf3−/− cells reconstituted with TRAF3. Through the reconstitution of Traf3−/− cells with a series of chimeric molecules between TRAF3 and TRAF5, we further mapped the TRAF domain as the region responsible for the functional difference between these closely related proteins. This is consistent with our observation that only the TRAF domain of TRAF3 but not that of TRAF5 can bind to the TIM of Cardif.

TRAF molecules are at the center of numerous immunological and physiological processes. Although highly homologous, our results suggest that relatively minor structural differences between TRAF family members can have dramatic functional consequences due to highly specific interactions with other signaling molecules. It is now evident that these distinctions between TRAF family members can make the difference between a general inflammatory response and a specific type I IFN-mediated antiviral response. Further analysis into the mechanistic and structural differences between TRAF family members may eventually allow us to guide the immunological response in a manner that more appropriately targets a specific pathogen.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Poly I:C was purchased from Amersham Biosciences AB (Uppsala, Sweden). Anti-HA and anti-TRAF3 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-Myc antibody was obtained from Cell Signalling Technologies (Beverly, MA). Anti-actin antibody was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Anti-Cardif antibodies were obtained from Axxora (San Diego, CA). M2 monoclonal antibody was used to detect Flag-tagged molecules. IFNα and IFNβ ELISA reagents were obtained from PBL Biomedical Laboratories (Piscataway, NJ). IFNα ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer's recommended protocols. VSV expressing GFP and Sendai virus (SeV; Z strain) were kind gifts from Dr Glen Barber and Dr Debi Nayak, respectively. Lipofectamine reagent was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Luciferase assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). Rabbit TrueBlot beads and secondary antibodies were obtained from eBioscience (San Diego, CA).

Constructs

An MGC clone (ID 4190175) containing the full sequence of Cardif was obtained from Invitrogen and sequenced to verify integrity of the insert. Myc-tagged full-length, ΔTM, and ΔCARD Cardif were generated by PCR using the MGC clone as a template and inserted into pcDNA3.1-TOPO (Invitrogen). GST-TIM and GST-mTIM were constructed as previously described (Li et al, 2002). Briefly, synthetic DNA oligos corresponding to the 21-amino-acid region of Cardif containing the TIM or a single isoleucine mutant thereof were annealed and ligated into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pGEX-2T. All TRAF3 deletion mutants were PCR cloned into EcoRI/SalI into a pBABEpuro retroviral vector with an N-terminal Flag tag. TRAF3/TRAF5 chimeras were constructed using standard overlapping PCR techniques and cloned into pBABEpuro. Double point mutants of TRAF3 were constructed using a Quikchange kit (Stratagene) and wild-type TRAF3 in a pBABE-puromycin vector as a template.

Quantitative PCR

RNA was isolated and analyzed by real-time quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) as described previously (Doyle et al, 2002). Ifna4 primers were forward, CCTGTGTGATGCAGGAACC; reverse TCACCTCCCAGGCACAGA. All measurements are displayed as relative expression units after normalization to L32.

Cell culture

MEFs were isolated from day 15 embryos. MEFs and HEK 293T cells were cultured in 5% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) as described previously (Oganesyan et al, 2006).

Reconstitution

To reconstitute Traf3−/− cells, HEK 293T cells were transfected with a Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus ΨÃ-MLV helper construct plus pBABEpuro alone or pBABEpuro with the indicated construct using standard calcium phosphate methods. Traf3−/− MEFs were then infected with the filtered 293T cell supernatants followed by selection with 2.5 μg/ml of puromycin before infection with either Sendai virus or VSV.

Luciferase reporter assay

p100−/− and Traf3−/−, p100−/− cells were transfected via electroporation with pGL2-Basic containing the murine Ifna4 promoter or 2 × NF-κB-binding sites and the indicated constructs according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD). For 293T cell experiments, 293T cells were transfected with the indicated constructs using standard calcium phosphate methods. After 24–48 h, the cells were lysed and luciferase activity was determined using a luminometer. Measurements are displayed in relative light units (RLU) and are normalized to β-galactosidase levels in each sample.

Immunoprecipitation and GST pulldown assay

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments and the GST pulldown assays were performed as previously described (Cheng and Baltimore, 1996). In GST pulldowns, glutathione beads (Sigma Aldrich) were incubated with Escherichia coli-expressed GST-TIM, GST-mTIM, or GST alone for 2 h. Glutathione beads were then washed and incubated for 1.5 h with lysates of 293T cells expressing the indicated TRAF3 or TRAF5 constructs. After washing, protein was eluted from the beads and separated by SDS–PAGE. Immunoblotting was performed as described previously (Oganesyan et al, 2006). Endogenous immunoprecipitation was performed using Rabbit TrueBlot immunoprecipitation system according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wei Peng and Zihe Rao for their helpful discussions. G Oganesyan, A Shahangian, S Liu, and SK Saha are supported by the UCLA Medical Scientist Training Program training grant (GM 08042). EM Pietras is supported by the Ruth L Kirchstein National Research Service Award (GM 07185). JQ He is supported by the Clinical and Fundamental Immunology Training Grant (AI07126-30). Part of this work was also supported by National Institutes of Health research grants R01 AI056154 and 1R01 AI069120.

References

- Andrejeva J, Childs KS, Young DF, Carlos TS, Stock N, Goodbourn S, Randall RE (2004) The V proteins of paramyxoviruses bind the IFN-inducible RNA helicase, mda-5, and inhibit its activation of the IFN-beta promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 17264–17269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie AG, Haga IR (2005) The role of Toll-like receptors in the host response to viruses. Mol Immunol 42: 859–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G, Baltimore D (1996) TANK, a co-inducer with TRAF2 of TNF- and CD 40L-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Genes Dev 10: 963–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle S, Vaidya S, O'Connell R, Dadgostar H, Dempsey P, Wu T, Rao G, Sun R, Haberland M, Modlin R, Cheng G (2002) IRF3 mediates a TLR3/TLR4-specific antiviral gene program. Immunity 17: 251–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker H, Redecke V, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Hsu LC, Wang GG, Kamps MP, Raz E, Wagner H, Hacker G, Mann M, Karin M (2006) Specificity in Toll-like receptor signalling through distinct effector functions of TRAF3 and TRAF6. Nature 439: 204–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Uematsu S, Matsui K, Tsujimura T, Takeda K, Fujita T, Takeuchi O, Akira S (2005) Cell type-specific involvement of RIG-I in antiviral response. Immunity 23: 19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Akira S (2006) TLR signaling. Cell Death Differ 13: 816–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Takahashi K, Sato S, Coban C, Kumar H, Kato H, Ishii KJ, Takeuchi O, Akira S (2005) IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nat Immunol 6: 981–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Ni CZ, Havert ML, Cabezas E, He J, Kaiser D, Reed JC, Satterthwait AC, Cheng G, Ely KR (2002) Downstream regulator TANK binds to the CD40 recognition site on TRAF3. Structure 10: 403–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan E, Curran J, Hofmann K, Moradpour D, Binder M, Bartenschlager R, Tschopp J (2005) Cardif is an adaptor protein in the RIG-I antiviral pathway and is targeted by hepatitis C virus. Nature 437: 1167–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni CZ, Oganesyan G, Welsh K, Zhu X, Reed JC, Satterthwait AC, Cheng G, Ely KR (2004) Key molecular contacts promote recognition of the BAFF receptor by TNF receptor-associated factor 3: implications for intracellular signaling regulation. J Immunol 173: 7394–7400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oganesyan G, Saha SK, Guo B, He JQ, Shahangian A, Zarnegar B, Perry A, Cheng G (2006) Critical role of TRAF3 in the Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent antiviral response. Nature 439: 208–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth RB, Sun L, Ea CK, Chen ZJ (2005) Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-kappaB and IRF 3. Cell 122: 669–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theofilopoulos AN, Baccala R, Beutler B, Kono DH (2005) Type I interferons (alpha/beta) in immunity and autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol 23: 307–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu LG, Wang YY, Han KJ, Li LY, Zhai Z, Shu HB (2005) VISA is an adapter protein required for virus-triggered IFN-beta signaling. Mol Cell 19: 727–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama M, Kikuchi M, Matsumoto K, Imaizumi T, Miyagishi M, Taira K, Foy E, Loo YM, Gale M Jr, Akira S, Yonehara S, Kato A, Fujita T (2005) Shared and unique functions of the DExD/H-box helicases RIG-I, MDA5, and LGP2 in antiviral innate immunity. J Immunol 175: 2851–2858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama M, Kikuchi M, Natsukawa T, Shinobu N, Imaizumi T, Miyagishi M, Taira K, Akira S, Fujita T (2004) The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat Immunol 5: 730–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]