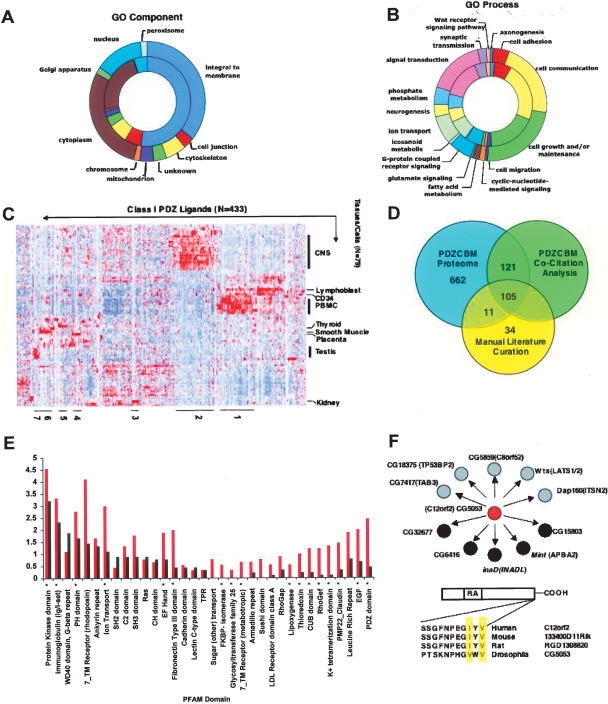

Figure 3.

Characteristics of the PDZCBM. Distribution of cellular component (A) and biological process (B) GO categories. (Inner rings) Proteins encoded by the literature ligands (174 with GO component and 172 with GO biological process identifiers); (outer rings) proteins encoded by the PDZCBM (728 with GO component and 733 with GO biological process identifiers). Each section represents the number of proteins assigned to a given GO category. Both the literature and the PDZCBM gene sets are significantly enriched for integral to membrane (P < 0.001). The distribution between GO biological process categories did not change between the literature and the PDZCBM gene set, with 12 out of the 16 categories enriched in both gene sets (P < 0.05, Fischer’s exact test-hypergeometric probability distribution using a background set of 13,802 GO annotated human genes). (C) Identification of neuronal and immune tissue expression modules in the PDZCBM gene set. For illustrative purposes, the mRNA expression patterns after hierarchical clustering of both tissue and genes are shown for 433 Class I members of the PDZCBM gene set (433 out of 505 Class I genes had probes meeting filtering criteria). Although there exists strong expression in smooth muscle and testes for several ligands, for instance, the profiles are dominated by the prominent clusters of ligands in neural and immune tissues, paralleling the expression of subsets of PDZ genes. Similar dominant immune and neural expression clusters were observed for Class II and III subsets. The identity of the individual PDZCBM constituents in the numbered tissue expression clusters can be found in Supplemental Table 3. (D) Assessment of previous experimentally confirmed PDZ ligands within the PDZCBM set versus potential novel ligands. The automated MILANO literature mining software package revealed that 219 of the 899 genes were co-cited (as of Jan. 15, 2006) with the term PDZ, with an additional 18 genes found to be co-cited by manual examination of PubMed. The 237 overlapped with 116 of the unique ligands in our manually curated literature PDZ–ligand interaction data set (Rubinstein and Simon 2005). Eleven out of 116 genes that are verified PDZ ligands with conserved canonical binding motifs were not found by the automated co-citation software to be linked to the term PDZ. An additional 34 genes with non-canonical binding motifs were identified by manual literature curation. In summary, there are 662 genes that have not been shown to bind to a PDZ protein or be co-cited with the term PDZ with conserved canonical PDZ-binding motifs. (E) Frequency distribution and enrichment of PFAM domains in the PDZCBM proteome. The PFAM database was used to identify domains for the reference protein sequence of each member of the 899 PDZCBM gene set. For illustrative purposes, PFAM domain frequency of the PDZCBM is shown compared with an equivalently sized random gene set. Domains marked with asterisks are significantly (P-value < 0.01, Fischer’s exact test) enriched across the entire PDZCBM proteome compared with the domain composition of the human proteome. (F) Interolog data of PDZ–ligand interactions. We identified Drosophila orthologs for the 29.9% (269/899) PDZCBM members. Of these Drosophila proteins, 31.6% (93/269) had conserved the mammalian PDZ-binding motif. We subsequently interrogated the large-scale Drosophila Y2H screen of Giot et al. (2003) for this subset of proteins looking for interactions with PDZ domain-containing proteins. For example, C12orf2 is an RA domain-containing protein whose fly ortholog, CG5053, was found to interact with four PDZ domain-encoding proteins (black circles) as well several other proteins (gray circles) with high confidence. Thus, comparative genomics coupled with annotation transfer strongly suggest that C12orf2 interacts with PDZ proteins.