Diagnostic assessment is a fundamental aspect of clinical care. It involves gathering key information to describe and understand the patient's clinical condition and to organize an effective care plan. The diagnostic model underlying the assessment enterprise should be consistent with up-to-date international standards and be as highly reliable and valid as possible. The actual diagnostic assessment should be conducted from the start with a clear therapeutic goal and tone, engaging the patient and family throughout the process.

The need to upgrade along these perspectives the quality of psychiatric diagnostic assessment across the world has led the WPA to organize and carry out since the mid 1990s a project towards the preparation of International Guidelines for Diagnostic Assessment (IGDA). This report briefly describes the background and development of this project, the content of its first product, i.e. the IGDA Essentials Booklet, and its future perspectives.

BACKGROUND

Clinical diagnosis involves knowledge, skills, and attitudes that demand the best of our scientific, humanistic and ethical talents and aspirations. The philosopher and historian of medicine Pedro Lain-Entralgo (1) cogently argues that diagnosis is more than just identifying a disorder (nosological diagnosis) and more than distinguishing one disorder from another (differential diagnosis); it is in fact understanding thoroughly what goes on in the mind and the body of the person who presents for care. Furthermore, this understanding must be contextualized within the history and the culture of each patient for it to be meaningful and helpful.

Recent advances in the methodology for psychiatric diagnosis have included a more systematic and reliable description of disorders and multiaxial schemas for addressing the frequent plurality of the patient's clinical problems and their biopsychosocial contextualization (2). On the other hand, compelling arguments have been made about the need to enhance the validity of these diagnostic formulations by attending to symbols and meanings that are pertinent to the identity and perspectives of the patients involved (3). Furthermore, in the increasingly multicultural world in which we live, it is essential to strive for an effective integration of universalism (that facilitates professional communication across centers and continents) and local realities and needs (which address the uniqueness of the patient in his/her particular context) (4).

Some of the roots of the WPA project on IGDA can be found in the dedicated collaboration between the World Health Organization (WHO) and the WPA, through its Executive Committee and its Section on Classification and Diagnostic Assessment, towards the development of the ICD-10. Additionally, the WPA Classification Section as such or some of its leaders assisted in the development of the DSM-IV, the recent Chinese classification of mental disorders (CCMD-2-R, CCMD-3), the Third Cuban Glossary of Psychiatry (GC- 3) and the Latin American Guide for Psychiatric Diagnosis. Relevant also to this project has been the work of the WPA Classification Section on international psychiatric classification and diagnosis, as reflected in two conferences over the past two decades, during which African, Chinese, Egyptian, French, Japanese, Latin American, North American, Russian, Scandinavian, and South Asian perspectives were discussed (5,6).

DEVELOPMENT OF THE IGDA PROJECT

The conceptualization and organization of the IGDA project has been, from beginning to present, an initiative of the WPA Section on Classification and Diagnostic Assessment. The idea of the project was a result of the International Survey on Diagnostic Assessment Procedures conducted by the Section in the early 1990s. The survey revealed a widely perceived need for more comprehensive diagnostic approaches, which were recommended to be culturally informed and generated in a truly international manner (7).

In consideration of this international survey, the Section on Classification and Diagnostic Assessment decided in 1994 to start the development of the IGDA project. The first meeting for this purpose took place in Kaufbeuren, Germany. Since then, meetings have been held in Canada, China, France, Germany, Mexico, India, Turkey, and the United States. The initial work group for this project has been composed of experts representing several theoretical approaches and fields of psychiatry. As a group, they cover all continents, consistent with the diversity of the Section membership. They include J.E. Mezzich (Chair), C.E. Berganza, M. von Cranach, M.R. Jorge, M.C. Kastrup, R. Srinivasa Murthy, A. Okasha, C. Pull, N. Sartorius, A. Skodol and M. Zaudig. In 1997, the WPA Executive Committee adopted the project as a WPA Educational Program. Later the project received central institutional funding to facilitate its progress.

CHARACTERISTICS AND COMPONENTS OF THE IGDA PROJECT

A central feature of the IGDA project involves the assessment of the psychiatric patient as a whole person, rather than just as a carrier of disease. Thus, it assumes in the clinician the exercise of scientific competence, humanistic concern, and ethical aspirations. Another essential feature is the coverage of all key areas of information (biological, psychological and social) pertinent to describing the patient's pathology, dysfunctions and problems as well as his/her positive aspects or assets. A third important feature involves basing the diagnostic assessment on the interactive engagement among the clinician, the patient, and his/her family, leading to a joint understanding of the patient's clinical condition and a joint assumption and monitoring of the treatment plan. Fourth, IGDA uses ICD-10 as a basic reference in general, and in particular for the first three axes of its multiaxial formulation (classification of mental and general medical disorders, disabilities, and contextual factors). Regional adaptations of ICD-10, such as DSM-IV, the Chinese CCMD-2-R, the Cuban GC-3, or the Latin American Guide for Psychiatric Diagnosis, may be used as well.

It is important to point out the need to employ, in the diagnostic assessment process, scientific objectivity and evidence-based procedures, as well as intuition and clinical wisdom, in order to enhance the descriptive validity and the therapeutic usefulness of the diagnostic formulation. Furthermore, it is critical for the effectiveness of the diagnostic enterprise to use a culturally informed framework, both for the development of updated diagnostic models and procedures as well as for the conduction of a competent clinical evaluation of every patient.

The main products of the IGDA project include the following:

An Essentials Booklet, presenting concisely the guidelines. This component has already been completed and is being published elsewhere. It is outlined in the next section.

An Educational Protocol, to organize various educational formats for the presentation of the guidelines to different audiences and settings, from a short lecture to an extended course.

A Bases Book, to provide literature reviews related to the development and content of the guidelines and to discuss their implications.

A Case Book, to present illustratively and heuristically the results of the application of the guidelines to diverse cases from across the world.

The IGDA Essentials Booklet

This booklet presents concisely the 100 IGDA guidelines, along with explanatory graphs and tables, and additional recommended readings. This material is organized into ten sections covering, broadly speaking, conceptual bases, interviewing and informational sources, symptom and supplementary assessments, comprehensive diagnostic formulation, treatment planning and chart organization.

These guidelines are offered as recommendations for both inpatient and outpatient care, and for both child and adult psychiatry. The manner of their application is expected to be informed by local realities and needs. The guidelines are presented in a deliberately compact form, deferring for the Bases Book a detailed presentation of their implications and adaptations to different clinical situations.

Section 1 offers a conceptual framework for the whole diagnostic process, including historical, cultural and clinical perspectives, definitions of core constructs and procedures, and their overall articulation for enhancing clinical care.

Section 2 focuses on patient interviewing. It is based on the establishment of optimal clinician-patient engagement aimed at systematic data gathering through a fluid process, maintaining a deliberate therapeutic tone. The interviewing process is organized into opening, body, and closure phases. Complementarily, Section 3 deals with the use of extended sources of information. It discusses the covering of key additional informational sources, such as relatives, friends, other living informants, and documentary sources. It also attends to the resolution of conflictual information and the protection of confidentiality.

Guidelines for the core characterization of a psychopathological case are the subject of Section 4. It organizes the assessment of major symptomatological areas and the key components of the mental status examination. Supplementary assessment procedures are reviewed in Section 5 (concerning psychopathological, neuropsychological and physical aspects) and Section 6 (concerning functioning, social context, cultural framework and quality of life).

One of the most innovative contributions of these guidelines involves a new comprehensive diagnostic model that articulates a standardized multiaxial evaluation with a personalized idiographic one. Personalized interventions call for personalized assessments. The corresponding recommendations concerning the conceptualization and formulation of a comprehensive diagnostic statement are the matter of Sections 7 and 8. Section 7 focuses on the standardized multiaxial formulation, involving clinical disorders, disabilities, contextual factors, and, as a new axis, quality of life. Section 8 deals with the idiographic personalized formulation, which integrates the perspectives of the clinician, the patient, and his/her family into a jointly understood narrative description of clinical problems, patient's positive factors, and expectations about restoration and promotion of health. The idiographic formulation may be the most effective way to address the complexity of illness, the patient's whole health status and expectations and their cultural framework.

Section 9 organizes the utilization of the information contained in the diagnostic formulation for the purpose of treatment planning. It configures the patient's set of clinical problems by extracting pertinent elements from both the standardized and the idiographic components of the diagnostic formulation. It then delineates an intervention package (including appropriate diagnostic studies as well as treatment and health promoting activities) for each one of the problems listed.

Finally, Section 10 contains recommendations on organizing the clinical chart. Attended to are basic demographic identification data, informational sources and reasons for evaluation, history of psychiatric and general medical illnesses, familial, personal, and social history, psychopathological and physical examination, supplementary assessments, comprehensive diagnostic formulation, and treatment plan. Chart organizing principles that are emphasized include adequate coverage of clinical areas as well as the combination of narrative presentations with semi-structured components as needed. The handling of the clinical charts is expected to ensure safe and efficient accessibility to clinical information as well as maintaining its confidentiality.

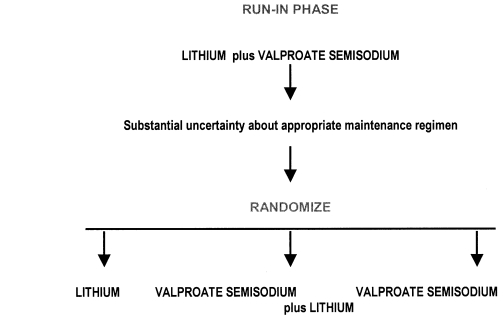

In each section of the Essentials Booklet the following elements are included: a) the ten guidelines corresponding to that section; b) recommended readings, listed in bibliographical form; c) an illustrative diagram, an explanatory table, or an organizing form to facilitate the use of the guidelines. As an example, Figure 1 presents a diagrammatic view of comprehensive diagnostic assessment. The booklet ends with an illustrative clinical case.

Figure 1.

A diagrammatic view of comprehensive diagnostic assessment

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Now that the IGDA Essentials are completed, further work on the IGDA project will focus on its Educational Protocol, a Bases Book, and a Case Book. Additionally, translations to major languages are being considered.

Along with and complementing the development of the IGDA, an empirical assessment of their validity and usefulness for clinical care should be attempted. This should be organized, as much as possible, in diverse national and cultural settings, to determine and ensure their generalizability as is germane to an enterprise of the WPA.

With the IGDA project, the WPA in general and its Section on Classification and Diagnostic Assessment in particular are making an innovative and broadly based contribution to higher standards in international mental health care. A related contribution has been the recent Symposium on International Classification and Diagnosis, organized by the classification components of WPA and WHO within the framework of the WPA European Congress in London, July 2001. A volume emerging from this symposium is being published as a special issue of Psychopathology, the official journal of the WPA Section on Clinical Psychopathology. These contributions illustrate our institutional efforts to work in partnership with the WHO and with national and regional psychiatric associations towards a more integrated and culturally-informed international classification and diagnostic system.

References

- 1.Lain-Entralgo P. El diagnóstico médico. Barcelona: Salvat; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mezzich JE. Jorge MR. Psychiatric nosology: achievements and challenges. In: Costa e Silva JA, Nadelson CC, editors. International Review of Psychiatry. New York: American Psychiatric Press; 1993. pp. 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tasman A. Lost in the DSM-IV checklist: empathy, meaning, and the doctor-patient relationship. Presidential Lecture presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 13–16, 1999; Chicago. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mezzich JE. Fabrega H. Cultural psychiatry: international perspectives. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2001;24:33. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mezzich JE. von Cranach M. Unity and diversity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988. International classification in psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mezzich JE. Honda Y. Kastrup M. Psychiatric diagnosis. A world perspective. New York: Springer; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mezzich JE. An international survey on diagnostic assessment procedures. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatrie. 1993;61:13. [Google Scholar]