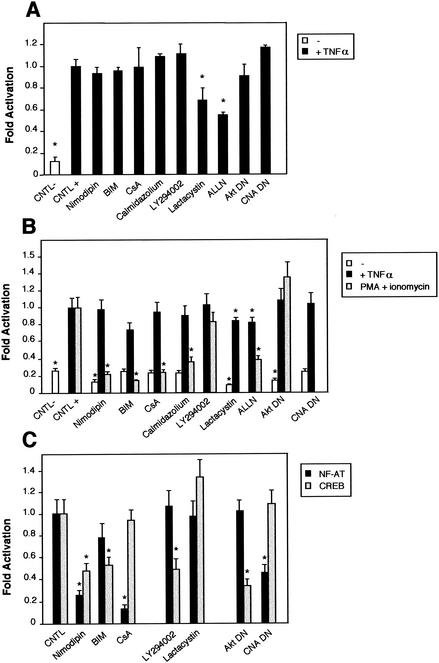

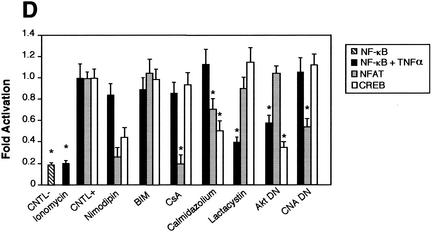

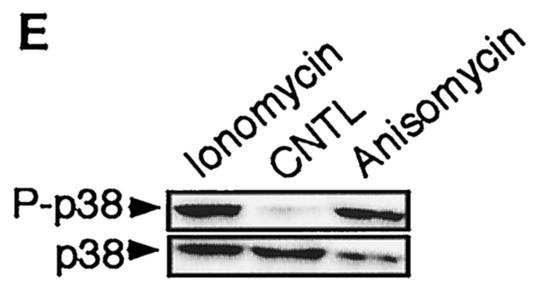

FIG. 11.

Comparison of the NF-κB activity in neurons with the requirement of Ca2+ in other cells. Cells were transfected with 0.75 μg of either the NF-κB-responsive (Igκ)3conaluc, NF-AT, or CREB-responsive plasmid together with 0.25 μg of EF1lacZ normalization vector; cells were treated for 6 h with various inhibitors or solvents 48 h later; and the luciferase as well as the β-galactosidase activities were measured. Data are the means + SE (error bars) of measures done in triplicate, expressed as fractions of the normalized level of activation obtained with cells in standard conditions, and are representative of three independent experiments. Symbols and abbreviations: *, P < 0.01 (significant difference determined by Student's test, compared to the reference); CNTL -, treatment with solvent; CNTL +, treatment with TNF-α and no inhibitors. (A) Ca2+ is not involved in the activation of NF-κB by TNF-α in cerebellar granule neurons. None of the inhibitors of the calmodulin-calcineurin, PKC, or Akt pathways was able to inhibit NF-κB activity, in contrast to proteasome inhibitors like lactacystin or ALLN. (B) NF-κB activity is not affected by inhibitors of the Ca2+ signaling pathways in Jurkat cells treated with TNF-α but is inhibited when activated by PMA plus calcium ionophores. Forty-eight hours after transfection with (Igκ)3conaluc and EF1lacZ plasmids, cells were exposed to various inhibitors of the Ca2+ to NF-κB signaling pathways described above and to TNF-α or ionomycin plus PMA 30 min later, for 6 h. None of the inhibitors shown to specifically inhibit NF-κB basal activity in neurons was active when these cells were stimulated with TNF-α, in contrast to stimulation with PMA plus ionomycin. Note that inhibitors of the PI3K/Akt pathway, LY294002 and Akt, are ineffective in these cell stimulated with PMA and ionomycin. (C) As controls for the activity of the drugs or the dominant-interfering constructs, two vectors containing the luciferase gene controlled by either NF-AT or CREB transcription factors were transfected into Jurkat cells, together with the normalizing plasmid EF1lacZ. NF-AT is activated through the calcium/calmodulin/calcineurin pathway, and CREB is responsive to the calcium/calmodulin kinases as well as to Akt. Drugs similar to those used in panel B were used for 6 h, 48 h after transfection, and the activities were measured immediately thereafter. (D) Inhibitors of Ca2+ signaling are unable to antagonize NF-κB activation in HeLa cells stimulated by TNF-α. Forty-eight hours after transfection with (Igκ)3conaluc and EF1lacZ plasmids, cells were exposed to various inhibitors of the Ca2+ to NF-κB signaling pathways described above and to TNF-α 30 min later, for 6 h. With the exception of lactacystin and of the expression of a dominant-negative construct of Akt, none of the inhibitors shown to specifically inhibit NF-κB basal activity in neurons was active in these cells. Cells were exposed to ionomycin to show that Ca2+ entry does not stimulate NF-κB activity in these cells. As controls for the efficiency of the pharmacological agents and of the dominant-negative constructs, HeLa cells were transfected in parallel with NF-AT and CREB-responsive reporter vectors. The same parameters as those used for (Igκ)3conaluc were used. (E) p38 kinase is activated by calcium entry in HeLa cells. HeLa cells were treated with anisomycin (1 μM), a specific activator of the p38 pathway, or ionomycin (1 mM), a calcium ionophore, for 1 h. Cellular extracts were subjected to immunoblot analysis with a primary antibody directed against phosphothreonine 180 and phosphotyrosine 182, indicative of p38 activation (P-p38). To check for correct loading, same extracts were analyzed using an antibody directed against the whole p38 (p38).