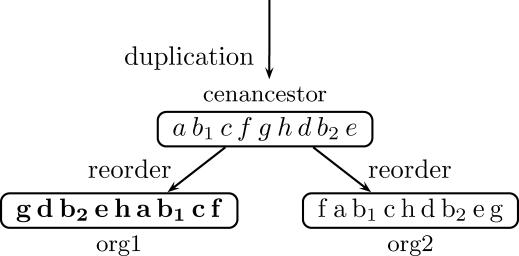

Figure 1. A Hypothetical Example Demonstrating the Definition of Positional Orthologs and the Emergence of a Nuisance Cross-Overlap.

A portion of the genomic segments in a hypothetical cenancestor is denoted by letters. Their orthologous segments in the descendant organisms org1 and org2 are given, using the same letters, but in different font (to stress that the segments, despite being orthologous, are similar but not identical). The scenario described in this example is as follows: a duplication of a genomic segment results in two duplicates b 1 and b 2 in the cenancestor. During the speciation of org1 and org2 the cenancestor genomic segments are shuffled. The orthologous segments b1 and b1 have similar genomic contexts and are thus positional orthologs. Similary b2 and b2 are positional orthologs as well. When comparatively mapping org1 and org2, one would find that b1 is similar to b2 and b2 is similar to b1. These hits obscure the deduction of the true evolutionary relation between b1 and b1 as well as between b2 and b2, and are referred to as nuisance cross-overlaps. In real biological examples, similar situations arise, e.g., because of rDNAs; see Figure 2. Notice also that, unlike in sequence alignment, and as is demonstrated in this example, duplications that occurred before the cenancestor (referred to sometimes as outparalogs [3]) may cause hardships when comparatively mapping two organisms. Thus, nuisance cross-overlaps can be thought of as an “ancestral curse.”