Abstract

Centromeric heterochromatin comprises ∼30% of the Drosophila melanogaster genome, forming a transcriptionally repressive environment that silences euchromatic genes juxtaposed nearby. Surprisingly, there are genes naturally resident in heterochromatin, which appear to require this environment for optimal activity. Here we report an evolutionary analysis of two genes, Dbp80 and RpL15, which are adjacent in proximal 3L heterochromatin of D. melanogaster. DmDbp80 is typical of previously described heterochromatic genes: large, with repetitive sequences in its many introns. In contrast, DmRpL15 is uncharacteristically small. The orthologs of these genes were examined in D. pseudoobscura and D. virilis. In situ hybridization and whole-genome assembly analysis show that these genes are adjacent, but not centromeric in the genome of D. pseudoobscura, while they are located on different chromosomal elements in D. virilis. Dbp80 gene organization differs dramatically among these species, while RpL15 structure is conserved. A bioinformatic analysis in five additional Drosophila species demonstrates active repositioning of these genes both within and between chromosomal elements. This study shows that Dbp80 and RpL15 can function in contrasting chromatin contexts on an evolutionary timescale. The complex history of these genes also provides unique insight into the dynamic nature of genome evolution.

EUKARYOTIC genomes contain cytologically distinct euchromatic and heterochromatic domains. Euchromatin decondenses regularly during the cell cycle, consists primarily of single-copy sequences (including genes) and is transcriptionally active, while heterochromatin appears condensed throughout the cell cycle, consists mainly of repetitive sequences, and can silence gene expression (Avramova 2002; Grewal and Elgin 2002; Craig 2005). Heterochromatin accounts for a considerable portion of many eukaryotic genomes, remains largely uncharacterized due to its repetitive nature, and poses significant challenges for genome sequence assembly (Mardis et al. 2002). In the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, heterochromatin comprises approximately one-third of the genome and is organized primarily into pericentromeric and telomeric blocks (reviewed by Pimpinelli and Wakimoto 2003 and references therein). Small intercalary blocks of heterochromatin are also dispersed throughout the euchromatic chromosome arms (Zhimulev and Belyaeva 2003).

A small number of essential genes have been identified in autosomal heterochromatin of D. melanogaster (Hilliker and Holm 1975; Hilliker 1976; Marchant and Holm 1988a,b; Schulze et al. 2001; reviewed by Coulthard et al. 2003; Dimitri et al. 2005; Fitzpatrick et al. 2005). Their ability to function in this inactivating environment is puzzling, as is their repression when moved to distal sites within euchromatin (Wakimoto and Hearn 1990; Eberl et al. 1993). There is also genetic and molecular evidence indicating that heterochromatic gene expression is dependent on constituents of heterochromatin even in the absence of chromosomal rearrangements. For example, genes in heterochromatin exhibit compromised transcription in a genetic background deficient for heterochromatin-associated protein (Clegg et al. 1998; Lu et al. 2000; Sinclair et al. 2000; Schulze et al. 2005). Thus, the regulation of heterochromatic loci and the dependence of gene expression on the surrounding chromatin environment are intensely active areas of research.

A number of issues have impeded progress in the genetic and molecular characterization of centric heterochromatin using standard methods. These problems include the absence of good polytene banding, the lack of standard meiotic recombination, and the presence of numerous repetitive DNA sequences. Release 3 of the Drosophila genome sequence contains ∼21 Mb of putative heterochromatic DNA (Hoskins et al. 2002). These data are extremely valuable in providing both an overview and a preliminary model for the molecular organization of heterochromatic genes, although there are questions concerning the discrepancy between the numbers of predicted (at least 300) gene models vs. the few dozen essential loci defined by genetic methods. An additional difficulty concerning the molecular analysis of heterochromatic genes is presented by their size: most that have been characterized to date tend to be very large, due to the presence of repetitive sequences in their introns (Devlin et al. 1990a,b; Risinger et al. 1997; Warren et al. 2000; Tulin et al. 2002; Dimitri et al. 2003; Schulze et al. 2005).

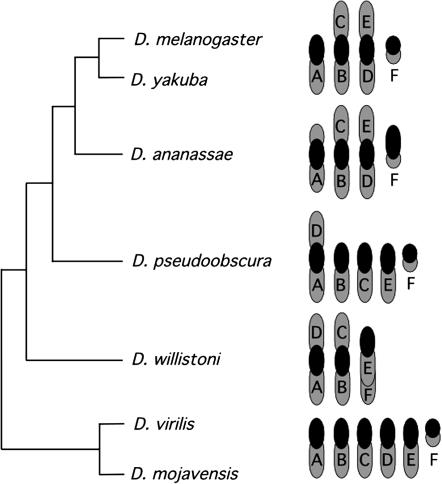

Another puzzle to be addressed is how genes come to reside and function in such a transcriptionally repressive environment. One way of elucidating the evolutionary history of heterochromatic genes is to examine the structure and position of these genes in a set of related species. The genus Drosophila is ideal for a comparative study of heterochromatic genes: it consists of a large number of well-studied species and possesses a relatively stable karyotype, while nevertheless exhibiting exceptionally malleable evolutionary dynamics at the intrachromosomal level. Six chromosomal elements, identified with letter designations to indicate homology (“Muller elements”), are the basis for chromosomal organization in the genus (Muller 1940). Gene content of the chromosomal elements is largely shared among species, and movement between elements is considered unusual, but genes are extensively rearranged within elements (Vieira et al. 1997; Ranz et al. 2003). Chromosome number differs among Drosophila species due to large-scale rearrangements involving fusion events between acrocentric chromosomes that produce metacentric arrangements. This is exemplified by comparing the chromosomal configurations of representative species in Figure 1. For example, the haploid karyotype of D. virilis possesses the inferred ancestral condition with six acrocentric chromosomes. D. melanogaster has only four chromosomes in the haploid set due to two fusion events that formed the large metacentric autosomes, whereas D. pseudoobscura has five chromosomes with one of these resulting from a fusion event between elements A (the X chromosome) and D.

Figure 1.—

Organization of the six chromosomal elements in haploid female genomes of representative Drosophila species. Each chromosomal arm is labeled with its Muller element designation based on Table 9-4 from Powell (1997) with exceptions/additions for D. ananassae (Tobari 1993), D. willistoni (Papaceit and Juan 1998), and D. mojavensis (Wasserman 1982). The consensus relationships among species are represented by the cladogram disregarding absolute times of divergence.

In this report, two genes located deep within the pericentromeric heterochromatin of Muller's element D (3L) in D. melanogaster were characterized extensively in the genomes of D. virilis and D. pseudoobscura. In D. melanogaster, the extremely large Dbp80 gene encodes a DEAD box RNA helicase, with exons spread over >140 kb of genomic DNA containing an abundance of repetitive sequences. DmDbp80 resides ∼10 kb downstream of a highly active gene, DmRpL15, which encodes an essential component of the ribosome (Schulze et al. 2005). DmRpL15 is surprisingly small for a heterochromatic gene, although it is likewise characterized by the presence of repetitive DNA upstream, downstream, and within its introns.

General evolutionary constraints on these genes, and the resultant diversity in gene structure and location, were determined through a comparative genomic framework. The genes are not adjacent to each other in the genome of D. virilis and appear to reside on separate chromosomal elements in this species. DvDbp80 is a small gene located on element D in euchromatin, while DvRpL15 is similar to D. melanogaster in both structure and heterochromatic position, but is on element E in D. virilis. In D. pseudoobscura, the genes are adjacent to each other as they are in D. melanogaster and have retained their fundamental structures. Surprisingly, however, in D. pseudoobscura, they are located in the middle of the euchromatic portion of element E. These genes have therefore undergone a rare interelement relocation at least twice during the course of Drosophila evolution, and these movements have been confined to the chromosomal elements (D and E) that form the metacentric chromosome 3 in D. melanogaster. In addition, both genes present a study in contrasts with respect to gene structure. Collectively, these findings provide novel insight into the dynamic nature of Drosophila heterochromatin and into how the local environment influences gene structure in relation to functional constraints.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Southern and Northern analysis:

Drosophila genomic DNA was isolated using the method outlined by Jowett (1998). Genomic DNA from adult flies was cut with 40–60 units of EcoRI and electrophoresed overnight in 0.5× TBE in a 0.7% agarose ethidium bromide gel. The gel was photographed, measured, trimmed, and treated for Southern transfer as described in Sambrook (1989). For intraspecific Southern analysis, prehybridization and hybridization were carried out at 68° in a solution of 50 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 100 mm sodium dihydrogen phosphate, and 7% SDS, with salmon sperm DNA used as a blocking agent. The probes were labeled by random priming with P32 (DNA random prime labeling kit from Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis). The blots were washed in FSB 1% SDS and exposed to X-ray film. Total RNA was obtained from adult flies using Trizol, following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA samples (30 μg) were fractionated in formaldehyde agarose gels and transferred to Hybond N+ nylon membranes. Labeling and hybridization were carried out as described above for Southern analysis.

Isolation of D. virilis cDNAs:

The D. virilis cDNAs were isolated from a mixed embryonic plasmid library in pOT7B constructed for the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (http://www.fruitfly.org/) and kindly provided by Ling Hong. Plasmid libraries were screened in three stages, with the primary screen plated with liquid culture to near confluence, the secondary plates patched, and the tertiary plates streaked to ensure unique isolates. Colonies were grown overnight on 2YT agar plates with 25 μg/μl chloramphenicol and then transferred to 4° for at least 2 hr before treatment with nylon filters (lifts). In all cases, Hybond-N+ (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) circular filters were used. The filters with colonies were transferred to fresh plates, which were placed at 37° for a minimum of 4 hr, after which the filters were twice soaked (colony side up) for 3 min in denaturing solution (1.5 n NaCl, 0.5 n NaOH) and then once in neutralizing solution (0.5 m Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1.5 n NaCl) for 7 min. They were then rinsed in 2× SSC, and the colony debris actively scrubbed off. After the filters were drained briefly on Whatman filter paper, they were irradiated with UV light using a Stratagene (La Jolla, CA) stratalinker and subjected to hybridization under the conditions described above for genomic Southern analysis, except that the stringency was lower (6× SSC, 2× Denhardt's, 0.5% SDS, 59°). Putative clones were purified after the tertiary screen by alkaline lysis (Sambrook et al. 1989) and inserts were sequenced by the University of Calgary Core DNA and Protein services (accession no. DQ426903 for DvRpL15 and DQ426902 for DvDbp80).

In situ chromosome analysis:

Preparation of chromosome squashes from the salivary glands of third instar larvae of D. virilis was as described by Kress (1993). Probes were labeled by nick translation with biotin-14-dATP (Invitrogen Life Technologies, San Diego) or digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After hybridization at 37° overnight, and three washes in 2× SSC, signal was detected with antidigoxygenin–rhodamine (Roche Diagnostics) at a 1:550 dilution, or with antibiotin-FITC (Vector Laboratories) diluted 1:45 for 1 hr. DNA was counterstained with DAPI before image capture, using a cooled CCD camera (MicromaxYHS 1300, Roper Scientific) mounted on a DMRXA Leica microscope. Polytene in situ analysis for D. pseudoobscura and mitotic (from neuroblasts) in situ analysis for D. virilis were carried out according to Pimpinelli et al. (2000). Probes were differentially labeled by nick translation with digoxigenin- or biotin-coupled dUTP and detected with fluorescein avidin or antidigoxigenin–rhodamine antibody. For D. virilis, either cDNA (for polytene chromosomes) or genomic DNA (for mitotic chromosomes) probes were used. For the latter, a DvRpL15 probe was prepared by labeling a 3.5-kb EcoRI subclone (also having an internal EcoRI site), which contains the DvRpL15 gene and just under 1 kb of flanking sequence on either side. The DvDbp80 probe was prepared by labeling a 4.6-kb EcoRI fragment containing the DvDbp80 gene. For D. pseudoobscura polytene analysis, probes were prepared by PCR amplification from genomic DNA of unique sequences containing the genes in question, and primer selection was based upon the published genome sequence (at http://www.genome.gov/11008080, the portal for the comparative Drosophila genome-sequencing project). Therefore, for DpRpL15, two primers, 5′-GGGCCTATCGTTATATGCAAG-3′ and 5′-ACGGTTCTTGCGCTTCCAGGC-3′, were chosen to amplify a 760-bp probe, while 5′-CTGAGTGGTAATCTGGTCA-3′ and 5′-TAATGCTATCCAGTGTTCGA-3′ amplified an 870-bp probe for DpDbp80.

Phage library screening:

The genomic regions for DvRpL15 and DvDbp80 were subcloned from a phage λEMBL3 D. virilis genomic library (Thummel 1993), generously provided by Ron Blackman. Phage libraries were screened using the D. virilis cDNAs as probes in three stages: for the primary screen, plates were almost confluent, and the secondary and tertiary screens were plated at low titer to ensure unique isolates. Phage were plated in NZYM Top agarose (Sambrook et al. 1989), grown overnight, and then transferred to 4° for at least 2 hr before transfer to filters (lifts). Hybond-N+ (Amersham) circular filters were used for plate lifts and treated with the same denaturing and neutralizing solutions described above for plasmid library screening. The filters were rinsed briefly in 2× SSC, drained on Whatman filter paper, irradiated with UV light using a Stratagene stratalinker, and subjected to hybridization under the conditions described above. Genomic inserts from positive phage were cut with SalI to liberate the inserts. The restriction digest products were then diluted, run on an agarose gel, transferred to nylon membrane by Southern blotting, and hybridized with relevant cDNA probes to establish which bands contained coding regions. These bands were then extracted, using a GFX gel extraction kit (Amersham) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and subcloned into pBluescript. Small SalI fragments were also gel extracted and cloned into SalI-cut pBluescript.

Sequence analysis:

Sequence assembly (D. virilis genomic subclones) was carried out using the BLAST algorithm for two sequences (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/tracemb.shtml). Identifying D. virilis coding and noncoding regions was carried out using BLASTN and TBLASTN on genomes of those model organisms that have already been sequenced. All the default BLAST settings were used, except that low-complexity sequence was not masked. Multiple protein or nucleic acid alignments were made first by using CLUSTAL W (Thompson et al. 1994) to generate the alignments and then BOXSHADE (Boxshade version 3.3.1 by Kay Hofmann and Michael D. Baron) for coloring conserved regions. CLUSTAL W and BOXSHADE are available at http://workbench.sdsc.edu/. Sequencing was carried out by the University of Calgary Core DNA and Protein Services and assembled (see below). Accession numbers are DQ426901 (DvDbp80 genomic) and DQ426900 (DvRpL15 genomic).

Bioinformatic analysis:

Sequence of the DmDbp80 and DmRpL15 region in the D. melanogaster genome was obtained from GenBank (accession no. AABU01002497) along with the cDNA sequences of these genes (accession nos. AF005239 and AY094841, respectively). Sequences of cDNAs for both Dbp80 and RpL15 were constructed from 5′ and 3′ EST reads of D. pseudoobscura and D. ananassae available from the NCBI Trace Archive (deposited by the Human Genome Sequencing Center at Baylor and Agencourt Bioscience). The cDNA sequence of RpL15 was also available for D. yakuba (AY231804; Domazet-Loso and Tautz 2003). Genomic sequences were obtained from the following sources: D. pseudobscura (Human Genome Sequencing Center at Baylor, Release 1.0; Richards et al. 2005), D. yakuba (Genome Sequencing Center at Washington University, release 1), D. willistoni (J. Craig Venter Institute, NCBI Trace Archive), and D. ananassae, D. virilis, and D. mojavensis (Agencourt Bioscience, freeze 1 assemblies). Sequences of Dbp80 and RpL15 were identified in each genome sequence using blastn (Altschul et al. 1997). A CLUSTAL W alignment was obtained for the D. melanogaster, D. pseudoobscura, and D. virilis cDNA sequences of Dbp80 with genomic sequences from D. virilis and D. mojavensis. Positions of exon/intron boundaries were inferred by the position of gaps and conserved splice sites. Positions of exon/intron boundaries in the remaining species were inferred from BLAST alignments of cDNA sequences with genomic sequences. The most similar cDNA sequence was used as the query for each of the alignments. A CLUSTAL W alignment of RpL15 was obtained for the cDNA and genomic sequences of all species, and the positions of the two conserved introns were inferred from gaps and splice sites in the alignment. Genomic context of the Dbp80 and RpL15 genes in each of the genomes was assessed on the basis of the initial assemblies. Contigs containing these genes were screened for the presence of repetitive sequences using Repeat Masker to mask repeats in a sequence (http://www.repeatmasker.org). Furthermore, the presence of genes in the masked contig was assessed using the NCBI BLAST server to screen the D. melanogaster genome. Inferences of gene content were also evaluated in the annotations represented in the UCSC Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu).

RESULTS

Cloning and characterization of Dbp80 and RpL15 in D. virilis:

RpL15 and Dbp80 present contrasting structures in D. melanogaster, where they are located next to each other deep within the heterochromatin of the left arm of chromosome 3 (element D). RpL15 is a small, highly expressed gene consisting of three exons that encodes an essential component of the ribosome, whereas Dbp80, which encodes a nonessential DEAD box RNA helicase, is hugely extended, with its 11 exons covering >140 kb of DNA (Schulze et al. 2005). Both genes are embedded within a repetitive sequence environment.

To initiate a study of the evolutionary history of these genes, cDNAs for both were isolated in a low-stringency screen of a mixed embryonic D. virilis plasmid cDNA library using D. melanogaster probes. For DvRpL15, a single transcript was obtained; for DvDbp80, two transcripts resulted, differing only slightly in length at the 5′-end. Both genes encode products that are comparable in size to their D. melanogaster orthologs. cDNA sequences are available for D. pseudoobscura and Anopheles gambiae, two additional dipteran species that have assembled genome sequences (Holt et al. 2002; Richards et al. 2005). Alignments of the conceptually translated sequences of both genes from the four available dipteran species with sequences of the human and yeast orthologs are shown in Figure 2, A and B. All of the Dbp80 sequences possess a unique six-amino-acid residue motif indicative of DEAD box helicases, which in yeast have been shown to be involved in mRNA export (Snay-Hodge et al. 1998; Rollenhagen et al. 2004). Southern and Northern analyses of both genes in D. virilis demonstrate that they are likely to be single copy and expressed in a manner similar to that of their D. melanogaster orthologs (data not shown). A BLAST search of D. virilis sequence traces in the NCBI Trace Archive also revealed single haplotypes, indicating that both genes are present in single copy. Since both genes appear to be single copy and functional in this distantly related species, they are good candidates for a study of heterochromatic gene evolution.

Figure 2.—

Alignments of (A) DBP80 and (B) RpL15 proteins across selected taxa. The six-amino-acid residue placing DBP80 into the DBP5 family of proteins is marked by asterisks in A.

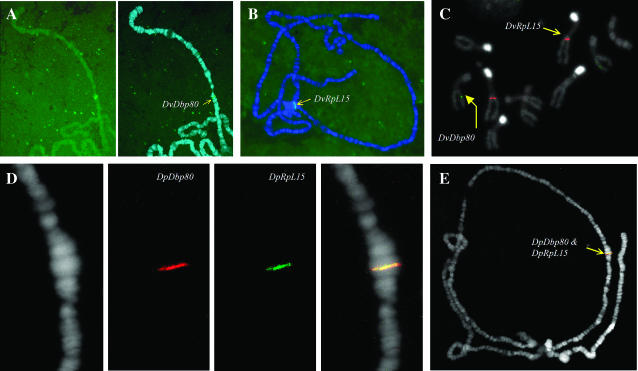

Chromosomal in situ analysis of Dbp80 and RpL15 in D. virilis and D. pseudoobscura:

To determine whether these genes were adjacent and heterochromatic in species other than D. melanogaster, chromosomal in situ analysis using cDNA probes was performed in D. virilis and D. pseudoobscura. As is typical for dipteran polytene chromosome spreads, the heterochromatic regions of all the chromosomes aggregate into an undifferentiated mass called the chromocenter. A consistent chromocenter signal in a polytene in situ hybridization analysis therefore indicates a heterochromatic location.

The in situ data are shown in Figure 3. For both species, a single signal resulted in each case, supporting the molecular and bioinformatic evidence that Dbp80 and RpL15 exist as intact single copies in these genomes. Both genes reside in the heterochromatin of element D (3L) in D. melanogaster, but this arrangement is not conserved in D. virilis or D. pseudoobscura. In D. virilis, Dbp80 appears to be euchromatic (Figure 3A), mapping approximately to position 35F (Kress 1993) on chromosome 3, which is element D and therefore homologous to 3L in D. melanogaster (see Figure 1). DvRpL15, on the other hand, consistently gave a chromocenter signal (Figure 3B), indicating that this gene is heterochromatic in this species. To establish on which chromosome arm DvRpL15 resides, it was necessary to perform an in situ analysis on fully condensed mitotic chromosomes, which showed that this gene is located on a different chromosomal element than DvDbp80 (Figure 3C). The identity of this element can be inferred from two observations. First, the DvRpL15 probe hybridized to a homologous chromosome pair with a centromeric region that stains brightly with DAPI. Previous studies (Holmquist 1975) demonstrate bright staining of the centromeres of chromosome 2 and 4 with Hoechst, and although DAPI was used as the counterstain in this analysis, the two fluorochromes exhibit identical staining patterns (Pimpinelli et al. 2000), probably due to their high affinity for AT-rich regions. Second, rare polytene spreads were observed in which the heterochromatic region bearing the DvRpL15 signal was pulled out from the chromocenter and clearly linked to chromosome 2, which has the longest polytenized euchromatic arm in this species (data not shown). Collectively, the cytological evidence indicates that in D. virilis, RpL15 is located in heterochromatin on element E (chromosome 2), while Dbp80 is located in euchromatin on element D (chromosome 3).

Figure 3.—

Chromosomal in situ analysis in D. virilis (A–C) and D. pseudoobscura (D and E). DvDbp80 and DvRpL15 are on different elements and in different chromosomal contexts. DvDbp80 is in euchromatin on chromosome 3, determined by polytene banding (A), while DvRpL15 appears to be located in the heterochromatic chromocenter (B). Specifically, DvRpL15 is located on chromosome 2, determined from the bright centromere staining in the mitotic spreads (C) and from rare polytene preparations in which chromosome 2 was pulled away from the chromocenter (data not shown). Note from the mitotic spreads (C) that RpL15 (red signal) appears to be located in distal heterochromatin, possibly near the heterochromatic/euchromatic border. This image also suggests how extensive heterochromatin is in the D.virilis genome, occupying fully half the mitotic chromosome length. The two genes are adjacent in D. pseudoobscura, located in the middle of chromosome 2 in this species (D and E).

D. pseudoobscura represents a species that occupies an intermediate position between D. virilis and D. melanogaster with respect to evolutionary divergence (Figure 1). When D. pseudoobscura probes were labeled and hybridized to D. pseudoobscura polytene chromosomes, the two genes were observed to colocalize in the middle of the euchromatic portion of what appears to be element E (chromosome 2 in this species—Figure 3, D and E). This surprising result indicates that both genes are on a different element in D.pseudoobscura relative to their position in the genome of D. melanogaster.

Dbp80 gene structure is evolutionarily dynamic while RpL15 is highly conserved:

The in situ data provide clear evidence of at least two interelement movements involving Dbp80 and RpL15 during the evolutionary history of these species. It is also clear, that while Dbp80 and RpL15 are different in terms of gene structure and biological function (Schulze et al. 2005), their activity is not dependent on chromatin environment, since it appears that both can exist in heterochromatin or euchromatin. To study the connection between gene structure and genomic context, we employed a combination of molecular and bioinformatic approaches to determine the structure for each gene in seven Drosophila species (see Figure 1). As a starting point, the gene structures in D. virilis were determined by cloning and characterizing genomic sequence: D.virilis cDNAs were used in high-stringency screens of a D. virilis phage genomic library and the genomic structures for both genes were resolved by alignment. Sequences derived from these clones were compared with the sequence obtained from the Agencourt whole-genome assembly for D. virilis (freeze 1 assembly). In addition, cDNAs for Dbp80 and RpL15 from D. virilis, D. pseudoobscura, and D. melanogaster were used to determine the genomic organization for both genes in five additional species (D. yakuba, D. ananassae, D. pseudoobscura, D. willistoni, and D. mojavensis) that form a part of the Drosophila comparative genome-sequencing project (http://www.genome.gov/11008080). As a potential outgroup for comparison, genomic structures were also derived by analysis of cDNA and genomic sequence obtained from the Anopheles genome project (http://www.ensembl.org/Anopheles_gambiae/).

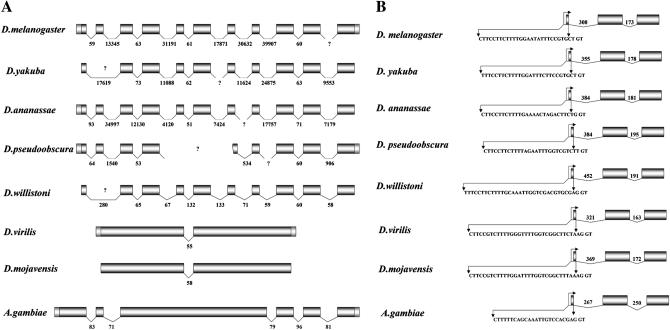

As can be seen in Figure 4A, Dbp80 exhibits an evolutionarily labile structure: it is extended in genomic size with many introns in species of the subgenus Sophophora (D. willistoni, D. pseudoobscura, D. ananassae, D. yakuba, and D. melanogaster) and condensed with only a single intron in species of the subgenus Drosophila (D. mojavensis and D. virilis). This single intron is conserved both in position and approximate size in species from both subgenera. Where contiguous sequence is available, the extended Dbp80 is interrupted by introns in precisely the same positions in all species of the subgenus Sophorphora; however, intron sizes vary remarkably among these species. The structure of Dbp80 in An. gambiae is intermediate, with five introns, but these appear to be completely conserved in position with respect to species in the Sophophoran lineage. The same comparative study for RpL15 reveals a contrasting picture: this gene retains its structure throughout all species examined (Figure 4B), including the polypyrimidine tract that has been shown to play an important role in both the transcriptional and translational regulation of ribosomal protein genes across taxa (Hariharan and Perry 1990; Levy et al. 1991; Barakat et al. 2001). Thus Dbp80 appears to tolerate great flexibility with respect to genomic organization, while the structure of RpL15 has remained highly conserved during the divergence of these lineages.

Figure 4.—

Comparative gene organization for (A) Dbp80 and (B) RpL15 in six Drosophila species and An. gambiae. cDNA sequences were available for D. melanogaster, D. yakuba (DyRpL15 only), D. ananassae (5′ EST for DaDbp80 only), D. pseudoobscura, D. virilis, and An. gambiae, and these cDNA sequences were used in alignment to resolve the gene structures from available genomic sequence for the cognate species. Where cDNA sequence was not available, the most closely related cDNA sequence was used (for example, the D. virilis cDNA was used to resolve the D. mojavensis gene structure, etc.) The sequence of the second exon of Dbp80 is not well conserved across species in the Sophophoran sublineage and therefore not detectable in the current assemblies of the D. yakuba and D. Willistoni genomes.

Genomic context of Dbp80 and RpL15 in D. virilis and D. melanogaster:

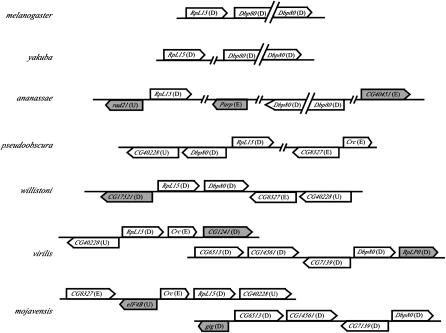

Dbp80 and RpL15 are associated with repetitive DNA that is known to be in heterochromatin in D. melanogaster (Hoskins et al. 2002; Schulze et al. 2005). Our cytological analysis shows that RpL15 is also heterochromatic in D. virilis. In addition, our analysis of the genomic context for both genes in this species indicates contrasting DNA environments. Sequences from the DvDbp80 genomic region were readily recovered from a phage genomic library, and a total of almost 20 kb was assembled from the sequence of overlapping clones (data not shown). Within our assembly, we identified several other genetic elements in addition to DvDbp80, all supported by the Agencourt genome sequence (http://www.genome.gov/11008080) for this region. The ortholog of CG7139 in D. melanogaster, which encodes a conserved function in DNA repair (Eisen 1998), resides <1 kb upstream and is transcribed in the opposite direction (Figure 5). Farther upstream of DvCG7139 there are sequences homologous to a small gene in D. melanogaster called CG14561, which encodes a product of unknown function. All three of these genes are located on the same chromosomal element (D) in D. melanogaster. An instance of microsynteny is exhibited by the conservation of the arrangement of CG7139 and CG14561 in both species. A large Ulysses retrotransposon is downstream of DvDbp80 in the sequence assembled from the phage library clones. This retrotransposon appears to be intact (data not shown), so it is potentially still active. Interestingly, a Ulysses element is not present in this region of the assembled genome of D. virilis produced by Agencourt, which may reflect the polymorphic location that has been reported for this transposable element (Evgen'ev et al. 2000 and discussion).

Figure 5.—

Representation of genes flanking RpL15 and Dbp80 in seven species of Drosophila. Each line represents a contiguous sequence from that species, and the lines are oriented in the same horizontal plane when linking information indicates that they are closely associated in a scaffold. The arrowhead indicates the direction of transcription for each identified gene. The chromosomal (Muller's) element association of each gene relative to D. melanogaster is indicated in parentheses. Genes in the vicinity of RpL15 or Dbp80 in more than one species are indicated by an open background and those in only one species by a shaded background.

Genomic sequences for DvRpL15 were more difficult to clone and assemble and, on the whole, had a higher content of repetitive DNA. Approximately 4 kb of genomic DNA containing RpL15 coding sequences was assembled, and there are no other genetic elements in the immediate vicinity. However, this region maps to a 145-kb contig in the assembled genome sequence of D. virilis, and although 34% of the sequence consists of interspersed repeats (Table 1), other genes, including CG9429 (Calreticulin, or Crc) and CG1241, are identifiable in the sequence. Interestingly, these two genes are located on different chromosomal elements in D. melanogaster, representing elements E and D, respectively. Another gene (CG40228) matching the RE67573 cDNA of D. melanogaster, which has not been localized to a chromosomal arm in this species (armU), appears immediately upstream of DvRpL15.

TABLE 1.

Chromosomal position and repetitive sequence context for Dbp80 and RpL15 in species from the genus Drosophila

| Drosophila species | Adjacent | Dbp elementa | Dbp %ISb | RpL elementa | RpL %ISb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| melanogaster | Yes | Dh | 60 | Dh | 60 |

| yakuba | Yes | ? | 45 | ? | 45 |

| ananassae | No | Mosaic | 12 | Mosaic | 14 |

| pseudoobscura | Yes | Mosaic (E) | 12 | Mosaic (E) | 12 |

| willistoni | Yes | Mosaic | 0 | Mosaic | 0 |

| virilis | No | melD (D) | 2.2 | Mosaic (Eh) | 34 |

| mojavensis | No | melD | 0.24 | Mosaic | 1.3 |

Positions of flanking genes in D. melanogaster; mosaic indicates matches to multiple chromosomal arms, including unplaced transcripts (armU); question mark indicates a lack of identifiable orthologs in the surrounding sequence, letters in parentheses indicate positions based on in situ hybridization.

Percentage of sequence identified as interspersed repeats in the region containing the gene.

In summary, a combined molecular and bioinformatic analysis of the genomic regions containing Dbp80 and RpL15 in D. virilis supports the in situ data showing contrasting chromatin environments for these genes. Dbp80 is euchromatic in this species, located within a genomic context containing other genes mapping to element D, which is the homologous arm (3L) in D. melangaster, consistent with the reported restriction of genes to conserved chromosomal elements (Ranz et al. 2003). RpL15, by contrast, is heterochromatic in D. virilis and in a genomic context that exhibits an interesting mosaic of genes from different chromosomal elements in the D. melanogaster genome.

Genomic context and arrangement of Dbp80 and RpL15 in other Drosophila species:

Analysis of the flanking sequence of both Dbp80 and RpL15 throughout the genus Drosophila is possible using the data available from the comparative genome-sequencing project (http://www.genome.gov/11008080). From genome sequence data, the position of these genes relative to each other, and the identity of genes in flanking regions can be determined. The in situ data indicate that these genes are very close to each other in D. pseudoobscura (Figure 3, D and E), and the location of these genes in the assembled sequence also demonstrates that they are adjacent, but they are not transcribed in the same orientation as in D. melanogaster (Figure 5). Analyses of the available genome sequence data from D. yakuba and D. willistoni indicate that Dbp80 and RpL15 are located close to each other in a scaffold and a contig, respectively, and thus are likely adjacent in these species as well. These genes are located on the same scaffold in D. ananassae, but are separated by ∼2 Mb of intervening sequence. On the basis of in situ hybridization in D. virilis, the genes are present on different chromosomal elements (Figure 3C), supported by the observation that they are located in different large scaffolds of assembled D. virilis genomic sequence. Similar results were also obtained for D. mojavensis. Therefore, Dbp80 and RpL15 are adjacent in all of the species in the subgenus Sophophora, except D. ananassae, and they are separate in the two representatives of the subgenus Drosophila (Table 1).

Repeat content of the sequence in the immediate vicinity of Dbp80 and RpL15 and the position of additional identifiable orthologs of D. melanogaster provide further indication of the surrounding genomic environment. The region surrounding Dbp80 in D. virilis contains few interspersed repeats (Table 1), consistent with the euchromatic localization of this gene determined by in situ hybridization (Figure 3A). The genomic context of Dbp80 in D. virilis appears to be conserved with D. mojavensis, including the relative positions of the flanking genes CG6513, CG14561, and CG7139 (Figure 5), which indicates microsynteny for this region in these two representative species of the subgenus Drosophila. The genes in this conserved region are all located on element D of D. melanogaster.

The region surrounding RpL15 contains an abundance of interspersed repeats in all the species examined, with the exception of D. willistoni and D. mojavensis (Table 1). Although repeat content differs in the region around RpL15 between D. virilis and D. mojavensis (Table 1), two single-copy genes [Crc (CG9429) and CG40228] flanking RpL15 are conserved between these species (Figure 5). Conservation of genes around RpL15 (and including Dbp80 when adjacent) is also evident in comparison with species in the subgenus Sophophora (Figure 5). The most striking of these conserved flanking genes is CG40228, which is present in single copy and near RpL15 in D. pseudoobscura, D. willistoni, D. virilis, and D. mojavensis, and thus reflects a conserved ancestral arrangement. The proximity of RpL15 and CG40228 in the genome of D. melanogaster remains difficult to assess on the basis of the current heterochromatic assembly. In D. virilis, D. mojavensis, and D. willistoni, genes flanking RpL15 are present on either element D or element E in the genome of D. melanogaster, which corresponds to the left and right arms of chromosome 3 (Figure 1). Thus, whereas Dbp80 is associated with two different sets of flanking genes in the subgenera Drosophila and Sophophora, RpL15 is embedded among a number of conserved genes in both lineages.

The high density of interspersed repeats surrounding RpL15 is consistent with the heterochromatic location in D. virilis and D. melanogaster, but the relatively high density of repeats around RpL15 is not consistent with its apparent euchromatic position in D. pseudoobscura. Additionally, the region directly flanking RpL15 and Dbp80 in the assembled genome of D. pseudoobscura contains several other genes present on element D of D. melanogaster (Figure 5), which is inconsistent with the in situ localization of probes of both Dbp80 and RpL15 to element E of D. pseudoobscura (Figure 3, D and E). However, this discrepancy may be misleading, because the original scaffold (Contig3286_Contig7811B) containing Dbp80 and RpL15 is a manual subdivision of a larger scaffold (Contig815_Contig5737) obtained from the automated assembly (Richards et al. 2005). Interestingly, the adjacent subdivided scaffold (Contig4971_Contig7717A) contains both CG8327 and Crc, which are near RpL15 in several other species (Figure 5). Therefore, the Dbp80 and RpL15 genes in D. pseudoobscura reside in a moderately repetitive environment in the middle of element E, and this has been confirmed in the current reassembly of the genome (S. Schaeffer, personal communication). Furthermore, this region contains a mosaic of genes from elements D and E of D. melanogaster.

DISCUSSION

The heterochromatic location of Dbp80 and RpL15 in D.melanogaster is not conserved throughout the genus Drosophila:

The combined molecular and bioinformatic analysis reported here demonstrates that Dbp80 and RpL15 are present as intact single-copy genes in a range of different chromatin contexts throughout the genus Drosophila, despite contrasting structures and biological functions. Another recent study also shows diversity in chromosomal location of genes in 2L heterochromatin (Yasuhara et al. 2005), although in this case there appears to have been no movement of these more distal genes between chromosomal elements. These results underscore the general findings from genome-sequencing projects (Hoskins et al. 2002) that heterochromatic genes are not distinguished by possession of unique promoter sequences or biological functions. Dbp80 and RpL15 are located next to each other and deep within the heterochromatin of the left arm of chromosome 3 in D. melanogaster (element D), where they function in a genomic context that normally silences gene expression (Schulze et al. 2005). However, this arrangement is not conserved in other species. In D. virilis, a representative of the subgenus Drosophila, the genes are located on separate elements (Dbp80 on D and RpL15 on E) and different chromatin environments (DvDbp80 is euchromatic while DvRpL15 is heterochromatic). In D. pseudoobscura, which belongs to the subgenus Sophophora and occupies an intermediate evolutionary position between D. melanogaster and D. virilis, both genes are adjacent and located in the middle of the euchromatic arm comprising element E (D. pseudoobscura chromosome 2). The DNA sequence environment is repetitive, so these genes potentially reside in a portion of intercalary heterochromatin in this species. Comparison among these three species of Drosophila indicates that the deep heterochromatic location of these two genes in D. melanogaster is therefore not conserved on an evolutionary timescale.

Dbp80 and RpL15 show contrasting evolutionary dynamics with respect to gene structure:

This study suggests that the surrounding genomic environment does affect gene structure, although the effect of gene expansion in heterochromatin is subject to constraints on gene function. Dbp80 is a small gene with a single intron in the subgenus Drosophila, but is expanded with many introns in the subgenus Sophophora, while RpL15 maintains a conserved gene structure among all the examined species (Figure 4). There is some evidence suggesting that the expanded version of Dbp80 is ancestral, on the basis of the structure in An. gambiae, which, although separated from Drosophila by a quarter of a billion years, shares the position of all five of its introns with species from the Sophophoran subgenus. A more closely related outgroup, such as a representative of the subfamily Steganinae (e.g., Gitona bivisualiz, Remsen and O'Grady 2002), would provide greater resolution of the ancestral gene structure for Dbp80 for members of the genus Drosophila.

Expansion in the sizes of the introns in Dbp80 correlates with the surrounding content of repetitive sequences, yet RpL15 is impervious to this effect (see Figure 4 and Table 1). This difference is likely due to the contrasting biological functions that these genes encode and the fitness consequences that result from altering their structures. Dbp80 is a protein that belongs to a very large and diverse family of RNA helicases that exhibits great flexibility in gene structure (Boudet et al. 2001). Additionally, many RNA helicases have overlapping, possibly redundant, functions in RNA metabolism (de la Cruz et al. 1999), and this gene is not essential in D. melanogaster (Gatfield et al. 2001; Schulze et al. 2005) or in any other organism in which it has been tested to date (Kamath et al. 2003; Rollenhagen et al. 2004). Therefore, purifying selection on Dbp80 apparently allows for variety in its gene structure. RpL15, on the other hand, encodes an essential housekeeping function, required at high levels of expression at all times. Such genes have been shown to experience a strong selection pressure to remain small and easily processed (Castillo-Davis et al. 2002), which is consistent with the highly conserved structure for this gene among the examined species regardless of the surrounding environment.

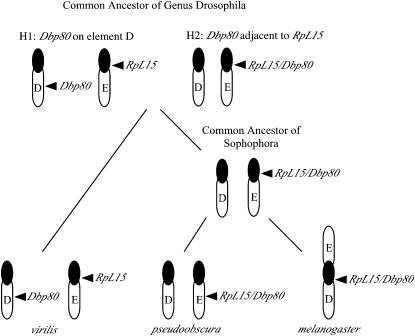

Model for interchromosomal relocation for Dbp80 and RpL15 in Drosophila:

Movement of genes between chromosomal elements of Drosophila is considered unusual, but has been reported for specific instances of genes belonging to multi-gene families (Ranz et al. 2003) and events of retrotransposition and pericentric inversion (Lemeunier and Ashburner 1976; Betran et al. 2002; Richards et al. 2005). A special case of interelement gene movement is also exemplified by the transfer of genes from the ancestral Y chromosome into the autosomal genome of D. pseudoobscura (Carvalho and Clark 2005). Despite these examples, interelement movement is not considered the norm. The inference of repeated interelement movements involving Dbp80 and RpL15 is therefore quite striking. Both are intact, single-copy genes, and their movements appear to be confined to elements D and E, which compose the metacentric chromosome 3 of D. melanogaster.

At least two instances of interelement movement are required to account for the different positions of Dbp80 and RpL15 in the three focal species (D. virilis, D. pseudoobscura, and D. melanogaster), and the other species provide a context for inferring the pattern of movement (Figure 6). A conserved set of genes flanks RpL15 in species representing both subgenera, and Dbp80 is a component of this association in most members of the subgenus Sophophora (Figure 5). On the other hand, a unique set of genes is present flanking Dbp80 in the subgenus Drosophila (D. mojavensis and D. virilis), where Dbp80 is not adjacent to RpL15, thus implicating an initial interelement movement of Dbp80 during the divergence of the two subgenera. The genes reside on separate elements in An. gambiae, but a 1:1 relationship does not exist between the chromosomal arms of An. gambiae and D. melanogaster (Zdobnov et al. 2002). The direction of the interelement movement in the genus Drosophila therefore cannot be resolved without an appropriate (more closely related) outgroup to infer the ancestral arrangement of Dbp80 and RpL15.

Figure 6.—

Model for the movement of Dbp80 and RpL15 throughout the genus Drosophila. At least two interelement movements must have taken place to explain the present locations of these genes in Drosophila. Evidence for the location of Dbp80 relative to RpL15 is lacking for the common ancestor of the genus Drosophila, so two hypotheses for the first relocation can be considered. Either both genes were located on separate elements in the common ancestor (H1) and Dbp80 moved adjacent to RpL15 in the common ancestor of the subgenus Sophophora, or the genes were adjacent (H2) and Dbp80 moved away from RpL15 in the subgenus Drosophila consistent with the position in the genome of D. virilis. Further relocation events take place in the subgenus Sophophora. The ancestral location of RpL15 in this subgenus is apparently centromeric, but it has moved to the middle of element E in D. pseudoobscura, possibly defining a region of intercalary heterochromatin. Following the fusion of elements D and E in the melanogaster lineage, the region containing RpL15 and Dbp80 moved between these elements by a pericentric inversion.

If these genes were located on separate chromosomal elements in the common ancestor of the genus Drosophila (H1 in Figure 6), then Dbp80 moved adjacent to RpL15 in the common ancestor of the subgenus Sophophora. The movement of Dbp80 is not coupled with changes in its structure in this scenario, since the relocated gene has retained its ancestral (expanded) form. Alternatively, the two genes were adjacent in the common ancestor of the genus Drosophila (H2 in Figure 6), in which case Dbp80 has moved from element E to element D in the lineage leading to D. virilis and D. mojavensis. Since our analysis suggests that the ancestral form of Dbp80 was expanded with many introns, this hypothesized movement could be coupled with intron loss, as the gene is vastly reduced in the subgenus Drosophila (D. virilis and D. mojavensis). Retrotransposition is a plausible mechanism that couples gene movement with the removal of introns; however, a single intron is present in the compacted version of Dbp80. In this regard it is of interest to note that the position of this intron is conserved not only among species from Drosophila, but also in the mammalian homologs [between exons 7 and 8: see http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sutils/evv.cgi?contig=NT_010498.15&gene=DDX19&lid=11269, presenting evidence for human DBP80 (DDX19) gene structure] although not in Anopheles (see Figure 4), suggesting that it may contain vital regulatory sequences. Thus, the compacted version of Dbp80 present in the D. virilis genome could be an example of a rare exception where an intron has been retained during a retrotransposition event.

A second interelement movement is also necessary to account for the repositioning of the region, including both RpL15 and Dbp80 between element E (as in D. pseudoobscura) and element D (as in D. melanogaster) within the subgenus Sophophora. The position of RpL15 in the centromeric heterochromatin of D. melanogaster and D. virilis indicates that this is the ancestral location. A paracentric inversion is the simplest explanation for the relocation of both genes into the middle of element E in D. pseudoobscura, thus suggesting a possible route in the formation of intercalary heterochromatin. In D. melanogaster, a centromeric fusion between elements D and E, followed by a pericentric inversion, would cause the relocation of Dbp80 and RpL15 from element E to D in D. melanogaster. There is evidence for this course of events in D. melanogaster. Genes from elements D and E of D. melanogaster are present flanking RpL15 in the other species, which retrospectively reflects the redistribution of genes between these elements. This creates an impression of mosaicism in genomic regions associated with RpL15 across these lineages, but, in reality, the only true mosaic is D. melanogaster. In this species, genes formerly present on D and E have become redistributed as a result of a pericentric inversion having occurred after the fusion of these elements

The repetitive sequence context predominantly associated with both genes may also have facilitated the inferred movements: ectopic recombination between repetitive elements is not an unusual event and indeed has been exploited by geneticists for experimental purposes (Gray et al. 1996). The Ulysses element that resides downstream of Dbp80 in D. virilis might have enabled just such a natural event involving a segment of euchromatin. The presence of this element is polymorphic (for instance, it is not present at this location in the strain sequenced by Agencourt) and may coincide in this position with an inversion breakpoint in the chromosome that can be identified in different strains of D. virilis (Evgen'ev et al. 2000).

Chromosomal elements are dynamic genomic structures—caution advised for annotation:

While gene content of the euchromatic chromosomal arms for the most part appears to be conserved among Drosophila species, our analysis of the evolutionary history of Dbp80 and RpL15 demonstrates that a different picture may arise for genes contained within regions of centromeric heterochromatin. The static view of the chromosomal elements of Drosophila clearly must be applied cautiously with respect to genes residing in centromeric regions, especially in comparisons with the extensively annotated D. melanogaster genome, which has undergone two centric fusions involving four (of a total of six) chromosomal elements. This study implicates relocation of genes on chromosome 3 by a pericentric inversion, and the analysis of the genome sequence of D. pseudoobscura indicates the same has occurred for chromosome 2 (Richards et al. 2005). Because of the dynamic repositioning of the two genes studied here, a wider examination of additional heterochromatic loci is needed to elucidate the constraints on these regions of the genome. This study also demonstrates that a full understanding of the genomic location of these genes requires experimental confirmation by in situ hybridization, as the standard assumptions (genes confined to Muller's elements) developed for conserved euchromatic genes do not apply to genes that have relocated into and out of heterochromatin.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Andy Beckenbach and Wyatt Anderson for interpretation of D. pseudoobscura polytene chromosomes and to Horst Kress for interpretation of D. virilis polytene chromosomes. We also thank Giacomo Cavalli, Jerome Desjardins, and Frederic Bantignies for generous assistance with polytene chromosome analysis and imaging. We are grateful to Agencourt Bioscience, the Human Genome Sequencing Center at Baylor College of Medicine, the J. Craig Venter Institute, the Genome Sequencing Center at Washington University, and the National Center for Biotechnology Information for the availability of the sequence data. This work was supported by a National Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) Canada Discovery grant to B.M.H., an NSERC Canada Postgraduate Scholarship B to S.R.S., and a National Science Foundation grant DEB-0420399 to B.F.M.

References

- Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang et al., 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avramova, Z. V., 2002. Heterochromatin in animals and plants: similarities and differences. Plant Physiol. 129: 40–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat, A., K. Szick-Miranda, I. Chang, R. Guyot, G. Blanc et al., 2001. The organization of cytoplasmic ribosomal protein genes in the Arabidopsis genome. Plant Physiol. 127: 398–415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betran, E., K. Thornton and M. Long, 2002. Retroposed new genes out of the X in Drosophila. Genome Res. 12: 1854–1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudet, N., S. Aubourg, C. Toffano-Nioche, M. Kreis and A. Lecharny, 2001. Evolution of intron-exon structure of DEAD helicase family genes in Arabidopsis, Caenorhabditis, and Drosophila. Genome Res. 11: 2101–2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, A. B., and A. G. Clark, 2005. Y chromosome of D. pseudoobscura is not homologous to the ancestral Drosophila Y. Science 307: 108–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Davis, C. I., S. L. Mekhedov, D. L. Hartl, E. V. Koonin and F. A. Kondrashov, 2002. Selection for short introns in highly expressed genes. Nat. Genet. 31: 415–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg, N. J., B. M. Honda, I. P. Whitehead, T. A. Grigliatti, B. Wakimoto et al., 1998. Suppressors of position-effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster affect expression of the heterochromatic gene light in the absence of a chromosome rearrangement. Genome 41(4): 495–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulthard, A. B., D. F. Eberl, C. B. Sharp and A. J. Hilliker, 2003. Genetic analysis of the second chromosome centromeric heterochromatin of Drosophila melanogaster. Genome 46(3): 343–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, J. M., 2005. Heterochromatin—many flavours, common themes. BioEssays 27(1): 17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz, J., D. Kressler and P. Linder, 1999. Unwinding RNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: DEAD-box proteins and related families. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24: 192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, R. H., D. G. Holm, K. R. Morin and B. M. Honda, 1990. a Identifying a single copy DNA sequence associated with the expression of a heterochromatic gene, the light locus of Drosophila melanogaster. Genome 33: 405–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, R. H., B. Bingham and B. T. Wakimoto, 1990. b The organization and expression of the light gene, a heterochromatic gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 125: 129–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitri, P., N. Junakovic and B. Arca, 2003. Colonization of heterochromatic genes by transposable elements in Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20(4): 503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitri, P., N. Corradini, F. Rossi and F. Verni, 2005. The paradox of functional heterochromatin. BioEssays 27(1): 29–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domazet-Loso, T., and D. Tautz, 2003. An evolutionary analysis of orphan genes in Drosophila. Genome Res. 13: 2213–2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl, D. F., B. J. Duyf and A. J. Hilliker, 1993. The role of heterochromatin in the expression of a heterochromatic gene, the rolled locus of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 134: 277–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen, J. A., 1998. A phylogenomic study of the MutS family of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 26(18): 4291–4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evgen'ev, M. B., H. Zelentsova, H. Poluectova, G. T. Lyozin, V. Veleikodvorskaja et al., 2000. Mobile elements and chromosomal evolution in the virilis group of Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97(21): 11337–11342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, K. A., D. A. Sinclair, S. R. Schulze, M. Syrzycka and B. M. Honda, 2005. A genetic and molecular profile of third chromosome centric heterochromatin in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome 48: 571–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatfield, D., H. Le Hir, C. Schmitt, I. C. Braun, T. Köcher et al., 2001. The DExH/D box protein HEL/UAP56 is essential for mRNA nuclear export in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 11: 1716–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Y. H. M., M. M. Tanaka and J. A. Sved, 1996. P-element-induced recombination in Drosophila melanogaster: hybrid element insertion. Genetics 144: 1601–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, S. I., and S. C. R. Elgin, 2002. Heterochromatin: new possibilities for the inheritance of structure. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12: 178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan, N., and R. P. Perry, 1990. Functional dissection of a mouse ribosomal protein promoter: significance of the polypyrimidine initiator and an element in the TATA-box region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87: 1526–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliker, A. J., 1976. Genetic analysis of the centromeric heterochromatin of chromosome 2 of Drosophila melanogaster: deficiency mapping of EMS induced lethal complementation groups. Genetics 83: 765–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliker, A. J., and D. G. Holm, 1975. Genetic analysis of the proximal region of chromosome 2 of Drosophila melanogaster. I. Detachment products of compound autosomes. Genetics 81: 705–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmquist, G., 1975. Organisation and evolution of Drosophila virilis heterochromatin. Nature 257: 503–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, R. A., G. M. Subramanian, A. Halpern, G. G. Sutton, R. Charlab et al., 2002. The genome sequence of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Science 298: 129–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, R. A., C. D. Smith, J. W. Carlson, A. B. Carvalho, A. Halpern et al., 2002. Heterochromatic sequences in a Drosophila whole-genome shot-gun assembly. Genome Biol. 3(12): research00851–008516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jowett, T., 1998. Preparation of nucleic acids, pp. 347–371 in Drosophila: A Practical Approach, edited by D. B. Roberts. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Kamath, R. S., A. G. Fraser, Y. Dong, G. Poulin, R. Durbin et al., 2003. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421: 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress, H., 1993. The salivary gland chromosomes of Drosophila virilis: a cytological map, pattern of transcription and aspects of chromosome evolution. Chromosoma 102: 734–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemeunier, F., and M. A. Ashburner, 1976. Relationships within the melanogaster species subgroup of the genus Drosophila (Sophophora). II. Phylogenetic relationships between six species based upon polytene chromosome banding sequences. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 193: 275–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S., D. Avni, N. Hariharan, R. P. Perry and O. Meyuhas, 1991. Oligopyrimidine tract at the 5′ end of mammalian ribosomal protein mRNAs is required for their translational control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88: 3319–3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, B. Y., P. C. R. Emtage, B. J. Duyf, A. J. Hilliker and J. C. Eissenberg, 2000. Heterochromatin protein 1 is required for the normal expression of two heterochromatic genes in Drosophila. Genetics 155: 699–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant, G. E., and D. G. Holm, 1988. a Genetic analysis of the heterochromatin of chromosome 3 in Drosophila melanogaster. I. Products of compound-autosome detachment. Genetics 120: 503–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant, G. E., and D. G. Holm, 1988. b Genetic analysis of the heterochromatin of chromosome 3 in Drosophila melanogaster. II. Vital loci identified through EMS mutagenesis. Genetics 120: 519–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardis, E., J. McPherson, R. Martienssen, R. K. Wilson and W. R. McCombie, 2002. What is finished and why does it matter? Genome Res. 12: 669–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, H. J., 1940. Bearings of the Drosophila work on systematics. New Syst. 185–268.

- Papaceit, M., and E. Juan, 1998. Fate of dot chromosome genes in Drosophila willistoni and Scaptodrosophila lebanonensis determined by in situ hybridization. Chromosome Res. 6: 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimpinelli, S., and B. T. Wakimoto, 2003. Expanding the boundaries of heterochromatin. Genetica 117: 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimpinelli, S., S. Bonaccorsi, L. Fanti and M. Gatti, 2000. Preparation and analysis of Drosophila mitotic chromosomes, pp. 3–23 in Drosophila Protocols, edited by W. Sullivan, M. Ashburner and R. S. Hawley. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Powell, J. R., 1997. Progress and Prospects in Evolutionary Biology: The Drosophila Model. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Ranz, J. M., J. González, F. Casals and A. Ruiz, 2003. Low occurrence of gene transposition events during the evolution of the genus Drosophila. Evolution 57: 1325–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remsen, J., and P. O'Grady, 2002. Phylogeny of Drosophilinae (Diptera: Drosophilidae), with comments on combined analysis and character support. Mol. Phylogent. Evol. 24: 249–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards, S., Y. Liu, B. R. Bettencourt, P. Hradecky, S. Letovsky et al., 2005. Comparative genome sequencing of Drosophila pseudoobscura: chromosomal, gene, and cis-element evolution. Genome Res. 15: 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risinger, C., D. L. Deitcher, I. Lundell, T. L. Schwarz and D. Larhammer, 1997. Complex gene organization of synaptic protein SNAP-25 in Drosophila melanogaster. Gene 194: 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollenhagen, C., C. A. Hodge and C. N. Cole, 2004. The nuclear pore complex and the DEAD box protein Rat8p/Dbp5p have nonessential features which appear to facilitate mRNA export following heat shock. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 4869–4879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch and T. Maniatis, 1989. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Ed. 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Schulze, S. R., D. A. R. Sinclair, E. Silva, K. A. Fitzpatrick, M. Singh et al., 2001. Essential genes in proximal 3L heterochromatin of Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Gen. Genet. 264: 782–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, S. R., D. A. Sinclair, K. A. Fitzpatrick and B. M. Honda, 2005. A genetic and molecular characterization of two proximal heterochromatic genes on chromosome 3 of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 169: 2165–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, D. A., S. Schulze, E. Silva, K. A. Fitzpatrick and B. M. Honda, 2000. Essential genes in autosomal heterochromatin of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetica 109(1–2): 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snay-Hodge, C. A., H. V. Colot, A. L. Goldstein and C. N. Cole, 1998. Dbp5p/Rat8p is a yeast nuclear pore-associated DEAD-box protein essential for RNA export. EMBO J. 17(9): 2663–2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins and T. J. Gibson, 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thummel, C., 1993. Compilation of Drosophila cDNA and genomic libraries. Dros. Inf. Serv. 72: 180–183. [Google Scholar]

- Tobari, Y. N., 1993. Drosophila ananassae: Genetical and Biological Aspects. Japan Scientific Societies Press, Tokyo.

- Tulin, A., D. Stewart and A. C. Spradling, 2002. The Drosophila heterochromatic gene encoding poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) is required to modulate chromatin structure during development. Genes Dev. 16: 2108–2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, J., C. P. Vieira, D. L. Hartl and E. R. Lozovskaya, 1997. A framework physical map of Drosophila virilis based on P1 clones: applications in genome evolution. Chromosoma 106: 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakimoto, B. T., and M. G. Hearn, 1990. The effects of chromosome rearrangements on the expression of heterochromatic genes in chromosome 2L of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 125(1): 141–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren, W. D., E. Lin, T. V. Nheu, G. R. Hime and M. J. McKay, 2000. Drad21, a Drosophila rad21 homologue expressed in S-phase cells. Gene 250: 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, M., 1982. Evolution of the repleta group, pp. 61–139 in The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila, Vol. 3b, edited by M. Ashburner, H. L. Carson and J. N. Thompson. Academic Press, New York.

- Yasuhara, J. C., C. H. Decrease and B. T. Wakimoto, 2005. Evolution of heterochromatic genes in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102(31): 10958–10963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdobnov, E. M., C. Von Mering, I. Letunic, D. Torrents, M. Suyama et al., 2002. Comparative genome and proteome analysis of Anopheles gambiae and Drosophila melanogaster. Science 298: 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhimulev, I. F., and E. S. Belyaeva, 2003. Intercalary heterochromatin and genetic silencing. BioEssays 25: 1040–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]