Abstract

Most plant disease resistance (R) genes known today encode proteins with a central nucleotide binding site (NBS) and a C-terminal Leu-rich repeat (LRR) domain. The NBS contains three ATP/GTP binding motifs known as the kinase-1a or P-loop, kinase-2, and kinase-3a motifs. In this article, we show that the NBS of R proteins forms a functional nucleotide binding pocket. The N-terminal halves of two tomato R proteins, I-2 conferring resistance to Fusarium oxysporum and Mi-1 conferring resistance to root-knot nematodes and potato aphids, were produced as glutathione S-transferase fusions in Escherichia coli. In a filter binding assay, purified I-2 was found to bind ATP rather than other nucleoside triphosphates. ATP binding appeared to be fully dependent on the presence of a divalent cation. A mutant I-2 protein containing a mutation in the P-loop showed a strongly reduced ATP binding capacity. Thin layer chromatography revealed that both I-2 and Mi-1 exerted ATPase activity. Based on the strong conservation of NBS domains in R proteins of the NBS-LRR class, we propose that they all are capable of binding and hydrolyzing ATP.

INTRODUCTION

Plants have to defend themselves against a wide range of pathogenic organisms. One way to achieve this is through the recognition of “nonself” components. The plant's ability to recognize different races of the same pathogen involves the presence of race-specific resistance genes (R genes). This R gene–mediated resistance can be considered as the innate immunity of the plant (Fluhr, 2001) and is achieved by triggering an array of defense responses (Dangl and Jones, 2001). How R proteins trigger the signal transduction pathway(s) leading to plant defense is not yet understood. The largest class of R genes encodes proteins that have a variable N terminus, a conserved central domain predicted to function as a nucleotide binding site (NBS), and a variable number of Leu-rich repeats (LRRs) at the C terminus. This group of R proteins often is referred to as the NBS-LRR class. The C-terminal LRR domain is shared by many other proteins, in which it functions as a region for protein–protein interactions and peptide-ligand binding (Jones and Jones, 1997). The LRR domain of R proteins might contribute to the recognition of diverse pathogen-derived ligands.

The NBS contains three peptide motifs that are critical for nucleotide binding in many ATP/GTP binding proteins (Traut, 1994). In these proteins, all three motifs function in the interaction with the nucleotide. The first is the kinase-1a motif, also known as the P-loop or Walker A motif. It forms a Gly-rich flexible loop containing an invariant Lys residue involved in binding the phosphates of the nucleotide (Walker et al., 1982; Saraste et al., 1990; Traut, 1994). Mutation of this residue frequently results in decreased nucleotide binding capacity (Hishida et al., 1999, and references therein). The kinase-2 or Walker B motif has an invariant Asp that coordinates the divalent metal ion required for phosphotransfer reactions (e.g., Mg2+ of Mg-ATP). A third, less conserved, motif is the kinase-3a motif, which is involved in binding the purine base or the pentose of the nucleotide (Traut, 1994). Mutational analyses of the R genes N, RPS2, and RPM1 have shown that at least the predicted P-loop and kinase-2 motifs are indispensable for their biological function (Dinesh-Kumar et al., 2000; Tao et al., 2000; Tornero et al., 2002). However, the question remains whether the putative nucleotide binding site of R proteins really does form a functional nucleotide binding pocket.

Regulation in signaling processes often occurs by binding and hydrolysis of a nucleotide triphosphate. Classic examples of signal transduction proteins that can bind and hydrolyze nucleotides are the members of the GTPase superfamily. These proteins function as molecular switches in signaling pathways involved in very diverse cellular processes (reviewed by Bourne et al., 1990; Macara et al., 1996). Apaf-1 is an example of a protein that binds adenine nucleotides for regulatory purposes in signaling and plays a critical role in the induction of apoptosis in mammals (Zou et al., 1997). It contains a C-terminal domain with WD-40 repeats and a central NBS. In the presence of cytochrome c, binding of ATP or deoxy-ATP (dATP) to the NBS leads to the formation of a multimolecular aggregate called apoptosome (Saleh et al., 1999; Jiang and Wang, 2000). CED-4 is a functional homolog of Apaf-1 in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and fulfills a similar role in apoptosis. Although it has been shown that CED-4 is able to bind ATP, it is not clear whether binding triggers apoptosome formation, as it does with Apaf-1 (Seiffert et al., 2002). However, because mutations in the nucleotide binding motifs lead to loss of function, nucleotide binding to CED-4 is important for the initiation of apoptosis as well (Chinnaiyan et al., 1997; Yang et al., 1998).

The NBS region of Apaf-1 is highly similar to the nucleotide binding domain of CED-4 and, strikingly, also to the NBS region of many plant R proteins. The region of homology contains not only the three motifs involved in nucleotide binding but additional motifs as well (van der Biezen and Jones, 1998; Aravind et al., 1999). This extended region of homology is referred to as the NB-ARC domain. The strong conservation of this domain suggests similarity of function. As a first step in our investigation, we addressed the questions of whether the NBS of R proteins represents a genuine nucleotide binding pocket and whether bound nucleotides can be hydrolyzed. For this purpose, NBS-containing parts of the tomato R genes I-2 and Mi-1 were cloned into an expression vector to produce recombinant proteins in Esche-richia coli. I-2 confers resistance against race 2 isolates of the soil-borne pathogenic fungus Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici (Simons et al., 1998), and Mi-1 confers resistance to both the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita and the potato aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae (Milligan et al., 1998; Rossi et al., 1998; Vos et al., 1998). Purification of recombinant R proteins from E. coli allowed us to examine nucleotide binding capacity and ATPase activity in vitro.

RESULTS

Production of I-2 in E. coli

Based on amino acid sequence homology, the I-2 protein has the potential to bind nucleotides. To investigate its nucleotide binding capacity, we set out to purify I-2. In tomato, I-2 is expressed predominantly at low levels in xylem parenchyma cells. In addition to I-2 itself, several homologs also are expressed in these plants (Mes et al., 2000). Therefore, wild-type plants are inappropriate as source material for the purification of endogenous I-2. Attempts to constitutively express tagged I-2 under the control of the 35S promoter of Cauliflower mosaic virus in transgenic tomato were unsuccessful because plants showing high I-2 expression levels were never obtained (data not shown). Likewise, constitutive and inducible expression of tagged I-2 in a tomato cell suspension did not result in the production of detectable levels of I-2 (data not shown). Therefore, we chose to produce recombinant I-2 protein in heterologous expression systems. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, full-length I-2 protein could be produced (data not shown), but expression levels were insufficient for purification. This prompted us to switch to a bacterial expression system. Full-length I-2 coding sequence was cloned into expression vector pGEX-KG as a translational fusion with glutathione S-transferase (GST) and transformed into E. coli strain BL21 (referred to as I-2F; Figure 1A). Transformants were grown and protein production was induced as described in Methods. Total lysates of E. coli expressing either I-2F or GST only were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. No obvious differences in the protein patterns of the two lysates were observed, except for the GST band in the empty vector control (Figure 2A, lanes 1 and 2). Upon immunostaining with anti-GST antibodies (Figure 2A, lanes 5 and 6), very little full-length fusion protein of 172 kD was detected. To exclude the possibility that the GST tag was removed post-translationally from the recombinant I-2F protein, blots were probed with antibodies raised against a synthetic peptide corresponding to amino acids 137 to 145 of I-2. The lack of cross-reactivity of these antibodies with endogenous E. coli proteins (Figure 2A, lane 10) indicates that the antibodies are specific for I-2. Immunostaining with both the GST- and I-2–specific antibodies (Figure 2A, lanes 5 and 9) detected predominantly polypeptides that were smaller than full-length I-2 product, suggesting instability of the full-length product or premature translation termination.

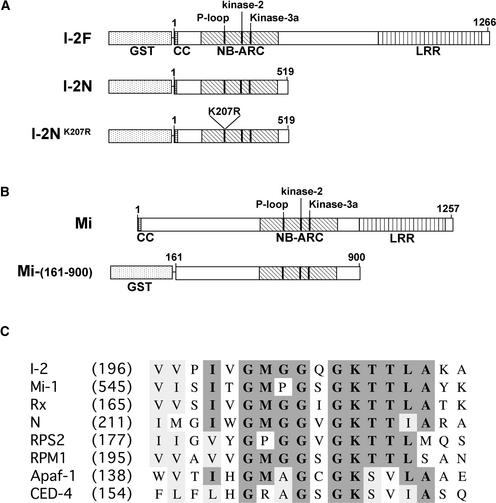

Figure 1.

Scheme of I-2 and Mi-1 Recombinant Proteins Used in This Study.

(A) For expression in E. coli, full-length I-2 (amino acids 1 to 1266) and the N-terminal part of I-2 (amino acids 1 to 519) were fused N terminally to GST (I-2F and I-2N, respectively). I-2NK207R contains a substitution of Lys-207 to Arg in the P-loop. CC, coiled-coil domain.

(B) Mi-(161-900), the part of Mi-1 containing the NB-ARC, fused N terminally to GST.

(C) Comparison of P-loop regions of R proteins and apoptosis-related proteins discussed in the text. Numbers in parentheses indicate the positions in the full-length proteins of the first residues shown for each protein.

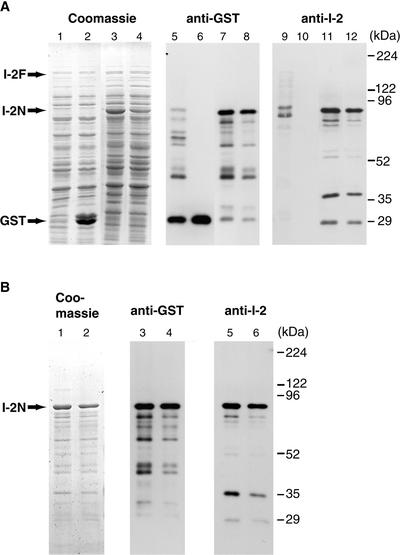

Figure 2.

Production and Purification of GST–I-2 Fusion Proteins.

I-2F, I-2N, and I-2NK207R were produced as GST fusion proteins in E. coli and purified as described in Methods.

(A) Total protein of isopropylthio-β-galactoside–induced E. coli lysates containing I-2F (lanes 1, 5, and 9), vector-only control (lanes 2, 6 and 10), I-2N (lanes 3, 7, and 11), and I-2NK207R (lanes 4, 8, and 12) on SDS–polyacrylamide gels stained with Coomassie blue (left panel) or visualized by immunoblotting with either anti-GST antibodies (middle panel) or anti-I-2 antiserum (right panel).

(B) Purified and refolded fractions of I-2N (lanes 1, 3, and 5) and I-2NK207R (lanes 2, 4, and 6) on SDS–polyacrylamide gels stained with Coomassie blue (left panel) or visualized by immunoblotting with either anti-GST antibodies (middle panel) or anti-I-2 antiserum (right panel).

Next, the I-2 sequence encoding amino acids 1 to 519, containing the entire NB-ARC domain (referred to as I-2N; Figure 1A), was cloned into pGEX-KG and expressed in E. coli. A strong accumulation of a fusion protein of the predicted molecular mass of 88 kD was observed upon induction by isopropylthio-β-galactoside (Figure 2A, lane 3). In a control lysate, a protein of this size was absent (Figure 2A, lane 2). Immunoblot analysis of the lysates with either anti-GST antibodies (Figure 2A, lane 7) or anti-I-2 antiserum (Figure 2A, lane 11) confirmed that the 88-kD protein band represents the I-2–GST fusion product.

A third construct was made encoding the same GST fusion except for the substitution of the Lys residue at position 207 with an Arg residue (referred to as I-2NK207R; Figure 1A). This Lys residue is located in the P-loop motif (Figure 1C), and substitution of this residue usually results in a loss of function. The mutant I-2NK207R protein accumulated in a manner similar to the wild-type I-2N protein in E. coli (Figure 2A, lanes 4, 8, and 12).

Both fusion proteins were found to accumulate in inclusion bodies. Therefore, an inclusion body purification method was applied in which the aggregates were washed several times with a buffer containing 1% Triton X-100. Finally, inclusion bodies were solubilized at room temperature in buffer containing 8 M urea. The denaturant was removed by stepwise dialysis in the presence of 20% glycerol, promoting the refolding of I-2N and I-2NK207R. Figure 2B shows the samples after purification and refolding of I-2N (lanes 1, 3, and 5) and I-2NK207R (lanes 2, 4, and 6) on a stained SDS–polyacrylamide gel (left panel) or visualized by immunostaining with either anti-GST antibodies (middle panel) or anti-I-2 antiserum (right panel). As can be observed, smaller fusion protein–derived polypeptides were copurified. The banding patterns of immunoreactive proteins were similar in samples derived from E. coli expressing wild-type and mutant I-2 constructs.

I-2 Contains a Functional Nucleotide Binding Pocket

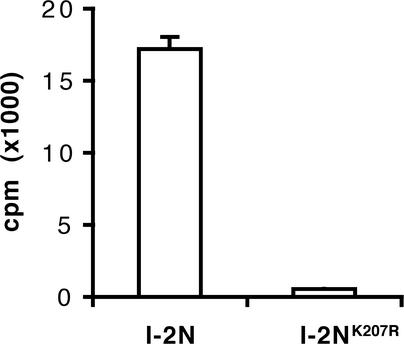

A filter binding assay was developed using refolded I-2N and I-2NK207R to investigate the nucleotide binding activity of I-2. Proteins were incubated on ice in the presence of α-32P-ATP. After 15 min, the incubation mixtures were spotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride filters and washed extensively with ice-cold buffer, and the radioactivity retained on the filters by I-2 was measured. Figure 3 shows that wild-type I-2N retained radioactivity on filters, suggesting that the protein binds ATP. By contrast, I-2NK207R containing the P-loop mutation retained little radioactivity (3% of I-2N). This result strongly suggests that I-2 contains a functional nucleotide triphosphate binding pocket able to bind ATP. The low amount of radioactivity retained by I-2NK207R reflects a residual binding capacity rather than aspecific binding (see below).

Figure 3.

Binding of ATP to I-2N and I-2NK207R.

I-2N and I-2NK207R (1.5 μM) were incubated with 0.1 μM α-32P-ATP (4.4 × 105 cpm/pmol). The radioactivity bound to the proteins was measured in a filter binding assay as described in Methods.

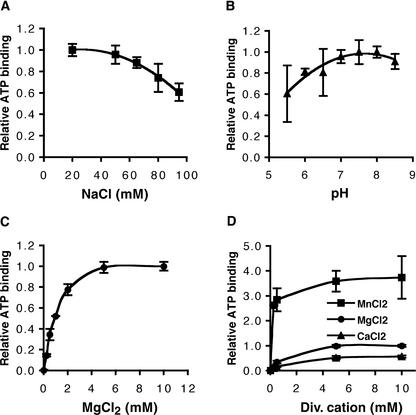

The binding assays described above were performed in buffer containing 50 mM NaCl and 5 mM MgCl2 at pH 7.5. Changing the NaCl concentration in a range between 20 and 95 mM did not affect ATP binding drastically (Figure 4A), nor did changing the pH in the range 5.5 to 8.5 (Figure 4B). Because of the presence of a kinase-2 motif in the NBS of I-2, nucleotide binding is expected to be dependent on the presence of divalent cations. Indeed, ATP binding was found to be affected by the Mg2+ concentration. Omitting Mg2+ from the incubation mixture reduced ATP binding to background levels (Figure 4C). With increasing Mg2+ concentrations, an increase in binding activity was observed, reaching a maximum at ∼5 mM (Figure 4C). Mg2+ could be replaced by other divalent cations, such as Mn2+ or Ca2+ (Figure 4D). In the presence of Mn2+, ATP binding was approximately four times higher relative to the binding in the presence of Mg2+, whereas binding was reduced approximately twofold in the presence of Ca2+ (Figure 4D). This result shows that the presence of a divalent cation is absolutely required for the nucleotide binding of I-2, as has been found for other ATP binding proteins (Traut, 1994).

Figure 4.

Influence of Ion Concentrations and pH on ATP Binding of I-2N.

α-32P-ATP binding was measured in a filter binding assay as described in Methods.

(A) to (C) The maximal amount of α-32P-ATP bound was set to 1.

(A) I-2N (1 μM) was incubated with 0.07 μM α-32P-ATP (6.3 × 105 cpm/pmol) in the standard reaction mixture except for a variable NaCl concentration.

(B) I-2N (1.5 μM) was incubated with 0.1 μM α-32P-ATP (4.3 × 105 cpm/pmol) in the standard reaction mixture except for a variable pH.

(C) I-2N (0.8 μM) was incubated with 0.2 μM α-32P-ATP (2.1 × 105 cpm/pmol) in the standard reaction mixture except for a variable MgCl2 concentration and the absence of DTT and EDTA.

(D) I-2N (0.8 μM) was incubated with 0.2 μM α-32P-ATP (2.1 × 105 cpm/pmol) in the standard reaction mixture except for variable concentrations of the divalent (Div.) cations of MgCl2, MnCl2, or CaCl2. The maximal amount of α-32P-ATP bound in presence of MgCl2 was set to 1.

I-2 Binds Specifically to Adenosine Nucleotides

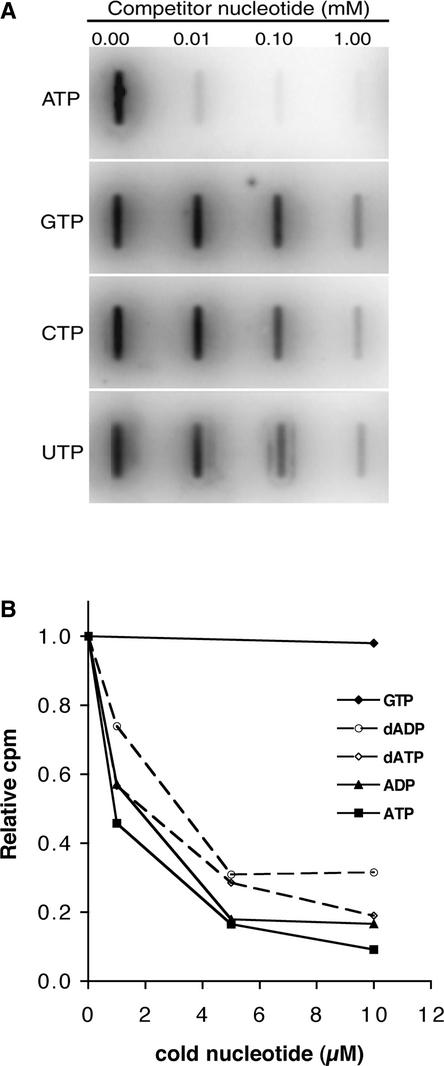

To determine whether I-2 shows specificity in nucleotide binding, competition experiments were performed. First, α-32P-ATP was mixed with increasing amounts of a cold competitor, nucleoside triphosphate. Figure 5A shows that ATP competed much more effectively for α-32P-ATP binding than GTP, CTP, and UTP. Quantitation of the signal revealed that in the presence of 10 μM ATP, binding of α-32P-ATP was reduced by >90%, whereas binding was reduced very little in the presence of 10 μM CTP, GTP, or UTP. These experiments demonstrate a clear binding specificity of the I-2 protein for ATP in vitro. When α-32P-ATP was mixed with increasing amounts of ADP, dATP, or dADP, strong competition in binding was observed in all cases. At 10 μM, these nucleotides reduced the binding of α-32P-ATP to I2-N by 70 to 90%, whereas the presence of GTP at the same concentration had little effect (Figure 5B). This finding demonstrates that I-2 has affinity not only for ATP but for ADP, dATP, and dADP as well.

Figure 5.

I-2N Binds Specifically Adenine Nucleotides.

I-2N (2.5 μM) was incubated with 0.06 μM α-32P-ATP (7.7 × 105 cpm/pmol) as described in Methods. α-32P-ATP was premixed with various amounts of the indicated cold nucleotides.

(A) Reactions were vacuum filtrated using a slot-blot apparatus and a polyvinylidene difluoride sheet. Radioactivity was visualized by phosphorimaging.

(B) The amount of α-32P-ATP bound to I-2N was measured in a filter binding assay as described in Methods.

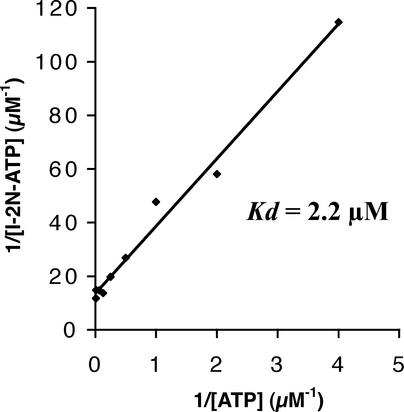

To quantify the affinity of the nucleotide binding pocket of I-2 for ATP, we performed a filter binding assay with I-2N and increasing amounts of α-32P-ATP. After plotting the amount of ATP bound against the ATP concentration, a clear saturation curve was obtained (Figure 6). From these data, a Kd value of 2.2 μM was calculated using a Scatchard plot.

Figure 6.

Kd Measurement of the I-2N–ATP Complex.

I-2N (1.5 μM) was incubated with increasing amounts of α-32P-ATP (3.4 × 103 to 1.8 × 105 cpm/pmol) in the standard reaction mixture. The radioactivity of α-32P-ATP bound to I-2N was measured as described in Methods. Kd was calculated using a Scatchard plot.

I-2 Exerts ATPase Activity

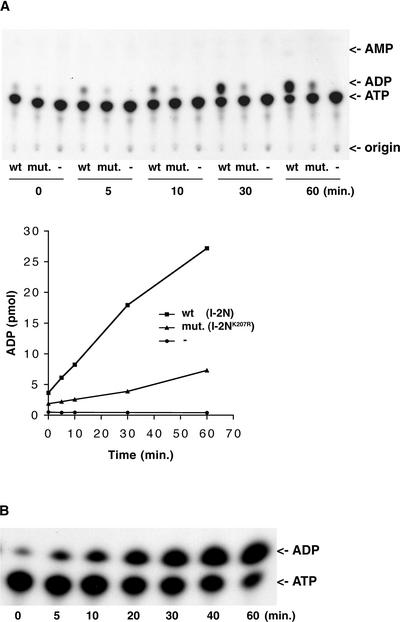

To determine whether I-2 is capable of hydrolyzing ATP, I-2N and I-2NK207R were incubated with α-32P-ATP at room temperature. Samples were taken at different time points and analyzed by thin layer chromatography to separate α-32P-ADP and α-32P-AMP from α-32P-ATP. A thin layer chromatography autoradiogram (Figure 7A) shows that in the presence of I2-N, the amount of α-32P-ADP increased in time at the cost of the amount of α-32P-ATP. In the absence of I-2, no α-32P-ADP was generated. In the presence of I-2NK207R, ATP hydrolysis occurred to a lesser extent (30% of the wild type level). From these results, we conclude that the ADP formed in the reaction with wild-type I-2 is attributable to specific hydrolysis of ATP by I-2N. The detection of ATPase activity in I-2NK207R suggests that the mutated NBS still has residual binding activity (Figure 3).

Figure 7.

I-2 and Mi-1 Exhibit ATPase Activity.

I-2N (1.9 μM; wild type [wt]) and I-2NK207R (1.9 μM; mutant [mut.]), together with a buffer control (A) or 1.5 μM Mi-(161-900) (B), were incubated with 5.0 μM α-32P-ATP (4.4 × 104 cpm/pmol). Reactions were subjected to thin layer chromatography to detect the production of α-32P-ADP with autoradiography and quantitated by phosphorimaging as described in Methods.

ATPase Activity of Another NBS-LRR Protein, Mi-1

To investigate whether, in analogy with I-2, other R proteins of the NBS-LRR class have ATPase activity as well, we examined another tomato R protein with a structure similar to that of I-2, Mi-1 (Figure 1B). A translational GST fusion construct encoding the complete NB-ARC domain of Mi-1 was used for protein production in E. coli [referred to as Mi-(161-900); Figure 1B]. The fusion protein was purified from inclusion bodies and refolded using the same procedures used for I-2. Refolded Mi-(161-900) was used in the ATPase assay with α-32P-ATP. Figure 7B shows that, like I-2, Mi-1 is a functional ATPase.

DISCUSSION

Most R genes known today encode proteins with a central region containing peptide motifs typical of the NBS found in many ATP/GTP binding proteins. Here, we show that the putative NBS of two of these R proteins, I-2 and Mi-1, are able to bind ATP and exert ATPase activity. Based on the conservation of the NBS domain in other functional R proteins of the NBS-LRR class (Meyers et al., 1999; Pan et al., 2000), it is very likely that ATP binding and ATPase activity are general features of this group of proteins. Mutational analysis of the R genes N, RPS2, and RPM1 have shown that the predicted P-loop (Figure 1C) and kinase-2 motifs are essential for their function in plant defense signaling (Dinesh-Kumar et al., 2000; Tao et al., 2000; Tornero et al., 2002). We have shown that substitution of the invariant Lys in the P-loop motif of I-2 (Figure 1C) strongly reduces both ATP binding and hydrolysis. Because such an effect has been reported for many other nucleotide binding proteins containing a P-loop motif (Rivas et al., 1997; Mizushima et al., 1998; Hishida et al., 1999, and references therein), it is likely that substitution of this residue in RPS2 and N leads to loss-of-function alleles as a result of reduced nucleotide binding capacity. Whether the P-loop mutation (K207R) in I-2 will result in a loss of biological function is not known.

Meyers and co-workers (1999) analyzed the NBS of 14 known R proteins and >400 homologs. They noted that the so-called G-4 region, which is characteristic of the GTPase superfamily, was absent in all sequences. Therefore, they suggested that R proteins would bind ATP rather than GTP. Our analysis of the nucleotide preference of recombinant I-2 shows that α-32P-ATP binding can be competed for efficiently by ATP but not by GTP or other nucleoside triphosphates (Figure 5A). This finding confirms the hypothesis that R proteins are ATP binding proteins. With most ATP/GTP binding proteins, the omission of divalent cations from the reaction not only abolishes hydrolysis but results in a decreased nucleotide binding capacity as well (Hishida et al., 1999; Rombel et al., 1999). Moreover, Mn2+ can substitute for Mg2+ in the function of several ATPases. In some cases, it even causes an increase in ATPase activity compared with Mg2+ (Koronakis et al., 1993). We observed similar behavior in recombinant I-2: both binding (Figure 4C) and ATPase activity (data not shown) were dependent on divalent cations. Also, Mn2+ could substitute for Mg2+ in the ATP binding assay (Figure 4D), giving rise to an approximately fourfold increase in ATP binding capacity. However, because the concentration of Mg2+ in the cytosol is much higher than that of Mn2+, it is likely that I-2 binds Mg-ATP in vivo.

The ATP binding capacity of the NBS of I-2 is shared with the homologous NBS of Apaf-1 and CED-4 (Jiang and Wang, 2000; Seiffert et al., 2002). However, there are differences in nucleotide affinity. Apaf-1 has a fivefold higher affinity for dATP than for ATP (Jiang and Wang, 2000). Although I-2 has affinity for dATP, it is slightly lower than that for ATP (Figure 5B). CED-4 also has lower affinity for dATP, but the difference in this case is ∼100-fold (Seiffert et al., 2002). Also, Apaf-1 has absolutely no affinity for dADP, the hydrolysis product of dATP, whereas I-2 does have affinity for ADP and even for dADP (Figure 5B). In this respect, I-2 behaves more like CED-4, because the latter has affinity for ADP as well, although ∼100-fold less than for ATP. Despite these differences, it is clear that they all are nucleotide binding proteins with adenine specificity.

Significantly, we show that I-2 and Mi-1 are capable not only of ATP binding but also of hydrolyzing the bound nucleotide (Figures 7A and 7B). If Apaf-1 contains nucleotidase activity at all, it is very low. Alternatively, nucleotidase activity may be stimulated by a factor that has a function similar to that of GTPase-activating proteins in signaling mediated by small GTPases. It is not known whether CED-4 exerts ATPase activity.

The region of homology in the central parts of Apaf-1, CED-4, and R proteins of the NBS-LRR class is not confined to the NBS but extends C terminally and is referred to as the NB-ARC domain (van der Biezen and Jones, 1998; Aravind et al., 1999). The potential of Apaf-1 to self-associate resides in its NB-ARC domain (Hu et al., 1998). Binding of the C-terminal repeat (the WD-40 repeat) domain to this region prevents spontaneous self-association, thereby negatively regulating the function of Apaf-1 (Hu et al., 1998, 1999). In the presence of cytochrome c, binding of ATP or dATP results in a conformational change promoting homooligomerization and subsequent apoptosome formation. It is tempting to speculate that the C-terminal repeat (LRR) domain of R proteins also can bind the NB-ARC domain, keeping the protein in an inactive state. Upon activation by binding of ATP and possibly other factors, R proteins may recruit additional proteins and/or self-associate to form a signalosome, similar to the apoptosome in the case of Apaf-1. In this context, it is interesting that for Rx, an NBS-LRR protein of potato conferring resistance to Potato virus X, it was shown recently that coexpression of the NBS containing the N-terminal part of the protein and the LRR domain results in an elicitor-dependent hypersensitive response in a transient expression assay (Moffett et al., 2002). In addition, the two parts of Rx interact physically in coimmunoprecipitation experiments (Moffett et al., 2002). Because coexpression of the Potato virus X elicitor resulted in the disruption of this interaction, this event might be the initial stimulus that activates Rx. Similar to Apaf-1, the NB-ARC–LRR interaction of Rx does not depend on the integrity of the P-loop motif. However, in addition to all of these similarities, there are important differences between Apaf-1 and Rx. A truncation mutant of Apaf-1 lacking the WD-40 repeat domain is constitutively active, whereas a mutant of Rx lacking the LRR domain is not. Results presented by Jiang and Wang (2000) with Apaf-1 imply a model in which the cytochrome c–mediated increase of the nucleotide binding affinity is caused by the disruption of the NB-ARC–WD-40 repeat interaction. In analogy with this model, the Potato virus X elicitor could change the nucleotide binding capacity of Rx by disrupting the NB-ARC–LRR interaction, leading to the activation of the R protein. If the mechanism of repression by the C-terminal repeats is the same in both Apaf-1 and R proteins, it would be interesting to investigate whether full-length I-2 has a lower affinity for ATP than I-2N and whether affinity could be stimulated by other factors, such as cytochrome c in the case of Apaf-1.

After cloning of a large number of R genes in the last decade, the challenge now lies in elucidating their functions in defense signaling. Our demonstration that the NBS domains of these proteins can bind and hydrolyze ATP is an important step in this direction. The combination of a biochemical approach, as described in this study, with genetic approaches will allow further dissection of the role of these proteins in signal transduction and will provide new insights into the mechanisms involved in plant disease resistance.

METHODS

Escherichia coli Expression Constructs

An NcoI-XhoI genomic fragment containing the coding region of I-2 and 1.1-kb downstream sequences (Mes et al., 2000) was ligated into pGEX-KG (Guan and Dixon, 1991) digested with NcoI and XhoI. The resulting plasmid codes for full-length I-2 fused N terminally to glutathione S-transferase (GST) (I-2F). An NcoI-NdeI (blunt) genomic fragment containing part of the coding region of I-2 (Mes et al., 2000) was ligated into pACT2 vector (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA) digested with NcoI-SmaI. The I-2 fragment then was transferred to pGEX-KG as an NcoI-XhoI fragment. This plasmid encodes amino acids 1 to 519 of I-2 fused N terminally to GST (I-2N). A plasmid encoding I-2NK207R was created by substituting the Lys-207 codon (AAG) in the P-loop motif with an Arg codon (AGG). This was performed by site-specific mutagenesis using overlap extension (Higuchi et al., 1988) with I-2N as a template. To this end, two vector primers flanking the I-2 sequence and the following mismatch primers were used: 5′-GGCGGCCAGGGCAGGACAACACTTGCTAAAG-3′ and 5′-AAGTGTTGTCCTGCCCTGGC-3′. The final PCR fragment was digested with NcoI and XhoI and ligated into pGEX-KG. The entire I-2 sequence and the mutation were verified by DNA sequencing. Plasmid pKG6210 containing the Mi-1 gene was obtained from Keygene (Wageningen, The Netherlands). A NcoI-BsmI fragment of the Mi-1 coding sequence (Vos et al., 1998) was isolated from this plasmid and ligated into the pAS2-1 vector (Clontech Laboratories) digested with NcoI and SmaI. The Mi-1 part was transferred as a MscI-SalI fragment into pGEX-KG digested with SmaI and SalI. The resulting plasmid encodes amino acids 161 to 900 of Mi-1 fused N terminally to GST and is referred to as Mi-(161-900).

Isolation of GST Fusion Proteins from E. coli

Expression vectors were transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3). Precultures were grown overnight at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium. Samples (10 mL) of these precultures were used to inoculate 100 mL of fresh Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C. After growing the culture to a density of OD600 = 0.8 to 1.0, expression was induced with 1 mM isopropylthio-β-galactoside for 4 h at 37°C. A sample was taken, and the pelleted cells were boiled in Laemmli buffer for SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250 staining or immunostaining with anti-GST monoclonal antibodies (Clontech Laboratories) or anti-I-2 antiserum (synthetic peptide). The cells of the culture were harvested and resuspended in buffer A (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, and 5 mM EDTA) and treated for 40 min with 1 mg/mL lysozyme on ice. Cells were collected and resuspended in buffer B (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100) and frozen subsequently at −20°C. The cell suspensions were thawed at room temperature and sonicated using a sonicator (MSE, Sanyo Gallenkamp, Loughborough, Leicestershire, UK) with a 3-mm-diameter probe. The insoluble part of the lysates containing the inclusion bodies was collected and washed in two sequential steps with buffer C (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100) and buffer A, respectively. Finally, the inclusion bodies were solubilized in buffer D (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 9.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 8 M urea).

Renaturation of GST Fusion Proteins

Renaturation of the solubilized inclusion bodies was based on the method described by Nguyen et al. (1996) with some modifications. The solubilized inclusion body fractions in buffer D were dialyzed stepwise against renaturation buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 9.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1.5 mM DTT) containing 20% glycerol and 6, 4, 2, or 0 M urea at 4°C. This step was followed by dialysis against renaturation buffer containing 10% glycerol and, finally, against storage buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1.5 mM DTT, and 10% glycerol). Renatured fractions were centrifuged for 45 min at 41,000g. Supernatants were divided into aliquots and stored at −80°C until use. The protein concentration of each sample was determined by the method of Bradford (1976) using BSA as a standard. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining or immunostaining with anti-GST monoclonal antibodies or anti-I-2 antiserum (synthetic peptide).

ATP Binding Assays

The binding of α-32P-ATP to purified I-2N and I-2NK207R was measured in a filter binding assay based on the method described by Rombel et al. (1999). The proteins were incubated with α-32P-ATP at concentrations ranging from 1 to 2.5 μM. The standard reaction mixture contained 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1.5 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.06 to 0.2 μM α-32P-ATP (3 × 103 to 8 × 105 cpm/pmol), and 1.5 μM protein. The mixture was incubated on ice for 15 to 20 min and then vacuum filtrated through polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon P; 0.45-μm pore size; 2.5-cm diameter filters were prepared as specified by the manufacturer [Millipore, Bedford, MA]) using a vacuum filtration manifold (Millipore). Filters were washed immediately with ice-cold buffer containing the same components as the corresponding reaction mixture except for the nucleotides. Filters were dried, and radioactivity was counted by either liquid scintillation counting or phosphorimaging (Storm; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Background corrections were performed with the values from reaction mixtures to which no protein was added. Because MnCl2 can be tested only in buffers without DTT, this component was omitted from the reaction mixture in the assays in which the divalent cation concentration was varied. For this reason also, the storage buffer of the protein was substituted with the same buffer without DTT and EDTA using Sephadex G-25 columns (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Protein concentration was measured afterward using the method of Bradford (1976). The pH was varied by adding Tris-Mes of various pH values to the reactions, resulting in a final concentration of 50 mM Tris-Mes ranging from pH 5.0 to 8.5. Binding assays with cold competitor nucleotides were performed in the presence of 8 mM MgCl2. α-32P-ATP was mixed with the cold nucleotides before adding them to the reactions. The affinity of I-2N for ATP was measured by incubation with increasing amounts of α-32P-ATP (0 to 128 μM; 3 × 103 to 2 × 105 cpm/pmol). The Kd was calculated using a Scatchard plot.

ATPase Assay

Reaction mixtures containing 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1.5 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 5 μM α-32P-ATP (4 × 104 cpm/pmol), and different concentrations of the proteins to be tested (1.5 to 1.9 μM) were incubated at room temperature. Aliquots (2 μL) were taken at the indicated times and frozen immediately at −20°C. Samples were applied to Silica Gel 60 thin layer chromatography plates (0.25 × 200 × 200 mm; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and developed in isobutyl alcohol:isoamyl alcohol: 2-ethoxyethanol:ammonia:water (9:6:18:9:15) (Yegutkin and Burnstock, 1998). Radioactive nucleotides were visualized by autoradiography using x-ray film (Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan). Unlabeled standards were located by UV absorption on thin layer chromatography plates with Silica Gel F254 (0.25 × 50 × 200 mm; Merck).

Upon request, all novel materials described in this article will be made available in a timely manner for noncommercial research purposes. No restrictions or conditions will be placed on the use of any materials described in this article that would limit their use for noncommercial research purposes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jan Berden for his support in the ATP binding experiments, Teun Munnik for his help in setting up the ATPase assay, and Martijn Rep for critical reading of the manuscript. Keygene NV is acknowledged for the generous gift of constructs encoding the R proteins I-2 and Mi.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.005793.

References

- Aravind, L., Dixit, V.M., and Koonin, E.V. (1999). The domains of death: Evolution of the apoptosis machinery. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24, 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, H.R., Sanders, D.A., and McCormick, F. (1990). The GTPase superfamily: A conserved switch for diverse cell functions. Nature 348, 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnaiyan, A.M., Chaudhary, D., O'Rourke, K., Koonin, E.V., and Dixit, V.M. (1997). Role of CED-4 in the activation of CED-3. Nature 388 (letter), 728–729. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dangl, J.L., and Jones, J.D.G. (2001). Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature 411, 826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinesh-Kumar, S.P., Tham, W.H., and Baker, B.J. (2000). Structure-function analysis of the tobacco mosaic virus resistance gene N. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 14789–14794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluhr, R. (2001). Sentinels of disease: Plant resistance genes. Plant Physiol. 127, 1367–1374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan, K.L., and Dixon, J.E. (1991). Eukaryotic proteins expressed in Escherichia coli: An improved thrombin cleavage and purification procedure of fusion proteins with glutathione S-transferase. Anal. Biochem. 192, 262–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, R., Krummel, B., and Saiki, R.K. (1988). A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: Study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 16, 7351–7367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hishida, T., Iwasaki, H., Yagi, T., and Shinagawa, H. (1999). Role of Walker motif A of RuvB protein in promoting branch migration of Holliday junctions: Walker motif A mutations affect ATP binding, ATP hydrolyzing, and DNA binding activities of RuvB. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 25335–25342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y., Benedict, M.A., Ding, L., and Nunez, G. (1999). Role of cytochrome c and dATP/ATP hydrolysis in Apaf-1-mediated caspase-9 activation and apoptosis. EMBO J. 18, 3586–3595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y., Ding, L., Spencer David, M., and Nunez, G. (1998). WD-40 repeat region regulates Apaf-1 self-association and procaspase-9 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 33489–33494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X., and Wang, X. (2000). Cytochrome c promotes caspase-9 activation by inducing nucleotide binding to Apaf-1. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31199–31203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.A., and Jones, J.D.G. (1997). The role of leucine rich repeat proteins in plant defences. Adv. Bot. Adv. Plant Pathol. 24, 90–167. [Google Scholar]

- Koronakis, V., Hughes, C., and Koronakis, E. (1993). ATPase activity and ATP/ADP-induced conformational change in the soluble domain of the bacterial protein translocator HlyB. Mol. Microbiol. 8, 1163–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macara, I.G., Lounsbury, K.M., Richards, S.A., McKiernan, C., and Bar-Sagi, D. (1996). The Ras superfamily of GTPases. FASEB J. 10, 625–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mes, J.J., van Doorn, A.A., Wijbrandi, J., Simons, G., Cornelissen, B.J.C., and Haring, M.A. (2000). Expression of the Fusarium resistance gene I-2 colocalizes with the site of fungal containment. Plant J. 23, 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, B.C., Dickerman, A.W., Michelmore, R.W., Sivaramakrishnan, S., Sobral, B.W., and Young, N.D. (1999). Plant disease resistance genes encode members of an ancient and diverse protein family within the nucleotide-binding superfamily. Plant J. 20, 317–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan, S.B., Bodeau, J., Yaghoobi, J., Kaloshian, I., Zabel, P., and Williamson, V.M. (1998). The root knot nematode resistance gene Mi from tomato is a member of the leucine zipper, nucleotide binding, leucine-rich repeat family of plant genes. Plant Cell 10, 1307–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima, T., Takaki, T., Kubota, T., Tsuchiya, T., Miki, T., Katayama, T., and Sekimizu, K. (1998). Site-directed mutational analysis for the ATP binding of DnaA protein: Functions of two conserved amino acids (Lys-178 and Asp-235) located in the ATP-binding domain of DnaA protein in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 20847–20851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffett, P., Farnham, G., Peart, J., and Baulcombe, D.C. (2002). Interaction between domains of a plant NBS-LRR protein in disease resistance-related cell death. EMBO J. 21, 4511–4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N.Y., Sackett, D., Hirata, R.D., Levy, D.E., Enterline, J.C., Bekisz, J.B., and Hirata, M.H. (1996). Isolation of a biologically active soluble human interferon-alpha receptor-GST fusion protein expressed in Escherichia coli. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 16, 835–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Q., Wendel, J., and Fluhr, R. (2000). Divergent evolution of plant NBS-LRR resistance gene homologues in dicot and cereal genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 50, 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, S., Bolland, S., Cabezon, E., Goni, F.M., and de la Cruz, F. (1997). TrwD, a protein encoded by the IncW plasmid R388, displays an ATP hydrolase activity essential for bacterial conjugation. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 25583–25590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rombel, I., Peters-Wendisch, P., Mesecar, A., Thorgeirsson, T., Shin, Y.K., and Kustu, S. (1999). MgATP binding and hydrolysis determinants of NtrC, a bacterial enhancer-binding protein. J. Bacteriol. 181, 4628–4638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, M., Goggin, F.L., Milligan, S.B., Kaloshian, I., Ullman, D.E., and Williamson, V.M. (1998). The nematode resistance gene Mi of tomato confers resistance against the potato aphid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 9750–9754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, A., Srinivasula, S.M., Acharya, S., Fishel, R., and Alnemri, E.S. (1999). Cytochrome c and dATP-mediated oligomerization of Apaf-1 is a prerequisite for procaspase-9 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 17941–17945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraste, M., Sibbald, P.R., and Wittinghofer, A. (1990). The P-loop: A common motif in ATP- and GTP-binding proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 15, 430–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffert, B.M., Vier, J., and Hacker, G. (2002). Subcellular localization, oligomerization, and ATP-binding of Caenorhabditis elegans CED-4. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290, 359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons, G., et al. (1998). Dissection of the Fusarium I2 gene cluster in tomato reveals six homologs and one active gene copy. Plant Cell 10, 1055–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y., Yuan, F., Leister, R.T., Ausubel, F.M., and Katagiri, F. (2000). Mutational analysis of the Arabidopsis nucleotide binding site–leucine-rich repeat resistance gene RPS2. Plant Cell 12, 2541–2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornero, P., Chao, R.A., Luthin, W.N., Goff, S.A., and Dangl, J.L. (2002). Large-scale structure-function analysis of the Arabidopsis RPM1 disease resistance protein. Plant Cell 14, 435–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traut, T.W. (1994). The functions and consensus motifs of nine types of peptide segments that form different types of nucleotide-binding sites. Eur. J. Biochem. 222, 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Biezen, E.A., and Jones, J.D.G. (1998). The NB-ARC domain: A novel signalling motif shared by plant resistance gene products and regulators of cell death in animals. Curr. Biol. 8, 226–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos, P., et al. (1998). The tomato Mi-1 gene confers resistance to both root-knot nematodes and potato aphids. Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 1365–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, J.E., Saraste, M., Runswick, M.J., and Gay, N.J. (1982). Distantly related sequences in the alpha- and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1, 945–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X., Chang, H.Y., and Baltimore, D. (1998). Essential role of CED-4 oligomerization in CED-3 activation and apoptosis. Science 281, 1355–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yegutkin, G.G., and Burnstock, G. (1998). Steady-state binding of [3H]ATP to rat liver plasma membranes and competition by various purinergic agonists and antagonists. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1373, 227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H., Henzel, W.J., Liu, X., Lutschg, A., and Wang, X. (1997). Apaf-1, a human protein homologous to C. elegans CED-4, participates in cytochrome c-dependent activation of caspase-3. Cell 90, 405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]