Infective endarteritis (IE) was a fatal complication and the most common cause of death (45%) in patients with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), before the introduction of antibiotic therapy and surgical closure of the ductus. The annual risk of IE in patients with PDA was estimated to be 0–45% [5]. Wide use of antibiotics and surgical closure of PDA has reduced significantly the incidence of IE in patients with PDA, as well as the mortality rate associated with it. Despite these changes, however, the prevention of IE remains the main indication for PDA closure.

Two-dimensional echocardiography (transthoracic & transesophageal) is the most sensitive and widely used method in identifying vegetations associated with IE, as well as in detecting the underlying heart disease, even in cases of clinically silent PDA (no symptoms, no murmur).

Case report

A forty-three year old Caucasian woman, with no history of heart disease, was admitted to the hospital due to prolonged fever, palpitations, fatigue and loss of body weight (10 kg) during the past 2 months. Two months before, she had undergone a complicated tooth extraction, which was not completed. The patient did not follow the antibiotic treatment prescribed by the Dentist after the procedure. Twenty-four hours later she developed high fever with chills. During the following two months, her temperature showed fluctuations and was partially controlled with simple analgesic and antipyretic drugs. She did not complain for any other symptoms. It was the marked weakening and palpitations, which led her to seek for medical help.

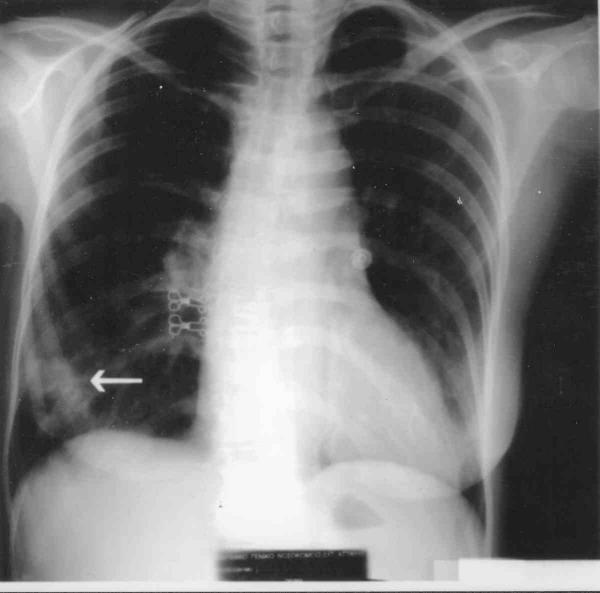

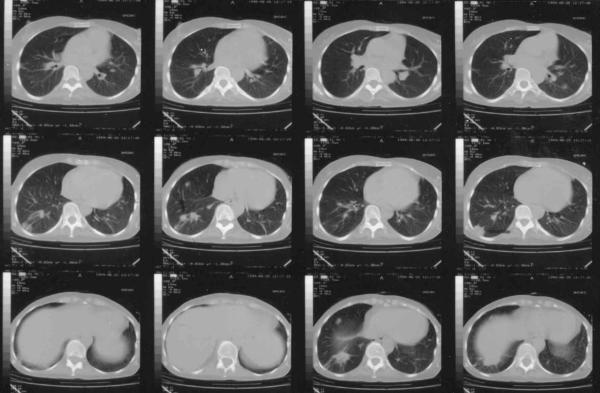

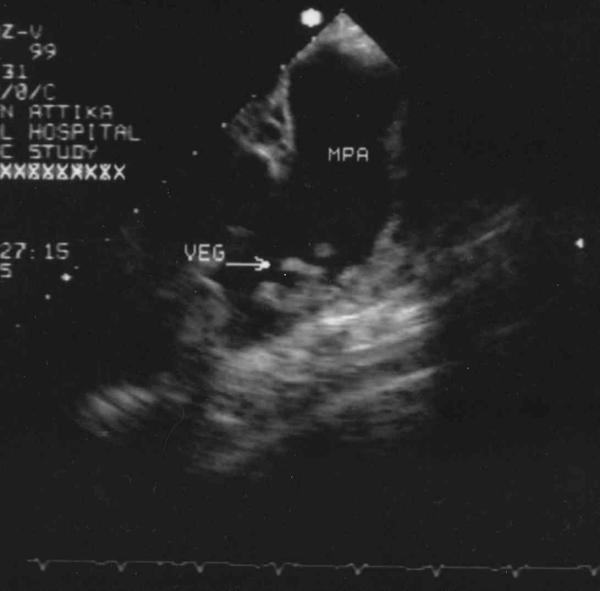

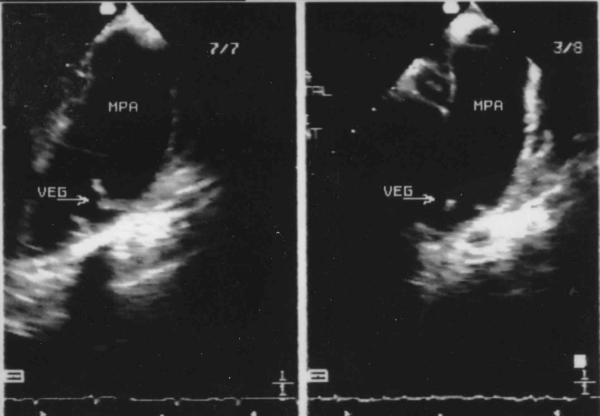

No further substantial information was obtained from the personal medical and family history of the patient. A few years ago an echo was suggested to her due to a loud systolic murmur, but she did not follow this advice. On physical examination, she appeared to be lean, suffering, with poor dental hygiene. Her BP was 100/75 mmHg, HR was 110 bpm and respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min. There was a palpable thrill and a 4–5/6 continuous murmur with late systolic accentuation at the upper left sternal border. Pulmonary fields were clear on auscultation. The spleen was palpable 4 cm under the left subcostal border. Laboratory investigations revealed hypochromic anemia with microcytosis (Hb 9.66 g/dl), normal white cell count and ESR of 100 mm at the 1st hour. Renal and liver function were normal. A chest x-ray film demonstrated a consolidation at the base of the right lung and chest CT revealed pulmonary infiltrations in both lungs, suggesting septic emboli (Figure 1,2). Blood cultures were positive for Streptococcus Sanguis II. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) demonstrated normal cardiac dimensions and function, normal valves with no vegetations and dilatation of the right ventricular outflow tract under the pulmonary valve. The main pulmonary artery and descending aorta were also dilated. Color Doppler revealed a high velocity retrograde turbulent flow (4 m/sec) emerging from the descending aorta towards the pulmonary artery at the level of its bifurcation, findings consistent with PDA. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) confirmed the presence of PDA and revealed multiple mobile vegetations on the pulmonary artery wall and at the pulmonary end of the PDA (Figure 3, Video – see Additional file 1). The patient then received 24·106 IU of penicillin G and 240 mg of gentamycin IV daily. Ten days later, her temperature normalized and after 4 weeks she underwent a new TEE, in which the vegetations were smaller but still present (no change in number of vegetations, but they appear to be brighter and 2–3 mm shorter) (Figure 4). After receiving a full six-week antibiotic regimen, she subsequently underwent surgical closure of the PDA. Intraoperative findings: Dilated and atherosclerotic ductus arteriosus with small calcified vegetations across its lumen and at its pulmonary end. Ligation and closure of the ductus were performed without complications. Six months after the surgery the patient remains in a good clinical condition.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray showing a consolidation at the base of the right lung (arrow).

Figure 2.

Chest CT demonstrating multiple infiltrations representing septic emboli (arrows).

Figure 3.

Transesophageal Echo demonstrating vegetations at the pulmonary artery wall near the ductus end. MPA: Main pulmonary artery. VEG: Vegetations.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the size of the vegetations 25 days after antibiotic treatment, as they are seen by transesophageal Echo.

Discussion

The presence of PDA is important during fetal life, when most of the output of the right ventricle bypasses the unexpanded lungs by way of the ductus arteriosus [1]. Its closure takes place after birth, functionally, probably as a result of the increased PO2 and anatomically during the first 6 weeks of life with the development of fibro-connective tissue. In about 1% of all infants the ductus remains patent after the first year of life [5], probably due to a disturbance of the ductus wall elastic tissue [1]. After this age, spontaneous closure is extremely rare [5].

The most common complications of this congenital disease are left heart failure and ductus IE, while pulmonary artery IE[6] and aorta or/and PA thrombosis [7] have been reported. PDA is a common cause of CHF in newborns. Development of pulmonary hypertension represents a protective mechanism for LV, as the left to right shunt gets restricted or reversed (Eisenmenger)[8,9]. The non-restrictive type of PDA is characterized by development of CHF during the first year of life, whether restrictive PDAs usually remain asymptomatic and are accompanied with an increased risk of IE especially after the second decade of life.

IE was the most common cause of death (42 – 45%)[5] in these patients before the antibiotic era. Antibiotic use and the development of surgical closure of the ductus have drastically reduced the incidence of IE [10], so that it is now considered as rare [4]. Nevertheless some investigators suggest that routine closure of PDA for the sole purpose of eliminating the risk of IE is unnecessary [10]. In all newborns (even in the prematures), TTE is the method of choice for establishing the diagnosis of PDA. In older patients a PDA is not easily visualized with TTE. TEE, especially multiplane TEE, appears to be more sensitive and of superior diagnostic value in detecting the ductus, assessing the pulmonary/systemic flow and vascular resistance ratios [18] and also the vegetations in case of IE (usually located into the ductus near its pulmonary end). Moreover, TEE can better evaluate the result of surgical or percutaneous closure [11,12].

Patients with a PDA are at an intermediate to high risk of IE and should be prescribed antibiotic prophylactic treatment according to the AHA guidelines for high-risk patients.

PDA treatment can be conservative or invasive (surgical or percutaneous). Indomethacin (0.2 mg/kg IV administered during the first 2 – 7 days of life) is the appropriate drug therapy [1]. In 10% of patients who do not respond to Indomethacin, invasive closure of the ductus needs to be considered. PDA with echo evidence of volume overloaded or failing LV has to be operated in order to avoid clinical CHF [10]. In addition, IE seems to occur more often in high shunt-flow ductuses (i.e. larger in diameter), although cases of IE in clinically silent PDAs have been reported [13,17]. A low shunt-flow PDA which doesn't seem to affect LV both clinically and in serial echo evaluation, poses the question whether it should be closed in order to diminish the possibility of IE, which increases further with age [5]. In our experience, the most appropriate strategy is to refer all PDAs but the clinically silent ones for invasive closure, inasmuch as the best method to follow-up the non-operated patients has not been established yet. Surgical techniques for PDA closure include ligation and division, simple ligation, hemaclip application [14] and minimally invasive techniques, such as video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery [19]. Development of percutaneous closure of PDA (Rashkind double umbrella, single or multiple coils, implanted Amplatzer duct occluder) shows good results with minimum complications and is considered to be a safe and feasible alternative for adult patients who are either not fit for open chest surgery or who prefer a less invasive approach [15,16,21]. Single coil transcatheter occlusion is recommended for small ducts (< 2 mm), while multiple coil approach or Amplatzer duct occluder is preferred for a larger ductus [16,20]. Occlusion rates achieved with this regimen are above 95% [16]. In elderly patients, surgical treatment might be advocated due to technical difficulties for percutaneous closure (calcified aortic arch) or concomitant lesions to be treated such as aortic stenosis or severe coronary artery disease [22].

Supplementary Material

Transesophageal Echo demonstrating vegetations at the pulmonary artery wall near the ductus end. VEG: Vegetations. Transesophageal view at the base of the heart showing multiple mobile vegetations at the pulmonary artery wall near the ductus end.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the patients' details.

Contributor Information

Nikos T Kouris, Email: nikoskou@otenet.gr.

Maria D Sifaki, Email: ngndat@otenet.gr.

Dimitra D Kontogianni, Email: ngndat@otenet.gr.

Ioannis Zaharos, Email: MED4U@winweb.gr.

Eleni M Kalkandi, Email: ngndat@otenet.gr.

Haris E Grassos, Email: harigrass@yahoo.gr.

Dimitris K Babalis, Email: ngndat@otenet.gr.

References

- Friedman WF. In Braunwald Heart diseases. 5. WB Saunders; 1997. Congenital heart disease in infancy and childhood; pp. 904–906. [Google Scholar]

- Bankl H. Congenital malformations of the heart and great vessels: synopsis andpathology, embryology and natural history. Baltimore: Urban and Schwarzenberg. 1977.

- Zarich S, Leonardi H, Pippin J, et al. Patent ductus arteriosus in the elderly. Chest. 1988;94:1103–1105. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.5.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggon IC, Qureshi SA. Is the prevention of infective endarteritis a valid reason for closure of the patent arterial duct? Eur Heart J. 1997;18:364–366. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. Natural history of persistent ductus arteriosus. Br Heart J. 1968;30:4–13. doi: 10.1136/hrt.30.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Barron J, Attie F, Buendia-Hernandez A, et al. Echocardiographic recognition of pulmonary artery endarteritis in patent ductus arteriosus. Am Heart J. 1985;109:368–370. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90611-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp S, Bedard M, Farooki ZQ, Arciniegas E. Pulmonary artery thrombus associated with the ductus arteriosus. Am Heart J. 1986;11:796–797. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(86)90122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perloff JK. In Braunwald Heart diseases. 5. WB Saunders; 1997. Congenital heart disease in adults; p. 966. [Google Scholar]

- Massie BM, Amidon TM. Heart. In: Tierney LM Jr, McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA, editor. In Current medical diagnosis and treatment. 38. Appleton & Lange; 1999. pp. 347–348. [Google Scholar]

- Thilen N, Astrom-Olsson K. Does the risk of infective endarteritis justify routine patent ductus arteriosus closure? Eur Heart J. 1997;18:503–506. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumbarello R, Sanna A, Cardu G, et al. Usefulness of transesophageal echocardiography in the pediatric catheterization laboratory. Am J Cardiol. 1993;71:1321–1325. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90548-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade A, Vargas-Barron J, Rijlaarsdam M, et al. Utility of transesophageal echocardiography in the examination of adult patients with patent ductus arteriosus. Am Heart J. 1995;130:543–546. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90364-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzer DY, Spray TL, McMullin DO, et al. Endarteritis associated with a clinically silent patent ductus arteriosus. Am Heart J. 1993;125:1192–1193. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavroudis C, Backer CL, Gevitz M. Forty-six years of patent ductus arteriosus division at Children's Memorial Hospital of Chicago. Standards for comparison. Ann Surg. 1994;220:402–409. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199409000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievert H, Ensslen R, Fach A, et al. Transcatheter closure of patent ductus arteriosus with the Rashkind occluder. Acute results and angiographic follow-up in adults. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:1014–1018. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking MCK, Benson LN, Musewe N, et al. Transcatheter occlusion of the persistently patent ductus arteriosus: forty-month follow-up and prevalence of residual shunting. Circulation. 1991;84:2313–2317. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.6.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthenakis FI, Kanakaraki MK, Vardas PE. Silent patent ductus arteriosus endarteritis. Heart. 2000;84:619. doi: 10.1136/heart.84.6.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang ST, Hung KC, Hsieh IC, et al. Evaluation of shunt flow by multiplane transesophageal echocardiography in adult patients with isolated patent ductus arteriosus. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:1367–1373. doi: 10.1067/mje.2002.125918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensky AS, Raines KH, Hines MH. Late follow up after thoracoscopic ductal ligation. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:360–361. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)00936-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeggi ET, Fasnacht M, Arbenz U, et al. Transcatheter occlusion of the patent ductus arteriosus with a single device technique: comparison between the Cook detachable coil and the Rashkind umbrella device. Int J Cardiol. 2001;79:71–76. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5273(01)00406-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Leung YL, Kwong NP, et al. Transcatheter closure of patent ductus arteriosus in Chinese adults: immediate and long term results. J Invasive Cardiol. 2003;15:26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freneken M, Krian A. Surgical occlusion of persistent ductus arteriosus in advanced age-determining indications based on 3 case reports. Z Kardiol. 1996;85:112–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transesophageal Echo demonstrating vegetations at the pulmonary artery wall near the ductus end. VEG: Vegetations. Transesophageal view at the base of the heart showing multiple mobile vegetations at the pulmonary artery wall near the ductus end.