SYNOPSIS

Immediately following the Master Settlement Agreement of 1998 and the corresponding growth of new and existing tobacco control programs, it became clear that tobacco prevention and control organizations required technical assistance to help them carry out their missions. The Tobacco Technical Assistance Consortium (TTAC) was established at the Rollins School of Public Health in 2001 to provide tailored technical assistance services to meet the needs of the expanded workforce and to build tobacco control capacity.

To understand whether and how TTAC's technical assistance enhanced capacity, TTAC conducted an evaluation of its services through semi--structured telephone interviews with the primary contacts and one to two additional informants for each of 48 technical assistance services provided over an 18-month period. The majority of respondents reported they had increased knowledge and skills in tobacco control, strengthened leadership skills, developed or strengthened partnerships with other tobacco control organizations, and changed the way they practice tobacco control following the assistance. More modest improvements were noted in the areas of increased organizational support and policy change at the local or state level.

Organizations and coalitions address similar issues in unique ways, based on their cultural, political, community, and environmental realities.1 Technical assistance allows for the customization of services to meet the individualized needs of an organization. In public health, and tobacco control specifically, technical assistance usually involves assessing an organization's need, then providing tailored assistance by an expert to help build the identified capacity. Quality technical assistance engages both the client and the technical assistance provider in a relationship based on trust, collaboration, and goodwill as the need is assessed and as the technical assistance plan of action is determined and implemented.2

The need for technical assistance in tobacco control expanded significantly as a result of the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) of 1998.3 This historic legal settlement provided 46 participating states with an infusion of funds to develop new and expand existing tobacco prevention and control programs.4 The additional funds resulted in the need for an expanded public health workforce focused on tobacco-related issues. Challenges related to workforce preparation common in public health were also evident in tobacco control during this period of rapid expansion. It has been noted, for example, that more than three-quarters of the public health workforce has little or no training or formal education in public health.5 This new tobacco control workforce needed resources to build their knowledge and skills in tobacco control. At the same time, experienced tobacco control professionals were facing a more complex environment with new sets of expectations for performance. They, too, could benefit from additional expertise to advance their skills.6

TOBACCO TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE CONSORTIUM

It was clear that the new and existing tobacco prevention and control organizations would require training and technical assistance to carry out their missions, as well as to advocate for continued MSA funding.3 In order to meet the increasing technical assistance and training needs of national, state, and local organizations working on tobacco prevention and control agendas, three national organizations devoted to tobacco control—the American Legacy Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the American Cancer Society—conceived and funded the Tobacco Technical Assistance Consortium (TTAC) in 2001. The TTAC is located at the Rollins School of Public Health (RSPH), Emory University, and operates with a small core staff of public health professionals and RSPH faculty dedicated to tobacco prevention and control efforts. TTAC also contracts with tobacco control expert consultants from around the country to provide specific services.

TTAC's mission is to build capacity in tobacco control by increasing knowledge and skills on tobacco-related issues, fostering leadership among the workforce, increasing organizational support, and strengthening partnerships between and among tobacco control organizations. One of the ways that TTAC strives to build capacity among tobacco control organizations is by providing individualized, customized technical assistance to requesting organizations at national, state, local, and community levels. TTAC's goal is to provide assistance in translating research into applied practice to enable programs to achieve their goals in tobacco prevention and control. TTAC's role also includes organizational and infrastructure assistance, as well as legal, lobbying, and advocacy training and assistance.

In the years following the MSA, selected states, TTAC, and the American Legacy Foundation conducted needs assessments to provide detailed information on the technical assistance and training needs of the tobacco prevention and control workforce.6 The results of the assessments showed that the key needs were information and information exchange among organizations and programs, mentoring and training opportunities for new staff, advanced skill training for seasoned staff, organizational infrastructure and strategic planning support, and organizational sustainability planning. To meet the varied needs identified in the assessment, TTAC established a national pool of expert consultants to respond to individualized technical assistance requests from organizations around the country. The consultants were chosen using a rigorous selection process, and are considered leaders by their peers in their specific areas of expertise in tobacco control. The number of qualified consultants identified and their varied areas of expertise allow TTAC to nimbly respond to requests from the field.

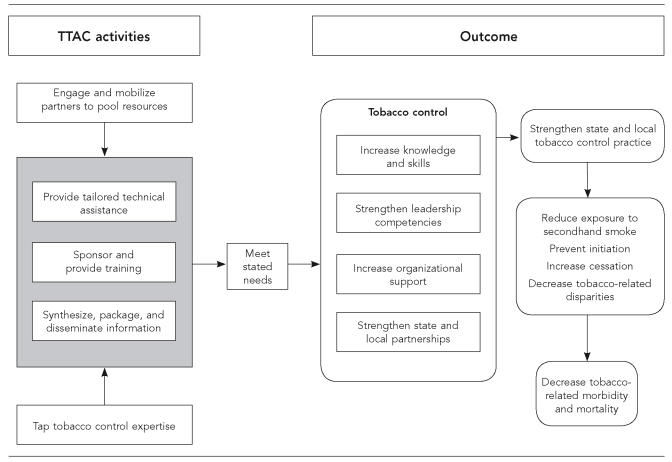

The purpose of this article is to present results from an evaluation of TTAC's technical assistance services. The evaluation was designed to assess whether TTAC strengthens tobacco control capacity among those it serves, and if so, in what ways. The evaluation was guided by a logic model that combined insights gained from TTAC's needs assessment with literature on community capacity that highlights the importance of skills, leadership, resources, and partnerships.7–9 The logic model (Figure 1) shows how TTAC's activities should meet clients’ stated needs and improve tobacco control capacity in knowledge and skills, leadership, organizational support, and partnerships. Improvements in capacity, in turn, should lead to strengthened practice, and ultimately contribute to achievement of national objectives for reducing death, disease, and disability from tobacco use.

Figure 1.

Logic model for the Tobacco Technical Assistance Consortium (TTAC)

EVALUATION METHODS

Population

Forty-eight organizations that received technical assistance from March 2003 through August 2004 were included in the evaluation. The requests came from a wide variety of organizations, including state-wide organizations (n521); organizations that cater to specific priority populations (n58); community-based organizations (n58); national organizations (n56); and professional organizations (n55). The requests came from 17 different states: Alaska, Georgia, Hawaii, Kentucky, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, South Dakota, Washington, Maryland, Tennessee, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Oklahoma, Colorado, Indiana, and Iowa. There were also four priority populations that received technical assistance from TTAC during this time period: Alaskan Native, Hispanics/Latino, African American, and Native American.

TTAC provided several types of technical assistance, including strategic planning assistance (n520); speakers and trainers to present on specific areas related to tobacco control at various workshops, conferences and trainings (n517); sustainability planning (n53); needs assessment and evaluation (n 5 4); grant writing (n 5 1); educational product development (n52); and assistance with a policy proposal (n51). The speakers and trainers for the workshops, conferences, and trainings presented information on the following topics: smoke-free air campaign strategies, tobacco basics, tobacco prevention and cessation among women, tobacco and faith-based organizations, funding and media interviewing techniques, components of a comprehensive cessation statewide program, “reduced-risk” tobacco products, the economic impact of tobacco use, advocacy training for Latinos, and the targeting of African Americans by the tobacco industry. The technical assistance was provided by expert consultants from around the country who had been approved through TTAC's selection process. The consultants who provided the services were selected from the consultant pool by the TTAC staff and approved by the requesting organization.

Procedures

The data collection took place between September 2003 and March 2005. Three months after completion of each project, the TTAC evaluation staff sent an e-mail message to the primary contact for each organization to request they take part in a telephone interview to evaluate the TTAC service they had received. Staff followed up by telephone to schedule an interview. During each interview, the primary contacts were asked to name two additional informants who had been recipients of the technical assistance and could provide their views on the TTAC service. The interview guide was shared with respondents prior to the interviews. All interviews were audio taped with permission from the respondent and averaged approximately 30 minutes in length. Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to the interviews. Overall, 94 interviews were conducted to assess 48 different TTAC services, for an average of 2.0 respondents per service.

Interview guide

The interview guide included two major sections: satisfaction with the services, and the impact of these services on tobacco control capacity and practice. The capacity-building section was semi-structured with both closed (yes/no) and open-ended questions. Specific capacity-related topics included increased knowledge and skills, strengthened leadership competencies, increased organizational support, strengthened state and local partnerships, progress on state-wide or local tobacco control policies, and changes in tobacco control practice that resulted from work with TTAC. For example, to assess impact on leadership, respondents were asked: “Did [TTAC service] help you to become a better leader in tobacco control?” If respondents answered affirmatively, they were asked, “In what ways are you a better leader now?” and “How, specifically, did [TTAC service] help you improve in these areas?”

Data analysis

All of the interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. A detailed coding scheme was developed to capture themes from the open-ended questions on capacity-building. The coding structure was organized into the following major sections: type of service, consultant, knowledge and skills, leadership, partnerships, organizational support, and practice. More detailed codes were created within each of the major topics. Each transcript was independently coded by two members of the evaluation team, with discrepancies resolved through discussion. Text retrievals on specific codes or combinations of codes were then completed with the use of QSR-N6, a qualitative data analysis software package.10 Additional in-depth content analysis was then performed on these text retrievals to identify major themes.11 Data matrices were created with major themes on the Y-axis and respondents on the X-axis.12 Cells contained brief summaries of the responses. Separate analyses were conducted for each TTAC service and each major topic covered in the interviews. These matrices facilitated analyses of the data for strength of theme. The close-ended (yes/no) questions were used to consistently classify strength of theme, using the technical assistance service as the unit of analysis, as follows: several (3–7), some (8–15), many (16–29), most (30–43), almost all (44–47), and all (48).

RESULTS

Knowledge and skills

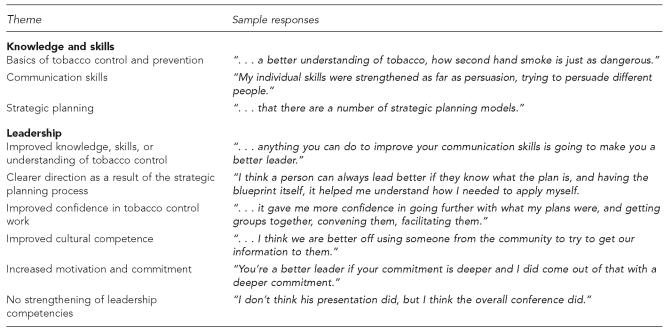

Respondents were asked to list two or three things they learned and two or three skills they gained as a result of the technical assistance provided by TTAC. All of the participants were able to identify knowledge and/or skill areas that were improved as a result of the assistance. The most prominent theme to emerge was increased knowledge on topics that can be categorized as basics of tobacco prevention and control (Figure 2). Examples include clean indoor air “sound bites,” media communication messaging, role of media, tactics for combining tobacco prevention and chronic disease prevention, tobacco control efforts, strategic planning tactics, best practices in tobacco control, cultural and community competency, and marketing tactics used by the tobacco industry.

Figure 2.

Themes related to increased knowledge, skills and leadership

Some respondents reported they had improved their communication and presentation skills as a result of the technical assistance. Strategic planning was another skill often gained as a result of the technical assistance. In addition, some respondents reported improvement in strategic planning skills specifically, while others reported an improved ability to prioritize their goals and work.

Other respondents reported they acquired organizational, sustainability planning, leadership, needs assessment, and advocacy skills, as well as improved ability to provide technical assistance. Respondents also reported that the technical assistance they received improved their confidence in their professional abilities. Coalition-building and evaluation were also mentioned.

Leadership

Respondents were asked whether the technical assistance service funded by TTAC helped them become a better leader in tobacco control, either directly or indirectly (Figure 2). Recipients of most of the services believed their leadership abilities were strengthened in some way, most commonly by improving knowledge, skills, or understanding of tobacco control issues. In addition, some respondents spoke of how the strategic planning process supported by TTAC helped them define their direction, which they felt contributed to good leadership. Several others spoke of how the TTAC-supported service gave them confidence in their abilities, thereby strengthening leadership.

Another group of respondents spoke about how the TTAC-supported technical assistance enhanced their cultural competency. One respondent, for example, described how she learned more about the Filipino community and another spoke of how it helped her understand what some of the needs are in working collaboratively with priority populations. Another theme that emerged from several respondents was increased motivation to be more active in tobacco control. In addition, several respondents talked about how they were more committed to community participation and the need for obtaining input from the full coalition. Only a few respondents reported no strengthening of leadership competencies.

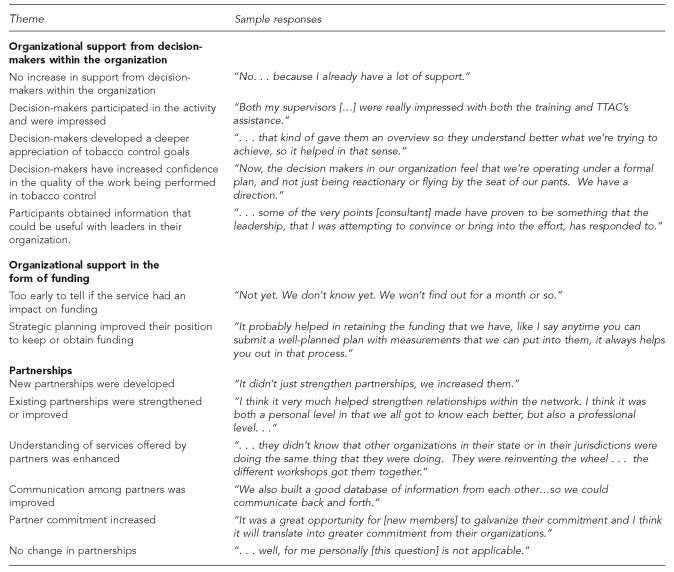

Organizational support

Two dimensions of organizational support were examined: support from major decision-makers within the respondents’ organizations and keeping and obtaining funding (Figure 3). Respondents from most of the projects had neutral or mixed feelings about the impact of the TTAC-supported service on support from decision-makers in their own organizations. They explained that they already had a lot of support within their own organization, the project did not target leaders in their organizations, or that decisions were currently made at their level and support from higher-level administrators was not relevant. Others simply responded “not yet.”

Figure 3.

Themes related to enhanced organizational support and partnerships

Respondents from some of the projects, however, commented that support from decision-makers within their own organizations had increased, either directly or indirectly, as a result of the TTAC-supported service. These respondents were asked to explain how this form of organizational support was enhanced. Mechanisms included leader participation in the TTAC-supported activity, decision-makers’ enhanced understanding of what tobacco control advocates were trying to achieve, instilling a feeling of confidence among decision-makers in the quality of the plans and work being performed in tobacco control, and provision of information that could be used by leaders in their own organizations.

Respondents were also asked whether and how the TTAC service helped keep or obtain new funding for tobacco control. Respondents associated with many of the TTAC services reported it had not contributed to keeping or obtaining funding, although the training and/or technical assistance services still had the potential to contribute, according to those interviewed. The most common response to this question was “not yet” or “it remains to be seen.”

Another common response made by recipients of some of the services was that they were now in a better position to keep or obtain funding, most often as a result of strategic planning and/or strengthened partnerships. Several respondents commented that the technical assistance was useful to them in terms of determining how to best spend their existing money.

Partnerships

Almost all of those interviewed reported that the TTAC service strengthened their tobacco-related partnerships (Figure 3). The most dominant theme was that the TTAC service resulted in the development of new partnerships with other tobacco control professionals and/or organizations. Another strong theme was that the TTAC service helped strengthen or improve existing partnerships. Other themes that emerged included a greater understanding of services offered by partners, improved communication among partners, and increased partner commitment. Several respondents indicated the question related to strengthening partnerships was not applicable to the type of service they received from TTAC. These services included a presentation to a state team on tobacco control policy, the implementation and analysis of a needs assessment project, and a presentation on program evaluation, among others.

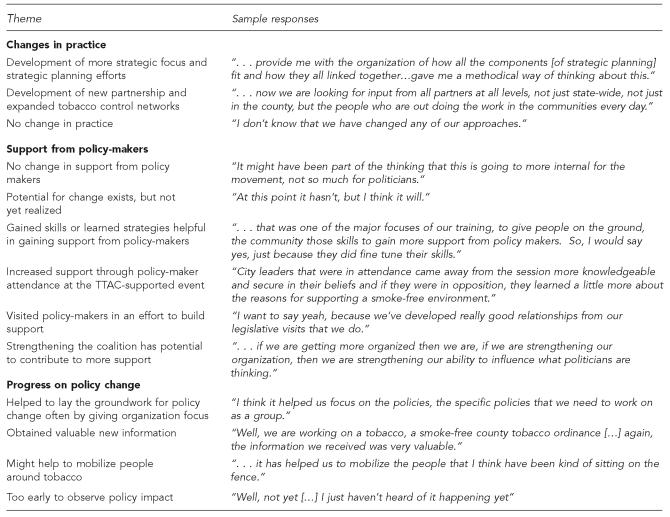

Tobacco control practice

Respondents were asked whether the TTAC technical assistance service changed the way they practiced tobacco control in their state or community (Figure 4). Many commented that the service they received from TTAC improved or changed their tobacco control efforts, most notably through strategic planning efforts and development of a more strategic focus or through development of new partnerships and expanded tobacco control networks. One respondent, for example, spoke of how the technical assistance had helped her organization “get more focused and take more ownership,” while another commented that the assistance helped broaden her organization's focus on how to mobilize the Latin American population. Others talked of technical assistance services helping them develop a method of strategic planning, and how services helped them focus on what worked and what did not work. Another respondent discussed how his organization had strategically restructured and was now using a “bottom up, more inclusive” approach to tobacco control so that more individuals and agencies have opportunities for leadership.

Figure 4.

Themes related to changes in practice and policies

In addition, respondents commented on the development and strengthening of partnerships and networks as a result of the technical assistance services they received from TTAC. According to those interviewed, communities and organizations are now working together and sharing experiences more so than before the TTAC service. Some organizations spoke of the relationships that have been built and the collaborative efforts that have resulted; others discussed the increase in communication among groups and of inclusivity that resulted in bringing new partners to the table and allowing for leadership from the new groups.

Other practice-related changes were increased awareness of tobacco control efforts; being more prepared to respond to community needs; the addition of new programs, coalitions, or services; a clearer idea and understanding of fundraising and fundraising practices; and increased commitment and enthusiasm for tobacco control work. A greater knowledge of policy-making and advocacy and increased confidence in working with legislatures were also reported as changes resulting from TTAC services.

Respondents from some of the organizations that were provided technical assistance services by TTAC reported that the question on changing practice as a result of the service provided was not applicable to the service they received or that the service did not result in a change in practice. Services seen as not applicable included a satellite broadcast for training on chronic disease topics and a presentation on tobacco control policy to state teams. Examples of services that did not result in a practice change, according to those interviewed, included a presentation to a group of attorneys general on tobacco “risk reduction” products and a presentation to environmental health practitioners on ventilation issues.

Policy change

Because tobacco control practice focuses heavily on environmental and policy change, the evaluation also assessed how the TTAC service may have influenced policy work. One question explored whether the TTAC service helped obtain support from policy makers. Most respondents across services had mixed views on whether support from politicians had increased or reported that such support had not increased. Others mentioned the project was not intended to achieve this type of change, that their organization does not deal with politicians, or that substantive political support existed already. Some of these respondents commented that the potential for policy change existed, but had not yet been realized.

For some of the services, however, respondents consistently described an indirect impact on support from policy makers. In these cases, respondents typically described skills or strategies they had strengthened for gaining support, such as messages to use in speaking to local politicians or more sophisticated approaches to building political support (Figure 4).

Respondents associated with several of the TTAC-supported services described how policy makers and/or lobbyists had attended the event, which may have increased their level of support. In addition, several respondents spoke of visiting policy-makers as a step in strengthening their support. Others spoke of how strengthening their coalition had the potential to contribute to more support from politicians.

Respondents were also asked whether the TTAC-supported service helped them make any progress on state or local policies. Many felt that the TTAC service contributed in some way to their tobacco control policy goals or at least moved them in the right direction. The strongest theme by far was that the TTAC service helped lay the groundwork for policy action and helped to give their organization focus (Figure 4). Others discussed how new information about tobacco control strategies was valuable in contributing to policy action.

Consultation on strategic planning was mentioned by recipients of several TTAC-supported services as related to progress in the policy area. Inclusion of policy-related objectives in strategic plans was seen as especially relevant. Other themes were that the TTAC service might help mobilize people around tobacco issues, that restructuring of the coalition enhanced the potential for effective policy action, and that new connections and improved relationships with key partners were useful steps in the policy process.

Some of those interviewed were less able to see how the service they received might have contributed to progress on the policy front. They tended to comment that it was too early to know if the technical assistance contributed to policy or that there was no expectation that the TTAC service would contribute to state or local tobacco control policy.

DISCUSSION

A major purpose of technical assistance in tobacco control is to strengthen the capacity of the workforce to design and implement the most effective programs possible. Successful tobacco control practice requires a complex set of skills and resources. Consequently, technical assistance needs vary widely depending on the maturity of the program, funding level, staff experience and training, partner organizations, demographics, culture, and numerous additional contextual factors. Given the individualized nature of technical assistance, designing an evaluation to rigorously assess changes in capacity and associated outcomes across multiple projects is challenging. This article presents one approach to assessing the extent to which, and perhaps more importantly, how, technical assistance made a difference to those receiving such service. Because of the diversity of services provided (e.g., speakers at conferences, assistance with strategic planning, etc.), it was important to identify outcomes that were theoretically relevant to the major types of services delivered. Thus, the evaluation focused on general dimensions of capacity: knowledge and skills, leadership, organizational support, and partnerships. Designing specialized evaluations for each unique project would have been cost- and time-prohibitive and would have made it difficult to draw general conclusions about TTAC's technical assistance services.

Results from this evaluation suggest that the TTAC services were most effective in building knowledge and skills on the basics of tobacco control and developing and/or strengthening partnerships. Many also reported strengthened leadership skills and changes in their practice of tobacco control as outcomes of the technical assistance. The positive finding related to increased knowledge and skills may have resulted from the fact that TTAC services were customized to meet the specific needs of the requesting organizations, provided at the level of expertise or instruction each required, and at the organizations’ times of need. Also, the requests were for trainings or technical assistance services that provided either information related to tobacco control issues or skill-building opportunities.

As found in this evaluation, participants believed their leadership skills were enhanced as knowledge was increased, skills were enhanced, and confidence was gained. The findings also showed that partnerships were built or strengthened as key stakeholders from organizations, states, or coalitions engaged in strategic planning efforts or came together at workshops and training provided through TTAC. Participant comments suggested that the new and expanded partnerships, along with improvements in knowledge and skills, contributed to changes in their tobacco control practice.

Areas with more modest improvements included increased support from organizational decision-makers, keeping and obtaining funding, and policy change. There are multiple possible explanations for these findings. First and foremost is the question of whether these outcomes are relevant to all of the different types of services delivered by TTAC. Almost a third of the services involved speakers or trainers at workshops, conferences, and training events. It is quite likely that these activities were not of sufficient intensity or duration to trigger complex and longer-term changes. Second, in many cases, the respondents felt it was too early to assess an impact. The follow-up interviews were done just three months after delivery of the technical assistance service. Insufficient time came up most often with respect to funding and legislative cycles. Third, mainly in the case of organizational support, many respondents noted there was not room for significant improvement given the high levels of support they already received from upper administration in their organizations.

Limitations

This evaluation has several limitations. First, the responses are based on self-report and are not validated with objective measures of changes in capacity. It should be noted that objective measures and standard methodology for assessing changes in capacity are not yet developed. Second, respondents were interviewed by the funding organization and may have given socially desirable responses as a result. Interviewing more than one respondent per service helped to strengthen the validity and reliability of the findings, as did informing respondents that “not applicable” was an acceptable response. Third, there was no baseline assessment and no comparison group, making it difficult to attribute the noted changes exclusively to the TTAC service. Therefore, results should be viewed as respondents’ perceptions of how the services helped to build capacity. Last, respondents who were not the primary contact for the technical assistance provided by TTAC may have had varying levels of awareness of the technical assistance and its impact on capacity.

As mentioned earlier, an additional challenge stemmed from the wide variation in services delivered across the various organizations, making it difficult to determine and assess similar outcomes across such a broad range of activities. For this reason, some of the concepts measured, such as additional funding or policy change, may not be relevant to each of the TTAC services provided (e.g., funding a speaker on a given topic).

Implications

This evaluation has several implications for the provision and evaluation of technical assistance in tobacco control. One such implication is that rigorous evaluation of individualized technical assistance is challenging to do across multiple types of services with limited resources. Because of TTAC's flexibility in providing a range of services, each service was tailored to the requesting organization's needs. Ideally, the evaluation would have assessed specific outcomes related to each service by obtaining baseline measures, using all potential participants for the sampling frame, obtaining longer-term follow-up data, and collecting data from a comparison group. Practically speaking, this would have resulted in over 40 unique evaluation projects, each with its own set of outcomes. A reasonable alternative is to focus on particular types of service, where there is greater uniformity in expected outcomes and in intensity of the experience. Future evaluations could also focus on the cost-effectiveness of different models of technical assistance delivery and cost/benefit analysis of individualized, customized assistance services.

This evaluation was designed to provide TTAC with a “big picture” view of whether and how TTAC strengthened capacity in the tobacco control workforce through tailored technical assistance. TTAC chose breadth over depth given its information needs and the resources available for evaluation. The evaluation not only provided TTAC with valuable information on the quality of the services and the capacity-building benefits of providing individualized, customized technical assistance, but it also allowed TTAC to prioritize and develop its own strategic plan. The types and frequency of specific requests, coupled with the evaluation findings reported here, helped TTAC narrow its technical assistance and training services to several priority areas. These focus areas include strategic planning, basics of tobacco control product development and training, evaluation product development, skill building training, and sustainability planning.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kathleen Miner for her leadership of TTAC and support of this evaluation, and Dearell Niemeyer and Lisa Carlson for their input into the evaluation design. The authors also thank Kim Hiner and Kristen Andrews, who assisted with data collection and preliminary analyses of the qualitative data presented here. Last, the authors thank those who participated in the interviews for their time and many thoughtful contributions to this study.

This study was supported by the American Legacy Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Butterfoss FD. The coalition technical assistance and training framework: helping community coalitions help themselves. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5:118–26. doi: 10.1177/1524839903257262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trohanis PL. Technical assistance and the improvement of services to exceptional children. Theory into Practice. 2001;XXI:119–28. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niemeyer DR, Miner KR, Carlson LM, Hinman JM. Building capacity for success: the Tobacco Technical Assistance Consortium. Health Promot Pract. 2003;4:206–9. doi: 10.1177/1524839903004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Healton CG, Haviland ML, Vargyas E. Will the Master Settlement Agreement achieve a lasting legacy? Health Promot Pract. 2004;5(Suppl 3):12–7. doi: 10.1177/1524839904264579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miner KR, Childers WK, Alperin M, Cioffi J, Hunt N. The MACH model: from competencies to instruction and performance of the public health workforce. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(Suppl 1):9–15. doi: 10.1177/00333549051200S104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thornton AH, Barrow M, Niemeyer D, Burrus B, Gertel AS, Krueger D, et al. Identifying and responding to technical assistance and training needs in tobacco prevention and control. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5(3 Suppl):159–66. doi: 10.1177/1524839904264626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman R, Speers M, McLeroy K, Fawcett S, Kegler M, Parker E, et al. Identifying and defining the dimensions of community capacity to provide a basis for measurement. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25:258–78. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaskin RJ, Brown P, Venkatesh S, Vidal A. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2001. Building community capacity. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norton B, Burdine J, McLeroy K, Felix M, Dorsey A. Community capacity: theoretical roots and conceptual challenges. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research: strategies for improving public health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 194–227. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richards L. Melbourne (Australia): QRS International Party Ltd; Using N6 in qualitative research. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patton M. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2002. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Beverly Hills (CA): Sage Publishing; 1994. Qualitative data analysis: a sourcebook of new methods. [Google Scholar]