Abstract

We report the synthesis of a novel 2′-O-methyl (OMe) riboside phosphoramidite derivative of the G-clamp tricyclic base and incorporation into a series of small steric blocking OMe oligonucleotides targeting the apical stem–loop region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) trans- activation-responsive (TAR) RNA. Binding to TAR RNA is substantially enhanced for certain single site substitutions in the centre of the oligonucleotide, and doubly substituted anti-TAR OMe 9mers or 12mers exhibit remarkably low binding constants of <0.1 nM. G-clamp-containing oligomers achieved 50% inhibition of Tat-dependent in vitro transcription at ∼25 nM, 4-fold lower than for a TAR 12mer OMe oligonucleotide and better than found for any other oligonucleotide tested to date. Addition of one or two OMe G-clamps did not impart cellular trans-activation inhibition activity to cellularly inactive OMe oligonucleotides. Addition of an OMe G-clamp to a 12mer OMe–locked nucleic acid chimera maintained, but did not enhance, inhibition of Tat-dependent in vitro transcription and cellular trans-activation in HeLa cells. The results demonstrate clearly that an OMe G-clamp has remarkable RNA-binding enhancement ability, but that oligonucleotide effectiveness in steric block inhibition of Tat-dependent trans-activation both in vitro and in cells is governed by factors more complex than RNA-binding strength alone.

INTRODUCTION

Oligonucleotide analogues that bind tightly to intracellular RNA targets have found significant application as steric inhibitors of gene expression (1). Mechanistically, such oligonucleotides are directed to bind to locations on cellular RNAs that are known to be recognition sites for proteins or nucleoprotein complexes and to block processes that are essential for gene regulation, such as translational initiation (2), translational elongation (3,4), splicing [reviewed in Mercatante and Kole (5)] or polyadenylation (6). One advantage of this approach is that mishybridisation of a steric block oligonucleotide to an incorrect RNA target, by virtue of partial complementarity, is less likely to lead to undesired gene inactivation than in the case of a similarly mishybridising oligonucleotide in the conventional ‘antisense’ approach, where the oligonucleotide is required to induce cleavage of the target RNA by endogenous RNase H (7).

Since in steric block RNA targeting there is no requirement for RNase H recognition, a range of nucleoside analogues may be introduced throughout the entire oligonucleotide both to prevent degradation by cellular nucleases and to enhance RNA strand invasion and duplex formation. For example, effective steric block was shown in 1997 for a 20mer 2′-O-(methoxethyl) oligoribonucleotide in inhibition of translation initiation of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) mRNA in endothelial cells (2). Other recent examples of steric inhibition of gene expression have utilised analogues such as 2′-O-methyl (OMe) oligoribonucleotides (8–10), morpholino oligonucleotides (10,11), phosphoramidate oligonucleotides (4) or peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) (3,12,13). A recent study has compared a range of different oligonucleotide analogues for steric block use (14).

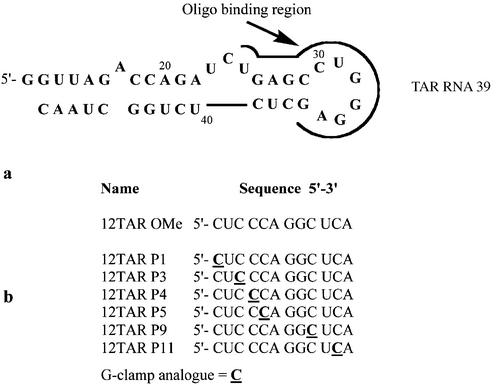

An excellent model system that we and others have used for study of steric block oligonucleotides involves inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Tat-dependent trans-activation [for recent reviews see Karn (15), Taube et al. (16) and Rana and Jeang (17)]. HIV-1 transcriptional elongation is regulated by the trans-activator protein, Tat, that binds to its RNA recognition sequence, TAR, a stem–loop structure that occurs at the 5′-end of all HIV RNA transcripts. Together with a Tat-associated kinase, which includes host cellular factors cyclin T1 and the kinase cdk9, Tat forms a ternary complex with TAR RNA and triggers a hyperphosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II, resulting in stabilisation of the transcription complex and stimulation of full-length transcription. Tat recognition of TAR is localised to a pyrimidine-rich bulge (Fig. 1a) (18), whereas cyclin T1 recognises the apical loop of TAR (19). Since trans-activation is essential for HIV replication, inhibitors that bind TAR and block the action of Tat or its cellular cofactors are potential antiviral agents [for a review of small molecule inhibitors see Wilson and Li (20)] but, disappointingly, no clinical drug candidates have emerged to date.

Figure 1.

(a) Sequence of the HIV-1 TAR RNA 39mer model stem–loop showing the region targeted by oligonucleotides and (b) sequences of the 2′-O-methyl oligoribonucleotides containing single G-clamp analogues.

In our first in vitro steric block studies, we found that OMe oligoribonucleotides of 12–16 residues targeted to the apical stem–loop bound TAR RNA strongly and blocked Tat binding very effectively (21,22). We then showed that such OMe oligoribonucleotides were able to inhibit sequence specifically Tat-dependent in vitro transcription directed by HeLa cell nuclear extract on a DNA template containing the HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) (23,24). Interestingly, a 12mer OMe, a chimeric 12mer OMe containing five 5-methyl C locked nucleic acid (LNA) units, and a 12mer PNA were all equally effective in inhibition of Tat-dependent in vitro transcription, which was attributed to very similar binding strengths to TAR RNA measured under the in vitro transcription conditions (25). The 5′-fluorescein-labelled 12mer OMe–LNA chimeric oligonucleotide, but not its 12mer OMe counterpart, when delivered by cationic lipids into HeLa cells, was able to inhibit sequence-specifically and with dose dependence Tat-dependent HIV LTR trans-activation in a stably integrated plasmid system involving double luciferase reporters (25).

In an independent study, a 15mer PNA targeted to the same apical region of TAR blocked Tat-dependent in vitro transcription and, when electroporated into CEM cells, inhibited HIV LTR-driven chloramphenicol acetyltransferase expression in a transient plasmid reporter system (26). Very recently, 15- and 16mer PNAs were found to be much more effective than 12- and 13mer PNA oligomers targeted to TAR in inhibition of Tat-dependent trans-activation when electroporated into CEM cells in a transient luciferase-based assay (27). The 16mer PNA was most effective in blocking HIV-1 production in a reporter-based infection assay (27). This same 16mer PNA, when disulfide conjugated to a Transportan peptide, was able to penetrate CEM or Jurkat cells and inhibit trans-activation, and also to inhibit virus production in chronically infected H9 cells (28).

An important question in design of steric block oligonucleotides is to what extent enhancement of RNA-binding strength leads to improved biological activity. More specifically, we wished to identify nucleotide analogues that, when incorporated at specific positions, could enhance significantly TAR RNA binding of a steric block oligonucleotide under the buffer conditions used for in vitro transcription and to ask whether such incorporations also lead to improved trans-activation inhibitory activity in vitro and in cells. We had found previously that under transcription conditions, the abilities of 12mer OMe oligonucleotides containing certain nucleoside analogues to invade and bind the structured TAR RNA target differed much less than might have been supposed from the reported strong RNA-binding properties of the analogues. For example, the introduction into the 12mer OMe oligonucleotide of either six 5-propynyl-2′-O-methyl C (29) or five 5-methyl C LNA (30) monomeric units in neither case resulted in significantly enhanced Tat displacement or Tat-dependent transcription inhibition (24). However, one unusual nucleoside analogue seemed particularly worth investigating. The tricyclic cytosine analogue 9-(2-aminoethoxy)-phenoxazine (G-clamp), synthesised as a 2′-deoxynuclesoside, has been shown previously to endow a 2′-deoxyoligonucleotide with remarkably enhanced RNA-binding strength whilst maintaining base specificity towards its complementary target (31). For example, a single G-clamp incorporated into a decamer DNA sequence was found to increase the Tm of its duplex with complementary DNA by 18°C. The G-clamp analogue also imparts a high degree of nuclease resistance to the 3′ termini of oligonucleotides (32). Very recently, G-clamp- containing PNA monomers have been synthesised (33,34) and, when incorporated into PNA oligomers, were reported also to enhance the Tm of its duplex with complementary RNA by up to 18°C (33).

We now report the chemical synthesis of a novel OMe riboside phosphoramidite derivative of the G-clamp tricyclic base and incorporation into a series of OMe oligonucleotides targeting the apical stem–loop region of TAR RNA. We show that binding to both complementary DNA and RNA oligonucleotides and to TAR RNA is remarkably enhanced and that inhibition of Tat-dependent in vitro transcription is increased up to 4-fold, resulting in the most potent oligonucleotide Tat–TAR inhibitors found to date. Specific inhibition of trans-activation in HeLa cells is maintained, but not enhanced, for triple chimeras composed of OMe G-clamp, OMe and LNA units.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

5-Bromouridine was purchased from Pharma-Waldhof GmbH. 1,3-Dichloro-1,1,3,3-tetraisopropyl disiloxane (the Markiewicz reagent) and 4-nitrobenzaldoxime were purchased from Lancaster Synthesis. All other reagents and solvents used in chemical synthesis were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Acetone was distilled over anhydrous calcium sulphate; methanol and ethanol were distilled over magnesium and stored over 4 Å molecular sieves under argon. Pyridine and dichloromethane (DCM) were purchased in their anhydrous form and used as received. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out on pre-coated F254 silica plates, and column chromatography with BDH Silica gel for flash chromatography.

Synthesis of 3-(3′-O-β-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropylphosphoramidyl-5′-O-dimethoxytrityl-2′-O-methyl-β-D-ribofuranosyl)-9-(2-trifluroacetamidoethoxy)-1,3-diaza-2-oxophenoxazine (2′-O-methyl G-clamp, 10)

The synthesis of compound 10 in 10 steps starting from 5-bromouridine (see Scheme 1) is given in full detail in the Supplementary Material. Products were characterised by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometry, TLC, high resolution mass spectrometry and microanalysis where appropriate. The 300 MHz 1H and 121 MHz 31P NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker DRX 300 spectrometer. Chemical shifts (δ) for 1H and 31P are referenced to internal solvent resonances and reported relative to SiMe4 and 85% H3PO4, respectively. High resolution mass spectra were recorded on a Bio-Apex II FT-ICR spectrometer.

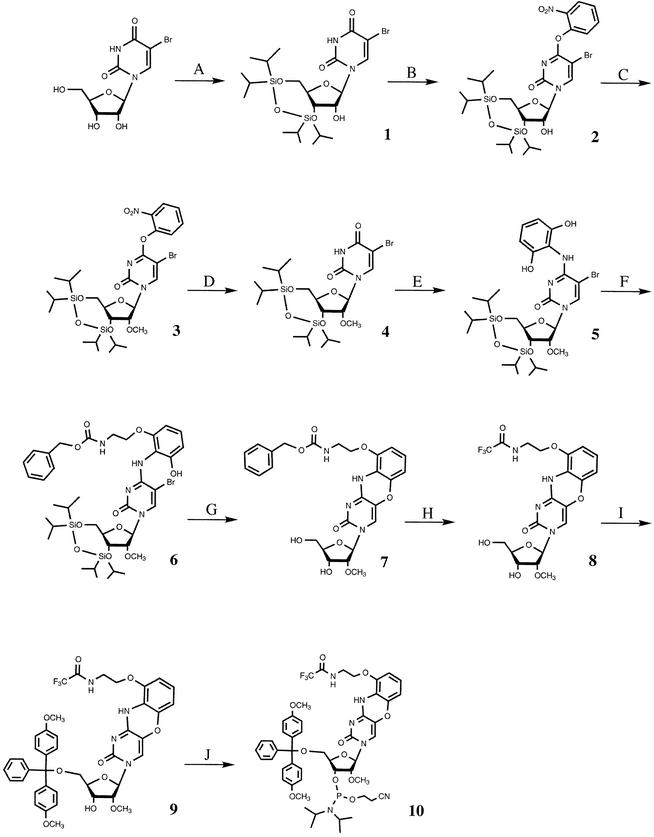

Scheme 1. (A) Markiewicz reagent, pyridine (95% yield). (B) (i) TMSCl, Et3N, DCM; (ii) MesCl, Et3N, DMAP; (iii) o-nitrophenol, DBO; (iv) 2% tosic acid, DCM (83%). (C) MeI, Ag2O, acetone (92%). (D) 4-Nitrobenzaldoxime, tetramethylguanidine, dioxane/water (76%). (E) (i) CCl4, PPh3, DCM; (ii) 2-aminoresorcinol (86%). (F) Benzyl-N-(2-hydroxyethyl)carbamate, DEAD, PPh3 (70%). (G) KF, EtOH (64%). (H) (i) H2, Pd/C, DMF; (ii) ethyltrifluoroacetate, DMAP (72%). (I) DmtCl, pyr. (85%). (J) Phosphitylating agent, DIPEA, DCM (90%).

Oligonucleotide synthesis and characterisation

Oligonucleotide synthesis was carried out on either an ABI 380B or an ABI 394 DNA/RNA synthesiser on a 1 µmol scale using standard synthetic procedures (35). 5-Methyl C LNA amidite was obtained from Proligo, dissolved in acetonitrile:DCM (9:1) and used with standard oligonucleotide synthesis reagents, but with a 15 min coupling time. OMe ribonucleoside amidites were obtained from Transgenomics and used with a 15 min coupling time. The OMe G-clamp amidite (compound 10) was dissolved in acetonitrile and used with a 15 min coupling time. Purifications were carried out by HPLC using a Dionex NucleoPac PA-100 ion-exchange column using a linear gradient of 15–55% buffer B over 20 min (buffer A, 1 mM sodium perchlorate, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 25% formamide; buffer B, 400 mM sodium perchlorate, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 25% formamide). Product eluates were desalted by dialysis. Analytical reversed-phase HPLC was carried out, where necessary, on a Phenomonex Luna C-18 column eluting with a gradient of acetonitrile in 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate buffer pH 7.0. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation-time of flight mass spectra were obtained on a Voyager-DE BioSpectrometry Workstation (PerSeptive Biosystems) in positive ion mode using a 1:1 mixture of 2,6-dihydroxyacetophenone (40 mg ml–1 in MeOH) and aqueous diammonium citrate (80 mg ml–1) as matrix. Thermal melting experiments were carried out on a Perkin Elmer Lambda 40 UV/Vis Spectometer with PTP 6 Peltier Temperature Programmer.

Measurement of oligonucleotide–TAR apparent dissociation constants

Mobility shift experiments and measurement of apparent dissociation constants (Kd) were carried out by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) as previously described (24,25). For the calculation of Kd, the average values from a minimum of three experiments were used.

Inhibition of Tat-dependent in vitro transcription

Tat-dependent in vitro transcription inhibition was carried out as previously described (24,25) from a DNA restriction fragment obtained from a linearised plasmid (10 nM) carrying the HIV-1 LTR in 40 µl reactions containing 15 µl of HeLa cell nuclear extract (36), 80 mM KCl, 2–4 mM MgCl2 (depending on the HeLa nuclear extract), 20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10 µM ZnSO4, 10 mM creatine phosphate, 100 µg ml–1 creatine kinase, 1 µg poly[d(I–C)] (Boehringer Mannheim), 50 µM ATP, GTP and CTP, 5 µM UTP, [γ-32P]UTP (10 µCi), 1 U/µl RNasin (Promega), 200 ng recombinant 1-72 Tat protein (36) and increasing concentrations of inhibitor oligonucleotide. The reactions were incubated at 30°C for 20 min, worked up by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation, and analysed by 6% PAGE containing 7 M urea followed by autoradiography as described previously (24,25).

Inhibition of Tat trans-activation in cells

Inhibition of HIV-1 Tat-mediated trans-activation by oligonucleotide analogues in HeLa cells was carried out as described previously (25), but with some minor changes. Briefly, in each experiment, two identical 96-well plates were prepared with 7500 HeLa Tet-Off/Tat/luc-f/luc-R cells per well and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Oligonucleotides were prepared at a concentration of 1 µM in Opti-MEM serum-free medium, and a 1:1 molar mixture of cationic gemini surfactant GS11 (GSC28) (37) with dioleylphosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE) in water was added to a concentration of 16 µM from a 10 mM stock. After 30 min at room temperature, subsequent dilutions were prepared from the oligonucleotide–GS11 mixture. Cells were incubated with oligonucleotide–GS11 mixtures for 3 h, washed with phosphate-buffered saline and left for additional incubation in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/10% fetal bovine serum for 18 h.

Luciferase assay. Cell lysates were prepared and analysed using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega), and relative light units for both firefly and Renilla luciferase were read sequentially using a Berthold Detection Systems Orion Microplate luminometer. Each data point was averaged over six replicates.

Toxicity assay. The extent of toxicity was determined by measurement of the proportion of live cells colorimetrically using CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Assay (Promega). The absorbance at 490 nm was read using a Molecular Devices Emax Microplate Reader. Each data point was averaged over six replicates.

RESULTS

Chemical synthesis of OMe G-clamp phosphoramidite monomer

The chemical synthesis of the OMe riboside phosphoramidite derivative of the G-clamp base followed a similar route (see Scheme 1) to that devised for the synthesis of the original 2′-deoxy G-clamp (31). However, the first part of the synthesis required the conversion of 5-bromouridine into its OMe derivative. The first step involved use of the Markiewicz silylation reagent for protection of the 5′- and 3′-hydroxyl groups to yield derivative 1 (step A). Then the N-3 group was protected against non-regiospecific alkylation by derivitisation of the O-4 position with an o-nitrophenol protecting group (compound 2, step B) (38). Treatment with methyl iodide and silver (I) oxide catalyst yielded the desired OMe nucleoside derivative 3 in quantitative yield (step C). The o-nitrophenol group was removed by treatment with benzaldoximate anion (compound 4, step D) (39).

The incorporation of 2-aminoresorcinol at the C-4 position was achieved in a one-pot reaction where the base is activated by initial chlorination at the 4-position by treatment with tetrachloromethane followed by substitution with 2-aminoresorcinol (compound 5, step E) (31). The 2-aminoresorcinol was synthesised by catalytic hydrogenation of 2-nitroresorcinol (40). A Mitsunobu reaction using 2-hydroxyethyl phthalimide was able to yield the desired protected ethoxyamine. However, for product solubility reasons, 2-hydroxyethylphthalimide was replaced by N-benzyl-(2-hydroxyethyl) carbamate in the Mitsunobu reaction (compound 6, step F). Removal of the Markiewicz silyl group and ring closure was attempted by use of both base- and fluoride ion-mediated reactions. We found that a single treatment with a large excess of potassium fluoride heated in ethanol could result in both transformations in a one-pot strategy (compound 7, step G). A recent suggestion should be noted that the presence of potassium carbonate in the reaction mixture may improve the yield of such reactions by preventing hydrogen fluoride formation and subsequent debromination at the 5-position of the base (33).

Following ring closure, the CBZ group was removed by hydrogenation and replaced with a trifluoroacetyl group that is more compatible with phosphoramidite synthesis (compound 8, step H). Finally, dimethoxytritylation of the 5′-hydroxyl group (compound 9, step I) and phosphitylation of the 3′-hydroxyl group (step J) yielded the desired phosphoramidite (compound 10) in overall yield of 11.7% for the 10 steps.

DNA- and RNA-binding properties of OMe oligoribonucleotides containing single G-clamp modifications

By use of standard solid-phase phosphoramidite protocols, the OMe G-clamp analogue was incorporated into each of six different positions within a 12mer OMe steric blocking oligonucleotide that we have used previously to target the HIV-1 TAR RNA stem–loop region (Fig. 1b) (24,25). Each oligonucleotide contained a single G-clamp analogue at a position complementary to a guanosine residue in the TAR RNA target.

The stability of duplexes formed by the G-clamp-modified OMe oligonucleotides with their complementary single-stranded DNA or RNA targets was investigated under two salt concentration conditions. Lin and Matteucci (31) reported previously that the position and sequence context of the corresponding 2′-deoxy G-clamp had very little effect on the large increase in binding strength seen in thermal melting experiments, when that analogue was placed within a 2′-deoxyribooligonucleotide sequence and hybridised to a complementary DNA strand. In contrast, duplexes containing an OMe G-clamp analogue showed varied Tm increases ranging from 4 to 17°C compared with the unmodified OMe 12mer, depending on the position of substitution (Table 1). The most stable duplexes were those where the G-clamp analogue was placed in the interior of the oligonucleotide (positions 12TAR OMe P3, P4 and P5). However, there was also some sequence context dependency, since, in 12TAR OMe P4 and P9, the G-clamp is placed equidistant from an end, but P4 shows a higher stability. Duplexes of OMe oligonucleotides with complementary RNA sequences did not show complete melting at the higher salt concentration (140 mM KCl), even at temperatures approaching 100°C, and, therefore, Tm could not be measured accurately. However, at lower salt concentration (20 mM KCl), the increase in Tm against an RNA target for 12TAR OMe P4 and P5 substitution was 15°C in each case. Thus the effect of a single substitution by an OMe G-clamp is an equally dramatic increase in duplex strength to that reported in the 2′-deoxy series, but with significant positional dependence.

Table 1. Binding of 2′-O-methyl oligoribonucleotides containing G-clamp to complementary DNA and RNA oligonucleotides.

| Complementary target | 140 mM KCla | 20 mM KCla | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Sequence 5′–3′ (C = G-clamp analogue) | DNA Tm/°C (ΔTm) | RNA Tm/°C (ΔTm) | DNA Tm/°C (ΔTm) | RNA Tm/°C (ΔTm) |

| 12TAR OMe | 5′-CUC CCA GGC UCA | 64 | 83 | 58 | 79 |

| 12TAR OMe P1 | 5′-CUC CCA GGC UCA | 68 (+4) | >95 | 64 (+6) | 85 (+6) |

| 12TAR OMe P3 | 5′-CUC CCA GGC UCA | 76 (+12) | >95 | 71 (+13) | 90 (+11) |

| 12TAR OMe P4 | 5′-CUC CCA GGC UCA | 80 (+16) | >95 | 75 (+17) | 94 (+15) |

| 12TAR OMe P5 | 5′-CUC CCA GGC UCA | 77 (+13) | >95 | 73 (+15) | 94 (+15) |

| 12TAR OMe P9 | 5′-CUC CCA GGC UCA | 73 (+9) | >95 | 70 (+12) | 87 (+8) |

| 12TAR OMe P11 | 5′-CUC CCA GGC UCA | 72 (+8) | 92 (+9) | 67 (+9) | 88 (+9) |

aTm was measured in the above concentrations of KCl in the presence of 5 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 7.2) and 10 mM MgCl2.

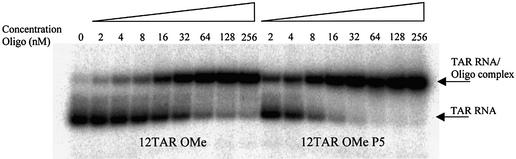

Binding of OMe oligoribonucleotides containing single G-clamp modifications to TAR RNA

The OMe G-clamp-containing oligonucleotides were assayed for their binding strength to the structured TAR RNA model system using a gel mobility shift assay we developed previously (Fig. 2 and Table 2) (21). In general, G-clamp-containing oligonucleotides showed the greatest increases in binding to the model TAR RNA system when the analogue was positioned opposite a guanosine in the TAR loop region (12TAR OMe P4 and P5), which is consistent with the Tm increases seen above for binding to unstructured oligonucleotides. However, under TK80 buffer conditions, when the G-clamp was positioned complementary to a G residue in the stem region of TAR (12TAR OMe P1, P9 or P11), slightly poorer binding was observed compared with the unmodified 12mer OMe oligonucleotide. Under transcription buffer conditions, differences in the Kds between oligonucleotides were much smaller, but the same trends were seen. Once again, the two oligonucleotides having the lowest Kd in transcription buffer were 12TAR OMe P4 and P5, 4- and 6-fold lower, respectively, than without the G-clamp.

Figure 2.

Polyacrylamide gel mobility shift analysis showing binding of oligonucleotide 12TAR OMe and G-clamp-containing 12TAR OMe P5 to 32P-labelled TAR RNA in TK80 buffer.

Table 2. Binding of 2′-O-methyl oligoribonucleotides containing G-clamp to TAR RNA (Kd).

| Sequence name | Kd/nM (TK80)a | Kd/nM (Trans. buffer)b |

|---|---|---|

| 12TAR OMe | 12 ± 1.5 | 3.2 ± 0.7 |

| 12TAR OMe P1 | 20 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 1.6 |

| 12TAR OMe P3 | 6.5 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.4 |

| 12TAR OMe P4 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

| 12TAR OMe P5 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 12TAR OMe P9 | 15 ± 2.0 | 2.4 ± 1.0 |

| 12TAR OMe P11 | 27 ± 1.1 | 3.1 ± 0.7 |

The Kd values were determined by gel mobility shift binding assay.

aTK80 buffer: 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 80 mM KCl.

bTranscription buffer: 20 mM HEPES, 2 mM DTT, 10 µM ZnSO4, 80 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM creatine phosphate.

Multiple G-clamps and effect of combination of G-clamp and LNA modifications

In an attempt to increase further the binding strength of the steric blocking oligonucleotides, a second series of oligonucleotides was synthesised containing multiple G-clamp analogue substitutions. When a 9mer OMe oligonucleotide containing three G-clamp substitutions (UC CCA GGC U) distributed within the molecule was assembled, the product was highly insoluble, resulting in very poor yields, and satisfactory characterisation could not be obtained. Thus we decided to limit incorporation to only two G-clamp analogues (Table 3). The above binding studies had shown that the optimal positions to increase binding affinity were P4 and P5. However, we were concerned that substitution at consecutive positions within the oligonucleotide might result in steric clash when binding to the RNA target. Consequently, the G-clamp analogues were placed 1 nt apart, at positions P3 and P5 (12TAR OMe P3+P5). A shorter 9mer oligonucleotide was also synthesised with a double G-clamp substitution at the same positions (UC CCA GGC U, 9TAR OMe P3+P5). These two oligonucleotides containing two G-clamp substitutions both showed extremely large increases in Tm, beyond the measurable range (>95°C), against both DNA and RNA single-stranded targets (Table 3). Both oligonucleotides bound to TAR RNA with subnanomolar dissociation constants under both buffer conditions, representing a staggering increase in binding of ∼100-fold compared with the unmodified 12TAR OMe (Table 3).

Table 3. Binding of 2′-O-methyl oligoribonucleotides and LNA–OMe chimeras containing G-clamps to TAR RNA (Kd) and to complementary DNA and RNA (Tm).

| Sequence name | Sequence 5′–3′a | Kd/nMb | Kd/nMc | Tmd (ΔTm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA (°C ± 1) | RNA (°C ± 1) | ||||

| 12TAR OMe | 5′-CUC CCA GGC UCA | 12 ± 1.5 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 58 | 79 |

| 12TAR OMe P3+5 | 5′-CUC CCA GGC UCA | 0.2 ± 0.1 | <0.1 | 95 (+37) | >95 |

| 9TAR OMe P3+5 | 5′-UC CCA GGC U | 0.4 ± 0.1 | <0.1 | >95 | >95 |

| 12TAR 7OMe–5LNA | 5′-CUC CCA GGC UCA | 6.6 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 84 (+26) | >95 |

| 12TAR 6OMe–5LNA+P4 | 5′-CUC CCA GGC UCA | 8.6 ± 1.0 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | >95 | >95 |

| 12TAR 7OMe–4LNA+P5 | 5′-CUC CCA GGC UCA | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | >95 | >95 |

The Kd values were determined by gel mobility shift binding assay.

aC = G-clamp analogue; C = LNA.

bIn TK80 buffer: 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 80 mM KCl.

cIn transcription buffer: 20 mM HEPES, 2 mM DTT, 10 µM ZnSO4, 80 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM creatine phosphate.

d20 mM KCl, 5 mM Na2HPO4 pH 7.2, 10 mM MgCl2.

We also synthesised triple chimeric oligonucleotides where a single G-clamp analogue was placed within the 12TAR sequence containing both 5-methyl C LNA and OMe nucleosides, which we had shown previously to inhibit HIV-1 Tat-dependent trans-activation both in vitro and intracellularly (25). The G-clamp analogue was positioned in the oligonucleotide either at P4 (12TAR 6OMe–5LNA+P4) or at P5 (12TAR 7OMe–4LNA+P5) (Table 3). The P4-positioned G-clamp triple chimera showed slightly reduced binding affinity for the TAR RNA target as measured by gel mobility shift assay compared with the 12TAR 7OMe–5LNA oligonucleotide. However, the P5-positioned G-clamp triple chimera showed marginally stronger binding under both salt conditions. Thus the addition of a G-clamp in the context of an LNA–OMe chimera does not give rise to large changes in strength of binding to the structured TAR RNA. In contrast, duplexes formed by the same triple chimeras with unstructured complementary DNA strands showed in both cases very substantial Tm increases (Tms for duplexes with complementary RNA were too high to be measured).

Inhibition of Tat-dependent trans-activation by G-clamp-containing OMe oligoribonucleotides

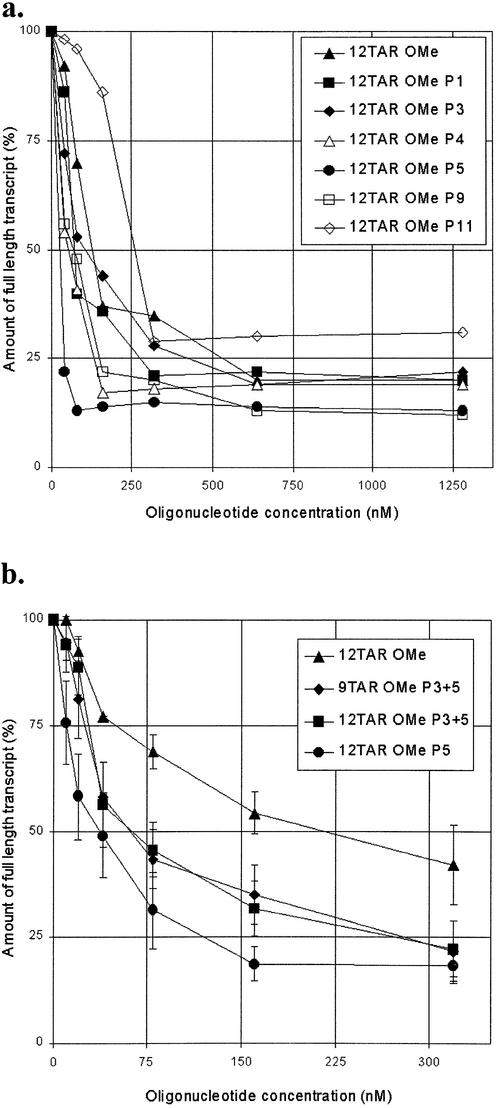

The single G-clamp-substituted OMe oligonucleotides were tested in an HIV Tat-dependent in vitro transcription inhibition assay in the presence of HeLa cell nuclear cell extract that we have described previously (24,25) that makes use of a template DNA containing the HIV promoter including the TAR region. All oligonucleotides showed dose-dependent inhibition of run-off transcription, with 50% inhibition occurring at 25–200 nM oligonucleotide concentration (Fig. 3a). 12TAR P5 showed the greatest inhibition, which correlates with it also being the singly substituted oligonucleotide with the strongest binding to TAR RNA. In further experiments, we compared 12TAR OMe P5 with the doubly substituted G-clamp oligonucleotides 12TAR OMe P3+P5 and 9TAR OMe P3+P5 (Fig. 3b). All three G-clamp-containing oligonucleotides inhibited in vitro transcription 3- to 5-fold better than the unsubstituted 12TAR OMe oligonucleotide. Interestingly, the oligonucleotides containing double G-clamp substitutions were slightly poorer in inhibiting Tat-dependent in vitro transcription than the singly substituted 12TAR P5, despite showing a considerably higher binding affinity for TAR RNA in vitro. These results suggest that binding affinities and in vitro transcription inhibition levels do not fully correlate. Nevertheless, the 12TAR OMe P5 G-clamp oligonucleotide showed the greatest inhibitory power of all oligonucleotides we have tested so far in this assay (50% inhibition at ∼25 nM).

Figure 3.

Oligonucleotide analogue inhibition of Tat-dependent in vitro transcription. Graphs show the amount of full-length transcript as a function of oligomer concentration: (a) all single G-clamp-containing 2′-O-methyl oligonucleotides; (b) oligonucleotide containing two G-clamp analogues compared with 12TAR OMe and 12TAR OMe P5.

Control in vitro transcription experiments under identical conditions but using a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter template (data not shown) showed that the G-clamp-containing oligonucleotides are selective for Tat-dependent in vitro transcription inhibition of the HIV promoter within the concentration range of the above experiments. However, at an oligonucleotide concentration of 2 µM, oligonucleotides containing G-clamp analogues showed ∼50% reduction of the amount of the full-length transcript. 9TAR OMe P3+P5 showed 50% inhibition of CMV-driven transcription at ∼500 nM.

12TAR OMe P5, 12TAR OMe P3+P5 and 9TAR OMe P3+P5 were tested for their abilities to inhibit Tat-dependent trans-activation in HeLa cells using a double luciferase reporter system containing three stably integrated plasmids that we reported previously (25). This assay allows the effect of the oligonucleotide to be monitored for specific inhibition of transcription/translation driven from a plasmid containing the HIV promoter (firefly luciferase) compared with a plasmid containing the constitutive CMV promoter (expressing Renilla luciferase). In these cells, HIV-1 Tat protein is expressed from the Tet-OFF promoter contained within the third plasmid. One advantage of this cell line is that inhibitors can be tested directly on cells without the need for plasmid co-transfection.

For the delivery of oligonucleotides into cells, we used the gemini surfactant, GS11, as a 1:1 molar ratio with DOPE (37), which we have found to be as effective as cationic lipid for delivery of OMe–LNA chimeric oligonucleotides but is less toxic (see below and A.A.Arzumanov and M.J.Gait, unpublished data). Despite significant increases in the ability to inhibit in vitro transcription in HeLa cell nuclear extract, none of the three tested OMe oligonucleotides containing single or double G-clamps showed any inhibition of firefly luciferase expression in HeLa cells up to 1 µM concentration, nor of the control Renilla luciferase (data not shown). Thus the addition of G-clamp residues does not impart cellular activity to the 12TAR OMe oligonucleotide, which we showed previously to be inactive in this test system (25).

Inhibition of Tat-dependent trans-activation by triple chimeras of G-clamp, LNA and OMe oligoribonucleotides

12TAR 6OMe–5LNA+P4 and 12TAR 7OMe–4LNA+P5 were tested for their abilities to inhibit in vitro Tat-dependent transcription in the presence of HeLa cell nuclear extract. It was found that neither of these showed significant increases in transcription inhibition compared with the 12TAR 7OMe– 5LNA (data not shown), which we have reported previously to display a 50% inhibition at 100–200 nM. These results are in line with the only marginally altered in vitro binding strengths to the structured TAR RNA target.

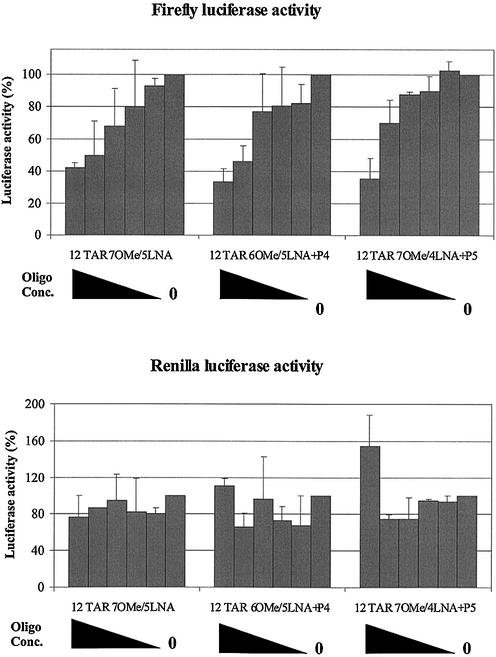

Triple chimeras 12TAR 6OMe–5LNA+P4 and 12TAR 7OMe–4LNA+P5 were tested in the HeLa cell double luciferase assay and were both shown to be able to reduce firefly luciferase expression in a dose-dependent manner, but neither had any effect on Renilla luciferase activity (Fig. 4). The levels of activity were similar to that observed for 12TAR 7OMe–5LNA (50% inhibition at 100–200 nM). These results show that there is no gain of intracellular trans-activation inhibition activity by insertion of a OMe G-clamp, neither is such activity lost. No cellular toxicity was observed using a standard MTT assay for concentrations up to 1 µM of these single G-clamp-containing oligonucleotides delivered by GS11/DOPE (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effect of oligonucleotide analogues delivered by the cationic surfactant GS11 on HeLa Tet-Off/Tat/luc-f/luc-R cells. 12TAR 7OMe–5LNA, 12TAR 6OMe–5LNA+P4 and 12TAR 7OMe–4LNA+P5 concentrations are shown as a black wedge from left to right: 1000, 500, 250, 125, 62.5 and 0 nM, respectively.

DISCUSSION

A great deal of effort has been expended by numerous laboratories over many years aimed at the discovery of nucleic acids analogues that bind more strongly to RNA targets in vitro than natural DNA or RNA oligonucleotides and which at the same time are nuclease resistant. Our range of assays involving the HIV-1 TAR RNA stem–loop allows us to address the question of to what extent enhancements in binding strength in vitro correlate with improved abilities to inhibit Tat-dependent trans-activation both in the presence of HeLa cell extract and in live HeLa cells. The in vitro transcription inhibition assay is particularly valuable in that the ability of the oligonucleotide to compete with the active transcriptional machinery at the TAR target can be assessed without the added complication of requiring delivery into the right cellular compartment, in this case the nucleus.

We previously have studied several nucleotide analogues that are known for their strong RNA-binding properties when incorporated into oligonucleotides (24,25). We showed that targeting of the TAR apical loop and stem by 12mer oligonucleotides was sufficient to disrupt Tat binding to the bulge of TAR and inhibited Tat-induced trans-activation. For example, 12mers consisting of OMe, OMe–LNA chimera or PNA behaved similarly in inhibition of Tat-dependent transcription, with 50% inhibition at 100–200 nM. It was found that under the buffer conditions of transcription (20 mM HEPES, 2 mM DTT, 10 µM ZnSO4, 80 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM creatine phosphate), strengths of binding to the structured TAR RNA target hardly varied (Kd values were all 2–3 nM), in contrast to under low salt conditions (20 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4) where OMe, OMe–LNA and PNA oligonucleotides had vastly different Kd values of 61, 25 and 1 nM, respectively. Therefore, under these highly stringent conditions, to be able to reduce further the concentration required for inhibition of transcription, an oligonucleotide analogue must have exceptionally strong TAR RNA-binding potential in order to compete significantly more effectively with the transcriptional machinery.

Of all the oligonucleotide analogues we have tested to date, the OMe G-clamp oligonucleotide 12TAR OMe P5 and the double G-clamp-containing oligonucleotides 12TAR OMe P3+P5 and 9TAR OMe P3+P5 inhibit Tat-dependent in vitro transcription 3- to 4-fold more strongly than any others; 12TAR OMe P5 showed a remarkable 50% inhibition at 25 nM. It should be noted in comparison that the strongest TAR-binding selected aptamer to date constructed of OMe ribonucleotides was able to inhibit in vitro transcription by 50% at only ∼400 nM (41).

Why has it been so hard to obtain oligonucleotide analogues that inhibit Tat-dependent in vitro transcription by 50% at better than 100 nM? The mechanism of trans-activation is complex, but an important trigger has been shown to involve the co-ordinated binding of Tat and cyclin T1 to the apical stem–loop of TAR with a Kd of 0.4 nM (42). The G-clamp-containing OMe oligonucleotides are in principle more than adequate to compete with this ternary interaction (Kd of 0.2 nM for the P5-substituted OMe oligonucleotide under transcription conditions) if this were an equilibrium process. However, this inhibition is clearly not an equilibrium process but instead must involve a dynamic competition with the transcription machinery. We are therefore pleased with the achievement of ∼25 nM for 50% inhibition of in vitro transcription for the OMe P5 G-clamp oligonucleotide.

A clue to improving the effectiveness of inhibition further lies in measurement of the Kon and Koff rates under transcription conditions. Preliminary measurements with naked TAR RNA suggest that 12TAR OMe P3+P5, for example, has a 4-fold slower off rate (1 ± 0.2 × 10–3 s–1, data not shown) than that we have reported for 12TAR OMe (25), whereas the on rate is only ∼2-fold slower. More detailed rate analysis of a range of analogues will be necessary to establish the significance of this preliminary result. So far, we have been unable to measure the on and off rates satisfactorily in the presence of HeLa cell nuclear extract, which would be the most revealing. However, if transcriptional inhibition activity is limited by the off rate, then for any further improvements it may be necessary to devise analogues that utilise principles of interaction quite different to those commonly looked for to gain RNA-binding strength (increased base stacking, RNA-like sugar configuration, etc.). For example, it may be useful to lock the RNA into an oligonucleotide-bound conform ation, e.g. by cross-linking with a transplatin-modified oligonucleotide (43).

We have shown previously that 12TAR OMe is inactive in our cellular trans-activation assay when formulated with cationic lipid (25) or GS11 surfactant, due to its poor cellular penetration (A.A.Arzumanov and M.J.Gait, unpublished results). We have shown here that addition of one or two G-clamp units was unable to effect cellular activity. It is likely that G-clamp modifications do not assist oligonucleotides in either cellular uptake or release from endosomes. We are unaware of any other reports of cellular activity of oligonucleotides containing G-clamps which do not in addition contain phosphorothioate linkages, for example (44).

We found that addition of alternating phosphorothioates to the 12TAR OMe resulted in non-specific reduction of constitutive Renilla luciferase expression in addition to Tat-dependent firefly luciferase expression in HeLa cells, but we were able instead to generate substantial specific reduction of firefly luciferase activity with the chimeric 12TAR 7OMe– 5LNA oligonucleotide (25) (see also Fig. 4). Disappointingly, when an OMe G-clamp unit was introduced in either of two positions into the OMe–LNA chimera, the substantial enhancement of TAR RNA binding afforded by the G-clamp analogue to OMe oligonucleotides was not maintained (Table 3). Thus no significant reduction was seen in the 50% inhibition of in vitro transcription. It was gratifying to observe that the substantial cellular activity of 12TAR 7OMe–5LNA was not lost upon incorporation of a G-clamp in either position P4 or P5 (Fig. 4). No increase in cellular activity would be expected bearing in mind the unaltered in vitro transcription inhibition data for the triple chimeras containing G-clamps. These results show that the combination of sugar-modified LNA units with base-modified G-clamp, at least in the particular juxtaposed sites chosen, does not allow the substantial binding benefit of the G-clamp unit to be manifest. It is not clear if any further G-clamp triple chimera experiments involving LNA units would substantially alter this outcome, since the structural basis for the lack of binding additivity is likely to be complex and would require extensive biophysical or structural studies. However, our studies are reassuring that sites within the OMe–LNA chimeras are tolerant of modification without loss of cellular activity. The challenge for the future in studies of steric block interference of cellular RNA function will be to search for suitable combinations of analogues that lock the RNA target into its oligonucleotide-bound form, whilst maintaining, or preferably enhancing, the cellular delivery and activity.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at NAR Online.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Donna Williams for oligonucleotide synthesis, Mohinder Singh for technical assistance, and Dmitri Stetsenko, Andrey Malakhov, Birgit Verbeure and David Loakes for helpful discussions. GS11 (GSC28) was kindly supplied by Tony Kirby (University of Cambridge) and Patrick Camilleri (Glaxo Smith Kline).

REFERENCES

- 1.Toulmé J.J. (2001) New candidates for true antisense. Nat. Biotechnol., 19, 17–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker B.F., Lot,S.S., Condon,T.P., Cheng-Flourney,S., Lesnik,E.A., Sasmor,H.M. and Bennett,C.F. (1997) 2′-O-(2-methoxy)ethyl-modified anti-intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) oligonucleotides selectively increase the ICAM-1 mRNA level and inhibit formation of the ICAM-1 translation initiation complex in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 11994–12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dias N., Dheur,S., Nielsen,P.E., Gryaznov,S., Van Aerschot,A., Herdewijn,P., Hélène,C. and Saison-Behmoaras,T.E. (1999) Antisense PNA tridecamers targeted to the coding region of Ha-ras mRNA arrest polypeptide chain elongation. J. Mol. Biol., 294, 403–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faria M., Spiller,D.G., Dubertret,C., Nelson,J.S., White,M.R.H., Scherman,D., Hélène,C. and Giovannangeli,C. (2001) Phosphoramidate oligonucleotides as potent antisense molecules in cells and in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol., 19, 40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercatante D.R. and Kole,R. (2002) Control of alternative splicing by antisense oligonucleotides as a potential chemotherapy: effects on gene expression. Biochim. Biophys Acta, 1587, 126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vickers T.A., Wyatt,J.R., Burckin,T., Bennett,C.F. and Freier,S.M. (2001) Fully modified 2′-MOE oligonucleotides redirect polyadenylation. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 1293–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monia B.P., Lesnik,E.A., Gonzalez,C., Lima,W.F., McGee,D., Guinosso,C.J., Kawasaki,A.M., Cook,P.D. and Freier,S.M. (1993) Evaluation of 2′-modified oligonucleotides containing 2′-deoxy gaps as antisense inhibitors of gene expression. J. Biol. Chem., 268, 14514–14522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mann C.J., Honeyman,K., Cheng,A.J., Ly,T., Lloyd,F., Fletcher,S., Morgan,J.E., Partridge,T.A. and Wilton,S.D. (2001) Antisense-induced exon skipping and synthesis of dystrophin in the mdx mouse. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmitz J.C., Yu,D., Agrawal,S. and Chu,E. (2001) Effect of 2′-O-methyl antisense ORNs on expression of thymidylate synthase in human colon cancer RKO cells. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 415–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmajuk G., Sierakowska,H. and Kole,R. (1999) Antisense oligonucleotides with different backbones. Modification of splicing pathways and efficacy of uptake. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 21783–21789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giles R.V., Spiller,D.G., Clark,R.E. and Tidd,D.M. (1999) Antisense morpholino oligonucleotide analog induces missplicing of C-myc mRNA. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev., 9, 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doyle D.F., Braasch,D.A., Simmons,C.G., Janowski,B.A. and Corey,D.R. (2001) Inhibition of gene expression inside cells by peptide nucleic acids: effect of mRNA target sequence, mismatched bases and PNA length. Biochemistry, 40, 53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karras J.G., Maier,M.A., Watt,A. and Manoharan,M. (2001) Peptide nucleic acids are potent modulators of endogenous pre-mRNA splicing of the murine interleukin-5 receptor-α chain. Biochemistry, 40, 7853–7859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sazani P., Kang,S.-H., Maier,M.A., Wei,C., Dillman,J., Summerton,J., Manoharan,M. and Kole,R. (2001) Nuclear antisense effects of neutral, anionic and cationic analogs. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 3965–3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karn J. (1999) Tackling Tat. J. Mol. Biol., 293, 235–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taube R., Fujinaga,K., Wimmer,J., Barboric,M. and Peterlin,B.M. (1999) Tat transactivation: a model for the regulation of eukaryotic transcriptional elongation. Virology, 264, 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rana T.M. and Jeang,K.-T. (1999) Biochemical and functional interactions between HIV-1 Tat protein and TAR RNA. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 365, 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dingwall C., Ernberg,I., Gait,M.J., Green,S.M., Heaphy,S., Karn,J., Lowe,A.D., Singh,M. and Skinner,M.A. (1990) HIV-1 tat protein stimulates transcription by binding to a U-rich bulge in the stem of the TAR RNA structure. EMBO J., 9, 4145–4153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richter S., Cao,H. and Rana,T.M. (2002) Specific HIV-1 TAR RNA loop sequence and functional groups are required for human cyclin T1–Tat–TAR ternary complex formation. Biochemistry, 41, 6391–6397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson W.D. and Li,K. (2000) Targeting RNA with small molecules. Curr. Med. Chem., 7, 73–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mestre B., Arzumanov,A., Singh,M., Boulmé,F., Litvak,S. and Gait,M.J. (1999) Oligonucleotide inhibition of the interaction of HIV-1 Tat protein with the trans-activation responsive region (TAR) of HIV RNA. Biochim. Biophys Acta, 1445, 86–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arzumanov A. and Gait,M.J. (1999) Inhibition of the HIV-1 Tat protein–TAR RNA interaction by 2′-O-methyl oligoribonucleotides. In Holy,A. and Hocek,M. (eds), Collection Symposium Series. Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. Vol. 2, pp. 168–174.

- 23.Arzumanov A., Walsh,A.P., Liu,X., Rajwanshi,V.K., Wengel,J. and Gait,M.J. (2000) XIV International Round Table. Nucleosides, Nucleotides and Their Biological Applications. International Medical Press, San Francisco.

- 24.Arzumanov A., Walsh,A.P., Liu,X., Rajwanshi,V.K., Wengel,J. and Gait,M.J. (2001) Oligonucleotide analogue interference with the HIV-1 Tat protein–TAR RNA interaction. Nucl. Nucl., 20, 471–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arzumanov A., Walsh,A.P., Rajwanshi,V.K., Kumar,R., Wengel,J. and Gait,M.J. (2001) Inhibition of HIV-1 Tat-dependent trans-activation by steric block chimeric 2′-O-methyl/LNA oligoribonucleotides. Biochemistry, 40, 14645–14654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayhood T., Kaushik,N., Pandey,P.K., Kashanchi,F., Deng,L. and Pandey,V.N. (2000) Inhibition of Tat-mediated transactivation of HIV-1 LTR transcription by polyamide nucleic acid targeted to the TAR hairpin element. Biochemistry, 39, 11532–11539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaushik M.J., Basu,A. and Pandey,P.K. (2002) Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by anti-transactivation responsive polyamide nucleotide analog. Antiviral Res., 56, 13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaushik N., Basu,A., Palumbo,P., Nyers,R.L. and Pandey,V.N. (2002) Anti-TAR polyamide nucleotide analog conjugated with a membrane-permeating peptide inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type I production. J. Virol., 76, 3881–3891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Froehler B.C., Wadwani,S., Terhorst,T.J. and Gerrard,S.R. (1992) Oligodeoxynucleotides containing C-5 propyne analogs of 2′-deoxyuridine and 2′-deoxycytidine. Tetrahedron Lett., 33, 5307–5310. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koshkin A.A., Singh,S.K., Nielsen,P., Rajwanshi,V.K., Kumar,R., Meldgaard,M., Olsen,C.E. and Wengel,J. (1998) LNA (locked nucleic acids): synthesis of the adenine, cytosine, guanine, 5-methylcytosine, thymine and uracil bicyclonucleoside monomers, oligomerisation and unprecedented nucleic acid recognition. Tetrahedron, 54, 3607–3630. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin K.-Y. and Matteucci,M. (1998) A cytosine analogue capable of clamp-like binding to a guanine in helical nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 120, 8531–8532. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maier M.A., Leeds,J.M., Balow,G., Springer,R.H., Bharadwaj,R. and Manoharan,M. (2002) Nuclease resistance of oligonucleotides containing the tricyclic cytosine analogues phenoxazine and 9-(2-aminoethoxy)-phenoxazine (‘G-clamp’) and origins of their nuclease resistance properties. Biochemistry, 41, 1323–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rajeev K.G., Maier,M.A., Lesnik,E.A. and Manoharan,M. (2002) High-affinity peptide nucleic acid oligomers containing tricyclic cytosine analogues. Org. Lett., 4, 4395–4398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ausin C., Ortega,J.-A., Robles,J., Grandas,A. and Pedroso,E. (2002) Synthesis of amino- and guanidino-G-clamp PNA monomers. Org. Lett., 4, 4073–4075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown T. and Brown,D.J.S. (1991) Modern machine-aided methods of oligodeoxyribonucleotide synthesis. In Eckstein,F. (ed.), Oligonucleotides and Analogues: A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 1–24.

- 36.Rittner K., Churcher,M.J., Gait,M.J. and Karn,J. (1995) The human immunodeficiency virus long terminal repeat includes a specialised initiator element which is required for Tat-responsive transcription. J. Mol. Biol., 248, 562–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGregor C., Perrin,C., Monck,M., Camilleri,P. and Kirby,A.J. (2001) Rational approaches to the design of cationic gemini surfactants for gene delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 26, 6215–6220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nyilas A. and Chattopadhyaya,J. (1986) Synthesis of O2′-methyluridine, O2′-methylcytidine, N4,O2′-dimethylcytidine and N4,N4,O2′-trimethylcytidine from a common intermediate. Acta Chem. Scand., 40, 826–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reese C.B., Titmas,R.C. and Yau,L. (1978) Oximate ion unblocking of oligonucleotide phosphotriester intermediates. Tetrahedron Lett., 19, 2727–2730. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wai J.S., Williams,T.M., Bamberger,D.L., Fisher,T.E., Hoffman,J.M., Hudcosky,R.J., Mactough,S.C., Rooney,C.S., Saari,W.S., Thomas,C.M. et al. (1993) Synthesis and evaluation of 2-pyridinone derivatives as specific HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors. 3. Pyridyl and phenyl analogs of 3-aminopyridin-2(1H)-one. J. Med. Chem., 36, 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Darfeuille F., Arzumanov,A., Gait,M.J., Di Primo,C. and Toulmé,J.J. (2002) 2′-O-methyl RNA hairpins generate loop–loop complexes and selectively inhibit HIV-1 Tat-mediated transcription. Biochemistry, 41, 12186–12192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J., Tamilarisu,N., Hwang,S., Garber,M.E., Huq,I., Jones,K.A. and Rana,T.M. (2000) HIV-1 TAR RNA enhances the interaction between Tat and cyclin T1. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 34314–34319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aupeix-Scheidler K., Chabas,S., Bidou,L., Rousset,J.-P., Leng,M. and Toulmé,J.J. (2000) Inhibition of in vitro and ex vivo translation by a transplatin-modified oligo(2′-O-methylribonucleotide) directed against the HIV-1 gag–pol frameshift signal. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 438–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flanagan W.M., Wagner,R.W., Grant,D., Lin,K.-Y. and Matteucci,M. (1999) Cellular penetration and antisense activity by a phenoxazine-substituted heptanucleotide. Nat. Biotechnol., 17, 48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.