Abstract

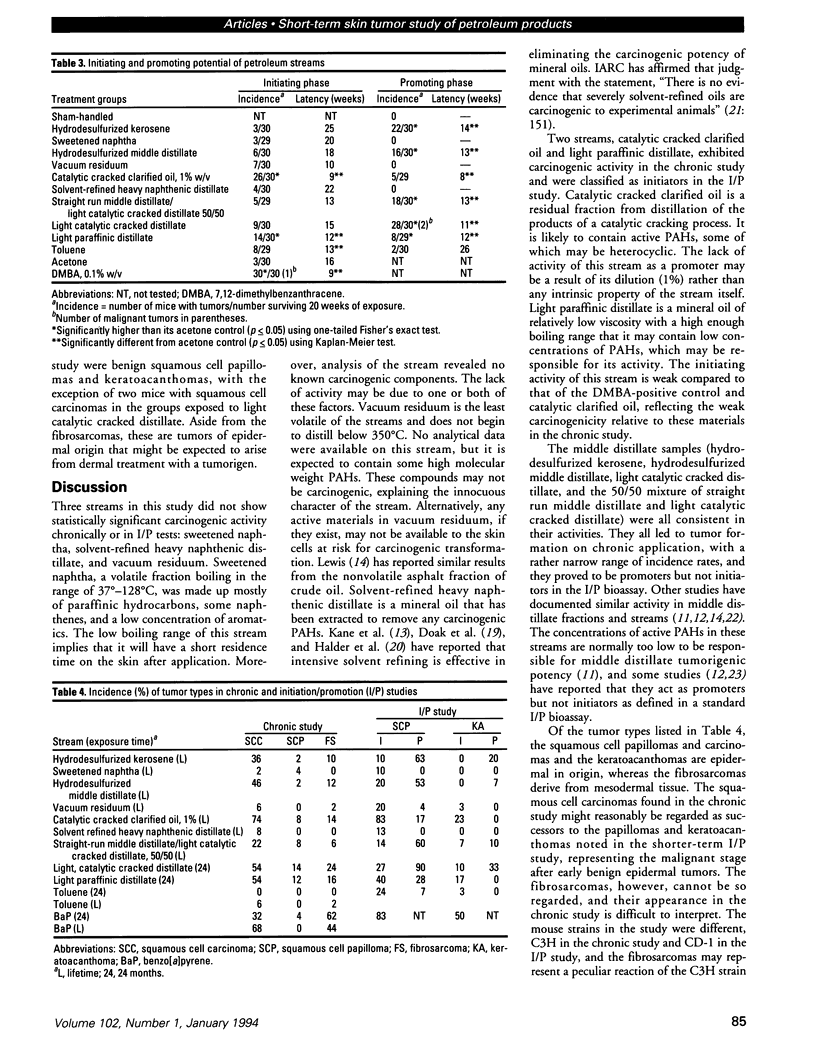

Nine refinery streams were tested in both chronic and initiation/promotion (I/P) skin bioassays. In the chronic bioassay, groups of 50 C3H/HeJ mice received twice weekly applications of 50 microl of test article for at least 2 years. In the initiation phase of the I/P bioassay, groups of CD-1 mice received an initiating dose of 50 microl of test article for 5 consecutive days, followed by promotion with 50 microl of phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (0.01% w/v in acetone) for 25 weeks. In the promotion phase of the I/P bioassay, CD-1 mice were initiated with 50 microl of 7,12-dimethylbenzanthracene (0.1% w/v in acetone) or acetone, followed by promotion with 50 microl of test article twice weekly for 25 weeks. The most volatile of the streams, sweetened naphtha, and the least volatile, vacuum residuum, were noncarcinogenic in both assays. Middle distillates, with a boiling range of 150 degrees-370 degreesC, demonstrated carcinogenic activity in the chronic bioassay and acted as promoters but not initiators in the I/P bioassay. Untreated mineral oil streams displayed initiating activity and were carcinogenic in the chronic bioassay, presumably due to the presence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons of requisite size and structure. A highly solvent-refined mineral oil stream lacked initiating activity. These results indicate that the I/P bioassay, which takes 6 months to complete, may be a good qualitative predictor of the results of a chronic bioassay, at least for petroleum streams. Furthermore, the I/P bioassay can provide insight into possible mechanisms of tumor development.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Biles R. W., McKee R. H., Lewis S. C., Scala R. A., DePass L. R. Dermal carcinogenic activity of petroleum-derived middle distillate fuels. Toxicology. 1988 Dec 30;53(2-3):301–314. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(88)90222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. M., Ellwein L. B. Cell proliferation in carcinogenesis. Science. 1990 Aug 31;249(4972):1007–1011. doi: 10.1126/science.2204108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doak S. M., Brown V. K., Hunt P. F., Smith J. D., Roe F. J. The carcinogenic potential of twelve refined mineral oils following long-term topical application. Br J Cancer. 1983 Sep;48(3):429–436. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1983.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellwein L. B., Cohen S. M. Simulation modeling of carcinogenesis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992 Mar;113(1):98–108. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(92)90013-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart J. M., Hatoum N. S., Halder C. A., Warne T. M., Schmitt S. L. Tumor initiation and promotion effects of petroleum streams in mouse skin. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1988 Jul;11(1):76–90. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(88)90272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder C. A., Warne T. M., Little R. Q., Garvin P. J. Carcinogenicity of petroleum lubricating oil distillates: effects of solvent refining, hydroprocessing, and blending. Am J Ind Med. 1984;5(4):265–274. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700050403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane M. L., Ladov E. N., Holdsworth C. E., Weaver N. K. Toxicological characteristics of refinery streams used to manufacture lubricating oils. Am J Ind Med. 1984;5(3):183–200. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S. C. Crude petroleum and selected fractions. Skin cancer bioassays. Prog Exp Tumor Res. 1983;26:68–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee R. H., Plutnick R. T., Przygoda R. T. The carcinogenic initiating and promoting properties of a lightly refined paraffinic oil. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1989 May;12(4):748–756. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(89)90006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolgavkar S. H., Knudson A. G., Jr Mutation and cancer: a model for human carcinogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981 Jun;66(6):1037–1052. doi: 10.1093/jnci/66.6.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skisak C. The role of chronic acanthosis and subacute inflammation in tumor promotion in CD-1 mice by petroleum middle distillates. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1991 Jul;109(3):399–411. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(91)90003-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaga T. J. Overview of tumor promotion in animals. Environ Health Perspect. 1983 Apr;50:3–14. doi: 10.1289/ehp.83503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witschi H. P., Smith L. H., Frome E. L., Pequet-Goad M. E., Griest W. H., Ho C. H., Guerin M. R. Skin tumorigenic potential of crude and refined coal liquids and analogous petroleum products. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1987 Aug;9(2):297–303. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(87)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]