Abstract

Sections from all spinal cord levels from 20 human fetuses, age range 7.5–17 gestational weeks (GW) were immunostained for non-phosphorylated neurofilaments (to reveal motoneurones, spinocerebellar neurones and other large neurones), the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin (large proprioreceptive afferents), growth-associated protein 43 kDa (growing axons), glial fibrillary acidic protein (radial glia), synaptophysin (synaptic terminals) the cell–cell recognition molecule ephrin A4 (EphA4) and the ETS transcription factor Er81 (subclasses of motoneurone and proprioreceptive neurone). Muscle afferents crossed the dorsal horn by 7.5 GW and innervated motoneurones by 9 GW. An alignment of glial fibres guided them from dorsal columns to ventral horn, at right angles to the radial glia. They continued to provide a dense innervation of motoneurone pools up to 17 GW. By 13 GW motoneurones were segregated into distinct columns, all of which expressed EphA4 although only certain lateral groups expressed Er81. However, Er81 expression was more widespread amongst dorsal root ganglion neurones. From 9 GW Clarke's column neurones were identified and by 14 GW were heavily innervated by parvalbumin-positive afferents whilst their efferent axons could be traced to the lateral funiculus. This investigation contributes towards a timetable for the functional development of human motor control and makes comparisons with well-studied rodent models.

Keywords: EphA4, Er81, motoneurone, parvalbumin, proprioreceptive afferents

Introduction

A vast amount of data has been gathered concerning spinal cord development in lower vertebrates and mammals, both descriptive and arising from experimental manipulations, the hope being that we can understand better the normal organization and development of the human spinal cord and thus devise remedies for developmental motor disorders or spinal cord injury in later life. In order to relate theories derived from animal experiments to human development it is necessary first to provide a description of human development. With only a few exceptions, attempts to do this have relied upon studies of paraffin sections using traditional techniques such as Nissl, myelin and silver stains (e.g. Altman & Bayer, 2001). The present study employed immunohistochemical techniques in frozen sections directed at marker proteins that not only reveal the structure of the spinal cord but also the functional state and degree of differentiation of the cells expressing these proteins. For instance, the calcium binding protein parvalbumin (PV) has not only proved to be a highly reliable marker for large-diameter primary sensory afferents during spinal cord development (Zhang et al. 1990; Clowry et al. 1997) but its functional role as a calcium buffer reveals high levels of electrical activity in the neurones or axons that express it (Solbach & Celio, 1991). The monoclonal antibody SMI-32 recognizes non-phosphorylated neurofilaments (NPNFs), a robust marker for motoneurones and other large neurones in the adult spinal cord of a number of species (Tsang et al. 2000). The present study investigated its value as a marker of such cells in developing spinal cord. NPNFs are essential for maintaining the structure and transport capability of large dendrites and axons (Lee & Cleveland, 1994).

Growth-associated protein 43 kDa (GAP43) is concentrated in growing axons and their growth cones and shows where new axonal pathways are being formed (Benowitz & Routtenberg, 1997). Synaptophysin is a synaptic vesicle-associated protein that shows where new axons are forming synapses (Wiedenmann & Franke, 1985; Leclerc et al. 1989). Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) is a cytoskeletal protein expressed by both radial glia and immature astrocytes in the primate brain (Levitt & Rakic, 1980). Immunohistological examination of GFAP expression reveals the morphology of astrocytes which, in turn, reveals their degree of differentiation. Immature elongated radial glia guide cell migration whilst stellate astrocytes have metabolic functions in the mature central nervous system (Chanas-Sacre et al. 2000).

How motoneurones find their precise location in the spinal cord, how they grow their axons to their targets and how they control the origin of synapses upon them is only partly understood. However, animal experiments have revealed that different motoneurone pools express combinations of different transcription factors which, in turn, control expression of cell–cell recognition molecules that guide outgrowth of axons and axon–target recognition in the spinal cord. The ETS gene Er81 is expressed by subsets of motoneurones in chick and mouse spinal cord and may control specific synapse formation between muscle spindle afferents and motoneurones (Lin et al. 1998). In the rodent, the ephrin A4 receptor (EphA4) is expressed by motoneurones and other neurones in the rodent intermediate and ventral horn prenatally (Coonan et al. 2001). In the periphery it is involved in guiding motor axons to their appropriate target muscles (Eberhart et al. 2002; Kania & Jessell, 2003). In the spinal cord it prevents the abnormal decussation of certain axon pathways by an inhibitory interaction with ephrin B3 (Coonan et al. 2001; Kullander et al. 2003). Whether or not the same mechanisms might be operating in human development has not been addressed.

The present study is based on samples of spinal cord from 20 fetuses ranging in age from 7.5 to 17 gestational weeks (GW) and represents the time period from when movements in the human fetus change from whole head and body movements to independent limb movements (De Vries et al. 1982) up to the time when the corticospinal tract begins to grow into the spinal cord (Altman & Bayer, 2001).

Materials and methods

Samples of spinal cord from multiple levels were taken from 20 fetuses ranging in age from 7.5 to 17 GW (same as post-conceptional age). Age was estimated from measurements of foot length and heel to knee length. These were compared with a standard growth chart (Hern, 1984). This was considered more reliable than relying on reporting of weeks post-menstruation. Samples were taken from aborted fetuses arising from social terminations with maternal permission and the approval of the Newcastle University Hospitals Ethical Review Committee and Newcastle Human Developmental Resource Bank. Vertebral column containing spinal cord was taken within 2 h of delivery and immersion fixed for 24 h in 0.1 m phosphate-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde solution at 37 °C prior to dissection of the spinal cord from the surrounding bones. The spinal cord was further fixed for at least 24 h at 4 °C prior to transfer to 30% sucrose in 0.1 m phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for cryoprotection for at least another 24 h. Transverse sections (50 µm) were cut using a freezing microtome and the sections placed in PBS prior to immunostaining. In two cases the entire vertebral column was sectioned transversely.

Immunocytochemistry

For immunoperoxidase labelling, sections were incubated free-floating with gentle agitation overnight at 4 °C in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBST), 3% of the appropriate blocking serum (Vector Laboratories) and one of the following primary antibodies: anti-parvalbumin monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Alldrich, diluted 1 : 5000), anti-nonphosphorylated neurofilament monoclonal antibody (clone SMI-32, Sternberger monoclonals, 1 : 1000), anti-GFAP rabbit polyclonal antibody (Sigma-Alldrich, 1 : 400) anti-GAP43 monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Alldrich, 1 : 1000), anti-synaptophysin monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Alldrich, 1 : 500), anti-EPH4AR rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotech, 1 : 4000, see Bianchi & Gale, 1998) and anti-Er81 rabbit polyclonal antibody (a gift from Dr T. Jessell, 1 : 20 000). Following washing in PBS sections were incubated for a further 2 h at room temperature with the appropriate biotinylated secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories, diluted 1 : 200 in PBST), washed and then incubated for a further 1 h at room temperature with streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (Vector Laboratories, diluted 1 : 200 in PBST). Sections were washed in PBS and then reacted with 0.05% diaminobenzidine (Sigma) and 0.003% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for up to 20 min. After further washing sections were mounted on gelatinized slides, air-dried, cleared and mounted in Entellan (Merck). Images were captured with a Zeiss Axiocam digital camera and figures prepared using Adobe Photoshop software. Table 1 provides a summary of the number of immunostains performed and spinal cord levels studied for each specimen. In addition, in one preparation, immunofluorescent double-labelling was carried out. Sections of vertebral column were immunostained for parvalbumin and Er81 as above, cy3-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies (Sigma-Alldrich) were used to visualize parvalbumin and incubation with biotinylated secondary antibody followed by avidin–alexafluor 488 (Molecular Probes) was used to reveal Er81 localization in the same section. Sections were mounted in glycerol and viewed with a Leica laser confocal microscope.

Table 1.

A summary of the immunostains used

| Specimen age (GW) | Immunostains employed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical | Thoracic | Lumbar | Sacral | |

| 7.5 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 |

| 8.5 | PV, NPNF, Er81, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, Er81, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, Er81, GAP43, EphA4 | |

| 9 | PV, GFAP, SYN | PV, GFAP, SYN | PV, GFAP, SYN | PV, GFAP, SYN |

| 9 | NPNF, GAP43, GFAP | NPNF, GAP43, GFAP | ||

| 9 | NPNF, Er81 | NPNF, Er81 | ||

| 10 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EPHA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EPHA4 | |

| 10 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 |

| 11 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | |

| 11 | NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 |

| 11 | PV/Er81 double stain | PV/Er81 double stain | ||

| 12 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | ||

| 12 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | |

| 12 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, EphA4 |

| 12 | NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, SYN | NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, SYN | NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, SYN | |

| 13 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | |

| 13 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, EphA4 |

| 14 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, Er81 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, Er81 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, Er81 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP, Er81 |

| 16 | PV, NPNF, GFAP | PV, NPNF, GFAP | PV, NPNF, GFAP | |

| 17 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, EphA4 |

| 17 | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP | PV, NPNF, GAP43, GFAP |

Results

GAP43, parvalbumin, synaptophysin and GFAP expression

At the earliest ages studied (7.5 GW) GAP43 was strongly expressed in the growing axons of the future ‘white matter’. Expression in the ‘grey matter’ was relatively weak except that axon tracts traversing the dorsal and ventral horns could be seen. GAP43 axons exiting the dorsal columns crossed the dorsal horn and the intermediate zone but stopped short of entering the ventral horn (Fig. 1A). Both the dorsal columns and these axons were also strongly PV-positive (Fig. 1B). In the ventral horn, no PV-positive axons were observed but GAP43-positive axons could be seen in two locations: crossing the grey matter from the lateral funiculi towards the central canal with GAP43-positive neurites clearly visible entering the ventricular zone, and axons entering the ventral floor plate region, apparently arising from a more dorsal location (Fig. 1A,C). Synaptophysin was strongly expressed in the ventral horn only by this stage, particularly around the ventrolateral borders of the motor columns (Fig. 2A). Synaptophysin immunoreactivity steadily increased with age, both in the ventral horn and then in the dorsal horn (Fig. 2D). Punctate staining could be seen in the neuropil around the motoneurone cell bodies at both ages although this became more pronounced at older ages (Fig. 2C,E). By 9 GW GAP43 was generally more widely expressed in the grey matter (data not shown) but PV immunoreactivity was still confined to axons deriving from the dorsal column, which by now innervated the motor columns. PV was also strongly expressed in the cell bodies of a proportion of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cells (Fig. 1D,F). GFAP-positive processes were seen to radiate from the ventricular zone around the central canal towards the margin of the spinal cord. This was particularly evident in the ventral horn, especially in the likely location of the ventral roots. In addition, GFAP expression was strong in the dorsal columns and in tracts of fibres that traversed the dorsal horn, in the same location that PV-positive fibres were found (Fig. 1E). By 12 GW GFAP-positive fibres were less obviously aligned and some multiprocessed astrocytes could be observed, particularly in the ventral white matter (data not shown). This apparent gradual transdifferentiation of astrocytes continued through development.

Fig. 1.

GAP43 immunoreactivity at 7.5 GW in the cervical cord shows that the white matter is packed with growing axons at this age. Some axons from the dorsal funiculus can be observed to have grown as far as the intermediate region of the spinal cord (A, arrow). These axons are also strongly PV immunoreactive (B, arrow). GAP43-positive but PV-negative axons appear to leave the ventrolateral funiculus and grow towards the central canal (A) up to and into the neuroepithelial layer (C) within a specific zone marked by arrows in C just ventral to the boundary between basal and alar plates. Other GAP43-positive axons arising from the dorsal horn enter the ventral commissure (B). By 8.5–9 GW PV-positive axons from the dorsal funiculus have traversed the spinal cord grey matter and begun innervation of the lateral motor columns in the ventral horn (VH, D,F). A proportion of sensory neurone cell bodies in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) are also PV immunoreactive (D). GFAP-immunoreactive glial fibres line up in parallel with these growing sensory axons; in addition, radial glial fibres can be seen stretching from the central canal to the outer edge of the spinal cord, especially in the ventral horn (E). Scale bars = 200 µm (A,B,E,F); 50 µm (C); 250 µm (D).

Fig. 2.

Synaptophysin immunoreactivity at two different stages of development. Early in development (A, cervical enlargement), synaptophysin is only intensely expressed in the ventral horn (VH), particularly in the ventrolateral borders of the motor columns. C shows, at higher power, immunoreactivity in the neuropil around negatively stained motoneurones (m). It is moderately expressed in developing axon tracts but is weak in the dorsal horn (DH) grey matter and ventral commissure and absent from the neuroepithelial proliferative zone around the central canal. (B) Small puncta of immunoreactivity in the ventral commissure that could correspond to small synaptic terminals or growth cones. Later in development (D, lumbar enlargement) immunoreactivity has spread to all parts of the grey matter but is at its most intense around the motoneurones, whose cell bodies appear negatively stained, and in the dorsomedial region of the dorsal horn. (E) Synaptophysin immunoreactivity at higher magnification in the ventral horn. Distinct punctuate staining corresponding to synaptic terminals is seen in the neuropil surrounding motoneurones (m). Scale bars = 200 µm (A); 30 µm (B,C,E).

Between 10 and 14 GW, PV immunoreactivity in axons arising from the dorsal columns reached a peak of intensity. Intensely immunoreactive fascicles of axons could be seen crossing the grey matter towards different motoneuronal pools, where the motoneuronal cell bodies could be seen to be surrounded by immunopositve axons (Fig. 3A). Axons also innervated a region just ventromedial to the central canal at all spinal cord levels. At thoracic and upper lumbar levels, from 10 GW, an increasingly dense innervation of putative Clarke's column neurones (see section below) was observed (Fig. 4C). A sparser innervation by PV axons of the dorsal horn could also be seen at higher magnification. By 17 GW PV immunoreactivity was less intense in the axon fascicles and around the motoneurones although it remained intense in the intermediate grey matter and the dorsal columns themselves (Fig. 3B). By this stage some spinal cord neurones also expressed PV, particularly in the ventromedial spinal cord near the ventral root exit zones (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

PV immunoreactivity increases around the motoneurones up to 14 GW such that the neuropil around the motoneuronal cell bodies becomes filled with immunostained fibres (A). However, beyond this age, PV immunoreactivity becomes less intense around motoneurones, although intense staining remains in the intermediate grey matter (B). Some ventromedial PV-positive neuronal cell bodies are observed by 17 GW (B, arrow). Scale bar = 200 µm.

Fig. 4.

NPNF immunoreactivity can be seen in putative spinocerebellar neurones (A, arrow) as early as 10 GW. By 14 weeks (B), Clarke's column is clearly recognizable as an intensely NPNF-positive region and axons can be seen leaving the nucleus, traversing the grey matter (arrows). Thoracic motoneurones (M) are also NPNF-positive. (C) A montage of an NPNF-immunostained hemicord with a PV-immunostained complementary hemicord from a nearby section. The putative Clarke's column neurones are heavily innervated by PV-positive sensory afferents. Spinocerebellar axons can be seen to enter the lateral funiculus (arrows). Scale bar = 200 µm.

NPNF, EphA4 and Er81 expression

Despite these molecules having diverse functions, they were all expressed by motoneurones at all the different stages of development studied. In addition, NPNF immunoreactivity proved a good marker for Clarke's column neurones. At 7.5 GW there was diffuse NPNF immunoreactivity throughout the spinal cord. However, there was more intense expression in the lateral motor columns and in axons in the ventral roots (Fig. 5A). It was also expressed by axons in the ventral commissure. At this age, EphA4 immunoreactivity was present in motoneurones but also regions of the neuroepithelium and in the ventral commissure (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Montages of hemicords from nearby sections immunostained for NPNF or EphA4 and merged at the midline. (A) NPNF immunoreactivity is absent from the white matter (with the exception of the ventral roots) and ventricular layer at 7.5 GW but generally weak to moderate over the whole grey matter. However, motoneurones (M) are already exhibiting stronger NPNF immunoreactivity by this age, as does the region around the ventral commissure. (B) Thirteen-GW lumbar cord in which NPNF immunoreactivity is confined to motoneurones which are clearly organized into lateral (L), central (C) and medial (M) motor columns. At 17 GW (C) other large neurones in addition to motoneurones also express NPNF in lumbar cord, including cells in the deep dorsal horn and the medial ventral horn. The cell–cell recognition molecule EphA4 is expressed by motoneurones (M) from the earliest age studied (A) but also found in the ventral commissure (VC) and in discrete patches along the ventricular zone, including the ventralmost region and more dorsal regions (arrows). It is expressed by motoneurones in all motor columns (B,C) but perhaps more strongly by some motoneurones in the lateralmost pools (L) compared with ventral and medial groups (asterisks). Expression by other neurones is very weak or non-existent; however, there is strong expression along the midline and in the neuroepithelium around the central canal. Scale bar = 200 µm.

From 7.5 GW up to 14 GW, at least in the cervical and lumbrosacral enlargements, NPNF immunoreactivity became confined to motoneurones that are clearly organized into separate motor columns (Fig. 5B). Primary dendrites and axons were also heavily immunopositive. By 17 GW, motoneurone pools were still clearly distinguishable but other large neurones expressed NPNF, including cells scattered throughout the medial ventral horn and a line of pyramidal neurones in lamina VI of the dorsal horn. Primary dendrites of motoneurones appeared tightly confined within motor columns except where they entered the lateral funiculus (Fig. 5C).

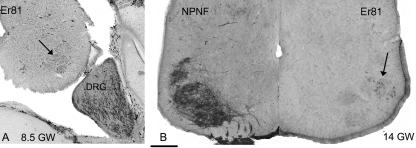

At all ages, motoneurones in every motor column expressed EphA4, although immunostaining appeared stronger in lateral motor columns than in medial columns. EphA4 was also expressed in the ventral commissure, around the central canal and along the midline in the dorsal horn (Fig. 5). Er81 showed a more selective pattern of expression, being confined to selected groups of motoneurones in lateral columns of the cervical and lumbrosacral enlargements at both ages studied (e.g. Fig. 6). Er81 immunoreactivity was weak early in development but increased with age. No Er81-positive motoneurones were observed in thoracic spinal cord sections. Er81 expression was also observed in the dorsal root ganglia (Fig. 6A). A larger proportion of sensory neurones expressed Er81 than did motoneurones. There was also stronger immunostaining of sensory neurones at earlier ages (8.5–11 GW) than in motoneurones. Double immunofluorescent labelling for PV and Er81 at 11 GW showed that the large majority of Er81-positive cells were also PV positive (Fig. 7). There were, however, a small number of cells that were either only PV-positive or only Er81-positive.

Fig. 6.

(A) ETS transcription factor Er81 is expressed strongly in a large proportion of dorsal root ganglion neurones (DRG) at 8.5 GW but expressed weakly in a smaller proportion of motoneurones (arrow) in the lumbar spinal cord. By 14 GW (B) Er81 expression is stronger in motoneurones but only expressed by a proportion of dorsolateral motoneurones. NPNF immunostaining in a complementary hemicord reveals the location of motoneurone columns. Scale bar = 200 µm.

Fig. 7.

Double immunofluorescent labelling for PV (red, mainly found in the cytoplasm) and Er81 (green, mainly in the nucleus) in a lumbar dorsal root ganglion at 11 GW from images obtained by laser scanning confocal microscopy. At low magnification (A) the majority of labelled neurones appear orange with a yellow nucleus, suggesting they are double labelled for both proteins. The higher power image (B), which only scanned through a thickness of 5 µm, demonstrates that there is true double labelling and not overlapping from cells in different plains of focus. An example of double labelling is marked 1. Examples of PV single labelling (2) and Er81 single labelling (3) are also shown, but such cells are relatively rare. Scale bars = 200 µm (A); 50 µm (B).

Thoracic and upper lumbar spinal cord displayed a characteristic pattern of NPNF expression involving a group of large neurones just ventrolateral to the dorsal columns. This pattern of immunoreactivity was apparent from 10 GW and by 14 GW it was clear that this nucleus of cells sent axons to the lateral funiculus and was likely to correspond to Clarke's column of spinocerebellar neurones (Fig. 6).

Discussion

This study used a restricted set of immunohistochemical markers to follow the development of sensorimotor components of the spinal cord. It found that proprioreceptive axons have entered the grey matter, reaching the intermediate grey by 7.5 GW and appear to innervate motoneurones by 8.5–9 GW. At 7.5 GW, synaptophysin immunoreactivity is strongest around the ventrolateral borders of the motoneurone columns, suggesting that the first synapses on motoneurones come predominantly from intraspinal axons projecting over a number of segments or from the earliest arriving descending pathways. Synaptophysin immunoreactivity in the dorsolateral borders of the motor columns coincides with the arrival of PV-positive axons in this region, which progressively innervate the entire motor column region. The onset of this process is 2 weeks earlier than was previously shown by PV immunohistochemistry (Clowry et al. 2000) and suggests a much denser innervation at this age than was demonstrated by Di I tracing of sensory axons from the dorsal root entry zone (Konstantinidou et al. 1995). However, it coincides with the abrupt five-fold increase in the density of axodendritic synapses observed in the ventral horn by electron microscopy between 7 and 9 GW (Okado, 1980). In the rodent, morphological identification of muscle afferents in the ventral horn [embryonic day (E) 17.5 for the lumbar cord] correlates with electrophysiological detection of monosynaptic responses in motoneurones in response to dorsal root stimulation, with monosynaptic stretch reflexes emerging by E19 and continuing to increase in strength for 2–4 days (Kudo & Yamada, 1985, 1987; Ziskind-Conhaim, 1990; Snider et al. 1992). Therefore, this period of development in the rodent [E17 to postnatal day (P) 1] would appear to coincide with 8–14 GW in the human fetus, 14 GW being the peak in PV expression by afferents in the ventral horn.

During this period, limited groups of motoneurones are expressing the ETS transcription factor Er81, suggesting that, as in chicks and mice, expression of Er81 is restricted to subsets of motoneurones innervating particular muscles. Expression was limited to motoneurones in the posterolateral columns of the cervical and lumbar enlargements, Altman & Bayer (2001) suggesting that they innervate wrist/finger or ankle/toe extensors. Selected expression of this factor and other related transcription factors, induced in motoneurones and proprioreceptive neurones by the target muscle, may control expression of cell–cell recognition molecules such as cadherins that will ensure the correct matching of incoming muscle afferents with motoneurones innervating the same muscle (Lin et al. 1998; Price et al. 2002). But in human – as in mouse but unlike the chick – it would appear that Er81 is more widely expressed among DRG cells than among motoneurones. Our study demonstrates that nearly all PV-positive DRG neurones, which correspond to proprioreceptive and some mechanoreceptive neurones (Solbach & Celio, 1991), express Er 81. It is possible that it is the cutaneous mechanoreceptive neurones that innervate skin that fail to express Er81. This suggests that Er81 expression cannot act alone in controlling specificity of muscle spindle afferent–motoneurone connectivity. However, in experiments with ‘knock-out’ mice, Er81 expression by proprioreceptive neurones has been shown to be required for muscle afferents to invade the ventral horn during development (Arber et al. 2000). We also demonstrate a rich innervation of presumptive Clarke's column neurones from an early age by proprioreceptive axons. How matching of axons and targets occurs in this system awaits investigation.

This study provides strong ‘circumstantial’ evidence that GFAP-positive cells, presumably pre-astrocytic cells with properties similar to radial glial cells, provide alignments of fibres that guide the growth of incoming sensory axons to their targets in the ventral horn. The role of radial glia in guiding cell migration away from the ventricular zone is well appreciated, but the axon guidance properties of glial fibres are less well understood. Reactive astrocytes in the mature nervous system produce molecules that are inhibitory to axon growth and regeneration (the glial scar) and during development astrocytes may provide axon-inhibiting boundaries to guide axon pathway formation (Fitch & Silver, 1997). However, human fetal astrocyte precursors do produce axon growth-promoting molecules in vitro (Liesi et al. 2001) and so a role in development in guiding axon growth can be predicted. Radial glial fibres may also guide GAP43-expressing axons growing out of the ventrolateral funiculus into the grey matter of the ventral horn and, in some cases, right up to the ventricular zone. Conceivably, these axons communicate with neural progenitors via release of neurotransmitters or growth factors, as has been suggested for thalamocortical afferents as they grow past the cortical ventricular zone on the way to the subplate (Edgar & Price, 2001). By contrast, these GAP43-positive processes may belong to primitive radial neuroblasts, cells with processes that contact both the ventricular and the pial surfaces but express neuronal markers. Such cells have been described in the developing rat spinal cord (Brittis et al. 1995).

As in the mature nervous system, NPNF immunoreactivity in the developing spinal cord is an excellent marker for large projection neurones such as motoneurones, and spinocerebellar and spinothalamic neurones. Other large neurones of less obvious identity were also observed. NPNF immunoreactivity picked out motoneurones in particular from an early stage, but expression increased markedly after innervation by PV-positive afferents, as did expression by presumptive Clarke's column neurones. This may reflect a trophic effect on target neurones of proprioreceptive afferent innervation. The course of motor axons to the ventral roots and of spinocerebellar axons to the lateral funiculus could be clearly observed. This latter observation suggests that development of this ascending system is well underway despite the relative immaturity of the cerebellum at this age. However, Clarke's column neurones are known to continue to increase in both size and dendritic complexity until around birth in humans and myelination of their axons takes place over a similarly protracted period (Altman & Bayer, 2001). NPNF immunostaining revealed dendritic development in motoneurones. Dendrites could be seen at 13–14 GW, but by 17 GW motoneurones had adopted a multipolar morphology with thick primary dendrites and their cell bodies had become separated from each other, although groups of motoneurones still formed distinct motor columns which largely contained the primary dendrites within them. In the rat the unclustering of motoneurones occurs in the first week postnatally and coincides with the onset of dendritic growth and elimination of electrotonic coupling via gap junctions (Chang et al. 1999; Vinay et al. 2000).

Our studies of EphA4 expression suggest significant differences in expression patterns between human and other species. According to studies in the chick, EphA4 is expressed by those motoneurones of the lateral motor columns that will innervate muscles located on the dorsal surface of the limb and participates in signalling from guidance cues that direct growing axons towards these muscles (Kania & Jessell, 2003). Our study indicates that EphA4 is expressed by all motoneurone groups, although there was some indication that more lateral motor pools expressed it more strongly. However, we have studied a period of development occurring after the outgrowth of motor axons to the limb buds, and EphA4 expression may therefore be playing a different role in motoneuron development at this later period of development.

Expression of EphA4 by corticospinal axons and by glutamatergic ventromedial interneurone axons in mice has been implicated in preventing these axons from crossing the midline in the developing spinal cord. (Coonan et al. 2001; Kullander et al. 2003). The EphA4 ligand ephrin B3 is expressed at the midline and is proposed to interact repulsively with axons expressing EphA4. It is surprising first that we could find no strong evidence for ventral interneurones expressing EphA4 in our preparations, and second that we consistently saw expression of EphA4 along the midline of the spinal cord not previously observed in the rodent spinal cord. Expression patterns for EphA4 and ephrin B3 may differ between human and rodent.

In conclusion, our morphological study of the human fetal spinal cord over the period 7.5–17 GW reveals a period of development similar to the late embryonic/early postnatal period in the rodent (E16.5–P5) (see Table 2). During this time, motoneurones segregate into motor columns. Stretch reflex pathways form and spinocerebellar neurones are innervated; however, descending pathways are only beginning to innervate the spinal cord, and the corticospinal tract, in particular, has not innervated the spinal cord to any significant degree. Mechanisms for specification of cell identity and guidance of axon growth by expression of transcription factors such as Er81, or cell–cell recognition molecules such as EphA4, may be operating in human spinal cord development as they do in other vertebrate species, although not necessarily in exactly the same way.

Table 2.

Timelines for landmarks in spinal cord sensorimotor development in human and rodent

| Human age (gestational weeks) | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11–13 | 14 | 15.5 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat age ( days) | E13 | E14 | E15 | E16 | E17 | E18 | E19 | E20–P0 | P1 | P2 | P3 |

| Human | Birth of motoneurones | Segregation of lat., med., central motor columns Some motoneurones express Er81 | Thickening of proximal dendrites Segregation of somata | ||||||||

| Rat (mouse) | Lumbar motoneurone production | Outgrowth of motor axons Expression of EPHA4 | Segregation of lat., med., central motor columns | Elimination of proximal gap junction coupling between motoneurones | |||||||

| Human | PV positive proprioreceptive afferents enter intermediate zone | PV afferents contact motoneurones Most PV sensory neurones express Er81 | |||||||||

| Five fold increase in synapses in the ventral horn | |||||||||||

| Rat (mouse) | Motor, sensory axons contact muscle. Induction of Er81 expression | PV expression in Proprioreceptive afferents | Sensory axons enter intermediate zone | Sensory axons contact motoneurones. DR stimulation elicits fEPSPs in motoneurones | Fast, heteronymous stretch reflex connections to antagonist muscles detectable | ||||||

| Human | Emergence of independent limb movements | Stimulation of palm/foot elicits finger/toe movement | Effective grasp reflex | ||||||||

| Rat | Stretch reflex appears | Stretch reflex reaches max. amplitude before decreasing | |||||||||

| Human | Identifiable Clarke's column neurones innervated by PV afferents | Clarke's column axons enter lateral funiculus | |||||||||

This table makes a comparison between human and rodent development and attempts to put into register the different rates of development of the species. Similar information for each species is grouped in adjacent, parallel bands. The majority of information on rodent development concerns the rat. Text in italics refers to the mouse, which develops at a slightly faster rate, and therefore the age given may be slightly more mature than the equivalent stage in rat. Information on the development of Clarke's column is very limited in rodent and so it is not included. The information presented was taken from the present study and the following references: Altman & Bayer (2001), Chang et al. (1999), Chen et al. (2003), Eberhart et al. (2002), Kudo & Yamada (1985), Kudo & Yamada (1987), Okado (1980), Snider et al. (1992), Vinay et al. (2000), Zhang et al. (1990) and Ziskind-Conhaim (1990).

Acknowledgments

We thank the consenting women who made this study possible and the research midwives A. Farnsworth and J. Suddes who gained the consent on our behalf. We also thank Dr T. Jessell for kindly providing us with primary antibodies against Er81 and Dr T. Booth for assistance with the confocal microscopy. This study was funded by the Wellcome Trust.

References

- Altman J, Bayer SA. Development of the Human Spinal Cord: an Interpretation Based on Experimental Studies in Animals. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Arber S, Ladle DR, Lin JH, Frank E, Jessell TM. ETS gene Er81 controls formation of functional connections between group 1a sensory afferents and motor neurons. Cell. 2000;101:485–498. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80859-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz LI, Routtenberg A. GAP43; an intrinsic determinant of neuronal development and plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:84–91. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi LM, Gale NW. Distribution of Eph-related molecules in the developing and mature cochlea. Hearing Res. 1998;117:161–172. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittis PA, Meiri K, Dent E, Silver J. The earliest patterns of neuronal differentiation and migration in the mammalian central nervous system. Exp Neurol. 1995;134:1–12. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1995.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanas-Sacre G, Rogister B, Moonen G, Leprince P. Radial glia phenotype: origin, regulation and transdifferentiation. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:357–363. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000815)61:4<357::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Q, Gonzalez M, Pinter MJ, Balice-Gordon RJ. Gap junctional coupling and patterns of connexin expression amongst neonatal rat lumbar spinal motor neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10813–10828. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-24-10813.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H-H, Hippenmayer S, Arber S, Frank E. Development of the monosynaptic stretch reflex circuit. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:96–102. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowry GJ, Fallah Z, Arnott GA. Developmental expression of parvalbumin in rat lower cervical spinal cord neurones and the effect of early lesions to the motor cortex. Dev Brain Res. 1997;102:197–208. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)00098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowry GJ, Arnott GA, Clement-Jones M, Fallah Z, Gould S, Wright C. Changing pattern of expression of parvalbumin during human fetal spinal cord development. J Comp Neurol. 2000;423:727–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coonan JR, Greferath U, Messenger J, et al. Development and reorganisation of corticospinal projections in EphA4 deficient mice. J Comp Neurol. 2001;436:248–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries JIP, Visser GHA, Prechtl HFR. The emergence of fetal behaviour. I. Qualitative aspects. Early Hum Dev. 1982;7:301–322. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(82)90033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart J, Swartz ME, Koblar SA, Pasquale EB, Krull CE. EphA4 constitutes a population-specific guidance cue for motor neurons. Dev Biol. 2002;247:89–101. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar JM, Price DJ. radial migration in the cerebral cortex is enhanced by signals from the thalamus. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1745–1754. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch MT, Silver J. Glial cell extracellular matrix: boundaries for axon growth in development and regeneration. Cell Tissue Res. 1997;290:379–384. doi: 10.1007/s004410050944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hern WM. Correlation of fetal age and measurements between 10 and 26 weeks of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;63:26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kania A, Jessell TM. Topographic motor projections in the limb by LIM homeodomain protein regulation of Ephrin-A: EphA interactions. Neuron. 2003;38:581–596. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidou AD, Silos-Santiago I, Flaris N, Snider WD. Development of the primary afferent projection in the human spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1995;354:1–12. doi: 10.1002/cne.903540102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo N, Yamada T. Development of the monosynaptic stretch reflex in the rat: an in vitro study. J Physiol. 1985;369:127–144. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo N, Yamada T. Morphological and physiological studies of development of the monosynaptic stretch reflex pathway in the rat lumbar spinal cord. J Physiol. 1987;389:441–459. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullander K, Butt SJB, Lebret JM, et al. Role of EphA4 and Ephrin B3 in local neuronal circuits that control walking. Science. 2003;299:1889–1982. doi: 10.1126/science.1079641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc NP, Beesley W, Brown I, et al. Synaptophysin expression during synaptogenesis in the rat cerebellar cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1989;280:197–212. doi: 10.1002/cne.902800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MK, Cleveland DW. Neurofilament function and dysfunction: involvement in axonal growth and neuronal disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:34–40. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt P, Rakic P. Immunoperoxidase localisation of glial fibrillary acidic protein in radial glial cells and astrocytes in the developing rhesus monkey brain. J Comp Neurol. 1980;193:815–840. doi: 10.1002/cne.901930316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesi P, Fried G, Stewart RR. Neurons and glial cells of the embryonic human brain and spinal cord express multiple and distinct isoforms of laminin. J Neurosci Res. 2001;64:144–167. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JH, Saito T, Anderson DJ, Lance-Jones C, Jessell TM, Arber S. Functionally related motor neuron pool and muscle sensory afferent subtypes defined by co-ordinate ETS gene expression. Cell. 1998;95:393–407. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okado N. Development of the human spinal cord with reference to synapse formation in the motor nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1980;191:495–513. doi: 10.1002/cne.901910311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RS, De Marco Garcia NV, Ranscht B, Jessell TM. Regulation of motor neuron pool sorting by differential expression of type II cadherins. Cell. 2002;109:205–216. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00695-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider WD, Zhang L, Yusoof S, Gorukanti N, Tsering C. Interactions between dorsal root axons and their target motor neurons in the developing mammalian spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3494–3508. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-09-03494.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solbach S, Celio MR. Ontogeny of the calcium binding protein parvalbumin in the rat nervous system. Anat Embryol. 1991;184:103–124. doi: 10.1007/BF00942742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang YM, Chiong F, Kuznetsov D, Kasarkis E, Guela C. Motor neurons are rich in non-phosphorylated neurofilaments: cross-species comparison and alterations in ALS. Brain Res. 2000;861:45–58. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)01954-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinay L, Brocard F, Pflieger J-F, Simeoni-Alias J, Clarac F. Perinatal development of lumbar motoneurons and their inputs in rats. Brain Res Bull. 2000;53:635–647. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00397-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenmann B, Franke WW. Identification and localization of synaptophysin, an integral membrane glycoprotein of Mr 38,000 characteristic of presynaptic vesicles. Cell. 1985;41:1017–1026. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J-H, Morita Y, Hironaka T, Emson PC, Tohyama M. Ontological study of calbindin-D28k-like immunoreactivities and parvalbumin-like immunoreactivities in rat spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia. J Comp Neurol. 1990;302:715–728. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziskind-Conhaim L. NMDA receptors mediate poly- and monosynaptic potentials to motoneurones of rat embryos. J Neurosci. 1990;10:125–135. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-01-00125.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]