Abstract

The aims of this study were to examine the possible alterations occurring in the effects of kinins on isolated aortae of inbred control (CHF 148) and cardiomyopathic (CHF 146) hamsters of 150–175 and 350–375 days of age.

Bradykinin (BK) and desArg9BK contracted isolated aortae (with or without endothelium) of hamsters of both strains and ages. After tissue equilibration (90 min), responses elicited by both kinin agonists were stable over the time of experiments. The patterns of isometric contractions of BK and desArg9BK were however found to be different; desArg9BK had a slower onset and a longer duration of action than BK.

Potencies (pEC50 values) of BK in all groups of hamsters were significantly increased by preincubating the tissues with captopril (10−5 M).

No differences in the pEC50 values and the Emax values for BK or desArg9BK were seen between isolated vessels from inbred control and cardiomyopathic hamsters.

The myotropic effect of BK was inhibited by the selective non peptide antagonist, FR 173657 (pIC50 7.25±0.12 at the bradykinin B2 receptor subtype (B2 receptor)). Those of desArg9BK, at the bradykinin B1 receptor subtype (B1 receptor) were abolished by either R 715 (pIC50 of 7.55±0.05; αE=0), Lys[Leu8]desArg9BK (pIC50 of 7.21±0.01; αE=0.22) or [Leu8]desArg9BK (pIC50 of 7.25±0.02; αE=0.18).

FR 173657 had no agonistic activity, exerted a non competitive type of antagonism and was poorly reversible (lasting more than 5 h) from B2 receptor. In vivo, FR 173657 (given per os at 1 and 5 mg kg−1, 1 h before the experiment) antagonized the acute hypotensive effect of BK in anaesthetized hamsters.

It is concluded that aging and/or the presence of a congenital cardiovascular disorder in hamsters are not associated with changes in the in vitro aortic responses to either BK or desArg9BK.

Keywords: Kinins, B1 and B2 receptors, hamster, tissues, age, cardiomyopathy

Introduction

Syrian golden hamsters of the cardiomyopathic strain have a disease that originates from a genetically-transmitted metabolic anomaly which induces degenerative lesions in all striated muscles with particular intensity in the heart (Chemla et al., 1991). The development of the pathology is characterized by the occurrence of focal myocardial degeneration and it can be divided into four temporal phases: prenecrotic (25–30 days), necrotic (70–75 days), hypertrophic (150–175 days) with progressing dilatation (225–250 days), and severe heart failure (350–375 days) (Hunter et al., 1984). The clinical course and pathological aspects of the hamster's chronic cardiac condition resembles hypertrophic cardiomyopathy observed in the clinic. As in humans, the resulting depression of cardiac function is associated with a significant decrease in life expectancy.

The cardiomyopathic hamsters display an activated renin-angiotensin system characterized by higher plasma and ventricular angiotensin II concentrations, increased angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) and chymase activity, as well as upregulation of cardiac angiotensin 1 receptor subtypes (AT1 receptors) (Lambert et al., 1995a,1995b). We have recently reported that chronic blockade of AT1 receptors with a specific antagonist (losartan, 100 mg−1 kg−1 day−1) is associated with a significant reduction in the survival of cardiomyopathic animals whereas chronic ACE inhibition (quinapril, 100 mg kg−1 day−1) significantly improved their life expectancy (↓73% risk of cardiac death) (Bastien et al., 1999). In this survival study, ACE inhibition caused a significant decrease in cardiac hypertrophy whereas AT1 antagonism did not prevent and even accentuated its development. While there is no definitive explanation for interpreting our results, they do suggest, among other hypotheses, that cardiac AT1 receptors are not directly involved or at least do not play a critical role in the progression of cardiac remodelling and/or hypertrophy.

It is well established that ACE inhibition not only attenuates the formation of angiotensin II but also inhibits the degradation of kinins. There is actually growing evidence that the beneficial effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) are mediated by the attenuation or prevention of the systemic and local actions of angiotensin II and also by the potentiation of the positive cardiovascular and metabolic effects of kinins (Linz et al., 1997). It is therefore highly plausible that, in the cardiomyopathic hamster, the cardioprotective effect of ACE inhibition that we observed was related to the accumulation of endogenous kinins acting either at the B1 or B2 receptor subtype or both. The B2 receptor is known to be constituvely expressed in many cell types while the B1 receptor is mainly inducible and is formed de novo by stimuli which activate the cytokine system (Marceau, 1995). Interestingly, it has been found that in individual suffering of clinical heart failure, the plasmatic level of these inflammatory cytokines is increased (Lommi et al., 1997).

To the best of our knowledge, the kinin system in the cardiovascular domain has never been studied in hamsters. The first aim of this study was therefore to investigate the functional vascular B1/B2 receptor expression in 150–175- and 350–375-day-old inbred control and cardiomyopathic hamsters, using isolated aortic rings, as well as to identify suitable pharmacological tools (B1 and B2 specific and selective kinin receptor agonists and antagonists) for characterizing kinin responses in vitro and in vivo.

The second aim was to identify a potent selective B2 kinin receptor antagonist that can be administered orally. The antagonistic effects of FR 173657, a non peptide B2 antagonist, against bradykinin-induced decrease in blood pressure, were thus evaluated in anaesthetized hamsters following its oral administration.

Methods

In vitro pharmacological assays

Isolated tissues were taken from male Syrian inbred control (CHF 148) and cardiomyopathic (CHF 146) hamsters of 150–175 and 350–375-day-old. The animals purchased from the Canadian Hybrid Farms (Halls Harbour, Nova Scotia, Canada) were sacrificed by exsanguination after being narcotized by a short exposure to a 100% CO2 atmosphere. Isolated aortae were selected among other vessels (e.g. portal, cava and jugular veins, carotid and pulmonary arteries) on the basis of their high sensitivities to both B1 and B2 kinin receptor agonists, desArg9-Bradykinin (and LysdesArg9Bradykinin) and Bradykinin (BK). All procedures for animal experimentation conformed to the guidelines of the Canadian Council for Animal Care and were monitored by an institutional animal care committee.

Circular rings of aorta (4 mm) (n=75) were prepared and suspended in 10 ml siliconized glass organ baths containing Krebs solution (37°C) oxygenated with a mixture of 95% O2- 5% CO2. The composition (mM) of the Krebs solution was as follows; NaCl 118.1, KCl 4.7, CaCl26H2O 2.5, KH2PO4 1.2, MgSO47H2O 1.18, NaHCO3 25.0 and D-glucose 5.5. Tissues were stretched with a tension of 0.5 g weight and allowed to equilibrate for 60–90 min. During this period, the baseline tension was adjusted every 20 min, if necessary. Changes in tension produced by various agents were measured using isometric transducers (FT 03C, Grass Instrument Co., Quincy, MA, U.S.A.) and displayed on a polygraph (model 7D, Grass Instrument Company). Pilot experiments (n=7) have shown that BK (up to 1 μM) and desArg9BK (up to 1 μM) evoke no relaxation of endothelium intact precontracted (phenylephrine; 50 nM) tissues in contrast to acetylcholine (100 nM) (data not shown). After the equilibration period, the experiments were initiated by applying a submaximal concentration of BK (10 nM) or desArg9BK (100 nM) to verify the stability of the tissue contraction. Cumulative concentration-response curves were then constructed for BK and desArg9BK (or LysdesArg9BK) by adding increasing concentrations of the agonists (1–10,000 nM). Potencies of agonists are expressed in terms of pEC50 which represents the−logarithm of the molar concentration of the agonist that produces 50% of the maximum effect (Emax).

In all groups of hamsters, the in vitro intramural inactivation of BK was evaluated by comparing cumulative concentration-response curves to BK obtained in the absence or in presence of a carboxypeptidase M inhibitor (mergetpa, 10 μM) or an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI, captopril, 10 μM). A delay of 60–90 min was allowed between the first (control) and second (with the inhibitor) cumulative concentration-response curves of BK. Addition of the inhibitors to the organ baths was made 30 min before the recording of the second concentration-response curve. Control assay in concurrent tissues without the inhibitors demonstrated that no changes in BK pEC50 or Emax values are observed between the first and second concentration-response curves. In another series of experiments performed on tissues from hamsters (150–175 day-old) (n=4), the effect of cycloheximide (a protein synthesis inhibitor given at 70 μM; given 60 min before) (Regoli & Barabé, 1980) on the concentration-response curves of desArg9BK and BK, was investigated.

Potencies of B2 kinin receptor antagonists (FR 173657, Asano et al., 1997; HOE 140, Hock et al., 1991) and B1 kinin receptor antagonists ([Leu8]desArg9BK and Lys[Leu8]desArg9BK, Regoli et al., 1977; AcLys[DβNal7, Ile8]desArg9BK (R 715), Gobeil et al., 1996) were estimated in the two groups of hamsters. Potencies of antagonists are expressed as pIC50 representing the −logarithm of the molar concentration of the antagonist that reduces a response to 50% of its former value (Jenkinson et al., 1995). The peptide antagonists were applied 10 min before the B1 or B2 kinin agonist whereas the non peptide antagonist FR 173657 was incubated for 60 min to reach equilibrium (longer time exposition (up to 120 min) was not correlated with an increased inhibition). All antagonists were initially added to the organ baths at a concentration of 10 μg ml−1 to evaluate their potential agonistic activities (αE) compared to those of BK and desArg9BK.

Finally, in order to establish the type of antagonism exerted on B2 kinin receptors by FR 173657, aortae of inbred control hamsters of 150–175-day-old (n=7) were prepared. A minimum of three concentrations of FR 173657 (10–100–1000 nM) were added to each preparation to built a Schild plot.

In vivo haemodynamic experiments; effect of FR 173657

Based on in vivo protocols described for the guinea-pig, the rabbit and the rat (Gobeil et al., 1996; 1999), control hamsters of 150–175-day-old (n=11) were anaesthetized with a mixture of ketamine/xylazine (90 and 5 mg kg−1, i.m.) and supplemented when needed to maintain anaesthesia. A polyethylene catheter (PE 50) filled with heparin sodium (1000 u ml−1) was inserted into the right carotid artery to monitor arterial blood pressure with a transducer connected to a blood pressure analyzer (Harvard apparatus). A second cannula was inserted into the left carotid artery for bolus injection (10–20 s) of the agonists. Following a stabilization period of 45–60 min, increasing doses of BK or desArg9BK (10–5000 ng kg−1 in 200 μl of isotonic saline with 0.1% BSA) were injected at 5–10 min intervals. After each injection, the catheter was flushed with 150 μl (10–20 s) of isotonic saline. In nine other control hamsters, FR 173657 (0.5, 1 and 5 mg kg−1; dissolved in 150 μl of 0.1N HCl) was administered orally by gavage at the end of the surgical procedure. Sixty minutes following gavage, increasing doses of the agonists were then injected as described above. The 1 mg kg−1 dose of FR 173657 has already been used by Asano et al. (1997) to inhibit BK induced bronchoconstriction in anaesthetized guinea-pigs. The effect of the agonists was determined as the maximal induced decrease in diastolic pressure (mmHg). The dose of BK needed to reach 50% (ED50) of the maximal effect (Emax; arbitrarily fixed at 40–50 mmHg; 1 mmHg=133.3 Pa) was calculated from the corresponding concentration-response curve by least-square regression analysis (Tallarida & Murray, 1987).

Drugs

All peptides were prepared by solid-phase synthesis and purified by high pressure liquid chromatography as described by Drapeau & Regoli (1988). FR 173657 ((E) -3- (6-acetamido-3-pyridyl) -N- [N-2-4-dichloro -3- [(2-methyl-8-quinolinyl) oxymethyl]phenyl] -N- methylamino-carbonyl-methyl] acrylamide) was kindly supplied by Dr N. Inamura (Fujisawa Co., Osaka, Japan) and HOE 140 (DArg[Hyp3, Thi5, DTic7, Oic8]BK) by Dr B.A. Schölkens (Hoechst AG, Frankfurt, Germany). Concentrated solutions (1 mg ml−1) of peptides were made in water and kept at −20°C. FR 173657 (1 mg ml−1) was dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) to a final concentration not exceeding 1% in the organ baths. Captopril ([2S]-1-[3-mercapto-2-methyl-propionyl]-L-proline) was purchased from Squibb Canada and dissolved in bidistilled water. Mergetpa (DL-2-mercaptomethyl-3-guanidinoethyl propanoic acid) and cycloheximide were obtained from Calbiochem-Boehringer (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.) and dissolved in 10% DMSO and water, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean±s.e.mean. Differences between groups were analysed using Student's t-test for unpaired samples followed by MannWhitney t-tests. The critical level of significance was set at P<0.05. Schild plot linear regression slope was calculated from the experimental points using the Tallarida & Murray (1987) computer program.

Results

In vitro pharmacological assays

Figure 1 illustrates typical contractions induced by BK and desArg9BK on isolated endothelium-denuded aortic rings from inbred control and cardiomyopathic hamsters of 150–175-day-old. In all groups of animals, the response induced by desArg9BK had a slower onset and a longer duration of action than that of BK. Responses induced by both kinin agonists were shown to be immediate and stable after an equilibration period of 60–90 min and were not affected by a tissue-pretreatment with cycloheximide (70 μM), an inhibitor of protein synthesis (n=4, data not shown), applied 60 min before.

Figure 1.

Typical contraction tracings obtained following the addition of B2 and B1 kinin receptor agonists, BK (10 nM) and desArg9BK (100 nM), to isolated endothelium-denuded aortic rings of inbred control (upper) and cardiomyopathic (bottom) hamsters of 150–175-day-old. Abscissa: time (min). Ordinate: isometric contraction in gram weight (g weight). W: washing out of agents.

Figure 2 and Table 1 show that there are no significant differences in cumulative concentration-response curves, pEC50 and Emax obtained following the addition of increasing doses of BK and desArg9BK to isolated endothelium-denuded aortic rings of inbred control and cardiomyopathic hamsters of 150–175- and 350–375-day-old. Maximal effects (Bmax) elicited by BK were always higher, by approximately 3 fold (P<0.001), than those induced by desArg9BK. DesArg9BK was used as B1 receptor agonist since it was shown that this compound is as active (pEC50 7.32±0.05, n=5) as LysdesArg9BK (pEC50 7.29±0.11, n=4) (data not shown) in tissues from inbred control hamsters.

Figure 2.

Concentration-response curves of BK and desArg9BK obtained on isolated endothelium-denuded aortic rings of inbred control and cardiomyopathic hamsters of 150–175- and 350–375-day-old, in the presence of captopril (10 μM). Values are mean±s.e.mean, n=8–15 experiments.

Table 1.

In vitro potencies of B1 and B2 kinin receptor agonists (desArg9BK and BK) determined using isolated endotheliumdenuded aortic rings in presence or not of captopril (ACEI, 10 μM)

Preliminary experiments indicated that the carboxypeptidase M inhibitor, mergetpa (10 μM), does not exert potentiating or inhibitory effect on the contractile response induced by BK whereas the ACEI, captopril (10 μM), displaces to the left the concentration-response curves of the peptide. The left-shifts resulted in significant increases of apparent affinities (pEC50) of BK in all tissues tested (Table 1).

FR 173657 displayed very high in vitro antagonistic potencies (pIC50 ranging from 7.3 to 7.6) and no residual agonistic activities (αE=0) on the B2 kinin receptor (Table 2). As a control reference, Figure 3 clearly shows that the contractile response elicited by BK (47 nM) in aortic rings of hamsters of 150–175-days-old is constant for at least 5 h indicating no desensitization of the receptor with frequent agonist stimulation. In this context, Figure 3 equally shows that the antagonistic effect of FR 173657 (42 nM) against that of BK (47 nM) persists for more than 5 h, despite frequent washings. The antagonism produced by FR 173657 (16–1600 nM) is non competitive since the right-shifts of the concentration-response curves were accompanied by significant decreases of the maximal effect induced by BK (Figure 4A). The Schild regression analysis confirmed this observation showing a slope significantly different from unity (m=0.52±0.13; n=4) (Figure 4B). On the other hand, the antagonistic effect of HOE 140 on B2 kinin receptor was rapidly reversible, lasting for less than 15 min, with a corresponding pIC50 of 7.92±0.19 (n=6) and no agonistic residual activity (αE=0, n=2) (data not shown).

Table 2.

In vitro potencies of non-peptide B2 kinin receptor antagonists, FR 173657 (42 nM), determined using isolated endothelium-denuded aortic rings in the presence of captopril (10 μM)

Figure 3.

Duration (h) of the in vitro antagonistic effect of the non-peptide B2 kinin receptor antagonist FR 173657 (42 nM), on the contractile response induced by BK (47 nM) on isolated endothelium-denuded aortic rings of inbred control hamsters of 150–175-day-old. Abscissa: Time (0–5 h). Ordinate: Isometric tension in gram weight (g weight). W: washing out of agents.

Figure 4.

(A) Cumulative concentration-response curves obtained with BK on isolated endothelium-denuded aortic rings of inbred control hamsters of 150–175-day-old in the absence or in presence of increasing concentrations of FR 173657 (16–1600 nM). Organ baths contained captopril (10 μM). (B) Schild plot of the antagonistic effect of FR 173657 against the agonistic effect of BK Abscissa: −log of the molar (M) concentration of FR 173657. Ordinate: −log of the concentration-ratio-1 (CR-1) of BK. Values are mean±s.e.mean, n=4.

Finally, it is worthwhile to mention that the contractile effect of desArg9BK elicited on aortic rings of inbred control hamsters of 150–175-day-old, was inhibited by two categories of B1 receptor antagonists, the [Leu8]desArg9BK (pIC50 of 7.25±0.02 and αE=0.18, n=3) and Lys[Leu8]desArg9BK (pIC50 of 7.21±0.01 and αE=0.22, n=3) and, the AcLys[DβNal7, Ile8]desArg9BK (pIC50 of 7.55±0.05 and αE=0, n=3) (data not shown). Selectivity of action of these latter B1 receptor antagonists (tested at 10 μg ml−1) was also demonstrated by their inability to block the response elicited by BK (not shown, n=3). Similar results were obtained with FR 173657 or HOE 140 when tested against desArg9BK (not shown, n=3).

In vivo haemodynamic experiments; effect of FR 173657

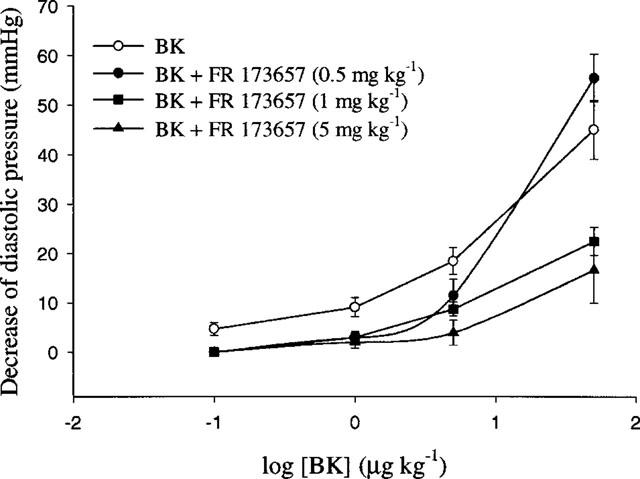

The injection into the right carotid artery of exogenous BK (10–5000 ng kg−1) induced a dose-dependent decrease of blood pressure in anaesthetized control hamsters (n=11, Figure 5) whereas the administration of desArg9BK (10–5000 ng kg−1) elicited no effect (n=3, data not shown). In vivo assays performed in cardiomyopathic anaesthetized hamsters (of either age) with BK and desArg9BK gave similar results; BK was found to produce hypotensive effects comparable to those of the control animals while desArg9BK (up to 5000 ng kg−1) was inactive (n=3, data not shown). The inhibitory effect of FR 173657 (0.5, 1 and 5 mg kg−1) on BK-induced acute hypotensive response was evaluated 1 h after its oral administration by gavage (n=14). While there was no effect elicited by the low-dose (n=4 for 0.5 mg kg−1), a significant rightward displacement of the cumulative dose-response curves to BK was observed with the high-doses (n=6 for 1 mg kg−1 and n=4 for 5 mg kg−1) of FR 173657. Again, these results suggest that the antagonistic effect of FR 173657 on kinin B2 receptor is non competitive since the maximal effect induced by BK was reduced.

Figure 5.

Cumulative dose-response curves to BK obtained in anaesthetized control hamsters of 150–175-day-old treated or not with FR 173657 (0.5, 1 and 5 mg kg−1) administered orally by gavage at the end of the surgical procedure. Increasing doses of BK were injected 60 min following gavage. Values are mean±s.e.mean, n=4–11. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated the presence of functional kinin B1 and B2 receptors in isolated aortae of control hamsters and of hamsters suffering from a congenital cardiomyopathic disorder. We have shown that aortae of control and cardiomyopathic hamsters respond to kinins in a similar manner, both in terms of sensitivities and potencies (pEC50 values) as well as maximal effects (Emax values), despite genetic alterations and aging. It appears therefore that the development and occurrence of heart failure in cardiomyopathic hamsters are not accompanied by either an upregulation of B2 (as well as B1) receptors nor by alterations in the cellular transduction mechanisms of the two kinin receptor types at least, in a conductance vessel such as the aorta. Pharmacological parameters on kinin receptor functionality as well as the density and distribution of kinin receptors within the heart of these control and cardiomyopathic animals are currently under investigation.

Interestingly, we found that smooth muscle preparations of hamster aortae constitutively express both kinin B1 and B2 receptors, as demonstrated by the immediate and stable tissue-responsiveness to desArg9BK (see Figure 1) and also by the inability of cycloheximide (given at 70 μM according to Regoli & Barabé, 1980) to affect the concentration-response curves of either desArg9BK or BK (n=4, data not shown). The presence of constitutive B1 receptors has also been observed in the dog and the cat. Thus, in the dog, the vasorelaxation induced by desArg9BK on isolated renal artery precontracted with noradrenaline, is immediate (after a 60 min equilibration period) and stable over time (for at least 7 h) (Rhaleb et al., 1989). Again in the dog, several in vivo responses elicited by exogenously administered desArg9BK (e.g. hypotension, natriuresis, renal vasodilatation) are observed (Lortie et al., 1992; see also Marceau, 1995) already after the first injection of desArg9BK. By opposition, in rabbits, mice, pig, cows and in man, B1 receptors are induced de novo (Marceau et al., 1998). As pointed out by Marceau et al. (1998), differences in the promoter region of the B1 receptor coding gene between species may account for the constitutive versus the inducible expression observed for this receptor. This hypothesis however, still remain to be proved.

In this study, we have also shown that the pattern of myotropic responses mediated by the kinin B2 receptor differ from those of the B1 receptor (Figure 1). Such difference in the in vitro contractile responses evoked by B2 and B1 receptors has already been reported by others (e.g. in murine stomachal tissues: Nsa Allogho et al., 1995; 1998) and has been attributed to distinct pattern of intracellular Ca2+ mobilization (Bascands et al., 1993; Smith et al., 1995; Mathis et al., 1996). The differential message produced by desArg9BK and BK is in fact characterized by a relatively slow onset and a sustained increase in cytosolic free Ca2+ signal elicited by the B1 agonist whereas that produced by the B2 receptor agonist is transient.

Pharmacological spectra of hamster B1 and B2 kinin receptors resemble those previously described for the mouse (Nsa Allogho et al., 1995; 1997) and the rat (Regoli et al., 1994b; Meini et al., 1996); as a matter of fact, these species are thought to be closely-related phylogenetically. Thus, potencies of desArg9BK and LysdesArg9BK, are similar (pEC50 values ≈7.30) and are compatible to those reported for other contractile assays in the mouse (the stomach; Nsa Allogho et al., 1995) and the rat (the ileum; Meini et al., 1996). Classical B1 receptor selective antagonists, Lys[Leu8]desArg9BK and [Leu8]desArg9BK, exhibited comparable potencies (pIC50 ≈7.20) and some residual agonistic activities when applied at high concentrations (αE=0.20), a finding already reported in the mouse (Nsa Allogho et al., 1995). Another selective B1 antagonist, R 715, demonstrated higher potency (by 2 fold) and was devoid of agonistic effect (αE=0). Hence, this compound was selected for studying B1 receptor in vitro in hamsters as we did in mice (Nsa Allogho et al., 1995).

BK elicited contractile responses in the two strains of hamsters through activation of B2 receptors. These effects were potentiated, in a concentration-dependent manner (data not shown), by the addition of captopril (see Table 1). These results suggest that ACE may be present in the smooth muscle membrane of hamster aortae and shows a similar affinity for BK as the B2 receptor, all over a large range of concentrations. They also point to the need of using peptidase inhibitors to avoid metabolic interferences when comparing the potencies of agonists and antagonists in the process of receptor characterization and classification.

We have shown that the responses elicited by BK can be inhibited by preincubating the tissues with selective B2 receptor antagonists as HOE 140 and FR 173657 (Regoli et al., 1998). Despite their similar inhibitory potencies (pIC50 value ranging from 7.3 to 7.9), these compounds interact with the hamster B2 receptor in a different way. In fact, the peptide HOE 140 shows a rapid onset and a short duration of action while the non-peptide FR 173657 has a prolonged effect (for several hours). This may be explained by the fact that HOE 140 associates and dissociates more rapidly to and from the B2 receptor than FR 173657. Moreover, the undisputed longer antagonistic effect of FR 173657 (>5 h; see Figure 3) compared to that of HOE 140 (⩽15 min), should thus be attributed to slower rate of dissociation from the B2 receptor. When analysed with the Schild plot regression, results obtained with FR 173657 indicate that this compound exerts a non-competitive type of antagonism (see Figure 4) which has also been observed in the mouse (Nsa Allogho et al., 1997) and the guinea-pig (Rizzi et al., 1997) while HOE 140 is competitive. Differences in the pharmacodynamic properties of receptor antagonists such as those observed with HOE 140 (competitive) and FR 173657 (non competitive) may indicate the existence of B2 receptor subtypes, as already demonstrated for the NK-1 receptor (human versus rat NK-1) with CP 96345 and RP 67580 (Regoli et al., 1994a). Such differences may also influence potencies and duration of action in vivo, as pointed out by Gobeil et al. (1999), for kinin receptor antagonists.

The oral bioavailability of FR 173657, first described by Asano et al. (1997) in rats has been confirmed in the present study in anaesthetized hamsters. Non-peptide antagonists have advantages over peptide-based antagonists mainly because of their better oral absorption and metabolic stability. FR 173657, administered per os, inhibited, in a dose-dependent manner, the acute hypotensive effect of exogenously administered BK (see Figure 5). One can therefore reasonably expect that, following the in vivo administration of the high-dose (1 mg kg−1) used herein, FR 173657 will antagonize the physiological effects produced by endogenous kinins whose plasma concentrations are known to be very low. The high potency and selectivity of FR 173657 as well as its long duration of action when given orally strongly support its candidature for chronic in vivo studies on the role of endogenous kinins in all kind of physiological functions; their use can also be envisaged to ascertain the beneficial effects of ACE inhibitors (e.g. reduced cardiac hypertrophy and increased survival) in cardiomyopathic hamsters and their relation to the accumulation of endogenous kinins within the heart (Bastien et al., 1999). This hypothesis is at present under investigation in our laboratory, using this antagonist.

In conclusion, we have defined the pharmacological characteristics of kinin receptors expressed in aortic preparations of hamsters and outlined similarities or differences between these receptors and their homologues that are found in other species. We have also demonstrated that aging and the presence of a cardiomyopathy do not modify the vasocontractile responses induced by BK and desArg9BK in the aorta. We also have identified suitable pharmacological tools, such as R 715 and FR 173657 to be used in vivo in hamsters to further investigate the role that kinins and their receptors may play in the genesis and maintenance of congenital cardiomyopathy and on the beneficial effects of ACE inhibitors (Bastien et al., 1999) in cardioprotection and survival of cardiomyopathic hamsters.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr W. Neugebauer for contributing the synthesis of some peptides and Mr Martin Boussougou and Mrs Francine Legault for their excellent technical assistance. F. Gobeil Jr. holds a studentship from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (HSFC). This work was supported by grants from the HSFC and the Medical Research Council of Canada.

Abbreviations

- ACE

angiotensin converting enzyme

- ACEI

angiotensin converting enzyme

- AT1

angiotensin 1 receptor subtype

- BK

bradykinin

- B1 receptor

bradykinin B1 receptor subtype

- B2 receptor

bradykinin B2 receptor subtype

References

- ASANO M., INAMURA N., HATORI C., SAWAI H., FUJIWARA T., KATAYAMA A., KAYAKIRI H., SATOH S., ABE Y., INOUE T., SAWADA Y., NAKAHARA K., OKU T., OKUHARA M. The identification of an orally active non peptide bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist, FR 173657. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:617–624. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BASCANDS J.L., PECHER C., ROUAUD S., EMOND C., LEUNG TACK J., BASTIE M.J., BURCH R., REGOLI D., GIROLAMI J.P. Evidence for existence of two distinct bradykinin receptors on rat mesangial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:F548–F556. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.3.F548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BASTIEN N.R., JUNEAU A.V., OUELLETTE J., LAMBERT C. Chronic AT1 receptor blockade and ACE inhibition in (CHF 146) cardiomyopathic hamsters: Effects on cardiac hypertrophy and survival. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999;43:77–85. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEMLA D., SCALBERT E., DESCHÉ P., LECARPENTIER Y. La cardiomyopathie du hamster Syrien. Arch. Mal. Coeur. 1991;84:85–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRAPEAU G., REGOLI D. Synthesis of bradykinin analogues. Methods Enzymol. 1988;163:263–272. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)63025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOBEIL F., JR, MONTAGNE M., INAMURA N., REGOLI D. Characterization of non peptide bradykinin B2 receptor agonist (FR 190997) and antagonist (FR 173657) Immunopharmacology. 1999;43:179–185. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOBEIL F., NEUGEBAUER W., FILTEAU C., JUKIC D., NSA ALLOGHO S., PHENG L.H., NGUYEN-LE X.K., BLOUIN D., REGOLI D. Structure-activity studies of B1 receptor-related peptides. Antagonists. Hypertension. 1996;28:833–839. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOCK F.J., WIRTH K., ALBUS U., LINZ W., GERHARDS H.J., WIEMER G., HENKE S.T., BREIPOHL G., KÖNIG W., KNOLLE J., SCHÖLKENS B.A. Hoe 140, a new potent and long acting bradykinin-antagonist: in vitro studies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;102:769–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNTER E.G., HUGUES V., WHITE J. Cardiomyopathic hamsters, CHF 146 and CHF 147: a preliminary study. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1984;62:1423–1428. doi: 10.1139/y84-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JENKINSON D.H., BARNARD E.A., HOYER D., HUMPHREY P.P.A., LEFF P., SHANKLEY N.P. International Union of Pharmacology Committee on Receptor Nomenclature and Drug Classification. IX. Recommendations on Terms and Symbols in Quantitative Pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 1995;47:255–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMBERT C., MASSILLON Y., MELOCHE S.Renin-angiotensin system and the congenital cardiomyopathic hamsters mecanisms of heart failure 1995aBoston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 203–214.ed. Signal P.K., Dixon I.M., Beamish, R.B. & Dhalla, N.S. pp [Google Scholar]

- LAMBERT C., MASSILLON Y., MELOCHE S. Upregulation of cardiac angiotensin AT1 receptors in congenital cardiomyopathic hamsters. Circ Res. 1995b;77:1001–1007. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.5.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINZ W., WIEMER G., WIRTH K., SCHÖLKENS B.A.The roles of kinins in the cardiac effects of ACE inhibitors and myocardial ischemia The kinin system 1997Academic Press: London; pp315–323.Farmer, S. G., ed [Google Scholar]

- LOMMI J., PULKKI K., KOSKINEN P., NAVERI H., LEINONEN H., HARKONEN M., KUPARI M. Haemodynamic, neuroendocrine and metabolites correlates of circulating cytokine concentrations in congestive heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 1997;18:1620–1625. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LORTIE M., REGOLI D., RHALEB N.E., PLANTE G. The role of B1 and B2 receptors in the renal tubular and hemodynamic responses to bradykinin. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;262:R72–R76. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.1.R72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCEAU F. Kinin B1 receptors: a review. Immunopharmacology. 1995;30:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(95)00011-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCEAU F., HESS J.F., BACHVAROV D.R. The B1 receptors for kinins. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:357–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATHIS S.A., CRISCIMAGNA N.L., LEEB-LUNDBERG F. B1 and B2 kinin receptors mediate distinct patterns of intracellular Ca2+ signaling in single cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;50:128–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEINI S., LECCI A., MAGGI C.A. The longitudinal muscle of rat ileum as a sensitive monoreceptor assay for bradykinin B1 receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:1619–1624. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NSA ALLOGHO S., GOBEIL F., PERRON S.I., REGOLI D. Effects of kinins on isolated stomachs of control and transgenic knockout B2 receptor mice. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 1998;357:191–196. doi: 10.1007/pl00005157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NSA ALLOGHO S., GOBEIL F., PHENG L.H., NGUYEN-LE X.K., NEUGEBAUER W., REGOLI D. Antagonists for kinin B1 and B2 receptors in the mouse. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1997;75:558–562. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-75-6-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NSA ALLOGHO S., GOBEIL F., PHENG L.H., NGUYEN-LE X.K., NEUGEBAUER W., REGOLI D. Kinin B1 and B2 receptors in the mouse. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1995;73:1759–1764. doi: 10.1139/y95-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REGOLI D., BARABÉ J., PARK W.K. Receptors for bradykinin in rabbit aortae. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1977;55:855–867. doi: 10.1139/y77-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REGOLI D., BARABÉ J. Pharmacology of bradykinin and related kinins. Pharmacol. Rev. 1980;32:1–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REGOLI D., BOUDON A., FAUCHÈRE J.L. Receptors and antagonists for substance P and related peptides. Pharmacol. Rev. 1994a;46:551–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REGOLI D., GOBEIL F., NGUYEN Q.T., JUKIC D., SEOANE P.R., SALVINO P.R., SAWUTZ D.G. Bradykinin receptor types and B2 subtypes. Life Sci. 1994b;55:735–749. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00557-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REGOLI D., NSA ALLOGHO S., RIZZI A., GOBEIL F., JR Bradykinin receptors and their antagonists. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;348:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RHALEB N.E., DION S., BARABÉ J., ROUISSI N., JUKIE D., DRAPEAU G., REGOLI D. Receptors for Kinins in isolated arterial vessels of dogs. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;162:419–427. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIZZI A., GOBEIL F., CALÒ G., INAMURA N., REGOLI D. FR 173657: A new, potent, nonpeptide kinin B2 receptor antagonist. An in vitro study. Hypertension. 1997;29:951–956. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.4.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH J.A.M., WEBB C., HOLFORD J., BURGESS G.M. Signal transduction pathways for B1 and B2 bradykinin receptors in bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;47:525–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TALLARIDA R.J., MURRAY R.B.Manual of Pharmacological Calculations with Computer Programs 1987New York, U.S.A.: Springer Verlag; 145p2nd ed [Google Scholar]