Abstract

Primary cultures of adult rat dorsal root ganglia (DRG) were prepared to examine the properties of prostacyclin (IP) receptors and prostaglandin E2 (EP) receptors in sensory neurones.

IP receptor agonists, cicaprost and iloprost, stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity with EC50 values of 22 and 28 nM, respectively. Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) were 7 fold less potent than cicaprost and iloprost, with PGE2 displaying a lower maximal response.

Adenylyl cyclase activation by iloprost, PGE1 and PGE2, but not by forskolin, was highly dependent on DRG cell density. Although the potency of iloprost and PGE2 for stimulating adenylyl cyclase was unchanged, their maximal responses were significantly increased at low cell density.

Both IP and EP2/4 receptors could be down-regulated by agonist pretreatment, however the presence of cyclo-oxygenase (COX) inhibitors did not prevent this apparent down-regulation of IP and EP2/4 receptors at high DRG cell densities.

Stimulation of adenylyl cyclase by the neuropeptide calcitonin gene-related peptide was also decreased at high DRG cell density, whereas the responses to β-adrenoceptor agonists were increased at high DRG cell density.

Addition of nerve growth factor (NGF), or the addition of anti-neurotrophin antibodies during the 5-day culture of DRG cells, had no effect on IP receptor-mediated responses.

These results indicate that Gs-coupled receptors involved in nociception are regulated in a variable manner in adult rat sensory neurones, and that this cell density-dependent regulation may be agonist-independent for IP and EP2/4 receptors.

Keywords: Prostacyclin, prostaglandin E2, IP receptors, EP receptors, sensory neurones, dorsal root ganglia, receptor regulation

Introduction

Prostacyclin (PGI2) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) both have well recognized roles as hyperalgesic agents due to their ability to sensitize sensory nerve fibres; see reviews by Bley et al. (1998) and Wise & Jones (2000). Until recently, PGE2 has attracted most attention as the key prostaglandin involved in hyperalgesia, but PGI2 has effects comparable with PGE2 as a hyperalgesic or sensitizing agent (Bley et al., 1998). In mice lacking the PGI2 (IP) receptor, inflammatory pain responses are reduced to the level seen in indomethacin-treated animals, and PGI2 administered by intraperitoneal injection, but not PGE2, is a potent inducer of writhing behaviour in mice (Murata et al., 1997). In addition, more recent studies of IP receptor-deficient mice indicates that bradykinin released following intraplantar injection of carrageenan mediates mouse paw oedema via induction of PGI2 formation and activation of IP receptors (Ueno et al., 2000). Both autoradiographic studies of [3H]-iloprost binding in the rat nervous system (Matsumura et al., 1995), and of IP receptor mRNA distribution in the mouse (Oida et al., 1995), indicate a role for IP receptors in sensory neurones such as those of the dorsal root ganglia (DRG).

Sensory neurones from the DRG can be maintained in culture, and have been found to provide a useful in vitro model to study PGI2 and PGE2-mediated sensitization of responses to algesic agents (Gold et al., 1996). The antigenic phenotype of adult rat DRG cells is largely maintained in culture, such that the neuronal subpopulations present in vivo are present in cultures in approximately the same proportions (Gavazzi et al., 1999). However, changes in the peptidergic phenotype in primary sensory neurones does occur in vivo following axotomy (Hökfelt et al., 1994). While the functional consequences of these changes remain undefined, their parallel in DRG cells maintained in culture is even less well defined. The conditions under which isolated DRG cells are maintained in culture are heavily influenced by the experimental test system. Thus, for electrophysiological experiments on ion channels, freshly prepared DRG cells are used (Ueno et al., 1999). For studies on second messengers, 5 days in culture is a common period (Smith et al., 1998) with the addition of nerve growth factor (NGF) to allow expression of bradykinin receptors (Kasai et al., 1998). NGF is also added to maintain the concentration of sensory peptides for neuropeptide release studies (Lindsay et al., 1989) where relatively high concentrations of DRG cells are used.

Prostanoids such as PGI2 and PGE2 activate G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in a wide range of tissues (Narumiya et al., 1999). IP receptors couple primarily to Gs, although they can couple to Gq (Namba et al., 1994) and have been shown to stimulate phospholipase C activity in adult rat DRG cells in vitro (Smith et al., 1998). Receptors for PGE2 have been classified into four major subtypes according to Coleman et al. (1994): EP1 which increases intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, possibly via Gq, EP2 and EP4 which couple to Gs, and EP3 which couples primarily to Gi. Adult rat DRG cells possess EP receptors able to stimulate adenylyl cyclase (Smith et al., 1998), and these are referred to herein as EP2/4 since the lack of suitably selective agonists and antagonists has meant that precise functional classification is not yet possible. Approximately 20 – 40% of the IP receptor mRNA-positive neurones in mouse DRG co-express EP1, EP3 and EP4 receptor mRNA (EP2 mRNA was not examined) (Oida et al., 1995).

GPCRs undergo rapid desensitization following agonist stimulation, with chronic agonist exposure resulting in decreased receptor expression known as down-regulation (Koenig & Edwardson, 1997). The anti-platelet aggregation properties of PGI2 are down-regulated by agonist exposure (Giovanazzi et al., 1997), as are the anti-proliferative effects of the PGI2 analogue iloprost in cultured bovine coronary artery smooth muscle cells (Zucker et al., 1998). For cells with endogenous production of PGI2, such as endothelial cells, this agonist-induced desensitization of IP receptors may be sufficient to limit detection of IP receptor-mediated responses (Schrör, 1993). A similar effect is seen for EP receptors where their detection in the choroidal vasculature of newborn pigs, either by receptor binding or functional studies, is also hampered unless the animals are treated with cyclo-oxygenase (COX) inhibitors prior to experimentation (Abran et al., 1997).

During the course of our studies on prostanoid receptor regulation of DRG cell activity, we noted a marked increase in cyclic AMP production by adult rat DRG cells in response to iloprost when DRG cells were cultured at lower cell densities (Rowlands & Wise, 1999). The aim of this current paper was to examine this phenomenon in more detail and to compare the responses of DRG cells to both IP and EP2/4 agonists. This paper shows that inhibition of COX activity fails to reverse the apparent down-regulation of IP and EP2/4 receptors at high cell densities, and that this down-regulation is not a consistent property of Gs-coupled receptors involved in nociception. In addition, we have attempted to identify the factors responsible for the agonist-independent regulation of IP and EP2/4 receptors in DRG cells.

Methods

Preparation of primary culture of adult rat DRG neurones

The dorsal root ganglia were removed from all levels of the spinal cord of male Sprague-Dawley rats (150 – 200 g) and cultures were prepared based on the method described by Smith et al. (1998). Briefly, rats were anaesthetized with pentobarbitone (40 mg kg−1, i.p.) and dissected following procedures approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of The Chinese University of Hong Kong. DRG were dissected into Ham's F14 medium (Ham's Nutrient Mixture F14 medium containing 4% Ultroser G, 100 units ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin), followed by incubation with 0.125% collagenase (3 h), then 0.25% trypsin (30 min, 37°C, 5% CO2) in serum-free Ham's F14 medium. After rinsing in Ham's F14 medium, the DRG were resuspended in 2 ml 90 μg ml−1 DNase I and 100 μg ml−1 soybean trypsin inhibitor in Ham's F14 medium and the DRG dispersed by trituration with a small-bore, fire-polished Pasteur pipette. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 96×g for 10 min at room temperature through a cushion of 15% bovine serum albumin to eliminate much of the cellular debris and produce a neuronally enriched pellet of dissociated neurones (Gavazzi et al., 1999). The cell pellet was resuspended in Ham's F14 medium containing 50 ng ml−1 NGF and 10 μM arabinoside C to inhibit non-neuronal cell proliferation. Cells were plated onto 24-well tissue culture plates (Nunc) precoated with poly-DL-ornithine (500 μg ml−1) and laminin (5 μg ml−1) and maintained in culture for 5 days in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Measurement of [3H]-cyclic AMP production

After an overnight incubation (18 h) with [3H]-adenine (2 μCi ml−1; 1 μCi well−1), the medium was aspirated and the cells washed twice with 1 ml HEPES-buffered saline (HBS (mM): HEPES 25, pH 7.4, NaCl 135, KCl 3.5, CaCl2 2.5, MgCl2 1.0, glucose 3.3). Cells were challenged with test compounds for 30 min at 37°C in assay buffer (HBS containing 1 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methyl xanthine (IBMX) to inhibit phosphodiesterase activity, and 3 μM indomethacin to inhibit tonic prostanoid synthesis). The reaction was stopped by addition of ice-cold trichloroacetic acid and ATP, at a final concentration of 5% and 1 mM, respectively. The plates were left for at least 30 min on ice before separating the [3H]-cyclic AMP from [3H]-ATP by column chromatography (Barber et al., 1980). Cell samples were loaded onto Dowex AG50W-X4 (200 – 400 mesh) columns and [3H]-ATP eluted with 3 ml distilled water. A further 10 ml distilled water was added and the eluant loaded directly onto a neutral alumina column, which was eluted with 6 ml 0.1 M imidazole buffer, pH 7.5, to give a fraction containing [3H]-cyclic AMP. Scintillator (OptiPhase ‘HiSafe' 3, 10 ml) was added for scintillation counting.

The production of [3H]-cyclic AMP from cellular [3H]-ATP in the presence of a phosphodiesterase inhibitor (i.e. adenylyl cyclase activity) was estimated as the ratio of radiolabelled cyclic AMP to total AXP (i.e. cyclic AMP, ADP and ATP), and is expressed as [cyclic AMP]/[total AXP]×1000. The absolute basal values for [3H]-cyclic AMP production at each DRG cell density are indicated in the Figure and Table legends. All assays were performed in triplicate where s.e.mean values were typically less than 10% of the mean values. Solvent controls were run as appropriate, but neither dimethylsulphoxide nor ethanol interfered with the assay at the concentrations used.

Measurement of 6-keto PGF1α and PGE2

After 5 days in culture, the media was removed from the cultured DRG cells, lyophilized, and assayed for 6-keto PGF1α and PGE2 by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Data analysis

Values for EC50 and Emax, the maximum effect, were obtained by fitting the log concentration-response curves to the standard four-parameter logistic equation using GraphPad Prism software version 3.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, U.S.A.):

where E is the measured response, Emin and Emax are the minimum and maximum asymptotes, EC50 is obtained from the ‘location parameter' of the curve, x is the concentration and n is the slope factor of the curve (‘Hill slope'). pEC50 is the negative logarithm of the EC50 value for stimulation of adenylyl cyclase activity. Fold basal activity is stimulated [3H]-cyclic AMP production divided by basal [3H]-cyclic AMP production. Values reported are means±standard error mean. Comparisons between groups were made using the Student's t-test or ANOVA with Bonferroni's post-tests, as appropriate. Statistical significance is taken as P<0.05.

Drugs

Cicaprost and iloprost were gifts from Schering AG, Berlin, Germany. 8-[3H]-adenine (specific activity 27 Ci mmol−1) was purchased from Amersham (Far East) Trading Ltd. Dowex AG 50W-XA (200 – 400 mesh) was purchased from Bio-Rad (U.S.A.), and OptiPhase ‘HiSafe' 3 scintillant from Pharmacia Biotech Far East Ltd. Collagenase B and trypsin were purchased from Roche Diagnostics (U.S.A.), Ham's Nutrient Mixture F14 from Imperial Laboratories (U.K.), and nerve growth factor (mouse 2.5s) from Alomone Labs. (Israel). Anti-neurotrophin antibodies were from Chemicon (U.S.A.), and 6-keto PGF1α and PGE2 EIA kits from Cayman Chemical (U.S.A.). All other compounds were supplied by Gibco (U.S.A.) or Sigma Chemical Co. (U.S.A.).

Results

Effect of prostanoids on [3H]-cyclic AMP production

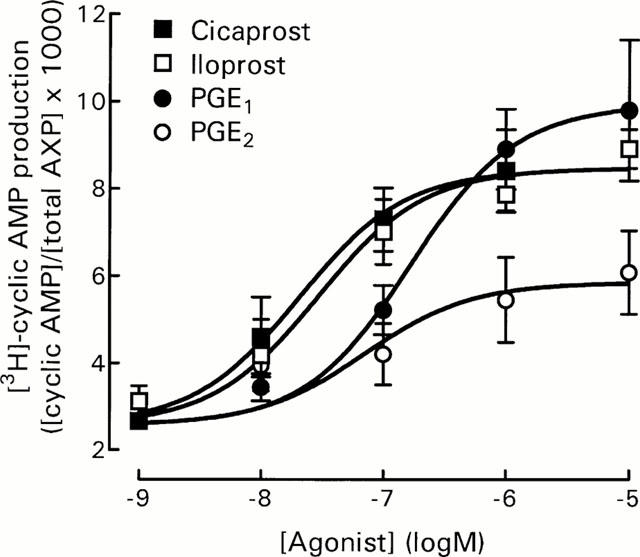

The prostanoid agonists cicaprost, iloprost, PGE1 and PGE2 stimulated [3H]-cyclic AMP production with pEC50 values of 7.65±0.34, 7.55±0.22, 6.73±0.21 and 6.78±0.29 (n=4 – 5), respectively (Figure 1). Maximum [3H]-cyclic AMP production ([cAMP]/[total AXP]×1000) was 8.51±0.32, 8.90±0.91, 10.31±1.63 and 6.09±0.92 for cicaprost, iloprost, PGE1 and PGE2, respectively. All log concentration-response curves were best fitted with a slope value of one. Maximal stimulation by the non-receptor activator of adenylyl cyclase, forskolin (Laurenza et al., 1989), was at least 10 fold greater than that of the receptor agonists, with a pEC50 value of approximately 4.34 (n=5). Concentrations of 50 or 75 nM forskolin were used in subsequent experiments to match the adenylyl cyclase activating responses of the receptor agonists.

Figure 1.

Effect of prostanoids on [3H]-cyclic AMP production by DRG cells. Cells were incubated at 15,000 cells well−1 in HBS containing IBMX (1 mM) and indomethacin (3 μM) as described in Methods. Data represent mean±s.e.mean of 4 – 5 experiments, each performed in triplicate. Basal [3H]-cyclic AMP production ([cAMP]/[total AXP]×1000) was 2.57±0.12, n=6.

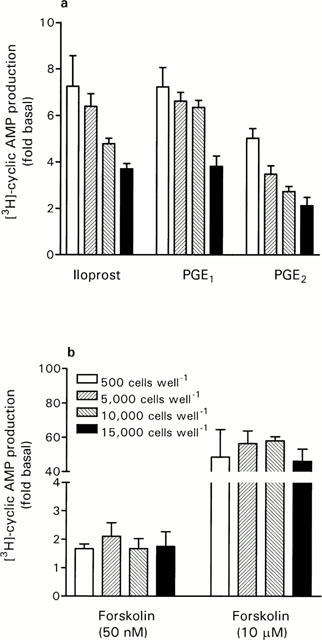

Influence of cell density on [3H]-cyclic AMP production

When DRG cells were plated out at different densities, decreasing the DRG cell density from 15,000 cells well−1 through 10,000 and 5000 cells well−1 to 500 cells well−1 produced a highly significant (P<0.001, two-way ANOVA) increase in agonist-stimulated [3H]-cyclic AMP production (Figure 2a). Although basal adenylyl cyclase activity in the 500 cells well−1 group was significantly lower than the 5000 and 10,000 cells well−1 groups (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post-tests, see Figure 2 legend), this does not entirely account for the change in fold basal values shown in Figure 2a, because forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity was clearly unaffected under the same conditions (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Effect of DRG cell density on responses to activators of adenylyl cyclase. DRG cells were plated at 500, 5000, 10,000 and 15,000 cells well−1, and [3H]-cyclic AMP production assayed in response to iloprost (10 μM), PGE1 (10 μM), PGE2 (10 μM) and forskolin (50 nM and 10 μM). Basal [3H]-cyclic AMP production ([cAMP]/[total AXP]×1000) for each condition was: 500 cells, 2.00±0.19*; 5000 cells, 3.51±0.35; 10,000 cells, 3.46±0.39 and 15,000 cells, 3.01±0.26. *P<0.05 compared with 5000 and 10,000 cells well−1 groups, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post-tests. Data represent mean±s.e.mean of 3 – 6 experiments, each performed in triplicate.

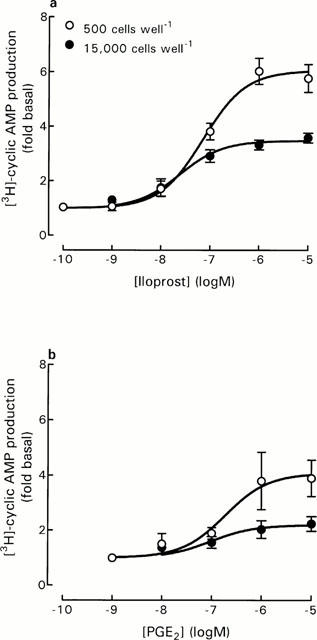

To determine if the increased responsiveness of DRG cells at low cell number represented a change in agonist potency and/or maximum response to agonists, concentration-response curves for iloprost and PGE2 were obtained using DRG cells at 500 cells well−1 and compared with data from 15,000 cells well−1 (Figure 3). The decreased cell density did not affect the potency of iloprost with pEC50 values of 7.09±0.01 (n=3), and 7.55±0.23 (n=4) for 500 and 15,000 cells well−1, respectively. Maximum responses to iloprost (calculated as fold basal values) were however significantly different (P<0.001, Student's t-test) at 6.03±0.38 and 3.36±0.14 for 500 and 15,000 cells well−1, respectively.

Figure 3.

Effect of iloprost and PGE2 on DRG cell responses at different cell densities. For iloprost concentration-response curves, basal [3H]-cyclic AMP production ([cAMP]/[total AXP]×1000) was 2.16±0.27 and 2.29±0.36 for 500 and 15,000 cells well−1, respectively. For PGE2 concentration-response curves, basal [3H]-cyclic AMP production ([cAMP]/[total AXP]×1000) was 1.62±0.16 and 2.69±0.23 for 500 and 15,000 cells well−1, respectively (P<0.05, Student's t-test). Data represent mean±s.e.mean of 3 – 4 experiments, each performed in triplicate.

The decreased cell density also did not affect the potency of PGE2 with pEC50 values of 6.59±0.17 (n=4), and 6.78±0.29 (n=4) for 500 and 15,000 cells well−1, respectively. Maximum responses to PGE2 (calculated as fold basal values) were also significantly different (P<0.001, Student's t-test) at 4.28±0.81 and 2.25±0.25 for 500 and 15,000 cells well−1, respectively.

Investigation of factors which might influence adenylyl cyclase responses

Activation of prostanoid receptors coupled to Gi proteins

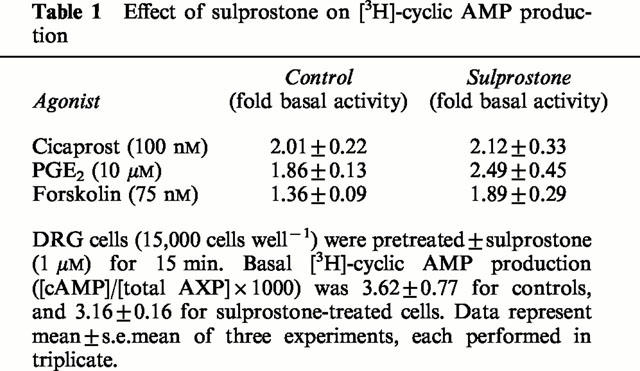

DRG cells at 15,000 cells well−1 were incubated for 15 min with 1 μM sulprostone (EP1/EP3 agonist) before addition of cicaprost, PGE2 or forskolin (Table 1). Sulprostone alone had no effect on basal [3H]-cyclic AMP production, and failed to inhibit stimulated [3H]-cyclic AMP production.

Table 1.

Effect of sulprostone on [3H]-cyclic AMP production

Agonist-induced down-regulation

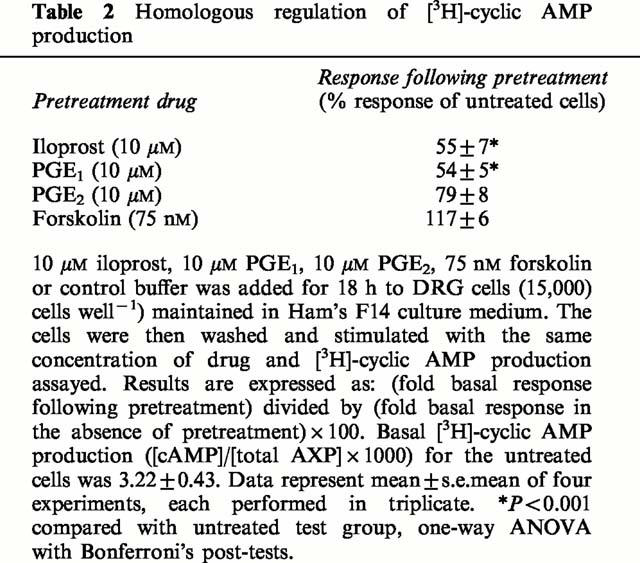

Pretreatment of DRG cells with high concentrations of IP and EP agonists for 18 h produced a significant down-regulation of their ability to respond further to stimulation by the same agonist (Table 2). Forskolin acts directly on adenylyl cyclase and therefore failed to produce homologous desensitization (Table 2). A similar pattern of responses was obtained for DRG cells at the lower cell density of 500 cells well−1; pretreatment with the same adenylyl cyclase activator produced an inhibition of 46% for 10 μM iloprost, 56% for 10 μM PGE1, 29% for 10 μM PGE2 and 0% for 75 nM forskolin (data from two experiments, each performed in triplicate).

Table 2.

Homologous regulation of [3H]-cyclic AMP production

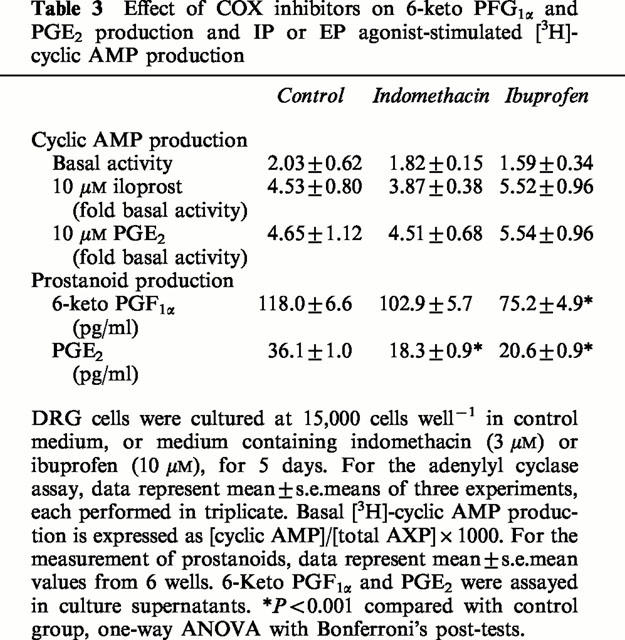

We therefore included the non-selective COX inhibitors indomethacin and ibuprofen for the 5 days of DRG cell culture to look for any influence from endogenously-produced prostanoids. The Ham's F14 medium was supplemented with 3 μM indomethacin, 10 μM ibuprofen or solvent control, and these agents were re-applied after 2 days. After a total of 5 days, the production of 6-keto PGF1α (the stable metabolite of PGI2) and PGE2 was determined by EIA, and adenylyl cyclase activity in response to 10 μM iloprost and 10 μM PGE2 was determined. Although the COX inhibitors produced a significant reduction in 6-keto PGI1α and PGE2 production by DRG cells in culture, there was no significant effect on the ability of iloprost or PGE2 to stimulate the production of [3H]-cyclic AMP (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of COX inhibitors on 6-keto PFG1α and PGE2 production and IP or EP agonist-stimulated [3H]-cyclic AMP production

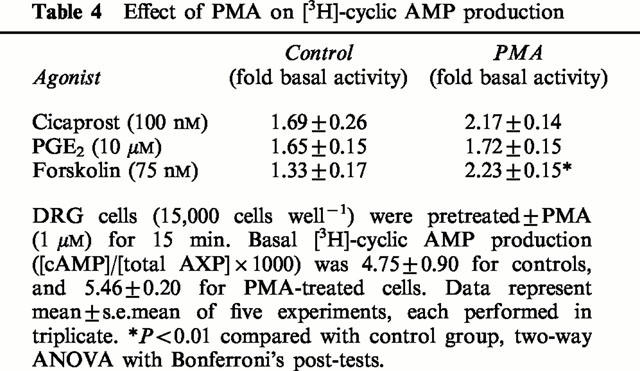

Effect of protein kinase C activation

DRG cells at 15,000 cells well−1 were incubated with 1 μM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 15 min before the addition of cicaprost, PGE2 or forskolin (Table 4). Although PMA appeared to increase the adenylyl cyclase response to cicaprost, this was not a statistically significant effect. There was however no evidence to suggest that PMA could decrease the response to PGE2. As noted previously by Smith et al. (1998), phorbol esters significantly increased forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase in DRG cells.

Table 4.

Effect of PMA on [3H]-cyclic AMP production

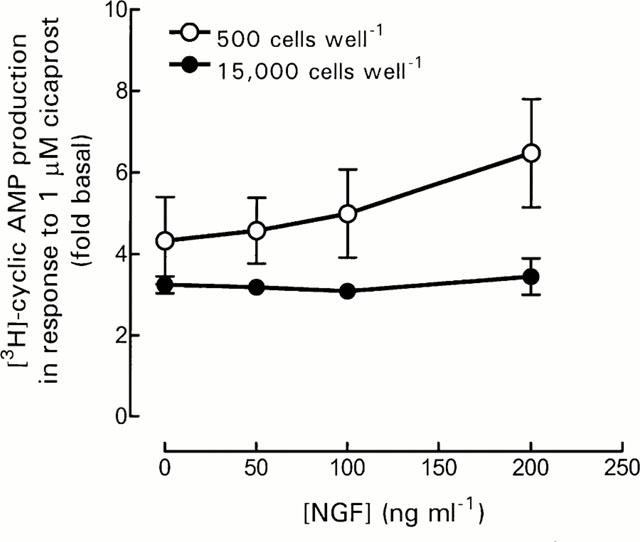

Effect of nerve growth factor

DRG cell cultures (500 and 15,000 cells well−1) were maintained in NGF-containing and NGF-free Ham's F14 medium for 5 days. Increasing the concentration of exogenous NGF from 0 to 200 ng ml−1, failed to modify the responsiveness of DRG cells, at either cell density, to 1 μM cicaprost (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of NGF on DRG cell responsiveness. DRG cells were cultured for 5 days in Ham's F14 medium with increasing concentration of NGF. Cells were washed and stimulated with 1 μM cicaprost, and [3H]-cyclic AMP production assayed as described in Methods. Basal [3H]-cyclic AMP production ([cAMP]/[total AXP]×1000) was 1.78±0.12, 1.81±0.23, 1.60±0.14 and 1.49±0.20 for 0, 50, 100 and 200 ng ml−1 NGF, respectively, for 500 cells well−1. Basal [3H]-cyclic AMP production ([cAMP]/[total AXP]×1000) was 1.41±0.25, 1.54±0.22, 1.66±0.31 and 1.77±0.35 for 0, 50, 100 and 200 ng ml−1 NGF, respectively, for 15,000 cells well−1. Data represent mean±s.e.mean of three experiments, each performed in triplicate.

Effect of anti-neurotrophin antibodies

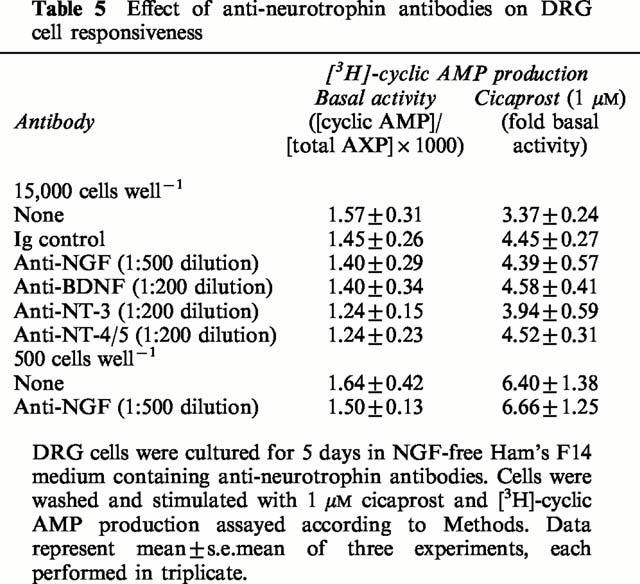

To determine if DRG cells at 15,000 cells well−1 produce a neurotrophic factor capable of down-regulating IP and EP2/4 receptors, we maintained DRG cell cultures (15,000 cells well−1) in NGF-free Ham's F14 medium plus anti-neurotrophin antibodies for 5 days. Anti-mouse NGF, anti-human brain-derived neurotrophin (BDNF), anti-human neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) and anti-human neurotrophin-4/5 (NT-4/5) antibodies were used at the supplier's recommended dilutions to specifically neutralize any endogenously-produced neurotrophins. None of the anti-neurotrophin antibodies used significantly modified the adenylyl cyclase response to 1 μM cicaprost above the level of the control antibody (Table 5). Anti-NGF antibodies were also tested in DRG cells at 500 cells well−1 in comparison to the absence of exogenous NGF, but again there was a lack of effect on the response to cicaprost (Table 5).

Table 5.

Effect of anti-neurotrophin antibodies on DRG cell responsiveness

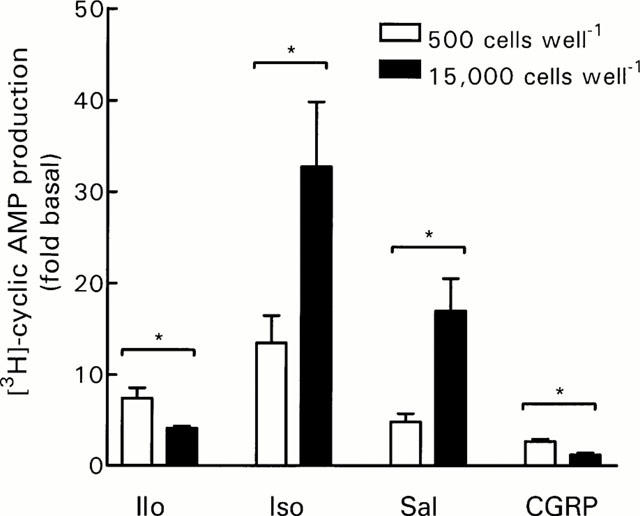

Effect of DRG cell density on non-prostanoid receptor agonists

To determine if the responsiveness of DRG cells to other agonists involved in nociception was also influenced by DRG cell density, we examined the effect of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), isoprenaline and salbutamol which stimulate Gs-coupled receptors. While the response to CGRP was also increased by decreasing the cell density from 15,000 to 500 cells well−1, the responses to the non-selective β-adrenoceptor agonist isoprenaline and the selective β2-adrenoceptor agonist salbutamol showed the opposite effect and were decreased as cell numbers decreased (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of DRG cell density on [3H]-cyclic AMP production in response to non-prostanoid receptor agonists. Cells were incubated in HBS containing IBMX (1 mM) and indomethacin (3 μM) as described in Methods. Data represent mean±s.e.mean of 4 – 5 experiments, each performed in triplicate. Iloprost (Ilo, 10 μM), isoprenaline (Iso, 1 μM), salbutamol (Sal, 1 μM) and CGRP (1 μM). Basal [3H]-cyclic AMP production ([cAMP]/[total AXP]×1000) was 1.96±0.28 and 2.58±0.24 for 500 and 15,000 cells well−1, respectively. *P<0.05, Student's t-test.

Discussion

Although cicaprost and iloprost are commonly used as IP agonists (Wise & Jones, 2000), their non-selectivity could result in stimulation of [3H]-cyclic AMP production in DRG cells via activation of rat EP4 receptors (Boie et al., 1997). However, the potency of cicaprost and iloprost for stimulating [3H]-cyclic AMP production in rat DRG cells is much more suggestive of an action at IP receptors, as reported previously by Smith et al. (1998), and as supported by observations on the extent of [3H]-iloprost binding (Matsumura et al., 1995) and IP receptor mRNA distribution in dorsal root ganglia (Oida et al., 1995). The potency of PGE1 for stimulating adenylyl cyclase activity in DRG cells is only 10 fold lower than that of cicaprost and iloprost, and PGE1 has comparable maximal effects to cicaprost and iloprost, as would be expected if PGE1 is acting here on rat IP receptors (Sasaki et al., 1994). Iloprost additionally is a potent agonist at EP1 receptors (Dong et al., 1986) where it would be expected to increase intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. However, the log concentration-response curves for cicaprost and iloprost are practically superimposable, indicating that the EP1 agonist property of iloprost does not interfer with its ability to stimulate adenylyl cyclase in DRG cells.

In addition to stimulating EP2/4 receptors, PGE2 can also interact with rat IP receptors, at concentrations approximately 300 fold higher than its Kd for the rat EP2 and EP4 receptors (Sasaki et al., 1994). Therefore, the relatively low potency and low maximal response of PGE2 could suggest that it is acting at IP receptors and/or EP2 or EP4 receptors at low level expression, but the lack of specific antagonists for IP and EP receptors prevents full clarification of this issue at the present time.

GPCRs undergo agonist-induced desensitization (Koenig & Edwardson, 1997), and this is a well-established characteristic of IP receptors in cells such as NG108-15 neuroblastoma cells and platelets (Jaschonek et al., 1988; Kelly et al., 1990). Results presented in the current study using DRG cells would suggest that down-regulation of IP and EP2/4 receptors is inversely related to the cell density. To account for the different extent of metabolic labelling of DRG cells plated at different densities, we have calculated [3H]-cyclic AMP production as [cAMP]/[AXP]×1000, rather than simply use the d.p.m. values for the [3H]-cyclic AMP fractions collected. In the majority of experiments, the basal levels of [3H]-cyclic AMP production were not affected by cell density (see Figures 3a, 4, 5 and Table 5), presumably indicating that the metabolic activity of these cells was similar. However, for the data in Figure 2, even though there was no significant difference in the basal adenylyl cyclase activity between DRG cells plated at 500 and 15,000 cells well−1, or between the 5000, 10,000 and 15,000 cells well−1 groups, basal adenylyl cyclase activity was significantly lower in the 500 compared with the 5000/10,000 cells well−1 groups. This latter result over emphasises the increased responses seen at 500 cells well−1 when results are expressed as fold basal; a necessary procedure to standardize for the variability between different batches of DRG cells. However, when expressing results as fold basal, significant differences in maximal responses to cicaprost and iloprost are still demonstratable in the absence of decreases in basal [3H]-cyclic AMP production in the 500 cells well−1 groups (see Figures 3a, 4, 5 and Table 5).

[3H]-cyclic AMP production in response to a low concentration of forskolin showed a slight cell density-dependent effect, but the pattern did not parallel that seen with the prostanoid agonists, and was absent when the results were expressed relative to the basal level of adenylyl cyclase activity. Moreover, [3H]-cyclic AMP production in response to a higher concentration of forskolin showed no obvious cell density-dependent properties. Therefore, we believe that the changes observed for iloprost, PGE1 and PGE2-mediated responses are due to altered receptor availability and/or altered receptor-G protein coupling, rather than changes in adenylyl cyclase function.

The lack of effect of cell density on agonist potency despite the altered maximal responses to iloprost and PGE2 together suggest that we are looking at down-regulation of IP and EP2/4 receptors in high-density cultures of DRG cells. Indeed, in our DRG cell cultures at both low and high cell density, IP and EP2/4 receptors demonstrated homologous desensitization; this agonist-induced desensitization or down-regulation is frequently associated with phosphorylation of the receptor. Studies on HEK 293 cells transfected with the human IP receptor indicate that agonist-dependent phosphorylation of the human IP receptor occurs via protein kinase C (Smyth et al., 1996), resulting in desensitization of both the cyclic AMP and inositol phosphate responses to iloprost (Smyth et al., 1998). Rat IP receptors have an additional protein kinase A phosphorylation site (Sasaki et al., 1994), but its role in IP receptor regulation has not been reported. The rat EP2 and EP4 receptors can be phosphorylated by both protein kinase A and protein kinase C (Boie et al., 1997), and although they differ in their susceptibility to agonist-induced short-term desensitization, both EP receptors display similar patterns of down-regulation in response to prolonged exposure to PGE2 (Nishigaki et al., 1996).

We have confirmed the results of Smith et al. (1998) showing that activation of protein kinase C increases adenylyl cyclase responses to forskolin, but its effect on receptor agonists was rather weak. Part of the difficulty in interpreting the results here could lie in the presence of different isoforms of adenylyl cyclase in the various cell types comprising the DRG cell preparation. All these isoforms would be responsive to forskolin, but not all would respond in the same manner to protein kinase C activators (Tang & Hurley, 1998). Furthermore, activation of protein kinase C is known to produce variable effects on prostanoid receptor responses. Phorbol esters increase cicaprost-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity in UMR-106 osteoblast cells (Khanin et al., 1999) yet have no effect on NG108-15 neuroblastoma cells (Krane et al., 1994). EP2 receptors in both rat neonatal microglial cultures (Patrizio et al., 2000), and in UMR-106 cells (Khanin et al., 1999) are inhibited by phorbol esters. Clearly the situation of agonist-dependent receptor phosphorylation in DRG cells is likely to be complex, and further studies may reveal subtle differences here between rat IP and EP2/4 receptors.

IP receptors possess an isoprenylation site in their C-terminal tails, and this is essential for coupling to adenylyl cyclase and phospholipase C pathways (Hayes et al., 1999). However, it is also unlikely that the observed down-regulation of IP and EP2/4 receptors in DRG cells is due to inhibition of isoprenylation because EP receptors, indeed all other prostanoid receptors, lack isoprenylation sites. Increased expression and activation of a prostanoid receptor with opposing effects, i.e. the EP3 receptor, might account for the reduced maximum responses to IP agonists and PGE2 at higher cell densities. By definition, PGE2 would be expected to stimulate all subtypes of EP receptors, and indeed has similar affinity for the rat EP4 and EP3 receptors (Boie et al., 1997). In addition, concentrations of 1 μM cicaprost and iloprost are also likely to stimulate EP3 receptors (Boie et al., 1997; Kiriyama et al., 1997). However, we have excluded the possible stimulation by IP agonists and PGE2 of inhibitory EP3 receptors at high DRG cell density because sulprostone failed to inhibit cicaprost, PGE2 and forskolin-stimulated [3H]-cyclic AMP production. These results confirm those of Smith et al. (1998) demonstrating a lack of functional EP3 receptors in rat isolated DRG cell preparations. Furthermore, the prostanoid receptor data alone might suggest that high-density DRG cell preparations produce a factor/s capable of stimulating an alternative Gi-coupled pathway. However, such a factor should similarly affect the responses to forskolin, isoprenaline and salbutamol, and this is clearly not the case.

As suggested above, a typical DRG cell preparation contains not only neuronal cells, but also non-neuronal cells such as astrocytes and Schwann cells. Our current experimental design does not allow us to distinguish the cellular source of cyclic AMP, but all cell counts are based on the morphologically distinct neuronal cell component of our DRG cell preparation. Evidence for the presence of IP and EP2/4 receptors in glial cells, rather than neuronal cells, is contradictory. For example, there is no evidence for IP receptor mRNA in mouse glial cells (Oida et al., 1995), or human glioblastoma cell lines (Verity et al., 1999), yet IP receptors, but not EP2/4 receptors, have been identified in newborn rat astroglial cell cultures (Seregi et al., 1988). Furthermore, there is minimal activation of adenylyl cyclase by iloprost in human astrocytoma cells (Ortmann, 1978), and in primary cultures of rat type-1 and type-2 astrocytes (Ito et al., 1992).

In rat aorta there is a clear inverse relationship between PGI2 synthase mRNA and 6-keto PGF1α production, and the expression of IP receptor mRNA (Numaguchi et al., 1999). Recent studies provide immunohistochemical evidence of PGI2 synthase in the central nervous system, within neuronal rather than non-neuronal cells (Mehl et al., 1999), however, preliminary data suggests a lack of PGI2 synthase in neuronal cells of adult rat DRG (Hans-J. Bidmon, personal communication). IP and EP receptors are often down-regulated in normal cell systems, and detected clearly only after use of COX inhibitors to inhibit the endogenous production of prostanoids, as is the case for endothelial cells (Schrör, 1993), and the choroidal vasculature (Abran et al., 1997). Pretreatment of rat DRG cells in culture with non-selective COX inhibitors failed to increase the response to either iloprost or PGE2. Indeed, the concentration of prostanoids released into the culture medium of our DRG cell preparation was in the low picomolar range, which would be insufficient to stimulate IP and EP2/4 receptors and therefore unlikely to cause receptor down-regulation. These results suggest that the cell density-dependent down-regulation of IP and EP2/4 receptors is independent of endogenously-produced ligands.

Since endogenously-produced prostanoids do not appear to be responsible for receptor down-regulation at high cell densities, then perhaps some factor is responsible for up-regulation of prostanoid receptors at low cell densities. For example, IP receptor expression is induced by tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα) in mouse osteoblastic cells (MC3T3-E1) (Wang et al., 1999). Actually, this effect of TNFα was suppressed by COX inhibition, suggesting that it is in part mediated by prostaglandins and is therefore unlikely to provide a mechanism to explain our results.

Neurones from adult DRG can survive independently of trophic factors (Lindsay, 1988; Gavazzi et al., 1999), but NGF is routinely included in our DRG cell cultures because it is reported to maintain the concentration of sensory neuropeptides such as CGRP and substance P (Lindsay et al., 1989). NGF can increase the sensitivity to bradykinin in capsaicin-sensitive DRG cells (Kasai et al., 1998); an effect probably mediated via the low affinity neurotrophin receptor p75 (Petersen et al., 1998). In addition, NGF enhances neurite outgrowth (Gavazzi et al., 1999) and inhibiting the action of endogenously-produced NGF decreases capsaicin sensitivity of isolated DRG cells (Bevan & Winter, 1995; Nicholas et al., 1999). NGF can differentially regulate the expression of a variety of GPCRs in pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells where it decreases adenosine A2A (Lee et al., 1995; Nie et al., 1999), secretin (Lee et al., 1995) and angiotensin II type 2 (AT2-R) (Kijima et al., 1995) receptors, and up-regulates muscarinic m4 (Lee & Malek, 1998) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) receptors (Cavallaro et al., 1995). However, we have found no evidence for regulation of IP receptors in DRG cells by NGF. Furthermore, the ability of PGE2 to increase cyclic AMP levels, and its ability to sensitize rat DRG cells to capsaicin, is also unaffected by NGF (Southall & Vasko, 2000).

Approximately 40% of DRG neurones express both the high affinity, NGF-selective tyrosine kinase receptor trkA and CGRP, and are therefore considered to be nociceptive neurones (Snider & Wright, 1996). Of the remaining small to medium-sized cells, most express trkB, the receptor for BDNF and NT-4/5, while the larger proprioceptive neurones express trkC, the receptor for NT-3. Neurotrophins can be produced by target cells, supportive cells, and by the neuronal cells themselves (Dray, 1996). Indeed, BDNF may have an autocrine role in the survival of a subpopulation of DRG cells since BDNF (and NT-3 or NT-4/5, but not NGF) can rescue adult rat DRG cells treated with antisense oligonucleotides to BDNF (Acheson et al., 1995). In the present study, culture of DRG cells in the presence of antibodies capable of specifically neutralizing BDNF, NGF, NT-3 or NT-4/5, had no influence on the response of DRG cells to cicaprost. Thus, while neurotrophins may influence neurite outgrowth, neuropeptide content, or capsaicin-sensitivity of DRG cells, they do not appear to influence responsiveness to the hyperalgesic prostanoids, PGI2 and PGE2.

Although it is well recognized that the chemical environment in which DRG cells are maintained is likely to influence their behaviour in culture (Dray, 1996), the marked influence of cell density has been less well recognized. A recent report shows that cell density influences the expression of neuropeptide Y (NPY) in isolated adult rat DRG cells, where fewer neurones express NPY in high rather than low density cultures (Kerekes et al., 2000). Predicting the influence of cell density on neuropeptide content and receptor expression levels of DRG cells in vitro is not yet possible. For example, we tested the neuropeptide CGRP because it acts as an autoreceptor on primary afferents (Levine et al., 1993) and would be expected to increase cyclic AMP production (Wimalawansa, 1992). As observed for IP and EP2/4 agonists, adenylyl cyclase responses to CGRP were also inhibited at high cell density. In contrast, the responses to isoprenaline and salbutamol increased at high cell density. These β-agonists were tested because adrenaline can also produce cyclic AMP-dependent hyperalgesia and nociceptor sensitizing effects in the rat (Khasar et al., 1999). Thus, we have shown here that GPCRs involved in nociception behave in an unpredictable cell density-dependent fashion.

Although the neuronal subpopulations present in DRG in vivo are thought to be present in isolated cultures in approximately the same proportions (Gavazzi et al., 1999), it is difficult to compare the relative densities of cells in the two situations. Therefore, as isolated adult rat DRG cell preparations are becoming increasingly popular for the study of algesic and hyperalgesic agents, we should perhaps be more cautious when looking at interactions between different receptor systems when the assay systems require different densities of DRG cells.

In conclusion, the responsiveness of Gs protein-coupled receptors in isolated DRG cell preparations is system-dependent. For IP and EP2/4 receptors, this cell density-dependent regulation of GPCR responses seems to be agonist-independent, and does not depend on the presence of neurotrophins.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Jan Smith (Roche Bioscience, U.S.A.) and Dr Gillian Burgess and colleagues (Novartis, U.K.) for advice on the culture of DRG cells, and Dr Hans-J. Bidmon (Heinrich Heine-University Düsseldorf, Germany) for permission to use his preliminary data on PGI2 synthase in rat DRG. The gifts of cicaprost and iloprost (Schering, Germany) are gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong.

Abbreviations

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CGRP

calcitonin gene-related peptide

- COX

cyclo-oxygenase

- DRG

dorsal root ganglia

- EIA

enzyme immunoassay

- GPCRs

G protein-coupled receptors

- HBS

HEPES-buffered saline

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methyl xanthine

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- NT-3

neurotrophin-3

- NT-4/5

neurotrophin-4/5

- PGI2

prostacyclin

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- TNFa

tumour necrosis factor-α

References

- ABRAN D., DUMONT I., HARDY P., PERI K., LI D.Y., MOLOTCHNIKOFF S., VARMA D.R., CHEMTOB S. Characterization and regulation of prostaglandin E2 receptor and receptor-coupled functions in the choroidal vasculature of the pig during development. Circ. Res. 1997;80:463–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACHESON A., CONOVER J.C., FANDL J.P., DE CHIARA T.M., RUSSELL M., THADANI A., SQUINTO S.P., YANCOPOULOS G.D., LINDSAY R.M. A BDNF autocrine loop in adult sensory neurons prevents cell death. Nature. 1995;374:450–453. doi: 10.1038/374450a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARBER R., RAY K.P., BUTCHER R.W. Turnover of adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate in WI-38 cultured fibroblasts. Biochemistry. 1980;19:2560–2567. doi: 10.1021/bi00553a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEVAN S., WINTER J. Nerve growth factor (NGF) differentially regulates the chemosensitivity of adult rat cultured sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:4918–4926. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-04918.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLEY K.R., HUNTER J.C., EGLEN R.M., SMITH J.A.M. The role of IP prostanoid receptors in inflammatory pain. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:141–147. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOIE Y., STOCCO R., SAWYER N., SLIPETZ D.M., UNGRIN M.D., NEUSCHÄFER-RUBE F., METTERS K.M., ABRAMOVITZ M. Molecular cloning and characterization of the four rat prostaglandin E2 prostanoid receptor subtypes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;340:227–241. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAVALLARO S., D'AGATA V., GUARDABASSO V., TRAVALI S., STIVALA F., CANONICO P.L. Differentiation induces pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide receptor expression in PC-12 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;48:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLEMAN R.A., SMITH W.L., NARUMIYA S. International Union of Pharmacology classification of prostanoid receptors: Properties, distribution and structure of the receptors and their subtypes. Pharmacol. Rev. 1994;46:205–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRAY A. Chemosensitivity of cultured dorsal root ganglia cells. News Physiol. Sci. 1996;11:288–292. [Google Scholar]

- DONG Y.J., JONES R.L., WILSON N.H. Prostaglandin E receptor subtypes in smooth muscle: agonist activities of stable prostacyclin analogues. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1986;87:97–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAVAZZI I., KUMAR R.D.C., MCMAHON S.B., COHEN J. Growth responses of different subpopulations of adult sensory neurons to neurotrophic factors in vitro. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:3405–3414. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIOVANAZZI S., ACCOMAZZO M.R., LETARI O., OLIVA D., NICOSIA S. Internalization and down-regulation of the prostacyclin receptor in human platelets. Biochem. J. 1997;325:71–77. doi: 10.1042/bj3250071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLD M.S., DASTMALCHI S., LEVINE J.D. Co-expression of nociceptor properties in dorsal root ganglion neurons from the adult rat in vitro. Neuroscience. 1996;71:265–275. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00433-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYES J.S., LAWLER O.A., WALSH M.-T., KINSELLA B.T. The prostacyclin receptor is isoprenylated. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:23707–23718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HÖKFELT T., ZHANG X., WIESENFELD-HALLIN Z. Messenger plasticity in primary sensory neurons following axotomy and its functional implications. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:22–30. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO S., SUGAMA K., INAGAKI N., FUKUI H., GILES H., WADA H., HAYAISHI O. Type-1 and type-2 astrocytes are distinct targets for prostaglandins D2, E2, and F2α. Glia. 1992;6:67–74. doi: 10.1002/glia.440060109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JASCHONEK K., FAUL C., SCHMIDT H., RENN W. Desensitization of platelets with iloprost. Loss of specific binding sites and heterologous desensitization of adenylate cyclase. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1988;147:187–196. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90777-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KASAI M., KUMAZAWA T., MIZUMURA K. Nerve growth factor increases sensitivity to bradykinin, mediated through B-2 receptors, in capsaicin-sensitive small neurons cultured from rat dorsal root ganglia. Neurosci. Res. 1998;32:231–239. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(98)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KELLY E., KEEN M., NOBBS P., MACDERMOT J. Segregation of discrete Gsα-mediated responses that accompany homologous or heterologous desensitization in two related somatic hybrids. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1990;99:309–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEREKES N., LANDRY M., LUNDMARK K., HÖKFELT T. Effect of NGF, BDNF, bFGF, aFGF and cell density on NPY expression in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurones. J. Autonomic Nervous System. 2000;81:128–138. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(00)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KHANIN M., LIEL Y., RIMON G. Differential effect of TPA on PGE2 and cicaprost-induced cAMP synthesis in UMR-106 cells. Cell. Signal. 1999;11:165–169. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(98)00052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KHASAR S.G., MCCARTER G., LEVINE J.D. Epinephrine produces a β-adrenergic receptor-mediated mechanical hyperalgesia and in vitro sensitization of rat nociceptors. J. Neurophysiol. 1999;81:1104–1112. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.3.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIJIMA K., MATSUBARA H., MURASAWA S., MARUYAMA K., MORI Y., INADA M. Gene transcription of angiotensin II type 2 receptor is repressed by growth factors and glucocorticoids in PC12 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;216:359–366. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRIYAMA M., USHIKUBI F., KOBAYASHI T., HIRATA M., SUGIMOTO Y., NARUMIYA S. Ligand binding specificities of the eight types and subtypes of the mouse prostanoid receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:217–224. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOENIG J.A., EDWARDSON J.M. Endocytosis and recycling of G protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:276–287. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRANE A., MALKHANDI J., MERCY L., KEEN M. The role of protein kinase A and protein kinase C in prostanoid IP receptor desensitization in NG108-15 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1206:203–207. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)90209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAURENZA A., MCHUGH SUTKOWSKI E., SEAMON K.B. Forskolin: a specific stimulator of adenylyl cyclase or a diterpene with multiple sites of action. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1989;10:442–447. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(89)80008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE N.H., MALEK R.L. Nerve growth factor regulation of m4 muscarinic receptor mRNA stability but not gene transcription requires mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:22317–22325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE N.H., WEINSTOCK K.G., KIRKNESS E.F., EARLE-HUGHES J.A., FULDNER R.A., MARMARAS S., GLODEK A., GOCAYNE J.D., FRASER C.M., VENTER J.C. Comparative expressed-sequence-tag analysis of differential gene expression profiles in PC-12 cells before and after nerve growth factor treatment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:8303–8307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVINE J.D., FIELDS H.L., BASBAUM A.I. Peptides and the primary afferent nociceptor. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:2273–2286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02273.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDSAY R.M. Nerve growth factors (NGF, BDNF) enhance axonal regeneration but are not required for survival of adult sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:2394–2405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-07-02394.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDSAY R.M., LOCKETT C., STERNBERG J., WINTER J. Neuropeptide expression in cultures of adult sensory neurones: modulation of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide levels by nerve growth factor. Neuroscience. 1989;33:53–65. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90310-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUMURA K., WATANABE Y., ONOE H., WATANABE Y. Prostacyclin receptor in the brain and central terminals of the primary sensory neurons: an autoradiographic study using a stable prostacyclin analogue [3H]iloprost. Neuroscience. 1995;65:493–503. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00505-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEHL M., BIDMON H.-J., HILBIG H., ZILLES K., DRINGEN R., ULLRICH V. Prostacyclin synthase is localized in rat, bovine and human neuronal brain cells. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;271:187–190. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00558-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURATA T., USHIKUBI F., MATSUOKA T., HIRATA M., YAMASAKI A., SUGIMOTO Y., ICHIKAWA A., AZE Y., TANAKA T., YOSHIDA N., UENO A., OH-ISHI S., NARUMIYA S. Altered pain perception and inflammatory response in mice lacking prostacyclin receptor. Nature. 1997;388:678–682. doi: 10.1038/41780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAMBA T., OIDA H., SUGIMOTO Y., KAKIZUKA A., NEGISHI M., ICHIKAWA A., NARUMIYA S. cDNA cloning of a mouse prostacyclin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:9986–9992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NARUMIYA S., SUGIMOTO Y., USHIKUBI F. Prostanoid receptors: structure, properties, and functions. Physiol. Rev. 1999;79:1193–1226. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHOLAS R.S., WINTER J., WREN P., BERGMANN R., WOOLF C.J. Peripheral inflammation increases the capsaicin sensitivity of dorsal root ganglion neurons in a nerve growth factor-dependent manner. Neuroscience. 1999;91:1425–1433. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00706-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIE Z., MEI Y., MALEK R.L., MARCUZZI A., LEE N.H., RAMKUMAR V. A role of p75 in NGF-mediated down-regulation of the A2A adenosine receptors in PC12 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:947–954. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.5.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHIGAKI N., NEGISHI M., ICHIKAWA A. Two Gs-coupled prostaglandin E receptor subtypes, EP2 and EP4, differ in desensitization and sensitivity to the metabolic inactivation of the agonist. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;50:1031–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NUMAGUCHI Y., HARADA M., OSANAI H., HAYASHI K., TOKI Y., OKUMURA K., ITO T., HAYAKAWA T. Altered gene expression of prostacyclin synthase and prostacyclin receptor in the thoracic aorta of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999;41:682–688. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OIDA H., NAMBA T., SUGIMOTO Y., USHIKUBI F., OHISHI H., ICHIKAWA A., NARUMIYA S. In situ hybridization studies of prostacyclin receptor mRNA expression in various mouse organs. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:2828–2837. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORTMANN R. Effect of PGI2 and stable endoperoxide analogues on cyclic nucleotide levels in clonal cell lines of CNS origin. FEBS Lett. 1978;90:348–352. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80402-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATRIZIO M., COLUCCI M., LEVI G. Protein kinase C activation reduces microglial cyclic AMP response to prostaglandin E-2 by interfering with EP2 receptors. J. Neurochem. 2000;74:400–405. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETERSEN M., SEGOND VON BANCHET G., HEPPELMANN B., KOLTZENBURG M. Nerve growth factor regulates the expression of bradykinin binding sites on adult sensory neurons via the neurotrophin receptor p75. Neuroscience. 1998;83:161–168. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00374-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROWLANDS D.K., WISE H. Regulation of prostacyclin receptors in rat dorsal root ganglia cells. Mediators of Inflammation. 1999;8:S107. [Google Scholar]

- SASAKI Y., USUI T., TANAKA I., NAKAGAWA O., SANDO T., TAKAHASHI T., NAMBA T., NARUMIYA S., NAKAO K. Cloning and expression of a cDNA for rat prostacyclin receptor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1224:601–605. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)90300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHRÖR K. Prostacyclin-dependent cyclic AMP formation in endothelial cells. Naunyn-Schmied. Arch. Pharmacol. 1993;347:101–104. doi: 10.1007/BF00168779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEREGI A., SCHOBERT A., HERTTING G. The stable prostacyclin-analogue, iloprost, unlike prostanoids and leukotrienes, potently stimulates cyclic adenosine monophosphate synthesis of primary astroglial cell cultures. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1988;40:437–438. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1988.tb06311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH J.A.M., AMAGASU S.M., EGLEN R.M., HUNTER J.C., BLEY K.R. Characterization of prostanoid receptor-evoked responses in rat sensory neurones. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;124:513–523. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMYTH E.M., HONG LI W., FITZGERALD G.A. Phosphorylation of the prostacyclin receptor during homologous desensitization. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:23258–23266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMYTH E.M., NESTOR P.V., FITZGERALD G.A. Agonist-dependent phosphorylation of an epitope-tagged human prostacyclin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:33698–33704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNIDER W.D., WRIGHT D.E. Neurotrophins cause a new sensation. Neuron. 1996;16:229–232. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOUTHALL M.D., VASKO M.R. Prostaglandin E2-mediated sensitization of rat sensory neurons is not altered by nerve growth factor. Neurosci. Lett. 2000;287:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANG W.-J., HURLEY J.H. Catalytic mechanism and regulation of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;54:231–240. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UENO A., NARABA H., IKEDA Y., USHIKUBI F., MURATA T., NARUMIYA S., OH-ISHI S. Intrinsic prostacyclin contributes to exudation induced by bradykinin or carrageenin: a study on the paw edema induced in IP-receptor-deficient mice. Life Sci. 2000;66:PL155–PL160. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UENO S., TSUDA M., IWANAGA T., INOUE K. Cell type-specific ATP-activated responses in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:429–436. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERITY A.N., WYATT T.L., LEE W., HAJOS B., BAECKER P.A., EGLEN R.M., JOHNSON R.M. Differential regulation of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) expression in human neuroblastoma and glioblastoma cell lines. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;55:187–197. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990115)55:2<187::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG J., YAMAMOTO K., SUGIMOTO Y., ICHIKAWA A., YAMAMOTO S. Induction of prostaglandin I2 receptor by tumor necrosis factor α in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1441:69–76. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIMALAWANSA S.J. Isolation, purification, and biochemical characterization of calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1992;650:70–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb22758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WISE H., JONES R.L. Prostacyclin and Its Receptors. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2000. pp. 1–310. [Google Scholar]

- ZUCKER T.-P., BÖNISCH D., HASSE A., GROSSER T., WEBER A.-A., SCHRÖR K. Tolerance development to antimitogenic actions of prostacyclin but not of prostaglandin E1 in coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;345:213–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]