Abstract

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are anti-hypertensive drugs that are usually considered to act mainly as vasodilators. We investigated the relation between the reduction of blood pressure evoked by two long-acting CCBs and their protective effect against cardiac and renal damage in salt-loaded stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRSP).

SHRSP were exposed to high dietary salt intake (1% NaCl in drinking solution) from 8 to 14 weeks of age, with or without amlodipine or lacidipine at three dosage regimens producing similar effects on blood pressure.

The lowest dosages of both drugs had non-significant effects on blood pressure but inhibited the paradoxical increases in plasma renin activity (PRA) and in renin mRNA in kidney that were found in salt-loaded SHRSP. The lowest dosage of lacidipine (but not of amlodipine) restored the physiological downregulation of renin production by high salt and reduced left ventricular hypertrophy and mRNA levels of atrial natriuretic factor and transforming growth factor-β1.

The intermediate dosages reduced blood pressure and PRA in a comparable manner, but cardiac hypertrophy was more reduced by lacidipine than by amlodipine.

Although the highest doses exhibited a further action on blood pressure, they had no additional effect on cardiac hypertrophy, and they increased PRA and kidney levels of renin mRNA even more than in the absence of drug treatment.

We conclude that reduction of blood pressure is not the sole mechanism involved in the prevention of cardiac remodelling by CCBs, and that protection against kidney damage and excessive renin production by low and intermediate dosages of these drugs contributes to their beneficial cardiovascular effects.

Keywords: Calcium channel blockers; calcium antagonists; hypertension; hypertrophy, left ventricular; renin-angiotensin system; transforming growth factor-β1

Introduction

Calcium antagonists, also termed calcium channel blockers (CCBs), are widely used for the management of essential hypertension, a disease complicated by cardiac hypertrophy and by other abnormalities (Susic et al., 1999). The therapeutic action of CCBs is usually attributed to arterial vasodilatation and to the subsequent lowering of blood pressure, which reduces cardiac load and the mechanical stress on the vessel wall (Godfraind, 1994). It has been shown that CCBs reduce cardiac fibrosis in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) (Campbell et al., 1993; Susic et al., 1999), prevent renal fibrosis (Kazda et al., 1987; Epstein, 1998) and reduce collagen deposition in the extracellular matrix formed by cultured human fibroblasts (Roth et al., 1996). Salt-loaded stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRSP), a good model of human malignant hypertension, develop cardiac hypertrophy associated with the re-expression of fetal genes before stroke and death (Kyselovic et al., 1998). The cytokine transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), which appears to play a pivotal role in promoting tissue fibrosis (Border & Noble, 1998), is also overexpressed (Kyselovic et al., 1998). A high dietary salt intake amplifies the pathology and accelerates the onset of end-organ tissue damage in SHRSP (Volpe et al., 1990; Griffin et al., 2001).

This study investigates the action of two long acting CCBs, amlodipine and lacidipine (Zannad et al., 1996), which have both been shown to reduce blood pressure and cardiac hypertrophy in SHRSP (Kim et al., 1996; Kyselovic et al., 1998). Because angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonists may reduce hypertension-related end-organ damage even at dosages inefficient on blood pressure (Stier et al., 1989; Kim et al., 1995), we tested the hypothesis that the prevention of organ alterations by CCBs could be partly independent of the reduction of blood pressure. Therefore we compared the actions of amlodipine and lacidipine at dosage regimens equivalent on systolic blood pressure (SBP) in SHRSP exposed to salt load. We assessed the tissue protective effect of CCBs by measuring left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy and the associated gene reprogramming and upregulation. Because we showed that lacidipine suppresses the paradoxical increase of plasma renin activity (PRA) in SHRSP exposed to salt load (Krenek et al., 2001), we also examined PRA and the abundance of renin and TGF-β1 mRNAs in kidney of SHRSP exposed to salt-load and treated with either amlodipine or lacidipine.

Methods

Experimental animals and tissue collection

All procedures followed were in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal research. Male, 8-week-old SHRSP (Iffa Credo, L'arbresle, France) were divided at random into eight groups (n=12). One group (W) was maintained on water and the other groups were given 1% NaCl as drinking solution (Kyselovic et al., 1998). Among salt-loaded groups, a control group (S) received ordinary chow, while the others received the same chow supplemented with either lacidipine (for a daily mean intake of 0.3, 1 or 3 mg kg−1; termed L0.3, L1 and L3, respectively) or amlodipine (for a daily mean intake of 1.5, 5 or 15 mg kg−1; termed A1.5, A5 and A15, respectively). Furthermore, additional experiments were performed with rats receiving only water with or without lacidipine 0.3 or 1 mg kg−1. SBP was measured by the tail-cuff method. At the age of 14 weeks, rats were killed by decapitation and blood was collected. Plasma was stored at −20°C for later analysis of PRA, according to a standard procedure (Medix Biochemica, Kauniainen, Finland). Heart and kidneys were removed, left ventricles were dissected out and organs were weighed and rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Oligonucleotide and cDNA probes

We used a γ-32P-ATP labelled synthetic oligonucleotide probe complementary to the unique 3′ untranslated region of skeletal α-actin mRNA, and γ-32P-dCTP labelled cDNA probes for TGF-β1, collagen I and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNA (Kyselovic et al., 1998). The probe for atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) was a 32P-labelled 460 bp cDNA fragment, prepared by reverse transcription/polymerase chain reaction using specific primers, corresponding to bases 69 to 529 of rat ANF mRNA. The sequence of the primers (Shin et al., 1998) was (5′- to 3′-): ATG GGC TCC TTC TCC ATC ACC (sense) and TGT TAT CTT CGG TAC CG (antisense).

Isolation of messenger RNA and Northern blot analysis

They were performed as previously described (Kyselovic et al., 1998). For all mRNA species, amounts were expressed relatively to that of GAPDH mRNA, which was taken as internal reference, to correct for differences in RNA loading and/or transfer. Finally, the ratios for untreated SHRSP (W) and drug-treated salt-loaded SHRSP were normalized with respect to control salt-loaded SHRSP (S) mRNA samples which had been processed simultaneously.

Drugs

Lacidipine was provided by Glaxo-Wellcome (Verona, Italy). Amlodipine was provided by Pfizer-Belgium.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean±s.e.mean. Differences between groups were evaluated by one-way ANOVA using the PRISM program; P values <0.05 were considered significant. Unless otherwise stated, the various groups of rats were compared to the S group according to Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons, n being the number of rats.

Results

Biometric data

Body weight at 14 weeks of age did not differ significantly between salt-loaded and control SHRSP (body weight, g: W, 273±3.5; S, 266±7.1 (n=12 in each group)). Salt loading increased SBP (mm Hg: W, 228±5.6; S, 251±6.4 (P<0.05)) and, more markedly, relative LV mass (mg g−1 body weight: W, 2.91±0.02; S, 3.35±0.09 (P<0.001)). Drug treatment had no significant effect on the body weight of salt-loaded SHRSP (not shown). Figure 1 illustrates the relation between SBP and the LV relative mass in rats exposed to salt with or without CCB treatment. At each of the three doses utilized, lacidipine and amlodipine reduced SBP in a comparable manner, but this reduction was not statistically significant with the lowest dose (L0.3 and A1.5). With the exception of amlodipine 1.5 mg kg−1 (A1.5), each drug treatment evoked a significant reduction of LV mass (P<0.001) and the values attained were not significantly different from the LV mass in non-salt-loaded SHRSP (2.91±0.02 mg g−1 body weight, not shown in Figure 1). However, for a similar level of SBP, the LV mass was lower in the group treated with lacidipine than in the group treated with amlodipine (P<0.05). Increasing the dosage from 1 to 3 mg kg−1 for lacidipine, or from 5 to 15 mg kg−1 for amlodipine, did not decrease LV mass further despite a consistent reduction in SBP.

Figure 1.

Relation between relative left ventricular mass and systolic blood pressure in salt-loaded SHRSP. S, salt-loaded SHRSP; A1.5, amlodipine 1.5 mg kg−1; A5, amlodipine 5 mg kg−1; A15, amlodipine 15 mg kg−1; L0.3, lacidipine 0.3 mg kg−1; L1, lacidipine 1 mg kg−1; L3, lacidipine 3 mg kg−1.

Markers of hypertrophy and fibrosis in left ventricle

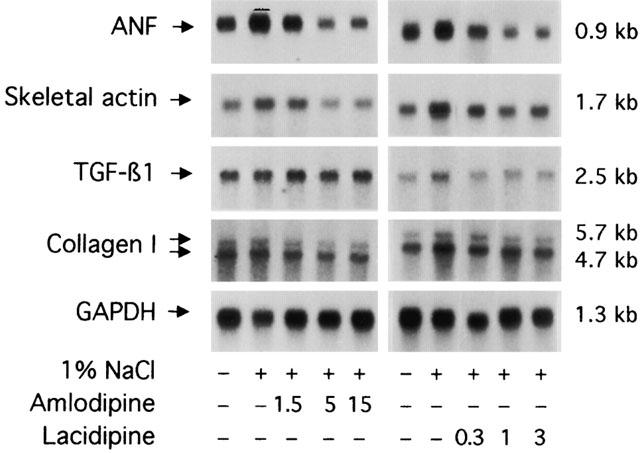

The mRNA levels of cardiac genes associated with hypertrophy and remodelling (ANF, skeletal α-actin, TGF-β1 and collagen type I) were estimated by Northern blot analysis on LV samples taken at random from the various groups (n=5 or higher). As reported by Kim et al. (1995), these genes are significantly overexpressed in SHRSP compared with WKY. We have previously shown that lacidipine treatment decreases the ventricular expression of several genes in salt-loaded SHRSP (Kyselovic et al., 1998). The present data (Figures 2 and 3) confirm our former findings and extend them to the ANF gene. Furthermore, Figure 3 illustrates that the degree of reduction of gene expression and its level of statistical significance varied with the gene and the dose of the CCB. When comparing the two drugs at dosages that were equi-effective on SBP reduction, it appears that lacidipine evoked a higher degree of inhibition of gene overexpression than amlodipine. Significant differences between the two drugs were observed for ANF and TGF-β1 (P<0.05), but not for skeletal α-actin and collagen type I.

Figure 2.

Northern analysis of mRNA levels in left ventricular tissue: typical autoradiograms. Blots were sequentially hybridized with 32P-labelled probes for collagen type I, TGF-β1, skeletal α-actin, ANF and GAPDH mRNA, as described in Methods. One per cent NaCl refers to salt given (+) or not given (−) in drinking water (see Methods). Drug doses are expressed in mg kg−1 day−1. mRNA size is given on the right.

Figure 3.

Northern analysis of mRNA levels in left ventricular tissue. Data were corrected for GAPDH mRNA levels and normalized with respect to salt-loaded SHRSP (S). W, control SHRSP; A1.5, amlodipine 1.5 mg kg−1; A5, amlodipine 5 mg kg−1; A15, amlodipine 15 mg kg−1; L0.3, lacidipine 0.3 mg kg−1; L1, lacidipine 1 mg kg−1; L3, lacidipine 3 mg kg−1. Data are mean±s.e.mean of at least five rats (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001).

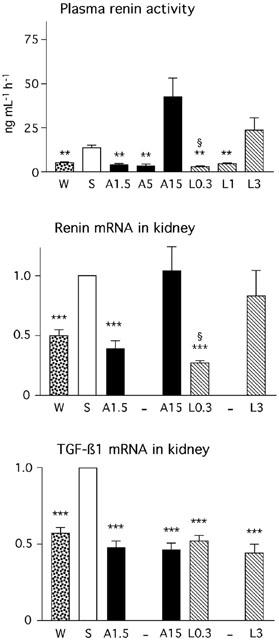

Plasma renin activity

Confirming previous observations (Krenek et al., 2001), PRA increased significantly in salt-loaded SHRSP (Figure 4). When salt-loaded SHRSP were treated with low and intermediate dosages of amlodipine (A1.5 and A5) or lacidipine (L0.3 and L1), PRA remained significantly lower than in the absence of drug treatment (P<0.01). In contrast, with the highest dosages of both amlodipine (A15) and lacidipine (L3) we observed an increase in PRA compared with the S group, which, however, reached statistical significance for the A15 group only (P<0.05).

Figure 4.

Plasma renin activity and Northern analysis of mRNA levels in kidney tissue. mRNA levels were corrected for GAPDH mRNA levels and normalized with respect to salt-loaded SHRSP (S). W, control SHRSP; A1.5, amlodipine 1.5 mg kg−1; A5, amlodipine 5 mg kg−1; A15, amlodipine 15 mg kg−1; L0.3, lacidipine 0.3 mg kg−1; L1, lacidipine 1 mg kg−1; L3, lacidipine 3 mg kg−1. Data are mean±s.e.mean of at least five rats (**P<0.01 vs S; ***P<0.001 vs S; §P<0.05 vs W).

In rats treated with the lowest dose of lacidipine (L0.3), PRA was significantly less than in untreated rats not exposed to high salt (W): 1.92±0.35 ng ml−1 h−1 vs 5.93±1.52 (n=7, P<0.05). In view of these results, a control experiment was conducted with SHRSP with or without lacidipine treatment (0.3 and 1 mg kg−1), in the absence of salt loading (n=7 in each group). PRA values were respectively equal to 5.24±0.52, 6.16±0.90 and 8.01±1.16 ng ml−1 h−1 (P>0.05). SBP values were also similar in those three groups (data not shown). Thus, in salt-loaded SHRSP treated with lacidipine 0.3 mg kg−1, but not in those treated with amlodipine 1.5 mg kg−1, the inhibitory effect of high salt diet on renin secretion, as observed in normotensive rats, was apparently recovered.

Gene expression in kidney

Figures 4 and 5 show that the abundance of renin mRNA in the kidney was increased in salt-loaded SHRSP (P<0.001) and that this increase was prevented by the lowest dose of amlodipine (A1.5) and lacidipine (L0.3) (P<0.001) but not by the highest dose (A15 and L3). Interestingly, renin transcripts were significantly lower in L0.3 group than in W group (P<0.01), an observation consistent with PRA values. On the other hand, the abundance of the mRNA of TGF-β1 was also significantly increased in salt-loaded SHRSP but this increase was similarly blocked by the lowest and highest dosages of the two CCBs.

Figure 5.

Northern analysis of mRNA levels in kidney tissue: typical autoradiograms. Blots were sequentially hybridized with 32P-labelled probes for renin, TGF-β1 and GAPDH mRNA, as described in Methods. One per cent NaCl refers to salt given (+) or not given (−) in drinking water (see Methods). Drug doses are expressed in mg kg−1 day−1. mRNA size is given on the right.

Discussion

As reported by Kim et al. (1996), amlodipine reduces cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac hypertrophy-related gene reprogramming in SHRSP. We have previously found that lacidipine, at dosages that are devoid of myocardial effects in normotensive WKY rats (Feron et al., 1996), counteracts cardiac hypertrophy and the upregulation of genes associated with hypertrophy and fibrosis in salt-loaded SHRSP (Kyselovic et al., 1998). To gain further insight into the mechanism(s) of the cardio-protective action of those two long-acting CCBs, we compared the dose-dependence of their effect on SBP and on cardiac remodelling in salt-loaded SHRSP. For a similar effect on SBP, the reduction of the relative LV mass and of the LV levels of ANF and TGF-β1 mRNA was significantly more important with lacidipine than with amlodipine. This comparison indicates that the beneficial effect of CCBs on cardiac remodelling could not be simply related to the reduction of SBP.

The renin angiotensin system (RAS) plays a major role in both cardiovascular hypertrophy and gene reprogramming induced by hypertension (Kim & Iwao, 2000). Angiotensin II is a potent stimulus for cellular hypertrophy and gene reprogramming in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes and for hyperplasia and upregulation of fibrosis-associated genes in cardiac fibroblasts. Angiotensin II may act partly by inducing the production of other factors such as endothelin-1 (Ito et al., 1993) and TGF-β1 (Sharma et al., 1994). In agreement with previous reports (Shibota et al., 1979; Volpe et al., 1990), salt-loaded SHRSP showed a paradoxical increase in PRA. As shown by Müller et al. (1998) in Langendorff preparations, circulating renin can be taken up by the heart and induce local generation of angiotensin II. Elevated levels of circulating renin in salt-loaded SHRSP could thus increase LV concentrations of renin, thereby amplifying the activation of cardiac RAS induced by pressure overload (Dostal & Baker, 1999). Therefore, prevention of PRA increase in salt-loaded SHRSP treated with low dosages of lacidipine or amlodipine could contribute to their cardio-protective effects.

As shown for the first time in this study, the paradoxical PRA increase in salt-loaded SHRSP is accompanied by elevated renal levels of renin mRNA, confirming that the physiological downregulation by salt of renin production by the kidney is lost in those hypertensive rats. Activation of renin production is probably secondary to renal damage that is accelerated by the high dietary salt intake in this strain, as previously suggested by others (Matsunaga et al., 1975; Shibota et al., 1979). The salt-induced renal damage in SHRSP, as measured by urinary protein excretion or lesions of malignant nephrosclerosis, is disproportionate to the corresponding increase in absolute blood pressure (Griffin et al., 2001). This nephropathy has been shown to be partly prevented by CCBs, e.g. nimodipine, lacidipine and amlodipine at dosages that do not evoke a marked reduction of blood pressure (Kazda et al., 1987; Suzuki et al., 1993; Cristofori et al., 1994). The nephroprotective effect of lacidipine, at doses identical to those that we used in this study, has been demonstrated by both morphological and functional (urinary protein excretion) methods (Cristofori et al., 1994) and is consistent with our observation that the increase in kidney levels of TGF-β1 mRNA in salt-loaded SHRSP was prevented by CCBs; indeed, TGF-β1 is considered as playing a key role in the glomerulosclerosis associated with hypertensive renal disease (Nakamura et al., 1996). Therefore, prevention by low-dose CCBs of the paradoxical PRA increase in salt-loaded SHRSP is likely to be related to a nephroprotective action that is partly independent of the effect on blood pressure. It has been reported that nifedipine and dihydropyridine compounds that are devoid of calcium channel blocking properties inhibit protein kinase C in endothelial cells and protect them against ischaemia-induced permeability (Hempel et al., 1999). This action could contribute to the nephroprotective effect of CCBs in view of the potential role of protein kinase C in progressive renal disease (Gilbert et al., 2001).

The modulation of PRA and renin production by CCBs followed a biphasic pattern, characterized by a decrease at low dosages and an increase at the highest dosage used. By contrast, the elevation of TGF-β1 transcripts in the kidney of salt-loaded SHRSP was similarly reduced by low and high dosages of CCBs, suggesting that the increase in PRA observed with the highest dosages was not related to kidney damage but to another mechanism. Increased renin secretion and renin gene expression in the kidney has been reported by Schricker et al. (1996) in Sprague-Dawley rats exposed to amlodipine 15 mg kg−1 day−1 (but not at the dose of 5 mg kg−1 day−1). This effect occurred after 1 day of treatment and persisted for at least 4 days. It is known that the renal renin system is modulated by local factors such as prostaglandins and nitric oxide (NO) and that the overall effect of NO on renin production in vivo is stimulatory (Kurtz & Wagner, 1998). On the other hand, it has been shown that amlodipine (Zhang & Hintze, 1998) and lacidipine (Crespi et al., 2001), albeit at relatively high concentrations, increase NO release from isolated blood vessels, an action that may be related to stimulation of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) gene expression as shown both in cultured endothelial cells (Ding & Vaziri, 1998) and in SHRSP in vivo (Krenek et al., 2001). It may be hypothetized that such a mechanism could contribute to an enhanced production of renin in the kidneys of SHRSP exposed to high dosages of CCBs. Alternatively, enhanced production of renin might follow sympathetic activation, which has been described after chronic amlodipine therapy in essential hypertensive patients (de champlain et al., 1998; Fogari et al., 2000). However, such an activation was not observed with lacidipine (Fogari et al., 2000), which, at the dose of 3 mg kg−1, was able to increase PRA in salt-loaded SHRSP.

As discussed above, low-dose CCBs appear to counteract cardiac remodelling in salt-loaded SHRSP mainly by protecting the kidney, thereby preventing PRA elevation and, presumably, reducing angiotensin II generation within the heart. However, at dosages that evoke a significant reduction of blood pressure, reduction of haemodynamic overload by CCBs might play a greater role in cardioprotection. The increased PRA observed with high dosages of CCBs might counterbalance the benefit related to reduction of wall stress, in such a way that higher reduction of SBP did not cause further decrease in LV mass (see Figure 1). Furthermore, despite similar SBP and PRA values, lacidipine was significantly more effective than amlodipine in reducing LV mass. This suggests that additional drug effects on the heart could be involved in the prevention of cardiac remodelling and gene reprogramming. Recently, Müller et al. (2000) have shown that inhibition of the transcription factor NF-κB by the antioxidant pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate ameliorates angiotensin II-induced damage (including cardiac hypertrophy) in double-transgenic rats harbouring both human renin and angiotensinogen genes. As reported by Cominacini et al. (1997), lacidipine inhibits NF-κB activation induced by pro-oxidant signals in endothelial cells. We have shown that lacidipine and nifedipine exhibit antioxidant activity in vivo and that lacidipine and vitamin E are more effective than nifedipine in the prevention of apolipoprotein B oxidation (Napoli et al., 1999). Amlodipine, in contrast to nifedipine, did not inhibit activation of NF-κB in a cell line transfected with an NF-κB reporter plasmid (Matsumori et al., 2000). This may be related to the lower antioxidant capacity of amlodipine compared to that of lacidipine and nifedipine (Ursini, 1997).

In conclusion, this study shows that the prevention of cardiac remodelling observed with long-acting CCBs in salt-loaded SHRSP is not entirely attributable to the reduction of haemodynamic overload. Inhibition of RAS activation is likely to be involved in the blood pressure-independent cardioprotective effects of CCBs. Additional tissue protection resulting from interaction with deleterious oxygen free radicals might account for selective differences between individual drugs.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Leonardy and M.C. Hamaide for skilful technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Communauté française de Belgique (Actions de recherche concertée n° 96/01 – 199), the Belgian Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (F.R.S.M. n° 3.4585.00) and Glaxo Wellcome.

Abbreviations

- A1.5

salt-loaded SHRSP treated with amlodipine 1.5 mg.kg−1.day−1

- A5

salt-loaded SHRSP treated with amlodipine 5 mg.kg−1.day−1

- A15

salt-loaded SHRSP treated with amlodipine 15 mg.kg−1.day−1

- ACE

angiotensin converting enzyme

- ANF

atrial natriuretic factor

- CCB

calcium channel blocker

- eNOS

endothelial NO synthase

- L0.3

salt-loaded SHRSP treated with lacidipine 0.3 mg.kg−1.day−1

- L1

salt-loaded SHRSP treated with lacidipine 1 mg.kg−1.day−1

- L3

salt-loaded SHRSP treated with lacidipine 3 mg.kg−1.day−1

- LV

left ventricular

- NO

nitric oxide

- PRA

plasma renin activity

- RAS

renin angiotensin system

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- S

salt-loaded SHRSP

- SHR

spontaneously hypertensive rat

- SHRSP

stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rat

- TGF-β1

transforming growth factor β1

- W

control SHRSP

References

- BORDER W.A., NOBLE N.A. Interactions of transforming growth factor-beta and angiotensin II in renal fibrosis. Hypertension. 1998;31:181–188. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMPBELL S.E., TUREK Z., RAKUSAN K., KAZDA S. Cardiac structural remodelling after treatment of spontaneously hypertensive rats with nifedipine or nisoldipine. Cardiovasc. Res. 1993;27:1350–1358. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.7.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COMINACINI L., GARBIN U., FRATTA PASINI A., PAULON T., DAVOLI A., CAMPAGNOLA M., MARCHI E., PASTORINO A.M., GAVIRAGHI G., LO CASCIO V. Lacidipine inhibits the activation of the transcription factor NF-kappaB and the expression of adhesion molecules induced by pro-oxidant signals on endothelial cells. J. Hypertens. 1997;15:1633–1640. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715120-00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRESPI F., VECCHIATO E., LAZZARINI C., GAVIRAGHI G. Electrochemical evidence that lacidipine stimulates release of nitrogen monoxide in rat aorta. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;298:171–174. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01756-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRISTOFORI P., MICHELI D., TERRON A., GAVIRAGHI G. Lacidipine: experimental evidence of vasculoprotective properties. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1994;23:S90–S93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE CHAMPLAIN J., KARAS M., NGUYEN P., CARTIER P., WISTAFF R., TOAL C.B., NADEAU R., LAROCHELLE P. Different effects of nifedipine and amlodipine on circulating catecholamine levels in essential hypertensive patients. J. Hypertens. 1998;16:1357–1369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DING Y., VAZIRI N.D. Calcium channel blockade enhances nitric oxide synthase expression by cultured endothelial cells. Hypertension. 1998;32:718–723. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.4.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOSTAL D.E., BAKER K.M. The cardiac renin-angiotensin system: conceptual, or a regulator of cardiac function. Circ. Res. 1999;85:643–650. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.7.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPSTEIN M. Calcium antagonists and renal protection: emerging perspectives. J. Hypertens. 1998;16:S17–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERON O., SALOMONE S., GODFRAIND T. Action of the calcium channel blocker lacidipine on cardiac hypertrophy and endothelin-1 gene expression in stroke-prone hypertensive rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:659–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15451.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOGARI R., ZOPPI A., CORRADI L., PRETI P., MALALAMANI G.D., MUGELLINI A. Effects of different dihydropyridine calcium antagonists on plasma norepinephrine in essential hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2000;18:1871–1875. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018120-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILBERT R.E., KELLY D.J., ATKINS R.C. Novel approaches to the treatment of progressive renal disease. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2001;1:183–189. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(01)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GODFRAIND T. Calcium antagonists and vasodilatation. Pharmacol. Ther. 1994;64:37–75. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIFFIN K.A., CHURCHILL P.C., PICKEN M., WEBB R.C., KURTZ T.W., BIDANI A.K. Differential salt-sensitivity in the pathogenesis of renal damage in SHR and stroke prone SHR. Am. J. Hypertens. 2001;14:311–320. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(00)01282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEMPEL A., LINDSCHAU C., MAASCH C., MAHN M., BYCHKOV R., NOLL T., LUFT F.C., HALLER H. Calcium antagonists ameliorate ischemia-induced endothelial cell permeability by inhibiting protein kinase C. Circulation. 1999;99:2523–2529. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.19.2523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO H., HIRATA Y., ADACHI S., TANAKA M., TSUJINO M., KOIKE A., NOGAMI A., MARUMO F., HIROE M. Endothelin-1 is an autocrine/paracrine factor in the mechanism of angiotensin II-induced hypertrophy in cultured rat cardiomyocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;92:398–403. doi: 10.1172/JCI116579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAZDA S., GRUNT M., HIRTH C., PREIS W., STASCH J.P. Calcium antagonism and protection of tissues from calcium damage. J. Hypertens. 1987;5:S37–S42. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198712004-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM S., IWAO H. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of angiotensin II-mediated cardiovascular and renal diseases. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000;52:11–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM S., OHTA K., HAMAGUCHI A., OMURA T., YUKIMURA T., MIURA K., INADA Y., ISHIMURA Y., CHATANI F., IWAO H. Angiotensin II type I receptor antagonist inhibits the gene expression of transforming growth factor-β1 and extracellular matrix in cardiac and vascular tissues of hypertensive rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;273:509–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM S., OHTA K., HAMAGUCHI A., YUKIMURA T., MIURA K., IWAO H. Effects of an AT1 receptor antagonist, an ACE inhibitor and a calcium channel antagonist on cardiac gene expressions in hypertensive rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:549–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRENEK P., SALOMONE S., KYSELOVIC J., WIBO M., MOREL N., GODFRAIND T. Lacidipine prevents endothelial dysfunction in salt-loaded stroke-prone hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2001;37:1124–1128. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.4.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KURTZ A., WAGNER C. Role of nitric oxide in the control of renin secretion. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:F849–F862. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.6.F849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KYSELOVIC J., MOREL N., WIBO M., GODFRAIND T. Prevention of salt-dependent cardiac remodeling and enhanced gene expression in stroke-prone hypertensive rats by the long-acting calcium channel blocker lacidipine. J. Hypertens. 1998;16:1515–1522. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816100-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUMORI A., NUNOKAWA Y., SASAYAMA S. Nifedipine inhibits activation of transcription factor NF-κB. Life Sci. 2000;67:2655–2661. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00849-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUNAGA M., YAMAMOTO J., HARA A., YAMORI Y., OGINO K. Plasma renin and hypertensive vascular complications: an observation in the stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rat. Jpn. Circ. J. 1975;39:1305–1311. doi: 10.1253/jcj.39.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MÜLLER D.N., DECHEND R., MERVAALA E.M., PARK J.K., SCHMIDT F., FIEBELER A., THEUER J., BREU V., GANTEN D., HALLER H., LUFT F.C. NF-κB inhibition ameliorates angiotensin II-induced inflammatory damage in rats. Hypertension. 2000;35:193–201. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MÜLLER D.N., FISCHLI W., CLOZEL J.P., HILGERS K.F., BOHLENDER J., MENARD J., BUSJAHN A., GANTEN D., LUFT F.C. Local angiotensin II generation in the rat heart: role of renin uptake. Circ. Res. 1998;82:13–20. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAMURA T., OBATA J., KUROYANAGI R., KIMURA H., IKEDA Y., TAKANO H., NAITO A., SATO T., YOSHIDA Y. Involvement of angiotensin II in glomerulosclerosis of stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Kidney Int. 1996;55:S109–S112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAPOLI C., SALOMONE S., GODFRAIND T., PALINSKI W., CAPUZZI D.M., PALUMBO G., D'ARMIENTO F.P., DONZELLI R., DE NIGRIS F., CAPIZZI R.L., MANCINI M., GONNELLA J.S., BIANCHI A. 1,4-Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers inhibit plasma and LDL oxidation and formation of oxidation-specific epitopes in the arterial wall and prolong survival in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Stroke. 1999;30:1907–1915. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.9.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROTH M., EICKELBERG O., KOHLER E., ERNE P., BLOCK L.H. Ca2+ channel blockers modulate metabolism of collagens within the extracellular matrix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:5478–5482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHRICKER K., HAMANN M., MACHER A., KRAMER B.K., KAISSLING B., KURTZ A. Effect of amlodipine on renin secretion and renin gene expression in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;119:744–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15735.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHARMA H.S., VAN HEUGTEN H.A., GOEDBLOED M.A., VERDOUW P.D., LAMERS J.M. Angiotensin II induced expression of transcription factors precedes increase in transforming growth factor-beta 1 mRNA in neonatal cardiac fibroblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;205:105–112. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIBOTA M., NAGAOKA A., SHINO A., FUJITA T. Renin-angiotensin system in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1979;236:H409–H416. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.3.H409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIN S.J., WEN J.D., CHEN I.H., LAI F.J., HSIEH M.C., HSIEH T.J., TAN M.S., TSAI J.H. Increased renal ANP synthesis, but decreased or unchanged cardiac ANP synthesis in water-deprived and salt-restricted rats. Kidney Int. 1998;54:1617–1625. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STIER C.T., JR, BENTER I.F., AHMAD S., ZUO H.L., SELIG N., ROETHEL S., LEVINE S., ITSKOVITZ H.D. Enalapril prevents stroke and kidney dysfunction in salt-loaded stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1989;13:115–121. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUSIC D., VARAGIC J., FROHLICH E.D. Pharmacologic agents on cardiovascular mass, coronary dynamics and collagen in aged spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Hypertens. 1999;17:1209–1215. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917080-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUZUKI M., YAMANAKA K., NABATA H., TACHIBANA M. Long term effects of amlodipine on organ damage, stroke and life span in stroke prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;228:269–274. doi: 10.1016/0926-6917(93)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- URSINI F. Tissue protection by lacidipine: insights from redox behavior. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1997;30:S28–S30. [Google Scholar]

- VOLPE M., CAMARGO M.J., MUELLER F.B., CAMPBELL W.G., JR, SEALEY J.E., PECKER M.S., SOSA R.E., LARAGH J.H. Relation of plasma renin to end organ damage and to protection of K+ feeding in stroke-prone hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1990;15:318–326. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.15.3.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZANNAD F., MATZINGER A., LARCHE J. Trough/peak ratios of once daily angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and calcium antagonists. Am. J. Hypertens. 1996;9:633–643. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(96)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG X., HINTZE T.H. Amlodipine releases nitric oxide from canine coronary microvessels: an unexpected mechanism of action of a calcium channel-blocking agent. Circulation. 1998;97:576–580. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.6.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]