Abstract

2-amino-4, 4α-dihydro-4α, 7-dimethyl-3H-phenoxazine-3-one (Phx) has been demonstrated to be an actinomycin D-like phenoxazine, and to display anti-tumour activity.

In this study, we report on the effect of Phx on B cell antigen receptor (BCR) and receptor-mediated signalling in DT40 B cells.

Treatment of B cells with Phx for 12 h inhibited BCR-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins.

B cells exposed to Phx exhibited down-regulation of surface IgM which is part of BCR. In contracts with actinomycin D, Phx rapidly reduced the expression of IgM without decreasing the expression of other signalling molecules.

Analysis with confocal microscopy demonstrated that Phx treatment reduced IgM expression both at the cell surface and inside the cell.

Treatment of B cells with Phx resulted in the reduction of IgM secretion. Since MG-132, a proteasomal inhibitor, restored IgM contents to the control levels, Phx has the specific effect of accelerating IgM degradation.

These results suggest that Phx down-regulates the expression of IgM and inhibits BCR-mediated signalling and IgM secretion. Phx may be useful as an immunosuppressive agent for therapeutic purposes.

Keywords: 2-amino-4,4α-dihydro-4α,7-dimethyl-3H-phenoxazine-3-one; B cells; B cell receptor; immunoglobulin expression

Introduction

Actinomycin D is known to inhibit the activity of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase to intercalate DNA, and has strong anti-tumour activity (Goldberg & Friedman, 1971; Wadkins et al., 1996). Tomoda et al. found that 2-amino-4, 4α-dihydro-4α, 7-dimethyl-3H-phenoxazine-3-one (Phx) was produced in vitro by the reactions of 2-amino-5-methylphenol with human or bovine hemoglobin (Tomoda et al., 1986; 1991; 1992; Ishida et al., 1996). Phx is a novel phenoxazine derivative and has the three rings structure, in common with actinomycin D as phenoxazinone. It has been reported that chemically synthesized phenoxazines show little solubility in water and have no anti-tumour activity (Motohashi et al., 1991). In contrast, Phx is soluble in water (1.2 mM at 37°C) and exerts anti-tumour effects in vitro on a variety of cultured cell lines such as human epidermoid carcinoma cells, human lung cancer cell lines, and human leukemia cell lines (Ishida et al., 1996; Abe et al., 2001; Shimamoto et al., 2001). Moreover, it has been shown that administration of Phx to mice transplanted with Meth A carcinoma cells or leukemia cells caused extensive suppression of the growth of transplants (Mori et al., 2000; Shimamoto et al., 2001). Unlike actinomycin D, Phx has no DNA intercalating activity (Ishida et al., 1996). Phx can be expected to become available for the treatment of cancer in the future; however, the mechanism of action of Phx has remained unclear.

The chemical structure of Phx is also similar to that of 1,3,8-trihydroxy-6-methylanthraquinone (emodin). Emodin exhibits immunosuppressive and vasorelaxant activities (Huang et al., 1991). It has been reported that emodin suppresses the proliferative responses of mononuclear cells to phytohemagglutinin (PHA) and mixed lymphocyte reaction (Huang et al., 1992). Recently, an interesting report has shown that Phx inhibits proliferation of PHA stimulated mononuclear cells, whereas it accelerates the incorporation of thymidine into anti-IgM-activated mononuclear cells (Akazawa et al., 2002). These findings prompted us to investigate if Phx has an immunosuppressive effect.

In this study, we have investigated the effect of Phx on B cell receptor (BCR) signalling and immunoglobulin expression. Phx markedly reduced the IgM expression and secretion of IgM in B cells, resulting in the inhibition of BCR-mediated signalling. It is expected that Phx may become a therapeutic agent that normalizes the abnormal enhancement of immunoglobulin production.

Methods

Materials

The RPMI 1640 medium was purchased from ICN Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Costa Mesa, CA, U.S.A.). Foetal calf serum, Cy3-conjugated anti-goat IgG and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Trypan blue was from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, (Osaka, Japan). The monoclonal antibody M4, an anti-chicken IgM, was used for stimulation of BCR in DT40 cells (Chen et al., 1982). Phx was synthesized and purified as described previously (Tomoda et al., 2001). Anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (4G10) and anti-Shc antibody were obtained from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY, U.S.A.). Immunoblotting and confocal microscopy of IgM were performed using the goat anti-chicken IgM-μ chain specific antibody, which was from Bethyl Laboratories, Inc. (Montgomery, TX, U.S.A.). Anti-Syk polyclonal antibodies (N-19 and C-20) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.). Anti-α-tubulin antibody was from Amersham (Piscataway, NJ, U.S.A.). Anti-trans-Golgi Network38 antibody was from Oncogene Research Products (Boston, MA, U.S.A.). MG-132 was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.).

Cell culture

DT40 chicken B cells were kindly provided by Dr Kurosaki (Kansai Medical University, Moriguchi, Japan). Establishment of Syk-deficient DT40 cells (Syk−) and Syk− cells expressing porcine Syk (Syk/Syk−) were performed as described previously (Takata et al., 1994). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v v−1) foetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 kanamycin in a humidified 95% air/5% CO2 atmosphere.

Determination of cell proliferation and cell survival

Cells were seeded at 106 cells ml−1 and were cultured for 24 h in the presence of various concentrations of Phx. Cell numbers were determined using a Coulter counter (Coulter Multisizer II, Coulter Corp., Miami, FL, U.S.A.) and a Burker–Türk counting chamber (Erma, Tokyo, Japan). Cell viability was confirmed by the trypan blue dye exclusion method.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Cells (107 cells per sample) were collected by centrifugation at 400×g for 5 min and washed with phosphate-buffered saline. Washed cells were solubilized in 1 ml ice-cold lysis buffer ((mM) Tris-HCl 50, pH 7.4, NaCl 150, EDTA 5, 1% NP-40, NaF 10, sodium pyrophosphate 10, Na3VO4 1, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride 2, 10 μg ml−1 leupeptin and 10 μg ml−1 aprotinin). Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 12,000×g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were incubated sequentially (1 h for each incubation) with antibodies and proteinA-Sepharose 4FF (Sigma) at 4°C, and immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred electrophoretically to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, U.S.A.). Blots were probed with the indicated antibodies and immunoreactive proteins were visualized by the Enhanced Chemiluminescence detection system (Parkin Elmer Life Science, Boston, MA, U.S.A.). Densitometric analyses of blots were performed using the NIH Image software version 1.62.

Immunofluorescence study

Cells (106 cells ml−1) were treated with or without 50 μM Phx for 12 h. Cells were attached to coverslips pre-coated with poly-L-lysine (100 μg ml−1; Sigma) for 10 min at room temperature. Adherent cells were stimulated with or without M4 (4 μg ml−1) in regular culture medium for 5 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with goat anti-chicken IgM plus Cy3-conjugated anti-goat IgG antibodies. Double immunofluorescence stainings were performed using mouse anti-TGN38 and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibodies. Cells undergoing staining of intracellular proteins were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and then immunostained. Laser scanning confocal microscopy was performed using a Nikon Optiphot microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and a Bio-Rad MRC-1024 confocal system (Bio-Rad, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Phx inhibits the proliferation of DT40 B cells

It has previously been reported that Phx inhibits the proliferation of human epidermoid carcinoma cells, Meth A carcinoma cells, human lung cancer cell lines, and human leukemia cell lines (Ishida et al., 1996; Mori et al., 2000; Abe et al., 2001; Shimamoto et al., 2001). So we first examined the effect of Phx on the proliferation of DT40 chicken B cells. DT40 cells were maintained in their normal medium with various doses of Phx. As shown in Figure 1, the increase in cell number was almost identical at all dose levels during the first 12 h of treatment. However, exposure to Phx for an extra 12 h (24 h total) resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation. Treatment with 50 μM Phx for 12 h kept the percentage of nonviable cells at less than 2%, the same as controls. Even in the presence of 100 μM Phx more than 95% of the cells were viable as determined by trypan blue dye exclusion.

Figure 1.

Effect of Phx on cell growth in DT40 cells. Cells were seeded at 106 cells ml−1 and were cultured for 24 h in the presence of the indicated concentrations of Phx. Cell numbers were counted with a Coulter counter.

Treatment of B cells with Phx inhibits BCR signalling and reduces the expression of IgM

It is clear that the BCR plays a central role in determining the fate of B cells. We studied the effect of Phx on intracellular signal transduction following BCR stimulation. One of the earliest events following BCR stimulation is the induction of tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins (Takata et al., 1994). DT40 cells pretreated with 50 μM Phx for a short period (30 min) were stimulated by an anti-IgM antibody (M4), and then the cell lysates were analysed by immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. As shown in Figure 2a, pretreatment with Phx for 30 min had no effect on tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins upon BCR stimulation. On the other hand, pre-treatment with 100 μM Phx for 12 h inhibited tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins in both unstimulated (−M4) and BCR-stimulated (+M4) cells (Figure 2b). In DT40 cells, total tyrosine phosphorylation requires activated Syk, which is downstream from BCR. The tyrosine phosphorylation of Syk and Shc following BCR stimulation (Sada et al., 2001) were inhibited by treatment with Phx for 12 h (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Effect of Phx on tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins following BCR stimulation. (a) Cells were pretreated with or without 50 μM Phx for 30 min and then were stimulated with anti-IgM antibody (M4, 4 μg ml−1) for the indicated periods. Cell lysates were subjected to anti-phosphotyrosine immunoblotting. (b) Cells were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of Phx for 12 h and then stimulated with M4 for 2 min. Cell lysates were subjected to anti-phosphotyrosine immunoblotting. (c) The same membrane as shown in (b) was stripped and re-probed with an anti-IgM, anti-Syk or anti-α-tubulin antibody. (d) DT40 wild type or porcine Syk expressing cells (Syk/Syk−) were pretreated with or without 100 μM Phx. Either unstimulated or M4-stimulated cell lysates were immunoprecipitated by anti-Shc antibody and immunoprecipitates were analysed by immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody and the membrane was re-probed with anti-Shc antibody using HRP-labelled Protein A (Sigma) as the second antibody. The mobility of p52Shc appears to overlap with the heavy chain of the precipitating antibody (H). Syk/Syk− DT40 cells were immunoprecipitated by anti-Syk antibody (C-20) and analysed by immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-Syk antibodies. The results from one representative experiment that was repeated three times are shown.

We further examined whether treatment with Phx for 12 h had an effect on the expression of signalling molecules. In DT40 cells, BCR is composed of heavy chains Igμ and light chains (Chen et al., 1982). Anti-IgM immunoblotting of the same membrane as shown in Figure 2b clearly showed reduced IgM expression in B cells pretreated with Phx for 12 h (Figure 2c). However, the expression of Syk and α-tubulin were not affected by Phx pretreatment of B cells (Figure 2c). These results suggest that treatment with Phx for 12 h inhibits BCR expression resulting in reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins following BCR stimulation.

The basic structure of Phx is similar to that of actinomycin D, which is known to intercalate DNA and inhibit RNA synthesis. We compared the effect of Phx with that of actinomycin D on IgM expression. As shown in Figure 3a, IgM expression after treatment of B cells with Phx started to decrease at 4 h and was drastically reduced by 12 h. The treatment with Phx for 12 h has no effect on the expression of Syk or α-tubulin. On the other hand, the effect of actinomycin D on the reduction of IgM expression appeared more slowly than that of Phx. The decrease in IgM expression by actinomycin D was small at 16 h and significant at 32 h (Figure 3b). Down-regulation of Syk protein expression followed a similar time course as IgM. We carried out the same experiment using cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, and obtained similar results (Figure 3c). Thus, unlike actinomycin D and cycloheximide, Phx rapidly inhibited the expression of IgM but not Syk, suggesting that Phx has a mode of action distinct from both of these reagents.

Figure 3.

Effect of Phx, actinomycin D and cycloheximide on IgM expression. Cells were treated with either 100 μM Phx (a), 5 μg ml−1 actinomycin D (b) or 30 μg ml−1 cycloheximide (c) for the indicated times. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting analysis using anti-IgM, anti-Syk, and anti-α-tubulin antibodies. The results from one representative experiment that was repeated three times are shown.

Treatment with Phx reduces the expression of IgM both at cell surface and in inside the cell

B cells produce and store immunoglobulin in intracellular organelles. To examine the effect of Phx on the expression of BCR at the cell surface we performed confocal microscopic studies. B cells were stained with anti-IgM and Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies to allow visualization of the surface IgM component of the BCR. At basal stage, IgM was uniformly distributed around the cell periphery (Figure 4a). Cells treated with Phx for 12 h exhibited highly diminished expression of BCR at the cell surface (Figure 4b). When cells were stimulated with anti-IgM antibody (M4), the surface IgM formed numerous membrane patches (Figure 4c). Treatment with Phx reduced the patch formation by cell surface IgM after BCR stimulation (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Effect of Phx on IgM expression both around cell surface and in TGN. Cells (106 cells ml−1) were treated with (b, d, f) or without (a, c, e, g–i) 50 μM Phx for 12 h and then were attached to coverslips pre-coated with poly-L-lysine. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with goat anti-chicken IgM plus Cy3-conjugated anti-goat IgG antibodies (a–g, i). Cells were stimulated with M4 (4 μg ml−1) in medium for 5 min at 37°C, and then fixed and stained (c, d). Cells fixed with paraformaldehyde were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and then stained (e, f). Phx-untreated cells were analysed by double-staining (i) with anti-IgM plus Cy3-conjugated anti-goat IgG (g) and anti-TGN38 plus FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (h) antibodies. The results from one representative experiment that was repeated three times are shown.

Next, we examined the effect of Phx on IgM expression in intracellular sites. Cells were permeabilized with Triton X-100 and analysed by confocal microscopy. In control cells, many patches appeared with strong IgM immunostaining (Figure 4e), whereas treatment with Phx reduced these patches containing IgM immunostaining (Figure 4f). To distinguish whether the immunofluorescent patches were the vesicles which transport IgM from trans-Golgi network (TGN) to plasma membrane or the vesicles which degrade IgM, we performed double-staining with anti-TGN38 antibody, a marker for TGN. As shown in Figure 4i, the yellow staining indicated colocalization of TGN38 (Figure 4h) and IgM (Figure 4g), suggesting that IgM immunofluorescent patches were located in the TGN.

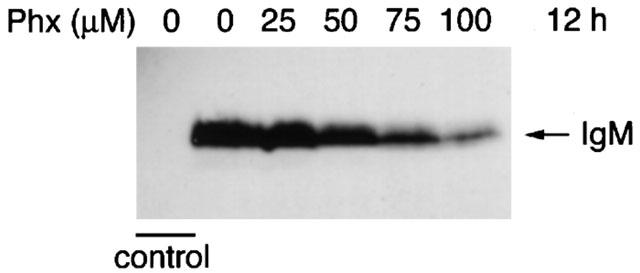

Treatment with Phx reduces IgM secretion from B cells

The immunofluorescent staining demonstrated that treatment with Phx reduced the expression of IgM both at the cell surface and in the TGN. To confirm whether the decrease in IgM in the TGN after treatment with Phx is due to the enhancement of IgM secretion into the medium, we analysed the amount of IgM in each culture medium using immunoblotting with anti-IgM antibody. Treatment with Phx for 12 h diminished IgM secretion in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5). These findings indicate that treatment with Phx reduces the secretion of IgM.

Figure 5.

Effect of Phx on secretion of IgM. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS in the presence of the indicated concentrations of Phx for 12 h. The culture medium supernatants were analysed with anti-IgM immunoblotting. Control shows RPMI1640 cultured medium with 10% serum only. Results shown are from one representative experiment that was replicated three times.

Treatment with a proteasomal inhibitor, MG-132, restores IgM levels

To clarify the mechanism of Phx-mediated down regulation of IgM, we tested the effects of a protease inhibitor of the 26S proteasome, MG-132, on IgM, Syk and α-tubulin expression by immunoblotting. IgM expression after Phx treatment (Figure 6a middle lane) was at about 45% of control levels (Figure 6a left lane). After treatment with MG-132 (50 μM, 12 h), IgM levels (Figure 6a right lane) became nearly equal to control, whereas Syk and α-tubulin levels remained unchanged throughout. In contrast with Phx, cycloheximide-induced down-regulation (Figure 6b middle lane) was not affected by MG-132 (Figure 6b right lane). These results suggest that Phx specifically accelerates degradation of IgM.

Figure 6.

Treatment with proteasomal inhibitor, MG-132, restores IgM level. Cells were treated with (a) 50 μM Phx or (b) 30 μg ml−1 cycloheximide, with or without 50 μM MG-132 for 12 h. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting analysis using anti-IgM, anti-Syk and anti-α-tubulin antibodies. The results from one representative experiment that was repeated three times are shown.

Discussion

The novel phenoxazine derivative, Phx, has shown inhibitory effects on the proliferation of various cancer cell lines (Ishida et al., 1996; Abe et al., 2001; Shimamoto et al., 2001). In addition, it has been reported that Phx markedly reduces the growth of tumours in mice which have received a leukemia cell or a carcinoma cell transplant, without causing adverse effects such as loss of body weight and leukopenia (Mori et al., 2000; Shimamoto et al., 2001). Thus, Phx is expected to be available as a new anti-tumour drug in the future. In this paper, we further suggest that Phx has suppressive effects on immunoglobulin expression in B cells and might be useful as a new immunosuppressive agent.

We have demonstrated that treatment with Phx induces a reduction in IgM expression in B cells. The finding that IgM expression at the cell membrane was reduced by Phx treatment led us to expect that Phx either enhances the degradation of IgM or inhibits IgM production. IgM production is accomplished through RNA transcription and protein synthesis. When actinomycin D, an inhibitor of transcription, inhibited IgM production after 32 h of treatment, the other cellular proteins also decreased at the same time implying a general inhibition of protein synthesis. Although actinomycin D is known to inhibit the activity of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase to intercalate DNA, Phx has no DNA intercalating activity (Ishida et al., 1996). This suggests that Phx has a mode of action different from actinomycin D. Cycloheximide, which inhibits peptidyl-translocation in ribosome, also reduced the level of proteins. Treatment with Phx decreased the expression of IgM, but not Syk or α-tubulin. However, B cells exposed to actinomycin D or cycloheximide exhibited a decrease in Syk, α-tubulin expression as well as in IgM expression. DT40 cells maintained in a serum containing medium continuously produce and secrete IgM. Treatment with Phx inhibited IgM production which led to diminished secretion of IgM.

It has been previously reported that Phx suppresses proliferation of cancer cells by inducing apoptosis. Also this study does not exclude the possibility that Phx may promote apoptosis if DT40 cells are treated with Phx for a longer time. However the present results, that Phx specifically decreased IgM expression suggest that the mechanism of Phx-induced inhibition of proliferation is different from apoptosis. This is supported by the following observations: (1) Phx specifically decreased the amount of IgM, while it maintained the levels of other proteins; (2) In the presence of Phx (<50 μM) the percentage of nonviable cells remained at less than 2%, the same level as the untreated controls; (3) Apoptotic DNA degradation did not occur at 50 μM Phx (12 h) whereas IgM expression decreased (data not shown). Since MG-132, which is a proteasomal inhibitor, increased IgM to the same level as the control (Figure 6), Phx has the effect of accelerating specific degradation of IgM. Phx may normalize the abnormal enhancement of immunoglobulin production in some diseases, such as autoimmune diseases and multiple myeloma. Phx is thus expected to be available for therapeutic purposes in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr S. Jahangeer for critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- BCR

B cell antigen receptor

- emodin

1,3,8-trihydroxy-6-methylanthraquinone

- FCS

foetal calf serum

- PHA

phytohemagglutinin

- Phx

2-amino-4,4α-dihydro-4α,7-dimethyl-3H-phenoxazine-3-one

- TGN

trans-Golginetwork

References

- ABE A., YAMANE M., TOMODA A. Prevention of growth of human lung carcinoma cells and induction of apoptosis by a novel phenoxazinone, 2-amino-4, 4α-dihydro-4α, 7-dimethyl-3H-phenoxazine-3-one. Anticancer Drugs. 2001;12:377–382. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200104000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AKAZAWA M., KOSIBU-KOIZUMI J., IWAMOTO T., TAKASAKI M., NAKAMURA M., TOMODA A. Effect of novel phenoxazine compounds, 2-amino-4, 4α-dihydro-4α, 7-dimethyl-3H-phenoxazine-3-one and 3-amino-1, 4α-dihydro-4α, 8-dimethyl-2H-phenoxazine-2-one on proliferation of phytohemagglutinin- or anti-human IgM-activated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:185–192. doi: 10.1620/tjem.196.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN C.L., LEHMEYER J.E., COOPER M.D. Evidence for an IgD homologue on chicken lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 1982;129:2580–2585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDBERG I.H., FRIEDMAN P.A. Antibiotics and nucleic acids. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1971;40:775–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.40.070171.004015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANG H.C., CHANG J.H., TUNG S.F., WU R.T., FOEGH M.L., CHU S.H. Immunosuppressive effect of emodin, a free radical generator. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;211:359–364. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90393-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANG H.C., CHU S.H., CHAO P.D. Vasorelexants from Chinese herbs, emodin and scoparone, possess immunosuppressive properties. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991;198:211–213. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90624-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIDA R., YAMANAKA S., KAWAI H., ITO H., IWAI M., NISHIZAWA M., HAMATAKE M., TOMODA A. Antitumor activity of 2-amino-4, 4α-dihydro-4α, 7-dimethyl-3H-phenoxazine-3-one, a novel phenoxazine derivative produced by the reaction of 2-amino-5-methylphenol with bovine hemolysate. Anticancer Drugs. 1996;7:591–595. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199607000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORI H., HONDA K., ISHIDA R., NORITA T., TOMODA A. Antitumor activity of 2-amino-4, 4α-dihydro-4α, 7-dimethyl-3H-phenoxazine-3-one against Meth A tumor transplanted into BALB/c mice. Anticancer Drugs. 2000;11:653–657. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200009000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOTOHASHI N., MITSCHER L.A., MEYER R. Potential antitumor phenoxazines. Med. Res. Rev. 1991;11:239–294. doi: 10.1002/med.2610110302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SADA K., TAKANO T., YANAGI S., YAMAMURA H. Structure and function of Syk protein-tyrosine kinase. J. Biochem. 2001;130:177–186. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIMAMOTO T., TOMODA A., ISHIDA R., OHYASHIKI K. Antitumor effects of a novel phenoxazine derivative on human leukemia cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Clinical Cancer Research. 2001;7:704–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKATA M., SABE H., HATA A., INAZU T., HOMMA Y., NUKADA T., YAMAMURA H., KUROSAKI T. Tyrosine kinases Lyn and Syk regulate B cell receptor-coupled Ca2+ mobilization through distinct pathways. EMBO J. 1994;13:1341–1349. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOMODA A., ARAI S., ISHIDA R., SHIMAMOTO T., OHYASHIKI K. An improved method for the rapid preparation of 2-amino-4, 4α-dihydro-4α, 7-dimethyl-3H-phenoxazine-3-one, a novel antitumor agent. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:1057–1058. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOMODA A., ARISAWA M., KOSHIMURA S. Oxidative condensation of 2-amino-4-methylphenol to dihydrophenoxazinone compound by human hemoglobin. J. Biochem. 1991;110:1004–1007. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOMODA A., HAMASHIMA H., ARISAWA M., KIKUCHI T., TEZUKA Y., KOSHIMURA S. Phenoxazinone synthesis by human hemoglobin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1992;1117:306–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOMODA A., YAMAGUCHI J., KOJIMA H., AMEMIYA H., YONEYAMA Y. Mechanism of o-aminophenol metabolism in human erythrocytes. FEBS Lett. 1986;196:44–48. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WADKINS R.M., JARES-ERIJMAN E.A., KLEMENT R., RUDIGER A., JOVIN T.M. Actinomycin D binding to single-stranded DNA: sequence specificity and hemi-intercalation model from fluorescence and 1H NMR spectroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;262:53–68. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]