Abstract

The mechanism and receptor subtypes involved in carbachol-stimulated amylase release and its changes after castration were studied in parotid slices from male rats.

Carbachol induced both amylase release and inositol phosphate (IP) accumulation in parotid slices from control and castrated rats, but castration induced a decrease of carbachol maximal effect. The effect of castration was reverted by testosterone replacement.

The selective M1 and M3 muscarinic receptor antagonists, pirenzepine and 4-diphenylacetoxy-N-methylpiperidine methiodide, respectively, inhibited carbachol-stimulated amylase release and IP accumulation in a dose-dependent manner in parotid slices from control and castrated rats.

A diminution of binding sites of muscarinic receptor in parotid membrane from castrated rats was observed. Competition binding assays showed that both, M1 and M3 muscarinic receptor subtypes are expressed in membranes of parotid glands from control and castrated rats, M3 being the greater population.

These results suggest that amylase release induced by carbachol in parotid slices is mediated by phosphoinositide accumulation. This mechanism appears to be triggered by the activation of M1 and M3 muscarinic receptor subtypes. Castration induced a decrease of the maximal effect of carbachol evoked amylase release and IP accumulation followed by a diminution in the number of parotid gland muscarinic acetylcholine receptors.

Keywords: Carbachol, parotid gland, amylase, inositol phosphates, castration, binding assays

Introduction

Saliva is one of the most important fluids because of the multiple functions it plays in different organic processes, being the first digestive barrier against infections and helping in the articulation of words and swallowing.

The loss of salivary gland function and thus saliva production can be induced by changes in dietary consistency, radiation therapy and medications as well as viral, genetic or autoimmune diseases (Herrera et al., 1988; Fox, 1989; Bacman et al., 1996). Besides, salivary glands are tissues sensitive to hormones (Prabir, 1996). The parotid gland provides 50% or more of the stimulated enzyme rich saliva. Amylase is one of the enzymes that participate in the protective, digestive and antibacterial functions of the saliva. Secretagogues promote amylase secretion by cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and calcium-mediated processes. Moreover, β-adrenergic receptors express their effects through the activation of adenylate cyclase and an increase in cAMP (Brooks et al., 1995). Calcium-mobilizing agonists, which include those that activate α-adrenergic and muscarinic receptors, stimulate phospholipase C (PLC) to catalyze the breakdown of phosphatidylglycerol, where inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) releases cellular calcium by interacting with a specific receptor site on the endoplasmic reticulum and diacylglycerol activates protein kinase C (PKC) (Horn et al., 1988).

It has been demonstrated by binding studies that rat parotid membrane possesses only one pharmacologically detectable muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (mAChR) subtype, characterized as M3 (Dai et al., 1991). However, immunoprecipitation of muscarinic receptors from mouse parotid membranes by specific subtype antisera showed that M3 subtype represented 75%, while M1 subtype represented 25% of the total number of precipitable receptors (Watson et al., 1996).

The aim of the present study was, on the one hand, to determine the different signalling events involved in the M3 and M1 receptor activation-dependent amylase release in male rat parotid gland. On the other hand, we wanted to investigate whether castration induced changes in cholinoceptor subtype expression and activation. Therefore, we studied whether (i) carbachol stimulation of M3 and M1 receptor subtypes exerted amylase release and stimulation of inositol phosphates (IPs); (ii) if carbachol-evoked amylase release was associated with PLC, PKC and nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activity, and (iii) if testosterone might be related to differential expression of mAChR subtypes and/or changes in functional activity of these receptors with regard to amylase release and phosphoinositide accumulation.

Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats weighing 250–300 g were used throughout. Animals had free access to food and water until the night before experiments when food, but not water, was withdrawn. The following experimental groups were used: (a) control animals; (b) castrated animals and (c) castrated testosterone-treated animals. Castration was performed under ether anesthesia by removing testicles through bilateral cuts in the scrotum 21 days before experiments, and testosterone replacement treatment of castrated rats was carried out by injecting testosterone (1 mg/100 g body weight) in 0.20 ml absolute ethanol s.c., beginning at 15 days after castration and daily thereafter for 7 days (Busch et al., 2000). Control castrated rats received 0.20 ml absolute ethanol. Animals were cared according to ‘The Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals' (DHEW Publication, NIH 80–23).

Experimental procedure for amylase assay

Free connective tissue and fat were gently removed from parotid glands under a magnifying glass, and the anterior lobe was cut into small slices that were placed in tubes containing 500 μl of Krebs Ringer bicarbonate (KRB) solution pH 7.4 without glucose and with 5 mM β-hydroxybutyric acid, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. When used inhibitors were included from the beginning of the incubation time and carbachol was added in the last 10 min. The total amylase content or that released into the medium was determined by the method described by Bernfeld (1951) using starch suspension as the substrate. Aliquots of the incubation medium and of the supernatants of the homogenized glands were incubated at 20°C with a 1% starch suspension during 3 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of dinitro-salicylic acid solution. After 5 min in a boiling water bath, absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 540 nm. Amylase activity in the medium was expressed as a percentage of the total activity.

Measurement of IPs in parotid slices

IP levels were measured using a method modified from Berridge et al. (1982). Parotid slices were labeled for 120 min at 37°C in 500 μl of KRB with 1 μCi of myo-[3H]-inositol ([3H]-MI) (Sp. Act. 15 Ci mmol−1), from Dupont/New England Nuclear (Washington, DC, U.S.A.), and LiCl (10 mM) and then washed three times in fresh KRB medium. Thereafter slices were incubated in KRB with 10 mM LiCl for 60 min. When inhibitor drugs were used, they were added 20 min before the carbachol. The cholinergic agonist was allowed to react the last 10 min. The reaction was stopped by removing the parotid slices and homogenizing in tubes containing 300 μl of KRB with LiCl (10 mM) and 2 ml of chloroform/methanol (1 : 2 v v−1). Chloroform (0.62 ml) and 1 ml of water were added to separate the phases. After centrifugation, a portion (2 ml) of the upper phase was removed for analysis of the water-soluble [3H]-MI-labelled compounds. Water-soluble extracts were applied to a 1.6 ml column of Bio-Rad AG 1 × 8 anion exchange resin equilibrated in 10 mM Tris-formic acid pH 7.4 and then 0.1 M formic acid. The first peak was eluted with 5 mM myo-inositol and the second peak (IPs) was eluted with 1 M ammonium formate in 0.1 M formic acid. Fractions (1 ml) were recovered and radioactivity was determined by scintillation counting. Peak areas were determined by triangulation and results of the second peak (IPs) were expressed as the absolute values of the area under the curve following the criteria of Simpson's equation. In order to determine the absence of [3H]-myo-inositol in the eluted peaks of IPs, chromatography in silica gel 60 F254 sheets (Merck) was performed using propan-2-ol/6, NH4 (14 : 5) as the developing solvent (Hokin-Neaverson & Sadeghian, 1976). Spots were located by spraying with freshly prepared 0.1% ferric chloride in ethanol followed, after air-drying, with 1% sulphosalicylic acid in ethanol. To assay the radioactivity a histogram was constructed by cutting up the sheet gel, placing each sample in Triton-toluene based scintillation fluid and then counting (Sterin-Borda et al., 1995).

Radioligand binding assays

Parotid glands were freed of connective tissue, fat and lymph nodes and then homogenized in Ultraturrax in 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) supplemented with the following protease inhibitors: 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg ml−1 leupeptin, 1 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 1 mM sodium ethylenediaminotetra-acetate (EDTA), 2 μM pepstatin A and 1 mM iodoacetamide. The slurry was then centrifugated for 30 min at 40,000 × g at 4°C to recover a plasma membrane-enriched fraction (Yamamoto et al., 1996). For binding experiments, the plasma membrane-enriched fraction was resuspended in the same Tris buffer described above at a concentration approximately of 500 μg ml−1. Saturation assay was determined by incubation of 200–300 μg of protein with 0.5–50 nM of the muscarinic antagonist [3H]-quinuclidinyl benzilate ([3H]-QNB, NEN TM Life Science Products, Inc., Boston, MA, U.S.A.) in a total volume of 150 μl for 1 hour at 37°C with continuous shaking. Binding was stopped by adding 2 ml of ice-cold buffer followed by rapid filtration (Whatman GF/c). Filters were rinsed with 12 ml of ice-cold buffer, transferred into vials containing 10 ml of scintillation cocktail and counted in a liquid scintillation spectrometer. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 1 μM atropine and never exceeded 10% of the total binding. Radioactivity bound was lower than 10% of total counts. For competition binding assays, membranes (200–300 μg protein) were incubated with about 800 pM [3H]-QNB and increasing concentrations of selective antagonists and the experiment was carried out as described above.

Drugs

Carbachol, pirenzepine, atropine, staurosporine, NG-methyl-L-Arginine (L-NMMA) and trifluoperazine (TFP) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.); U-73122 and 4-diphenylacetoxy-N-methylpiperidine methiodide (4-DAMP) from RBI (Narick, MA, U.S.A.); AF-DX 116, tropicamide and benzoquinonium dibromide are from Tocris Cookson Inc. The drugs were diluted in the bath to achieve the final concentration stated in the text.

Data analysis

Student's t-test for unpaired values was used to determine the levels of significance. When multiple comparisons were necessary after analysis of variance, the Student–Newman–Keuls multiple comparison test was applied. Differences between means were considered significant if P<0.05. The competition curves were analyzed by linear regression. Schild analysis was used for pA2 determinations of the antagonists.

Results

To assess the influence of castration on amylase secretion by parotid gland, concentration–response curves of carbachol in parotid slices from control and castrated rats were performed. Figure 1a shows that no difference was observed in basal values and in the secretory response to low concentrations of carbachol (1 × 10−7–1 × 10−5 M) between control and castrated preparations. However, while in normal slices, the increment of carbachol concentration up to 1 × 10−3 M was followed by an increase of amylase release (100% of increment, P<0.001); in castrated slices increasing concentrations of carbachol showed no enhancement on amylase secretion. The maximal effect achieved was of 50% (P<0.01) over basal values. Since the maximal effects for each castrated and control groups are different, one could expect that EC50 also should be different. This is the case observed in our work (7.9 × 10−7 M for castrated rat and 1.4 × 10−5 M for control rat). Testosterone replacement reversed the effect of castration in carbachol-induced amylase release (Figure 1a). As observed in Figure 1b, in control and castrated preparations, the nonselective muscarinic-receptor antagonist atropine (1 × 10−7 M) inhibited the stimulatory effect of carbachol. It is important to note that the basal values of amylase content in the gland were not modified by castration (total amylase activity/mg wet weight: normal 40.4±4; castrated 49.2±5; n: 40).

Figure 1.

Panel (a) Concentration-dependent effect of carbachol on amylase release in parotid slices from control, castrated and castrated testosterone-treated male rat. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. of six experiments in each group. Panel (b) Effect of atropine (1 × 10−7 M), U-73122 (5 × 10−6 M), TFP (5 × 10−6 M), staurosporine (1 × 10−9 M) and L-NMMA (1 × 10−4 M) on carbachol-induced amylase release on parotid slices from control and castrated rat, represented as the percentage of carbachol maximal effect. A: carbachol (1 × 10−3 M); B: atropine; C: U-73122; D: TFP; E: staurosporine; F: L-NMMA. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. of six experiments in each group.

To determine if there were changes in the postreceptor mechanisms involving G protein function and PLC, we studied PKC and NOS - protein kinase G signalling, in control and castrated rats. With this purpose, we explored the action of U-73122 (5 × 10−6 M), staurosporine (1 × 10−9 M), TFP (5 × 10−6 M) and L-NMMA (5 × 10−6 M). As can be seen in Figure 1b, inhibition of PLC and calcium-calmodulin prevented the maximal effect of carbachol-induced amylase release in parotid slices from control and castrated rats. Staurosporine and L-NMMA did not modify the secretory response to carbachol on any of the preparations. This last experiment indicates that neither PKC nor NOS participates in the secretory response (Figure 1b).

To assess if carbachol was related to IP turnover in rat parotid slices, IP accumulation was measured. As can be seen in Figure 2a, the basal values and IPs accumulation in response to low concentrations of carbachol (1 × 10−7–1 × 10−5 M) were similar in both preparations. The maximal effect of carbachol was lower in slices from castrated rats compared to the control ones (1 × 10−5 and 1 × 10−3 M, respectively), leading to the decreased EC50 observed in the castrated group. Testosterone replacement abolished the inhibitory influence of castration on carbachol-evoked IPs accumulation (Figure 2a). The nonselective mAChR antagonist, atropine (1 × 10−7 M) and the PLC inhibitor by U-73122 (5 × 10−6 M) prevented carbachol-induced IPs accumulation in both control and castrated preparations (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Panel (a) Concentration-dependent effect of carbachol on IP accumulation in parotid slices from control, castrated and castrated testosterone-treated male rat. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. of six experiments in each group. Panel (b) Effect of atropine (1 × 10−7 M) and U-73122 (5 × 10−6 M) on carbachol-induced IP accumulation on parotid slices from control and castrated rats, represented as the percentage of carbachol maximal effect. A: carbachol (1 × 10−3 M); B: atropine; C: U-73122. Results are expressed as the mean±s.e.m. of six experiments in each group.

To determine the subtype of mAChR (M1–M4) responsible for amylase secretion and IPs accumulation, the respective antagonists pirenzepine, AF-DX 116, 4-DAMP and tropicamide, were selectively studied. Figure 3 and Figure 4 show that M1 and M3 antagonists induced a parallel right shift of the dose–response curves to carbachol, using concentrations not higher than 10−2 M, to avoid osmotic effects. A competitive block were observed in all preparations. This is demonstrated by the absence of an effect on the maximal response to carbachol and by the slopes of the Schild plots, which were close to unity (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Neither of the used antagonists modified basal values at concentrations up to 10−5 M (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Antagonism of muscarinic receptor-stimulated amylase release by 4-DAMP and pirenzepine in parotid slices from control (upper panel) and castrated (lower panel) male rat. Parotid slices were preincubated in the absence or presence of indicated concentrations of 4-DAMP (a) or pirenzepine (b) added 20 min before the agonist, followed by determination of carbachol dose-dependent stimulation of amylase release as described in Methods. (c) Schild plots of 4-DAMP and pirenzepine antagonism of carbachol-mediated amylase release by parotid slices from control and castrated male rats. Logs of dose ratios minus 1 are from data shown in (a) and (b), and are plotted as a function of the pAx of the antagonist. Results shown are one of four experiments with similar results.

Figure 4.

Antagonism of muscarinic receptor-stimulated IP accumulation by 4-DAMP and pirenzepine in parotid slices from control (upper panel) and castrated (lower panel) male rat. Parotid slices were preincubated in the absence or presence of indicated concentrations of 4-DAMP (a) or pirenzepine (b) added 20 min before the agonist, followed by determination of carbachol dose-dependent stimulation of IP accumulation as described in Methods. (c) Schild plots of 4-DAMP and pirenzepine antagonism of carbachol-mediated IP accumulation by parotid slices from control and castrated male rats. Logs of dose ratios minus 1 are from data shown in (a) and (b), and are plotted as a function of the pAx of the antagonist. Results shown are one of four experiments with similar results.

Differential potency for amylase release and IP accumulation are shown in Table 1. In control preparation, 4-DAMP>pirenzepine (P<0.001 for amylase and P<0.05 for IP, respectively) while in the castrated ones 4-DAMP=pirenzepine. However, no differences were observed between castrated and control animals in the antagonistic effect of 4-DAMP, while pirenzepine was more potent (P<0.01) in inhibiting amylase release in the castrated ones.

Table 1.

Potencies of muscarinic antagonists in inhibiting amylase release and inositol phosphate accumulation in parotid slices from control and castrated male rats

| Antagonist | Amylase release | Inositol phosphate accumulation | ||

| pA2 | Slope | pA2 | Slope | |

| 4-DAMP (normal) | 8.63±0.8 | −0.751 | 9.3±0.9 | −1.186 |

| Pirenzepine (normal) | 7.20±0.7a | −0.802 | 8.2±0.8b | −0.867 |

| 4-DAMP (castrated) | 8.12±0.8 | −0.911 | 8.6±0.9 | −1.200 |

| Pirenzepine (castrated) | 8.10±0.7 | −0.854 | 8.4±0.8 | −1.278 |

Table 2 shows that neither AF-DX 116 nor tropicamide modified carbachol EC50 for both amylase release and IPs production. These results exclude the participation of M2 and M4 muscarinic receptor subtypes in carbachol action on parotid slices. Since benzoquinonium was not able to modify carbachol EC50 (Table 2), the participation of the nicotinic receptor was also excluded.

Table 2.

Carbachol EC50 (M) in amylase release and IP production in the absence and the presence of the antagonists of the M2, M4 and nicotinic receptors

| Additions | Control | Castrated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amylase | IP | Amylase | IP | |

| None | 1.54 × 10−5 | 1.78 × 10−5 | 9.88 × 10−7 | 7.94 × 10−7 |

| AF-DX 116 | 1.58 × 10−5 | 2.19 × 10−5 | 7.40 × 10−7 | 7.20 × 10−7 |

| Tropicamide | 1.41 × 10−5 | 1.66 × 10−5 | 7.90 × 10−7 | 8.10 × 10−7 |

| Benzoquinonium | 1.35 × 10−5 | 2.00 × 10−5 | 8.50 × 10−7 | 7.94 × 10−7 |

Parotid slices were preincubated in the absence or presence of 1 × 10−5 M of the antagonists added at the beginning of the incubation time, followed by determination of carbachol dose-dependent stimulation of amylase release or IP production as described in Methods. Results shown are one of four experiments with similar results.

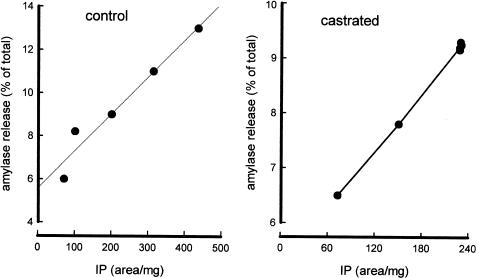

Linear regression analysis shows a positive correlation between amylase release and IP accumulation on control and castrated preparations (Figure 5). This is in agreement with the assumption that amylase release induced by carbachol is a consequence of IP accumulation.

Figure 5.

Correlation between IP accumulation and amylase release in parotid slices from control and castrated male rat. The data were obtained from Figure 1 and Figure 2, and amylase release was plotted as a function of the IP accumulation. Correlation values: 0.9747 and 0.9992 for control and castrated animals, respectively.

To elucidate whether the decrease of the secretory response in castrated rats could be because of changes in the number and/or affinity of mAChR, radioligand binding studies were performed using [3H]-QNB in different experimental conditions. Figure 6 shows a decrease in the binding number sites (Bmax) in castrated rat membranes compared with those of controls with no significant changes in affinity (Kd) (Kd: control: 0.186±0.024 nM; castrated: 0.203±0.029 nM; Bmax: control: 65.8±2.28 fmol mg protein−1; castrated: 47.2±1.84 mg protein−1; P<0.001). Testosterone increased Bmax in castrated membranes reaching values similar to those observed in control rats (58.6±1.52 fmol mg protein−1) without changes in the Kd values (0.192±0.018 nM). The relative potencies of selective antagonists on parotid membranes from control, castrated and castrated testosterone-treated rats indicate a predominant expression of M3 mAChR population, regardless of the castration or castration-treated with testosterone (Figure 7). Castration decreased pirenzepine Ki value (nM) (control: 189.2±11; castrated 61.5±5, P<0.001) and this effect was restored in testosterone-treated rats (193.3±13). On the other hand, Ki values of 4-DAMP (control: 18.8±1.6; castrated 20.4±1.7; castrated testosterone-treated: 19.4±1.5) and atropine (control: 5.7±0.3; castrated 6.0±0.4; castrated testosterone-treated: 4.9±0.3) were neither modified in castrated nor in castrated testosterone-treated rats.

Figure 6.

Saturation curves (a) and Scatchard plots (b) on rat parotid gland membranes from control, castrated and castrated testosterone-treated rats, incubated with different concentrations of [3H]-QNB. The results shown are the mean of four experiments performed in duplicate in each group.

Figure 7.

Competition binding assays of muscarinic antagonists with [3H]-QNB in parotid membranes from control (a), castrated (b) and castrated testosterone-treated (c) rats. Parotid gland membranes were obtained and competition binding assays were performed as indicated in the text with the muscarinic antagonists atropine, 4-DAMP and pirenzepine. Results shown are representative of three separate experiments performed in duplicate with similar results. % B means per cent of [3H]-QNB bound.

Discussion

The current studies give a new insight into the secretory action of carbachol. The results suggest that in parotid glands from male rat, amylase release is triggered by the activation of M1 and M3 mAChR, which in turn induces the activation of PLC. Amylase secretion seems to be a result of IP turnover. Following castration amylase secretion and IP accumulation decrease. This is related to a decrease in mAChR expression.

Several results support these conclusions. Carbachol induced a concentration-dependent amylase release and IP accumulation in parotid slices from male rats. Amylase secretion correlates with IP accumulation supporting the view that amylase release is mediated mainly by phosphoinositide turnover. In addition, when PLC or calcium calmodulin were inhibited by U-73122 and TFP, respectively, the secretory effect of carbachol was also blocked. Atropine inhibited in a similar way the maximal effect of carbachol-induced amylase release and IP accumulation. On the other hand, the fact that neither staurosporine nor L-NMMA were able to inhibit carbachol effect strongly indicates that amylase release in the present study is independent of both PKC and NOS. In previous works, it has been described that nitric oxide appeared to mediate amylase release induced by carbachol (Rosignoli & Perez-Leiros, 2002). The discordance observed here could be because of the NOS antagonist used in our study. Since L-NMMA shows no affinity to mAChRs (Buxton et al., 1993), the nonspecific mAChR antagonism observed with other alkyl esters of arginine should be ruled out.

Castration decrease of carbachol-induced amylase release observed after castration might not be related to lower levels of total amylase content in the gland. This idea is supported by the fact that basal amylase activities in each of the control and castrated rats do not differ from each other. This indicates that amylase synthesis is not under testosterone influence. However, it is well known that testosterone regulates the expression of genes of a number of proteins, enzymes and growth factors in salivary glands (Rosinski-Chupin & Rougeon, 1990).

Binding studies showed that mAChR expression was diminished in sites after castration without any alteration in the equilibrium dissociation constant. Thus, the differences in EC50 and maximal effect of carbachol could be related to the decrease in the number of binding sites.

The pharmacological analysis with mAChR antagonists supports the hypothesis that M3 and M1 subtypes are important mediators of carbachol biological effects in parotid gland, while M2 and M4 subtypes seem to have no relevance. The muscarinic receptor subtype M3 has been described as the muscarinic receptor predominant in parotid glands from rat (Dai et al., 1991) and mouse (Watson et al., 1996). The second muscarinic receptor subtype described in salivary glands is the M1 (Dai et al., 1991; Watson et al., 1996; Yamamoto et al., 1996; Pérez Leirós et al., 2000). Therefore, our results satisfy the pharmacological criteria for the coexistence of M3 and M1 mAChR in parotid gland that change after castration and is restored by testosterone treatment. The 4-DAMP potency in inhibiting carbachol-induced IP production in our study is in concordance with that obtained for Dai et al. (1991). In control rats, 4-DAMP was 10 times more potent than pirenzepine in the inhibition of both amylase release and IP accumulation. This result is in agreement with the respective Ki of the antagonists obtained by the competition binding assays. However, the ability of pirenzepine in inhibiting the effect of carbachol suggests that pirenzepine-M1-sensitive receptor may play an important role in the parotid gland functions. This ability of the M1 receptor subtype antagonist in inhibiting amylase release was previously described in pancreatic acinar cells (Schmid et al., 1998; Kato et al., 1992). The relative potencies of both antagonists for inhibiting carbachol-stimulated amylase release were similar to their relative potencies for blocking carbachol-induced IP accumulation.

Castration decreased total muscarinic receptor expression in parotid gland increasing the relation between M1/M3 mAChR subtypes as observed in the minor Ki value for M1. It might be very interesting to study the reason for the decreases expression of M3 mAChR subtype.

When analyzing the pharmacological profile in castrated rats for amylase release and IP accumulation, it was observed that the pA2's of each 4-DAMP and pirenzepine were similar. This could be related to the larger population of muscarinic M1 receptor subtype and the minor Ki value observed after castration. On the other hand, castration induced changes in pirenzepine antagonism action to amylase release but not to IP accumulation. This divergence could be because of the existence of parallel pathway posterior to IP production depending on the receptor subtype activated. In castrated rats, the M1 receptor subtype-activated cascade would be more sensible to the blockade by pirenzepine. Further studies, as the alkylation of the muscarinic M3 receptor subtype, can give more indication about the presence and the role of the muscarinic M1 receptor subtype, in parotid glands from castrated rats.

The result presented in this paper gives new insight about testosterone modulation on parotid gland parasympathetic system. Alterations in the salivary gland function could reflect an alteration in the endocrine status, which might be of great clinical relevance.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by Grants UBACYT from Buenos Aires University and PIP from CONICET, Argentina. We thank Mrs Elvita Vannucchi and Mrs Elena Vernet for their outstanding technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- 4-DAMP

4-diphenylacetoxy-N-methylpiperidine methiodide

- EDTA

sodium ethylenediaminetetra-acetate

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate

- IPs

inositol phosphates

- KRB

krebs Ringer bicarbonate

- L-NMMA

NG-methyl-L-arginine

- mAChR

muscarinic acetylcholine receptor

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLC

phospholipase C

- TFP

trifluoperazine

References

- BACMAN S., STERIN-BORDA L., CAMUSSO J.J., ARANA R., HUBSCHER O., BORDA E. Circulating antibodies against rat parotid gland M3 muscarinic receptors in primary Sjögren's Syndrome. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1996;104:454–459. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.42748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERNFELD P. Enzymes of starch degradation and synthesis. Adv Enzymol. 1951;12:379–428. doi: 10.1002/9780470122570.ch7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERRIDGE M.J., DOWENS C.P., HAULEY M.R. Lithium amplifies agonist-dependent phosphatidyl inositol responses in brain and salivary glands. Biochem. J. 1982;206:587–595. doi: 10.1042/bj2060587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROOKS J.C., BROOKS M., PISKOROWSKI J., WATSON J.D. Amylase secretion by cultured porcine parotid cells. Arch. Oral Biol. 1995;40:425–432. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(94)00179-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUSCH L., WALD M., BORDA E. Influence of castration on the response of the rat vas deferens to fluoxetine. Pharmacol. Res. 2000;42:305–311. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2000.0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUXTON I.L.O., CHEEK D.J., ECKMAN D., WERTFALL D.P., SANDERS K.M., KEEF D.K. NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester and other alkyl esters of arginine are muscarinic receptors antagonists. Circ. Res. 1993;72:387–395. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAI Y., AMBUDKAR I.S., HORN V.J., YEH Ch., KOUSVELARI E.E., WALL S.J., LI M., YASUDA R.P., WOLFE B.B., BAUM B.J. Evidence that M3 muscarinic receptors in rat parotid gland couple to two second messenger systems. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;261:C1063–C1073. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.6.C1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOX P.C. Saliva composition and its importance in dental health. Compend. Cont. Educ. Dent. (Suppl). 1989;13:S456–S460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERRERA J.L., LYONS M.F., II, JOHNSON L.F. Saliva: its roles in health and disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1988;10:569–578. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198810000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOKIN-NEAVERSON M., SADEGHIAN K. Separation of 3H-inositol monophosphates and 3H-inositol on silica gel glass-fiber sheets. J. Chromatogr. 1976;120:502–505. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(76)80031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORN V.J., BAUM B.J., AMBUDKAR I.S. β-adrenergic receptor stimulation induces inositol trisphosphate production and Ca2+ mobilization in rat parotid acinar cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:12454–12460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATO M., OHKUMA S., KATAOKA K., KASHIMA K., KURIYAMA K. Characterization of muscarinic receptor subtypes on rat pancreatic acini: pharmacological identification by secretory responses and binding studies. Digestion. 1992;52:194–203. doi: 10.1159/000200953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEREZ LEIROS C., ROSIGNOLI F., GENARO A.M., SALES M.E., STERIN-BORDA L., BORDA E.S. Differential activation of nitric oxide synthase through muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in rat salivary glands. J. Auton. Nerv. Sys. 2000;79:99–107. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(99)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRABIR K.De. Sex-hormonal regulation of 20.5 and 24 kDa mayor male-specific proteins in Syrian hamster submandibular gland. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1996;58:183–187. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(96)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSIGNOLI F., PEREZ LEIROS C. Activation of nitric oxide synthase through muscarinic receptors in rat parotid gland. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;439:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSINSKI-CHUPIN I., ROUGEON F. A new member of the glutamine-rich protein gene family is characterized by the absence of internal repeats and the androgen control of its expression in the submandibular gland of rats. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:10709–10713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMID S.W., MODLIN I.M., TANG L.H., STOCH A., RHEE S., NATHANSON M.H., SCHEELE G.A., GORELICK F.S. Telenzepine-sensitive muscarinic receptors on rat pancreatic acinar cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:734–741. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.4.G734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STERIN-BORDA L., VILA ECHAGÜE A., PEREZ LEIROS C., GENARO A., BORDA E. Endogenous nitric oxide signalling system and the cardiac muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-inotropic response. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:1525–1531. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATSON E.L., ABEL P.W., DIJULIO D., ZENG W., MAKOID M., JACOBSON K.L., POTTER L.T., DOWD F.J. Identification of muscarinic receptor subtypes in mouse parotid gland. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:C905–C913. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.3.C905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAMOTO H., SIMS N.E., MACAULEY S.P., NGUYEN K.T., NAKAGAWA Y., HUMPHREYS-BEHER M.G. Alterations in the secretory response of non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice to muscarinic receptor stimulation. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1996;78:245–255. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]