Abstract

PURPOSE A seamless system of social, behavioral, and medical services for the uninsured was created to address the social determinants of disease, reduce health disparities, and foster local economic development in 2 inner-city neighborhoods and 2 rural counties in New Mexico.

METHODS Our family medicine department helped urban and rural communities that had large uninsured, minority populations create Health Commons models. These models of care are characterized by health planning shared by community stakeholders; 1-stop shopping for medical, behavioral, and social services; employment of community health workers bridging the clinic and the community; and job creation.

RESULTS Outcomes of the Health Commons included creation of a Web-based assignment of uninsured emergency department patients to primary care homes, reducing return visits by 31%; creation of a Web-based interface allowing partner organizations with incompatible information systems to share medical information; and creation of a statewide telephone Health Advice Line offering rural and urban uninsured individuals access to health and social service information and referrals 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The Health Commons created jobs and has been sustained by attracting local investment and external public and private funding for its products. Our department’s role in developing the Health Commons helped the academic health center (AHC) form mutually beneficial community partnerships with surrounding and distant urban and rural communities.

CONCLUSIONS Broad stakeholder participation built trust and investment in the Health Commons, expanding services for the uninsured. This participation also fostered marketable innovations applicable to all Health Commons’ sites. Family medicine can promote the Health Commons as a venue for linking complementary strengths of the AHC and the community, while addressing the unique needs of each. Overall, our experience suggests that family medicine can play a leadership role in building collaborative approaches to seemingly intractable health problems among the uninsured, benefiting not only the community, but also the AHC.

Keywords: Health Commons, community health care, family medicine, academic health centers, collaboration, uninsured, poverty, medically underserved area, primary care

INTRODUCTION

Intractable health problems in our society, such as health disparities between economic and ethnic groups, poor access to care, and alarming increases in uninsured populations, have as their root cause social determinants.1 The Health Commons is a conceptual model developed by the University of New Mexico (UNM) Department of Family and Community Medicine (the Department) in collaboration with its safety net stakeholders. This model attempts to address social determinants through integration and collaboration among many community stakeholders, pooling resources to address community-prioritized health needs. Funded by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Community Access Program (CAP), the Health Commons helps communities identify and mobilize resources at UNM, an academic health center (AHC).

The defining characteristics of New Mexico’s Health Commons models include the following:

Promoting universal access to primary care homes as a public health measure

Creating a seamless system providing medical, behavioral, dental, and social services that offers advanced case management, information systems, and links to community resources through community health workers

Expanding the training of community-based, interdisciplinary health professionals in needy communities

Developing pipelines to build a diverse work-force of health professionals

Ensuring the Health Commons becomes a source of local employment and economic development

Yet such collaborative approaches are given low priority within the AHC in favor of biomedical advances and attracting referrals to unique subspecialty areas.

Buttressed by the Future of Family Medicine’s call for greater community engagement,2 family medicine can catalyze the Health Commons of the future. Academic family medicine is well positioned to link traditional AHC strengths with broader community needs. Their graduates are on the frontline of community care and are better geographically distributed than those of any other specialty.

The Department in New Mexico is recognized as an innovator in rural medicine, in community-based medical education,3,4 and in service to rural and marginalized populations.5–8 Most of these innovations have focused on increased access to primary care. Today, the UNM Health Sciences Center faces dire financial constraints at a time when more New Mexicans are without health insurance and health disparities among its diverse populations grow. It is time to improve the health of the community by transforming the health care system to address disease risk and social determinants.9,10 Family medicine is uniquely positioned within the AHC to lead these efforts, while addressing the institution’s fiscal, public health, and quality responsibilities.

What follows are cases illustrating how this new model is being implemented in New Mexico, with Results focused on broader impacts of the Health Commons and their sustainability.

METHODS

UNM Care Program

Health Commons concepts emerged from the formation in 1997 of the UNM Care Program5 designed by the Department faculty and hospital administrators. In this program, uninsured, unassigned citizens residing in Bernalillo County and receiving care at the AHC were assigned a primary care home and charged affordable, sharply reduced co-pays for office visits, hospitalizations, tests, and medications. The AHC partnered with a community federally qualified health center (FQHC) network, First Choice, to help absorb the increased demand for primary care services. The program serves about 15,000 patients per year; one third are assigned to First Choice. With implementation of the program, use of preventive services increased, number of hospitalizations decreased, and the hospital saved more than $2 million per year, largely because of substantial decreases in number of hospital days per 1,000 enrollees in the program. But the program had little effect on high-risk patients with comorbidities.11 Focusing only on medical services failed to address this population’s underlying behavioral and social causes of disease.

Setting and Support

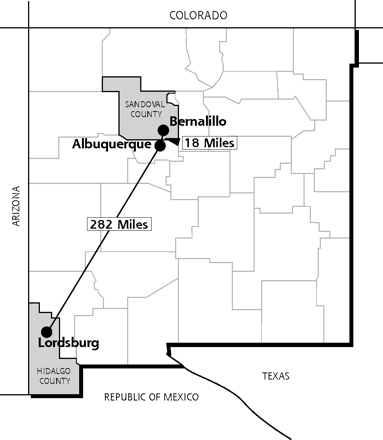

In recent years, the Department, in collaboration with its AHC, worked with a health consortium of safety net providers in 2 inner-city neighborhoods (South Valley and Southeast Heights, both in Albuquerque) and in 2 rural counties (Sandoval and Hidalgo) (Figure 1 ▶) to address the health needs of the uninsured by creating 4 unique Health Commons models. By linking with an AHC, each Health Commons provides a rich environment for high-quality service and innovative education. These communities, while diverse and geographically distant, share several characteristics. Brought together by leaders within the Department, the safety net partners serve disproportionately poor, uninsured, isolated minority populations. Each site is challenged by barriers to access, fragmentation of care, or limited services.

Figure 1.

Health Commons models were created in 2 inner-city neighborhoods (South Valley and Southeast Heights, both in Albuquerque) and in 2 rural counties (Sandoval and Hidalgo).

The 4 Health Commons were supported by the Central New Mexico CAP and the Department. The Department’s initial CAP collaborators included FQHCs, the Indian Health Service, an urban Indian health clinic, a homeless clinic, rural clinical services, and the New Mexico Health Department. The group later expanded to include behavioral and oral health and social service agencies.

Health Commons Models

The 4 Health Commons models that emerged from this collaboration are described below.

South Valley Health Commons

First Choice Community Healthcare, an FQHC, operates 11 sites offering primary, medical, dental, and behavioral health services, and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) services to 45,000 mostly uninsured and underinsured individuals and families. First Choice is UNM’s largest safety net partner. Its South Valley site sits in a predominantly poor, underserved community in Albuquerque with high rates of unemployment and high school dropout. Health services and social services are disconnected, and public transportation is inadequate.

Health Commons planners will colocate different agencies and, where feasible, integrate their services and operations in a single site. Ten million dollars was raised from federal, state, county, Department of Health, and UNM resources to build South Valley Health Commons, the largest of the 4 Health Commons.

This 42,000-square foot, 1-stop community service destination site will open in 2007. It will feature a community pharmacy, adult and child day care, a wellness center, an income support office, an eye clinic, and an occupational and physical therapy office. Other social service offices, as well as restaurants, will be housed on adjacent land and will support economic development and provide good jobs in this poor area of the city. To help youth stay in school and consider careers in health, this Health Commons will have a mentoring program run by university health professions faculty. Twelve family medicine residents will have their home clinics at this site.

Southeast Heights Center for Family Health

The Southeast Heights neighborhood is characterized by high mobility, ethnic diversity, poverty, and social stresses, including inadequate housing, isolation, violence, and substance abuse. This neighborhood is the entry point for poor migrants and immigrants into the greater society. Health Commons financing is provided at this site for primary care, children’s health, oral health, public health, and women’s health.

In this neighborhood, Community Health Partnerships, a local grassroots organization, helps the collaborating services respond to community-identified health needs, while assessing the efficacy of the collaborating services’ interventions. For example, medical students and family medicine residents surveyed neighborhood Vietnamese women to determine what concerns were a priority for them. Lack of medical interpreters and lack of support when they went into labor topped their list. This information led to the training and hiring of bilingual doulas to serve as lay birth attendants and of medical interpreters to work in the community and at University Hospital.

Also at this site, creative use of meeting space allows group visits and learning sessions. These range from a group Centering Pregnancy Class, which is coordinated and taught by a team that includes a doula, a social worker, and a family medicine resident, to a group diabetes education class conducted in Vietnamese.

Hidalgo Medical Services

Hidalgo Medical Services (HMS) is an FQHC system that colocates key services in a frontier area (one averaging fewer than 7 persons per square mile) in 7 southwest New Mexico communities. Before the system opened in 1995, the area had been without a physician for more than a decade and had never had a dentist.

HMS made its Health Commons the centerpiece of the community’s economic development strategy. This approach culminated in a comprehensive service delivery system that provides primary medical care, including hospitalization, dental care and orthodontics, behavioral health, exercise and dance classes, medication assistance, public health, and a nonprofit economic development corporation.

When the local copper mine closed, approximately 20% of the jobs and 40% of the personal income of Hidalgo County were lost overnight. In response, the HMS Board of Directors developed the Hidalgo Area Development Corporation to attract businesses to the area, create affordable housing, and support community development.

By partnering with the Department, HMS recruited 4 family medicine residency graduates to practice in these rural sites. Supporting these physicians in practice, through the Department’s innovative practice relief programs (the UNM Locum Tenens and Specialty Extension Services Programs) helps smaller communities retain these professionals.8 Historically, UNM was seen as taking patients out of the community to be cared for at its tertiary care facility. By collaborating to enhance local health resources, benefits accrue to both the community and the AHC.

Sandoval County Health Commons

The Sandoval County Health Commons is a public-private interagency partnership initiated by the Sandoval County Health Alliance. The alliance moves decision making and ownership of county health issues to the community. Bilingual staff provides interdisciplinary, holistic services through unified intake, screening, and assessment processes. Families are seen as a unit, receiving multiple services during 1 appointment in 1 building.

The integrated, on-site partners are the New Mexico Department of Health (WIC, Family Planning, and Children’s Medical Services); the Sandoval County Community Health Program (using community health workers for coordination and follow-up); and service providers for child development and parenting, domestic violence intervention, and behavioral health. Prenatal and maternity care services are being developed with UNM. Impressed with the model, the Sandoval County Commission redirected its Indigent Fund Program to finance preventive and primary health services at the Health Commons. Federal, state, and county funds were secured to build a $1.2 million Sandoval County Health Commons, which opened in 2005. This Health Commons model is being considered for replication at public health offices across the state.

RESULTS

While the 4 Health Commons have created different, locally responsive models, within several years, collaboratively they have also created “products” that better link the Health Commons sites and better serve the broader needs of the uninsured.

Information System Innovations for All Safety Net Partners

Although most safety net partners have incompatible medical information systems, they can now communicate via ExtraNet, which is a Web-based interface that is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). UNM commercialized and marketed this product for the partners. Monies generated are reinvested to expand health and social services for the uninsured. UNM has a comprehensive electronic health record, and ExtraNet improved quality of care and reduced duplication of laboratory tests and other ancillary services.

Primary Care Dispatch

CAP funded the development of a Web-based, UNM Emergency Department-housed system, called Primary Care Dispatch. This system refers uninsured, unassigned patients discharged from the emergency department to safety net and Health Commons family medicine clinics 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. With implementation of this system, the number of return visits to the emergency department was reduced by 31% among referred patients compared with control patients.12 Also, the no-show rate for emergency department follow-up visits was decreased substantially by providing unassigned patients with an appointment, a map, instructions in the appropriate language and at the proper reading level, and an assignment to a primary care clinician and a Health Commons primary care home. A local, nonprofit hospital system is purchasing the software to assign emergency department patients to primary care homes in their own system. The income generated will also be used to expand resources for the uninsured.

Community Health Workers

Community health workers are a vital, shared resource between safety net health systems and agencies within the Health Commons. One managed care organization (MCO) contracts with the consortium for $100,000 to employ community health workers to manage patients who consume a high level of resources (called Status One patients)13 among the Medicaid population. This model addresses the population of high-risk patients with comorbidities that had not been adequately addressed in the earliest model of the UNM Care Program. The Department was instrumental in securing state funding to study the contributions of community health workers to a more responsive health system and to make recommendations about how these health professionals can fit into the new model of care.

Health Advice Line

CAP partnered with the 3 MCOs in New Mexico that enroll managed care Medicaid patients in a successful effort to achieve passage by the New Mexico state legislature of a $500,000 allocation in 2005 to initiate a statewide 24-hour, nurse-run Health Advice Line. In addition, each MCO is obligated to reallocate to the in-state advice line the funds it is currently mandated to expend on telephone triage service, but that it spends through outsourcing to national call centers. This amount totals $1.2 million. The new advice line will provide all New Mexicans, especially those without insurance or an identified medical home, free professional advice to address health or social needs, and assignment to a primary care home. The board president and the medical director of the advice line are faculty members in the Department.

Service-Learning Models

The Health Commons models allow health professions students and resident trainees to get practical experience in underserved, community-based settings to balance their experience in more traditional urban, tertiary AHC venues. The Health Commons sites receive high evaluations from these learners. Data demonstrate that students and residents who have learned in these sites are 2 to 3 times more likely than other students to practice in comparable sites after graduation.4

DISCUSSION

Family medicine can play a leadership role in building collaborative approaches to seemingly intractable health problems among the uninsured, benefiting the AHC as well as the community. The AHC benefits as a creative leader in innovative service-learning models, and its research enterprise is more attractive to federal and foundation funders when the AHC can demonstrate genuine partnerships with the community.

Lessons Learned

Important lessons have been learned from New Mexico’s Health Commons sites.

Community wisdom: Priorities at each Health Commons were guided by partner and community input. Usually, the indigent and uninsured have little control over important decisions affecting their health. Yet their frontline experiences with the often harsh health system trigger creative approaches to problem solving. For example, in the Southeast Heights Health Commons, 2 family medicine residents explored options for a community-based health improvement project with unemployed Hispanic women enrolled in the clinic. To the residents’ surprise, the women’s “health” priority was finding employment; therefore, the women created the La Mesa Cleaning Cooperative. The residents came to believe that economic development was a legitimate and effective health intervention addressing the social determinants of illness presenting at their clinic.

One-stop shopping: Integrating primary care and oral, behavioral, and social services allows each member organization to better serve its clientele. Integration creates programmatic and fiscal efficiencies. Duplication is decreased, visit time is reduced, no-show rates drop, and the time required to make referrals decreases, and the efficient use of expensive clinician time is maximized.

Information systems and information technology: In a rural, poor state, access to and quality of medical care are enhanced through accessible electronic health information systems. Creating methods to quickly route unassigned emergency department patients to a primary care home can increase use of preventive services and reduce unnecessary emergency department visits and hospitalizations.

Collaboration instead of competition: Collaboration among formerly competing organizations led to unimagined innovations, attracting new private and public funding. Health Commons are appealing to funding agencies and investors and can redirect existing resources to address individual and community health needs even in the poorest, most remote locations.

Superior service-learning model: The Health Commons are the most popular clinical training sites for medical students and family medicine residents, who often become role models for local youth at risk of dropping out of school. Resident graduates prefer these sites for practice. These models double or triple the rate of retention of graduates who practice in underserved sites.4

Sustained funding: The investment in building the Health Commons sites and service, initiated with $2 million in federal funds (from the Health Resources and Services Administration’s CAP) over 4 years, led to products that are highly attractive to public and private funders. Federal, state, and county funds supported construction of the $10 million South Valley and the $1.2 million Sandoval County model Health Commons sites. State and MCO funding of $1.7 million supported development and implementation of the statewide Health Advice Line. In addition, an MCO contributed $140,000 to hire Health Commons community health workers to find “missing” high-risk Medicaid enrollees.

Economic and community development: Each Health Commons serves as an economic development zone, helping to break the poverty cycle in indigent communities, creating steady jobs that pay well, and reinvesting profits to improve access and quality.

Role of family medicine in the AHC and the nation’s health: The Department’s role in the success of the Health Commons ranged from convener, to facilitator, to fund-raiser, to technical support provider, to leader, to educator, to service provider—depending on each community’s need. A unique aspect of the model is the reshaping and deploying of resources of the AHC and of other safety net providers in the community to address those needs. AHCs sometimes fear that community engagement will saddle them with a staggering indigent burden. Yet the creation of community partnerships can facilitate a more orderly distribution of indigent patients within the community and a more predictable use of resources. The AHC’s research enterprise can benefit from the strength of family medicine’s partnerships with the community. Many National Institutes of Health requests for applications now require that AHC applicants demonstrate effective community engagement. Family medicine’s success in forging community partnerships and building health-promoting services such as the Health Commons will help AHCs’ service, education, and research missions to better address our nation’s health needs.

Next Steps

The success of the Health Commons approach has been 1 element in encouraging the UNM Health Sciences Center’s executive vice president/dean and the institutional leadership to engage in a statewide initiative in which the AHC will partner with community groups to achieve the greatest improvement in health status of any state in the nation. Key features will include replication of Health Commons models in different areas of the state and establishment of AHC-linked, community-run Cooperative Health Extension Offices to facilitate access by communities to needed AHC resources in education, service, research, and policy. The offices will be modeled on the agricultural cooperative extensions. In addition, a Community Health Report Card will be developed to measure the impact of the above interventions.

Conflicts of interest: none reported

Funding support: This work was supported in part by the US DHHS, Health Resources and Services Administration’s Healthy Community Access Program and by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s Community Voices grant (P0060131).

REFERENCES

- 1.Marmot M. The Status Syndrome: How Social Standing Affects Our Health and Longevity. New York, NY: Times Books; 2004.

- 2.Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, et al. The future of family medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(Suppl 1):S3–S32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufman A, Galbraith P, Alfero C, et al. Fostering the health of communities: a unifying mission for the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center. Acad Med. 1996;71:432–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pacheco M, Weiss D, Vaillant K, et al. The impact on rural New Mexico of a family medicine residency. Acad Med. 2005;80:739–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman A, Derksen D, McKernan S, et al. Managed care for uninsured patients at an academic health center: a case study. Acad Med. 2000;75:323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beetstra S, Derksen D, Ro M, et al. A “health commons” approach to oral health for low-income populations in a rural state. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:12–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns EA, North C, Patrick S. Serving Native American communities. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derksen D, Hickey M, Jagunich P. New Mexico’s academic model for providing practice relief for rural physicians. Acad Med. 1996;71:707–708. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi L, Starfield B, Kennedy B, Kawachi I. Income inequality, primary care, and health indicators. J Fam Pract. 1999;48:275–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufman A. Measuring social responsiveness of medical schools: a case study from New Mexico. Acad Med. 1999;74(8 Suppl):S69–S74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwack H, Sklar D, Skipper B, et al. Effect of managed care on emergency department use in an uninsured population. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murnik M, Randal F, Guevara M, Skipper B, Kaufman A. Web-based primary care referral program associated with reduced emergency department utilization. Fam Med. 2006;38:185–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forman S, Kelleher M. Status One: Breakthroughs in High Risk Population Health Management. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1999.