Abstract

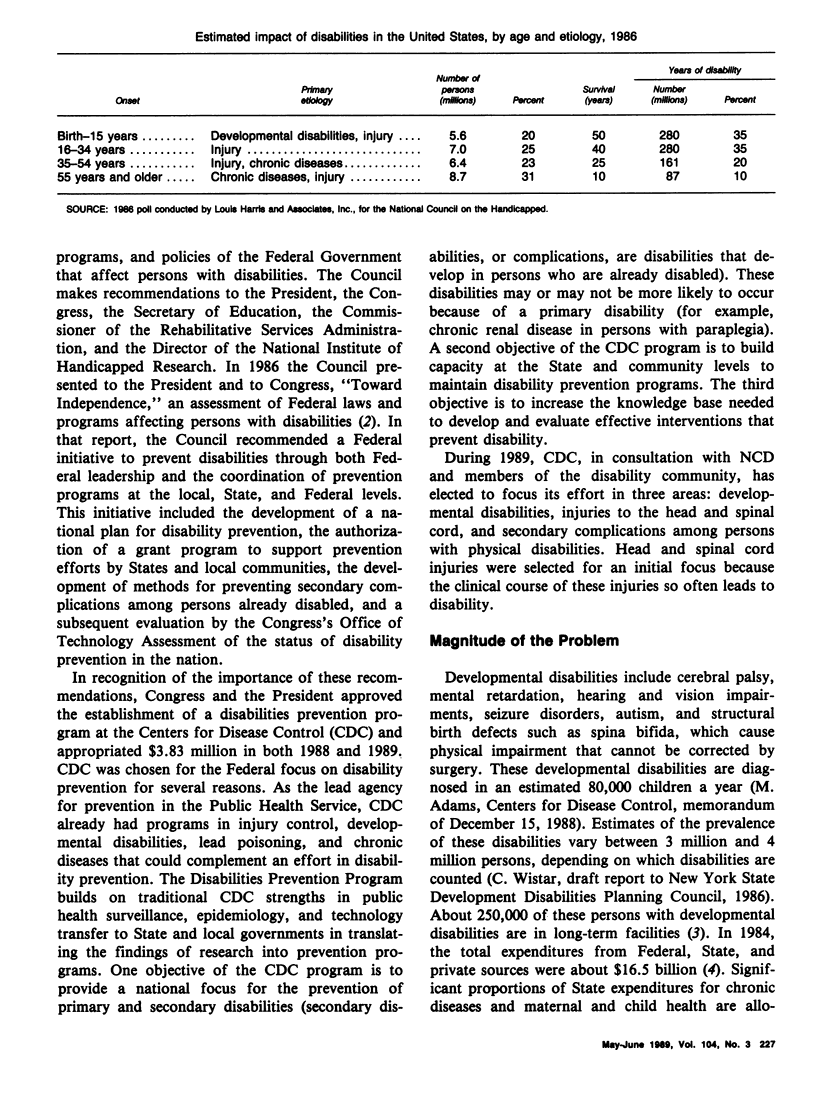

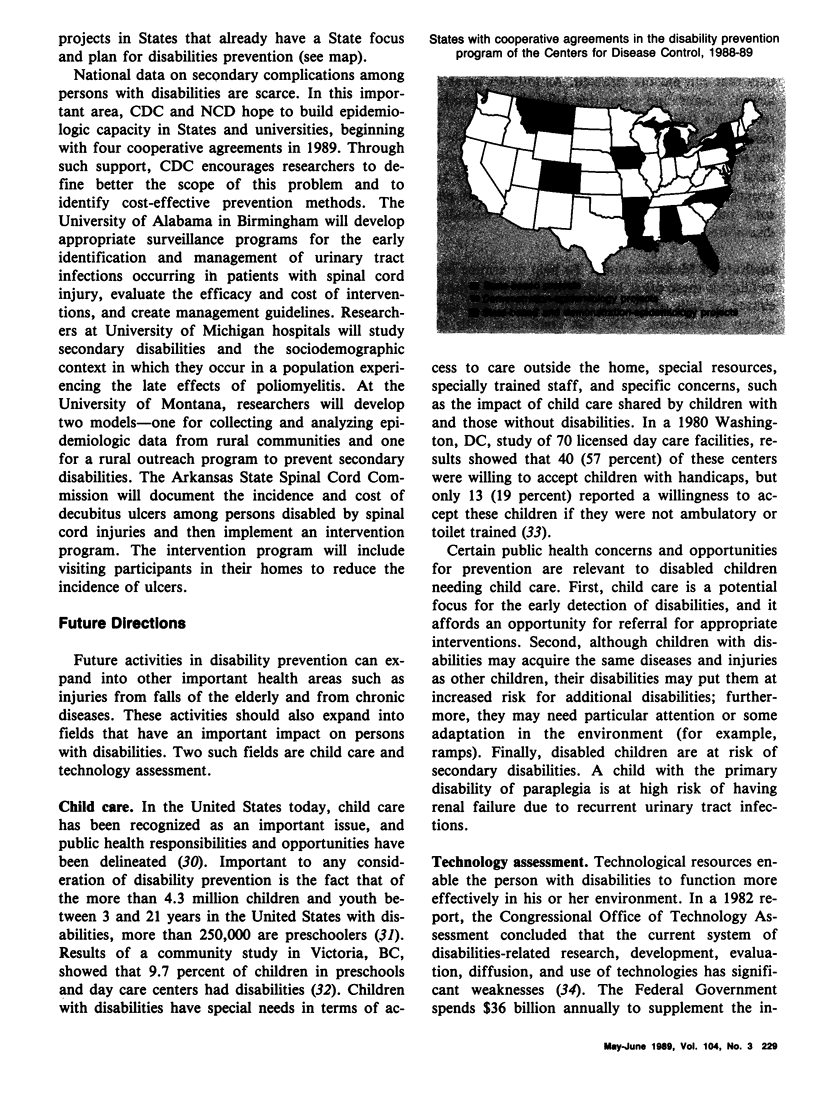

The Disabilities Prevention Program builds on traditional Centers for Disease Control (CDC) strengths in public health surveillance, epidemiology, and technology transfer to State and local governments in translating the findings of research into prevention programs. The objectives of the CDC program are to provide a national focus for the prevention of primary and secondary disabilities, build capacity at the State and community levels to maintain programs to prevent disabilities, and increase the knowledge base necessary for developing and evaluating effective preventive interventions. During 1989, CDC, in consultation with the National Council on Disabilities and members of the disability community, has elected to focus its effort in three areas: developmental disabilities, injuries to the head and spinal cord, and secondary complications among persons with physical disabilities.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Berkelman R. L., Guinan M., Thacker S. B. What is the health impact of day care attendance on infants and preschoolers? Public Health Rep. 1989 Jan-Feb;104(1):101–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braddock D., Hemp R. Governmental spending for mental retardation and developmental disabilities, 1977-1984. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1986 Jul;37(7):702–707. doi: 10.1176/ps.37.7.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caveness W. F. Incidence of craniocerebral trauma in the United States in 1976 with trend from 1970 to 1975. Adv Neurol. 1979;22:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVivo M. J., Fine P. R., Maetz H. M., Stover S. L. Prevalence of spinal cord injury: a reestimation employing life table techniques. Arch Neurol. 1980 Nov;37(11):707–708. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1980.00500600055011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson L. L., Dyson W. H. Early intervention and handicapped children in regular preschools and daycare centres. Can J Public Health. 1981 May-Jun;72(3):186–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergas Z. Spinal cord injury in the United States: a statistical update. Cent Nerv Syst Trauma. 1985 Spring;2(1):19–32. doi: 10.1089/cns.1985.2.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabow J. D., Offord K. P., Rieder M. E. The cost of head trauma in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1970-74. Am J Public Health. 1984 Jul;74(7):710–712. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.7.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin M. R., O'Fallon W. M., Opitz J. L., Kurland L. T. Mortality, survival and prevalence: traumatic spinal cord injury in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1935-1981. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38(8):643–653. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(85)90018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalsbeek W. D., McLaurin R. L., Harris B. S., 3rd, Miller J. D. The National Head and Spinal Cord Injury Survey: major findings. J Neurosurg. 1980 Nov;Suppl:S19–S31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus J. F., Black M. A., Hessol N., Ley P., Rokaw W., Sullivan C., Bowers S., Knowlton S., Marshall L. The incidence of acute brain injury and serious impairment in a defined population. Am J Epidemiol. 1984 Feb;119(2):186–201. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercy J. A., Houk V. N. Firearm injuries: a call for science. N Engl J Med. 1988 Nov 10;319(19):1283–1285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811103191911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. M., Middaugh J. P. Injuries associated with three-wheeled, all-terrain vehicles, Alaska, 1983 and 1984. JAMA. 1986 May 9;255(18):2454–2458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]