Abstract

Steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1) is an orphan nuclear receptor that is important for expression of genes involved in sexual differentiation, testicular and adrenal development, and hormone synthesis and regulation. To better understand the mechanisms required for SF-1 production, we employed transient transfec-tion analysis and electrophoretic mobility shift assays to characterize the elements and proteins required for transcriptional activity of the SF-1 proximal promoter in testicular Sertoli and Leydig cells and adrenocortical cells. Direct comparison of SF-1-promoter activity in testis and adrenal cell types established that a similar set of regulatory elements (an E box, CCAAT box, and Sp1-binding sites) is required for proximal promoter activity in these cells. Further evaluation of the E box and CCAAT box revealed a novel synergism between the two elements and iden-tified functionally important bases within the elements. Importantly, DNA/protein-binding studies uncovered new proteins interacting with the E box and CCAAT box. Thus, in addition to the previously identified USF and NF-Y proteins, newly described complexes, having migration properties that differed between Sertoli and Leydig cells, were observed bound to the E box and CCAAT box. Transient transfection analysis also identified several Sp1/Sp3-binding elements important for expression of SF-1 in the testis, one of which was previously described for expression in the adrenal gland whereas the other two were newly disclosed elements.

Keywords: gene regulation, Leydig cells, Sertoli cells, steroid hormones, testis

INTRODUCTION

The mammalian gonad originates from a bipotential pri-mordium that develops into either a testis or an ovary depending on the sex of the individual. Numerous genes that act within this developmental pathway have been identified, and many are recognized or putative transcription factors. These genes include those for Sry, steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1), Dax1, Wt1, Lim1, Emx2, Lhx9, and Sox9 [1–9]. Several of these, such as Lhx9, SF-1, and Wt1, have been shown to participate in early steps of gonadogenesis. Null mutations in any of these caused a block in formation of the genital ridge, whereas later steps in gonad formation and sex determination are thought to be regulated by Sry, Sox9, and Dax-1 [1, 3, 7, 9–11]. However, despite progress in identifying several key genes involved in gonad development and sex determination, the mechanisms that control their expression and the regulatory network that links them within this pathway are poorly understood.

Also known as adrenal-4-binding protein, SF-1 is an orphan nuclear receptor that is expressed from one of several transcripts generated from the Ftz-F1 gene [12, 13]. Its central role as a developmental regulator was revealed by the numerous defects (sex reversal, adrenal deficiency, and gonadal agenesis) associated with mutations within the Ftz-F1 gene [10, 14–16]. The expression profile of SF-1 supports its role in the gonads and adrenals, where it is first observed in an embryonic cell population destined for adrenal glands and gonads, and its expression is maintained throughout development in these organs [17, 18]. In the gonads, SF-1 is expressed in both the supporting cells (Ser-toli and granulosa cells) and the steroidogenic cells (Ley-dig, granulosa, and theca cells). In addition, SF-1 has been shown to be a key transcriptional regulator of genes involved in steroid hormone and gonadotropin biosynthesis [13, 19–31]. Its role in endocrine function is further supported by the presence of SF-1 in the hormone-producing cells of the adrenal gland, gonad, and anterior pituitary [32–36].

Because of SF-1’s critical role in development and endocrine regulation, identification of the molecular mechanisms that control SF-1 expression will help to elucidate the underlying transcriptional events that govern differentiation and development of the gonads and adrenals as well as provide clues regarding the mechanisms involved in endocrine homeostasis and hormone biosynthesis. Studies to date have focused on the identification of elements and proteins that regulate SF-1 transcription through its proximal promoter region and have provided insight regarding SF-1 expression. Collectively, studies have examined basal promoter activity of SF-1 in cells derived from the adrenal gland (Y1 adrenocortical), pituitary (αT3 gonadotrope), and testis (MA-10 Leydig and MSC-1 Sertoli) and, through deletion analysis, have revealed that basal transcription is predominately regulated by sequences within the first 110 base pairs (bp) of the promoter, a region that is highly conserved among different species (Fig. 1A) [37–40]. Studies of the proximal promoter region have identified important elements within the proximal region, including an E box, a CCAAT box, and an Sp1 site (Fig. 1A) [37–40]. In addition, Shen and Ingraham [41] recently identified a Sox9-binding site that is important for activity of the mouse SF-1 promoter [41]. In each cell type investigated, functional requirement for the E box has been established, and some of the E box-bound proteins have cross-reacted with antibodies generated against the basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper (bHLH-ZIP) proteins upstream stimulatory factor (USF) 1 and USF2 [37–40]. The CCAAT box was shown to contribute to SF-1-promoter activity in Y1, MA-10, and Sertoli cells, but only in Y1 cells has a protein interacting with this element been characterized [38]. In Y1 cells, Woodson et al. identified the CCAAT-binding factor NF-Y as binding this important element [38]. In testicular Sertoli and Leydig cells, specific complexes were observed to bind this element, some of which not only required the CCAAT box sequences for optimal binding but sequences within the nearby E box as well [37]. Lastly, a third element, located approximately 25 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site, was shown to contribute to SF-1-promoter activity in Y1 cells and to bind to the transcription factor Sp1 [38]. To our knowledge, no role for this element has been reported in other SF-1-expressing cell types.

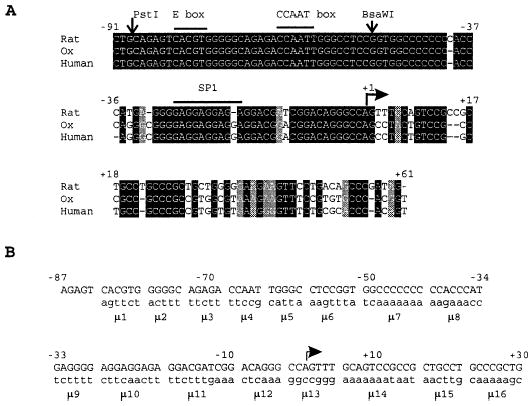

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the nucleotide sequence of the 5′ flanking regions of SF-1 genes and block-replacement mutants. A) Nucleotide sequences of the proximal promoter and 5′ untranslated region of the SF-1 genes compared between rat (GenBank accession no. D42151), ox (GenBank accession no. AF140357), and human (GenBank accession no. D84206). Numbers indicate the position of the nucleotides in the rat SF-1 gene (−91 to +61) relative to the major transcription start site (+1 indicated by an arrow). Nucleotides identical between the three sequences are dark shaded, similar are light shaded, and the nucleotide deletions (alignment gaps) are indicated by dashes. The Sox9, E box, CCAAT box, and Sp1 regulatory elements are also given. The PstI and BsaWI restriction sites used for the generation of the mutants are marked (see Materials and Methods). B) Sequences of the block-replacement mutations generated within the region spanning −87 and +30 of the rat SF-1 gene. The wild-type sequence of the rat gene (regions 1–16) is presented on the top strand in uppercase letters. The positions and sequences of the block-replacement mutants (μ1 through μ16) are shown on the bottom strand in low-ercase letters.

In the present study, we further evaluated the base requirements and binding complexes for the E box and CCAAT box in testicular Sertoli and Leydig cells, characterized the role of the USF proteins in promoter function, and evaluated the synergistic interactions between the proteins binding the E box and CCAAT box elements. In addition, extensive block-replacement mutagenesis was used to complete the analysis of the proximal promoter. Two new elements, located downstream of the transcription start sites, were identified and shown to bind the transcription factors Sp1, Sp2, and Sp3. Finally, we observed that the various functionally relevant elements are differentially bound by factors in Sertoli and Leydig cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Lipofectamine, Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM), horse serum, fetal bovine serum, penicillin, streptomycin, and Waymouth media were purchased from Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD). Restriction enzymes, Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System, and DNA Polymerases were from Life Technologies or Promega (Madison, WI). Polynucleotide kinase was a product of New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Poly(dIdC) and the ribonucleotides were purchased from Pharmacia (Piscataway, NJ) and Dupont NEN (Boston, MA), respectively. Antibodies against USF1, USF2, Wt1, Egr1, Sp1, Sp2, Sp3, Sp4, Coup TFII, E47, E2A, and Myc were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The antibody for the A subunit of NF-Y was purchased from Rockland, Inc. (Gilbertsville, PA). Oligodeoxynucleotides were purchased from Genosys (The Woodlands, TX) or from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA).

DNA Constructs

Expression vectors for the murine USF proteins were provided by Dr. Michelle Sawadogo as described elsewhere [42, 43]. Construction of the wild-type reporter constructs SF1(−734/+60)Luc and SF1(−734/+10)Luc and the block-replacement mutants μ1 through μ4 were published previously [37]. Mutagenesis of the rat SF-1 proximal promoter was performed using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based strategy as described elsewhere [37, 44, 45]. Unless otherwise indicated, the template was reporter plasmid SF1(−734/+60)Luc. Sequences of the mutant oligodeoxynucleo-tides are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Structures of mutagenic oligonucleotides.

| Mutanta | Oligonucleotideb |

|---|---|

| μ7 | GGCCTCCGGTTCAAAAAAACCACCCATG (F) |

| μ8 | GGGCCTCCGGTGGCCCCCCCAAGAAACCGAGGGGA (F) |

| μ9 | GGGCCTCCGGTGGCCCCCCCCCACCCATTCTTTTAGGAGG (F) |

| μ10 | GGGCCTCCGGTGGCCCCCCCCCACCCATGAGGGGCTTC (F) |

| μ11 | GGGCCTCCGGTGGCCCCCCCCCACCCATGAGGGGAGGA (F) |

| μ10.1 | GGGCCTCCGGTGGCCCCCCCCACCCATGAGGGGAGGCGGAGAGGACGATCGGACAGG (F) |

| μ12 | GGGGGAAGCTTCAGCGGGCAGGCAGCGGCGGACTGC AAACTGGTTTGAGCCGATCGTCC (R) |

| μ13 | BBBBBAAGCTTCAGCGGGCAGGCAG CGGCGGACTGCCCCGGCCCCCTGTCCGATCGTCC (R) |

| μ14 | GGGGGAAGCTTCAGC GGGCAGGCAGATTATTTTTTTAAACTGGCCCTGTCCG (R) |

| μ15 | GGGGGAAGCTT CAGCGGGCCAAGTTCGGCGGACTGCAAACTGG (R) |

| μ16 | GGGGGAAGCTTGCTTT TTGAGGCAGCGGCGGACTGC (R) |

| μ1.1 | AAAGGCCTGCAGAGTCAGCTGGGGGCAGAGACC (F) |

| μ1.2 | AAAGGCCTGCAGATACACGTGTAGGCAGAGACC (F) |

| μ1.3 | AAAGGCCTGCAGAGTCACATGGGGGCAGAGACC (F) |

| μ1.4 | AAAGGCCTGCAGAGTAACGTGGGGGCAGAGACC (F) |

| μ1.5 | AAAGGCCTGCAGAGTCAGATGGGGGCAGAGACC (F) |

| μ3.1 | AAGGCCTGCAGAGTCACGTGGGGGCTCTGACCAATTGGGCCTCCGGTGGCCCCCC (F) |

| μ3.2 | AAGGCCTGCAGAGTCACGTGGGGGCAGACTCCAATTGGGCCTCCGGTGGCCCCCC (F) |

| μ4.1 | AAGGCCTGCAGAGTCACGTGGGGGCAGAGAGGAATTGGGCCTCCGGTGGCCCCC (F) |

| μ4.2 | AAGGCCTGCAGAGTCACGTGGGGGCAGAGACCAAATGGGCCTCCGGTGGCCCCCC (F) |

| μC | AAGGCCTGCAGAGTCACGTGGGGGCTTCTTTTCCGTGGGCCTCCGGTGGC (F) |

| Ins3 | AAGGCCTGCAGAGTCACGTGGGAGAGGCAGAGACCAATTGGGC (F) |

| Ins5 | AAGGCCTGCAGAGTCACGTGGGAGAGAGGCAGAGACCAATTGGGC (F) |

| Ins7 | AAGGCCTGCAGAGTCACGTGGGAGAGAGAGGCAGAGACCAATTGGGC (F) |

| Ins10 | AAGGCCTGCAGAGTCACGTGGGAGAGAGACCTGGCAGAGACCAATTGGGC (F) |

| Ins15 | AAGGCCTGCAGAGTCACGTGGGAGAGAGACCTAGAGAGGCAGAGACCAATTGGGC (F) |

| Ins20 | AAGGCCTGCAGAGTCACGTGGGAGAGAGACCTAGAGAGACCTGGCAGAGACCAATTGGGC (F) |

| 3′Ins20 | AAGGCCTGCAGAGTCACGTGGGGGCAGAGACCAATAGAGAGACCTAGAGAGACCTTGGGCCTCCGGTGGCC (F) |

| μ1/μC | AAGGCCTGCAGAGTAGTTCTGGGGCTTCTTTTCCGT (F) |

| +49 | GGGGAAGCTTCAGGAACTTCTTCCCCCAGC (F) |

| +30 | GGGGAAGCTTCAGC GGGCAGGAGCGGC (F) |

Sequences of complementary oligonucleotides and specifics of mutant generation given in Materials and Methods.

All PCR oligonucleotides presented 5′ to 3′ together with their respective orientations. F, Forward; R, reverse.

For the block-replacement mutants μ7 through μ11, two PCR reactions were carried out. The first amplification fragment was obtained by using the upstream primer 5′-GGGGCTCGAGGAAGAGTGAAA-3′ (located upstream of the naturally occurring PstI site of the SF-1 promoter at position −87) and downstream primer 5′-GGGGAAGCTTCTATCGGGCTG-TCAGGAACT-3′ (with a HindIII site introduced into the 5′ end of the primer). This PCR product was subsequently digested with PstI and BsaWI (located at position −52) and gel-purified. The second PCR product was produced using a forward primer carrying the desired mutation (harboring the BsaWI site at position −52) and the reverse primer described above. The following forward primers were used: μ7, μ8, μ9, μ10, and μ11 (Table 1). The corresponding amplification products were later digested by BsaWI and HindIII. Finally, the restriction fragments PstI/BsaWI and BsaWI/HindIII were directionally ligated into the PstI/HindIII sites of a SF1(−734/+60)Luc vector. The point mutant of region 10 was likewise generated with the mutant primer μ10.1.

Block-replacement mutants μ12 through μ16 were obtained by sub-cloning a single PCR fragment carrying the given mutations into the PstI/HindIII sites of the SF1(−734/+60)Luc vector. The PCR products were amplified by using the forward primer 5′-GGGGCTCGAGGAAGAGT-GAAAAAAGATATAGACC-3′ (binding at position −153) and reverse primers harboring the desired substitutions. The five reverse primers were μ12, μ13, μ14, μ15, and μ16 (Table 1). The PCR fragments were digested by PstI and HindIII and ligated into the PstI/HindIII sites of SF1(−734/+60)Luc. Note that these downstream primers all end at position +30, making SF1(−734/+30)Luc, not SF1(−734/+60)Luc, the wild-type reporter construct for mutants μ12 through μ16.

To construct point mutants of the E box (μ1.1 through μ1.5), CCAAT box (μ3.1 through μ4.2), and the block-replacement mutant μC, single PCR reactions were performed using a specific forward primer (binding to position −87 and, thus, having the PstI site) and the oligodeoxynucleotide 5′-GGGGAAGCTTCTATCGGGCTGTCAGGAACT-3′ (HindIII site at position +60) as reverse primer. The fragments containing insertions within the region encompassing the E box and CCAAT box were amplified by PCR using a forward primer containing the desired mutation (PstI site at position −87) and the reverse primer 5′-GGGGAAGCTTCTATCGG-GCTGTCAGGAACT-3′ (HindIII site at position +60). The forward oligodeoxynucleotides were Ins3, Ins5, Ins7, Ins10, Ins15, Ins20, and 3′Ins20, respectively (Table 1). Amplified DNA products were digested with PstI/HindIII and cloned into the corresponding sites of SF1(−734/+60)Luc. The double-mutant μ1/μC was similarly generated using reporter plasmid μC as template, upstream mutagenic primer μ1/μC, and downstream primer 5′-GGGGAAGCTTCTATCGGGCTGTCAGGAACT-3′. The 3′-deletion mutants of the SF-1 proximal promoter were prepared by PCR using SF1(−734/+60)Luc as template, the forward primer 5′-GGGGCTCGA-GATCCGTCTAGGCCAGTTCAG-3′ (XhoI site at position −734), and downstream primers that terminated at position +49 or +30 (Table 1).

The XhoI/HindIII fragments of the PCR reactions were subcloned into the analogous sites of plasmid pGL3-Basic. Plasmid DNAs were prepared from overnight bacterial cultures using DNA plasmid purification columns according to the supplier’s recommendations (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). All the clones were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis using the ABI-Prism dRhodamine Terminator Cycle Sequence Ready Reaction Kit (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Cell Culture and Transient Transfection Analysis

Preparation of primary rat Sertoli cells, growth conditions for mouse MA-10 Leydig cells and mouse MSC-1 Sertoli cells, and transient transfection methods have been described elsewhere [37]. Y1 cells, a mouse adrenocortical tumor cell line, were cultured in Ham F10 medium supplemented with 15% (v/v) horse serum, 2.5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, and 2 mM L-glutamine in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 (v/v) at 37°C. Cells were split a day before transfection and plated in 2.5-cm wells at a density of 52 000 cells/well. The next day, cells were transfected with 0.2 μg of firefly luciferase reporter vector, 10 ng of pRL-TK, and 1 μl of lipofectamine in DMEM. After 15–20 h of incubation in the presence of the lipid/DNA mixture, the culture medium was replaced by fresh growth medium. Seventy-two hours after transfection, all cell lines were harvested and the lysates analyzed for firefly and Renilla luciferase activities with the Dual-Luciferase kit in a MLX Microtiter Plate Luminometer (Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA). Transfection data were reported as the fire-fly/Renilla luciferase activity of each construct normalized to the firefly/Renilla luciferase activity of either wild-type SF1(−734/+60)Luc or SF1(−734/+30)Luc. Reported values were an average of at least three independent experiments and included a minimum of two independent clones for each data set. To study the effect of the USF proteins (USF1/USF2) or their deletion mutants (U1ΔN/U2ΔN), cotransfections of MSC-1 cells were done with 150 ng of the luciferase reporter construct, 10 ng of plasmid pRL-TK, and various amounts of expression vector (range, 50–200 ng). Constant DNA levels were maintained in each transfection by including the needed amount of empty expression vector pSG5. In the case of MA-10 cells, cotransfections were performed with 150 ng of reporter construct, 10 ng of pRL-TK, and 25, 50, 100, or 150 ng of expression vector for the various USF proteins. In these studies, the firefly/Renilla luciferase values generated in the presence of cotransfected expression vector were normalized to the firefly/Renilla values of wild-type SF1(−734/+60)Luc transfected in the presence of 200 or 150 ng of empty vector pSG5. All investigations involving animals were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-sample Student t-test (two-tailed) assuming unequal variance (P < 0.01).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

Nuclear extracts were prepared as previously described [37]. Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL) using bovine serum albumin as a standard. For electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs), complementary single-strand oligodeoxynucleotides were annealed and then end-labeled using [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase. The oligodeoxynucleotides used for EMSA are described in Table 2. Binding reactions were performed at a final volume of 20 μl in buffer (10 mM Hepes [pH 7.9], 30 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 12% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.2 mM PMSF, and 10 μM ZnCl2) containing 20 ng of BSA, 500 ng of poly(dIdC), and 100 ng of salmon sperm DNA. Reaction mixtures were preincubated for 10 min on ice in the presence of 10 μg of nuclear extract, followed by the inclusion of 25 fmol of radiolabeled probe (~10 000 cpm/fmol). A 36-bp nonspecific oligodeoxynucleotide was included to confirm specific complexes (Table 2). After further incubation on ice for 30 min, the DNA-protein complexes were resolved at 4°C by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (acrylamide:bis-acrylamide, 19:1 [w/w]) in 25 mM Tris, 190 mM glycine, and 0.5 mM EDTA. The gels were run at 240 V for 1.25 h, dried, and analyzed by autoradiography. For competition experiments, competitor oligodeoxynucleotides were included at the preincubation step at the fold molar excess indicated in the legend of the figures. Antibody supershift assays were carried out by adding antibodies to the reaction mixture before the addition of labeled probe. One microliter of antibody was used, except where otherwise indicated.

TABLE 2.

Sequences of oligodeoxynucleotides used for EMSA.

| Oligodeoxynucleotide (position)a | Sequenceb |

|---|---|

| E/C (−90 to −55) | TGCAGAGT CACGTG GGGGC AGAGACCAAT TGGGCCT |

| μE/C (−90 to −55) | TGCAGAGT agttct GGGGC AGAGACCAAT TGGGCCT |

| E/μ2/C (−90 to −55) | TGCAGAGT CACGTG acttt AGAGACCAAT TGGGCCT |

| E/μC (−90 to −55) | TGCAGAGT CACGTG GGGGC ttcttttccg TGGGCCT |

| E box (−94 to −65) | GGCC TGCAGAGT CACGTG GGGGC AGAGACC |

| μ1.1/C (−90 to −55) | TGCAGAGTCAgcTGGGGGCAGAGACCAATTGGGCCT |

| μ1.3/C (−90 to −55) | TGCAGAGTCACaTGGGGGCAGAGACCAATTGGGCCT |

| μ4.1 (−90 to −55) | TGCAGAGT CACGTG GGGGC AGAGAggAAT TGGGCCT |

| μ4.2 (−90 to −55) | TGCAGAGT CACGTG GGGGC AGAGACCAAa TGGGCCT |

| CCAAT box (−73 to −54) | GC AGAGACCAAT TGGGCCTC |

| C/EBP | TGCAGATTGCGCAATCTGCA |

| NF-Y | GAGACCGTACGTGATTGGTTAATCTCTT |

| Sp1 | ATTCGATCGGGGCGGGGCGAGC |

| Egr1 | GGGAGTCAGTCTTGCGTGGGCGTTAGTCAGTCGGG |

| NS | CTAGAGTCGACCTGCAGGCATGCAAGCTTGGCATTC |

| 9/10 (−41 to −6) | CCACCCATGAGGGGAGGAGGAGAGGACGATCGGACA |

| μ9/10 (−41 to −6) | CCACCCATtcttttAGGAGGAGAGGACGATCGGACA |

| 9/μ10 (−41 to −6) | CCACCATGAGGGGcttcaacttGGACCATCGGACA |

| 14 (−5 to +25) | GGGCCAGTTTGCAGTCCGCCGCTGCCTGCC |

| μ14 (−5 to +25) | GGGCCAGTTTaaaaaaataatCTGCCTGCC |

| 16 (+8 to +40) | AGTCCGCCGCTGCCTGCCCGCTGCTGGGGGAAGTTGTT |

| μ16 (+8 to +40) | AGTCCGCCGCTGCCTcaaaaagcCTGGGGGAAGTTGTT |

Positions given relative to the major transcriptional start site at +1, based on the rat SF-1 promoter sequence (see Fig. 1A).

EMSA oligonucleotides shown as sense strand with mutations in bold. Lowercase letters represent bases altered from the wild-type sequence.

RESULTS

Several Protein Complexes Bind to the E Box and CCAAT Box in Testicular Cells

To delineate the elements required for SF-1 expression, a series of 16 block-replacement mutations were generated between −87 and +30 in the rat SF-1 promoter. Initial studies characterized mutations μ1 through μ6 in testicular Leydig and Sertoli cells, identifying an E box and CCAAT box (Fig. 1B, μ1, μ3, and μ4) as important for promoter function [37]. Studies also revealed three major protein complexes that specifically bound a probe containing both the E box and CCAAT box when using extracts derived from Leydig or Sertoli cells (Table 2, E/C probe, and Fig. 2) [37]. As presented here, subsequent characterization revealed that some complexes within bands 1 and 3 depended on sequences within the intervening region (region 2) of the two elements, because these complexes were not competed by an oligodeoxynucleotide containing a mutation in this region (Fig. 2, E/μ2/C). Because the intervening region (region 2) did not have associated functional activity [37] yet was important for several of the binding complexes, it was important to better resolve the complexes to identify the relevant transcriptional regulators.

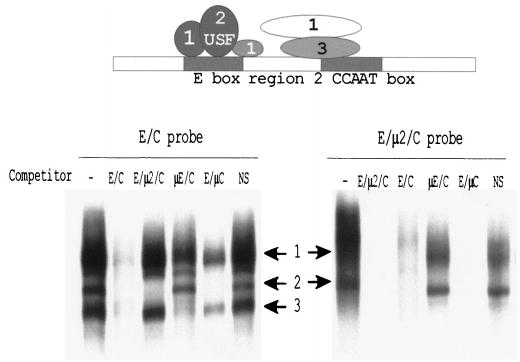

FIG. 2.

The region encompassing the E box and CCAAT box elements of the SF-1 promoter binds several protein complexes. EMSAs were performed with either the E/C or the E/μ2/C probe together with nuclear proteins from MA-10 cells, and 25 fmol of radiolabeled probe were used together with 10 μg of a whole-cell nuclear extract prepared from MA-10 cells as described in Materials and Methods. Where indicated, 150-fold molar excess of competitor was added to the reactions. Sequences of probes and competitors are given in Table 2. The numbered arrows indicate the positions of the three major specific complexes that bind the probes. The diagram above is a schematic representation of the protein complexes that interact with this region of the promoter. The positioning of the putative factors is based on their respective base requirements, but the depicted contacts between complexes are not intended to represent interactions. The identity of the factors constituting complex 2 (USF) was established previously. Note that block replacement of region 2 showed that this region does not contribute to basal transcription [37].

Using competitors containing mutations in different elements, EMSA revealed that the three major bands bound to the wild-type E/C probe represented distinct complexes with different binding requirements (Fig. 2, top). Band 1 contained several complexes, some of which were not competed by oligodeoxynucleotides that contained mutations in either the E box, region 2, or the CCAAT box, identifying proteins that bound only the E box, that bound the E box and region 2, and that bound the CCAAT box and region 2. Band 2 required only sequences within the E box, and band 3 bound region 2 and the CCAAT box. The latter complex was only competed by oligodeoxynucleotides having both an intact region 2 and CCAAT box (Fig. 2, E/C, μE/C, and E/μC).

Because proteins bound to the intervening region 2 appeared to obscure detection of relevant E box and CCAAT box complexes, EMSAs were performed using smaller probes that better restricted the sequences to the E box or CCAAT box (Table 2). Two specific complexes were observed to bind the E box probe when extracts derived from either Sertoli cells or MA-10 cells were employed (Fig. 3A, arrows). An oligodeoxynucleotide containing a mutation in the E box failed to compete with the complexes in either cell type, whereas oligodeoxynucleotides containing mutations in region 2 (E/μ2/C) or the CCAAT box (E/μC) successfully competed with the complexes. Thus, the observed complexes required sequences within the E box, but not region 2 or the CCAAT box, for binding.

FIG. 3.

The transcription factors USF and NF-Y, in addition to unidentified proteins, bind to the E box and CCAAT box in testicular cells. EMSAs were performed by incubating the radiolabeled E box probe (A) or CCAAT box probe (B) with nuclear proteins from MA-10 and primary Sertoli cells as described in Figure 2. Where indicated, competitors were added at a 100-fold molar excess for reactions with the E box and a 200-fold molar excess for reactions with the CCAAT box. For antibody supershift analysis, antibodies (Ab) specific for the transcription factors USF1, USF2, Myc, and NF-Y were added to the binding reactions before addition of the probes. The sequences of the oligodeoxynucleotides are given in Table 2. The major specific complexes are marked with arrows, and the super-shifted complexes are indicated by asterisks to the left of the lanes.

As previously observed, USF1 and USF2 are components of complexes in each cell type, as shown by the ability of antibodies to cross-react with proteins within the shifted complexes (Fig. 3A) [37]. The supershift analysis also indicated that USF1 is a component of all the complexes in one band whereas USF2 is a minor constituent. Interestingly, complexes that differed between the two cells that did not contain the USF proteins were also observed, as indicated by the lack of cross-reactivity to the antibodies. In Sertoli cells, this complex migrated faster than the USF-containing complex, whereas in MA-10 cells, it migrated more slowly (Fig. 3A). Antibodies against other potential binding factors, including E47, Myc, E2A, COUP-TFII (chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor II), and SREBP (sterol regulatory element binding proteins), failed to cross-react with the non-USF-containing complexes (Fig. 3A and data not shown). Thus, these studies identified proteins other than USF1 and USF2 that are candidates for transcriptional regulators of SF-1 through the E box.

Nuclear proteins from either Sertoli or MA-10 cells produced two specific protein-DNA complexes when incubated with an oligodeoxynucleotide containing the CCAAT box (Fig. 3B, arrows). Homologous competitor specifically disrupted these complexes, and no effect was observed with a nonspecific sequence. Specific complexes in each cell type were competed by a consensus NF-Y-binding site, whereas only one of the complexes was lost with the addition of a C/EBP consensus element. In both Sertoli and MA-10 cells, one of the binding complexes cross-reacted with an antibody generated to the transcription factor NF-Y, because inclusion of the antibody resulted in a loss of this band and the formation of a supershifted complex (Fig. 3B, asterisks). In addition to the NF-Y consensus sequence, the second specific complex was also competed with an oligodeoxynucleotide containing the consensus C/EBP site. However, additional studies using the C/EBP oligodeoxynucleotide as a probe revealed that the SF-1 CCAAT box was unable to compete the C/EBP complexes bound to this element, even at a 1000-fold molar excess (data not shown), suggesting that C/EBP is not the second factor binding the SF-1 CCAAT box. Therefore, the ubiquitous factor NF-Y as well as other unidentified proteins interact with the SF- 1 CCAAT box in the gonads.

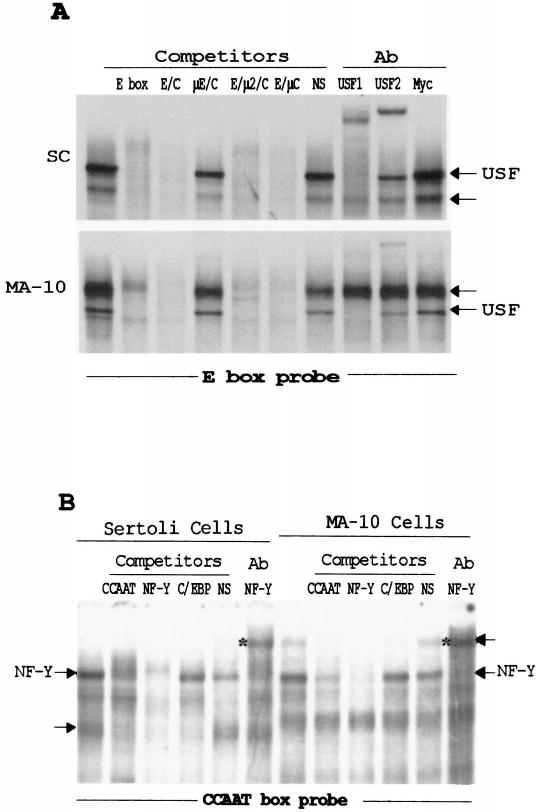

E Box Function Requires Bases Within the Element’s Core and Flanking Region

The above studies implicated two distinct complexes in the regulation of the SF-1 promoter through the E box. The USF proteins formed one of these complexes, whereas the other remained elusive. Based on these findings, we refined our analysis of this key regulatory element by designing a series of more subtle mutations of this motif. The promoter activities of five point mutants of the E box and flanking bases, together with the capacity of some of these sequences to bind nuclear proteins, were examined (Fig. 4). Transient transfection analysis of promoter/reporter constructs was performed in three different SF-1-expressing cell types: Sertoli (primary and MSC-1), Leydig (MA-10), and adrenocortical (Y1) cells. Examination of promoters carrying mutations μ 1.1 (CACGTG to CAgcTG) and μ 1.5 (CACGTG to CAgaTG) revealed that the central two bases of the E box are critical to its function, because promoter activity was abrogated to nearly the same extent as with the full block-replacement mutation (Fig. 4A, compare to μ 1). A similar impact was observed with a mutation in the first base of the core sequence (μ 1.4, CACGTG to a-ACGTG) or in the bases immediately flanking the element (μ 1.2, GTCACGTGGG to taCACGTGta). A more modest impact on promoter activity was observed with a guanine-to-adenine change in the fourth position of the core (Fig. 4A, μ 1.3). Between the four cell types, the overall trends were similar, but subtle differences were observed in the overall impact of specific base mutations. In general, mutations in the E box had a greater impact in primary Sertoli cells and less of an impact in Y1 cells.

FIG. 4.

Point mutations in the E box reveal bases within the core and flanking sequences that are needed for its function. A) Five single- or double-base substitutions of the E box were generated in the context of the SF1(− 734/+60)Luc reporter plasmid. The constructs were transiently transfected into MA-10, MSC-1, primary Sertoli cells, and Y1 cells, and their activities were determined by the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay (see Materials and Methods). All transfections were performed in the presence of pRL-TK (Renilla luciferase expressed from the viral thymidine kinase promoter), which was used as a control for transfection efficiency. The relative activity represents the average firefly/Renilla luciferase values of each mutant relative to the firefly/Renilla luciferase activity of the wild-type SF1(− 734/+60)Luc construct. Data represent a minimum of three independent transfections for each cell type. Error bars represent the SEM. Sequences of the mutants from positions − 87 to− 72 are shown at the bottom. The E boxes are underlined, and bold lettering indicates the mutated nucleotides. Asterisks indicate values that are statistically different from those of mutant μ 1 for each cell type according to the Student t-test (assuming unequal variance with P < 0.01). B) EMSA was performed using a radiolabeled E box probe together with nuclear proteins extracted from primary Sertoli cells and MA-10 cells as described in Figure 2. To determine the relative affinities of the retarded E box complexes, a 5-, 10-, and 25-fold molar excess of various competitors (indicated above the lanes) was added to the binding reaction. The structures of the E box probe and competitor oligodeoxynucleotides used are given in Table 2. Arrows indicate positions of two specific complexes.

Mutations μ 1.1 and μ 1.3, which differentially influenced promoter activity, were tested for their impact on the E box-binding complexes by examining the ability of the mutated oligodeoxynucleotides to compete for the binding factors. In Sertoli cells, oligodeoxynucleotides containing either the μ 1.1 or μ 1.3 mutation competed with both complexes less effectively than the wild-type sequence (E/C), indicating that they partially disrupted binding of the complexes (Fig. 4B, top). In accordance with their impact on promoter activity, μ 1.3 more effectively competed for the complexes and, thus, bound them with higher affinity than did μ 1.1. In MA-10 cells, the effects of the μ 1.1 and μ 1.3 mutations on USF binding were less apparent, because their competition profiles were similar to that observed for the wild-type sequence (Fig. 4B, bottom, E/C). However, with each mutation, a clear diminution in binding affinity was observed for the upper complex (Fig. 4B, bottom). Consistent with the effects observed on promoter activity, the μ 1.3 mutation more effectively bound the upper complex than did the μ 1.1 mutation. The binding data therefore implicate the upper E box-binding complex in basal SF-1 transcription in MA-10 cells and either complex in Sertoli cells.

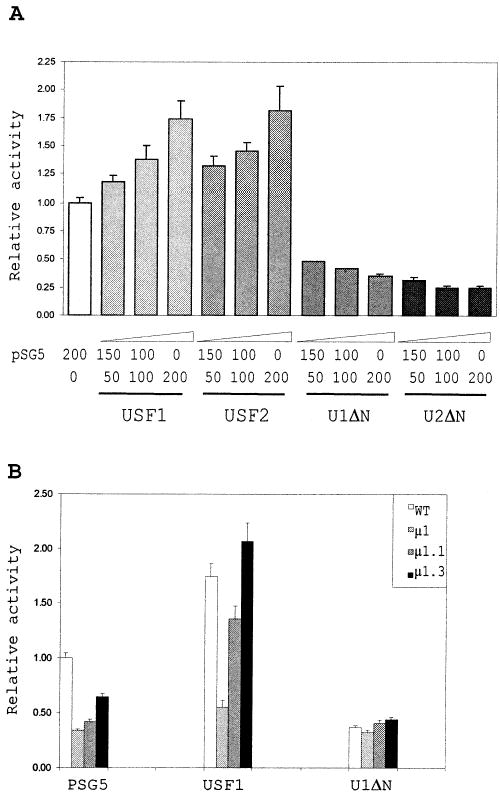

USF Proteins Transactivate the SF-1 Promoter Through the E Box

Because the USF proteins were observed to bind the SF-1 E box in EMSA, we tested whether these proteins were able to transactivate the SF-1 promoter through this element. In the mouse Sertoli cell line MSC-1, cotransfection of the SF-1 promoter with expression vectors that produce wild-type USF1 or USF2 resulted in a moderate, dose-dependent increase in transcriptional activity (Fig. 5A). This weak dose response is probably caused by the presence of high levels of endogenously expressed USF proteins in MSC-1 cells [42]. In contrast, cotransfection with dominant-negative forms of USF1 and USF2 that lack the amino-terminal transactivation domain (U1ΔN and U2ΔN) [43] caused a dramatic decrease in promoter function and, hence, suggests USF transactivation (Fig. 5A). Importantly, similar changes were not observed on a second reporter construct containing the SV40 promoter, demonstrating that the effects were specific to the SF-1 promoter (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

USF1 transactivates the SF-1 promoter through the E box. A) Cotransfection of MSC-1 cells with the wild-type SF-1 promoter and expression vectors for the USF proteins. The wild-type SF1(− 734/+60)Luc reporter construct (150 ng) was transiently transfected into MSC-1 cells together with a constant amount (200 ng) of empty vector (pSG5) plus USF expression vector and 10 ng of pRL-TK, a control plasmid for trans-fection efficiency (see Materials and Methods). Transactivation of the SF-1 promoter was analyzed using increasing amounts of expression vector (50–200 ng) either for the wild-type USF proteins (USF1 and USF2) or for their N-terminal deletion mutants (U1ΔN and U2ΔN). Activities are expressed relative to the activity of the wild-type SF1(− 734/+60)Luc trans-fected with 200 ng of empty vector alone. B) Cotransfection of MSC-1 cells with promoter E box mutants and expression vectors for USF1 and U1ΔN. The cotransfection experiment was performed with 200 ng of expression vector as described in A, except that E-box mutant promoters (μ 1, μ 1.1, and μ 1.3) were used as reporter constructs. The sequences of the E boxes are as described in Figure 3. Error bars represent the SEM, and data represent a minimum of three independent experiments.

Cotransfection of the USF proteins with SF-1 promoters housing different mutations in the E box showed that an intact element was needed for overexpressed USF1 to stimulate promoter activity (Fig. 5B). Thus, activity of a promoter containing a complete block-replacement mutation through the E box (μ 1) was not altered when cotransfected with the wild-type USF1 or U1ΔN expression vector. In contrast, the USF2 expression vector stimulated promoter activity in the absence of the core E box sequence, indicating that USF2 activation was not specific for the element (data not shown). Consistent with the data demonstrating USF1 binding to the μ 1.1 and μ 1.3 sequences, promoters containing these mutations were activated when cotransfected with the USF1 expression vector (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, these point mutations had greater fold-inductions with cotransfected with USF1 than did the wild-type promoter (Fig. 5B), suggesting either that endogenous levels of USF1 interfered with transactivation or that the mutations diminished binding of other factors that interfered with USF1 binding to the element. In sum, the data show that USF1 interacts with the E box in vivo and transactivates the SF-1 promoter.

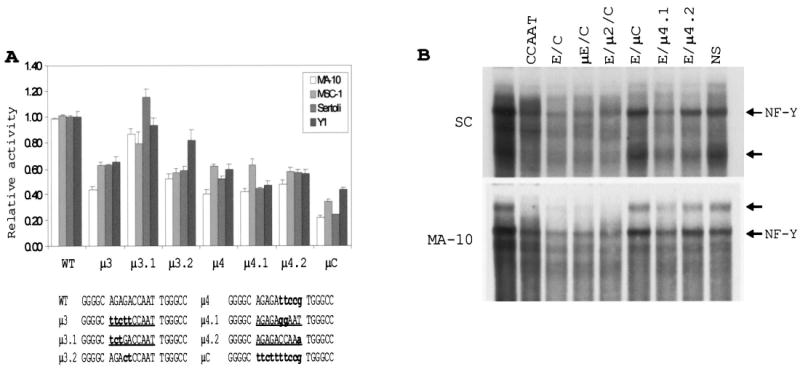

Mutations of the CCAAT Box That Affect Promoter Activity Also Disrupt Binding of Protein Complexes

Similar to the analysis of the E box, smaller mutations within the CCAAT box were generated and evaluated for their impact on promoter activity by transient transfection analysis in Sertoli, Leydig, and adrenocortical cells. Mutations of bases within the core CCAAT sequence (μ 4, μ 4.1, and μ 4.2) as well as sequences directly flanking the element on the 5′ side (μ 3 and μ 3.2) disrupted activity of the promoter (Fig. 6A). However, none of these mutations diminished promoter activity to the same extent as a block replacement through both the flanking and core bases (Fig. 6A, μ C). Previous studies revealed that mutation of the sequences 3′ to the element as well as complete replacement of intervening region 2 (Fig. 1) did not impact basal promoter activity in testicular cells [37]. Collectively, the results show that an intact GACCAAT sequence, composed of the core CCAAT box and the 5′ flanking base doublet, is required for full function of this element.

FIG. 6.

Mutations within the core CCAAT box decrease promoter activity and disrupt recognition by nuclear factors. A) Mutations of the CCAAT box and its 5′ flanking region were prepared and placed in the context of the SF1(− 734/+60)Luc. The promoter activities were determined by transient transfection and normalized to the activity of the wild-type construct as described in Figure 4. The sequences of the different mutants from positions − 76 to − 56 are given at the bottom. The CCAAT boxes and their 5′ flanking regions are underlined. Lowercase, bold letters indicate the base substitutions. B) EMSAs were performed with 50 fmol of CCAAT box probe together with nuclear proteins prepared from Sertoli or MA-10 cells. Competitor oligodeoxynucleotides, as specified above each lane, were added to the binding reactions at 150-fold molar excess. Sequences of the probe and competitors are presented in Table 2. Arrows indicate positions of specific complexes.

The EMSA of the proteins binding the CCAAT box (Table 2) revealed several specific complexes that required an intact element, one of which previously cross-reacted with the NF-Y antibody (Figs. 3 and 6B, arrows). The requirement for an intact CCAAT box was demonstrated by the failure of an oligodeoxynucleotide carrying a mutant CCAAT box to compete for these complexes (Fig. 6B, compare E/μ C with E/C, μ E/C, and E/μ 2/C). In addition, oligodeoxynucleotides carrying the μ 4.1 and μ 4.2 mutations were used as competitors in an EMSA, and the results showed that each mutation disrupted binding of the observed complexes, but not to the same degree as the more extensive μ C mutation (Fig. 6B, compare μ C and E/μ 4.1 and E/μ 4.2). Of the two smaller mutations, μ 4.2 was the least effective competitor and, therefore, had the greatest impact on binding (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, these two mutations had similar detrimental effects on promoter activity, suggesting that these two distinct mutations alter both the binding properties and the functionality of the CCAAT box. Lastly, an oligodeoxynucleotide containing the CCAAT box alone competed less efficiently for the binding complexes than did oligodeoxynucleotides containing the CCAAT box, E box, and intervening sequence (Fig. 6B, compare CCAAT and E/C), revealing that inclusion of the 5 ′ flanking bases stabilized the complexes.

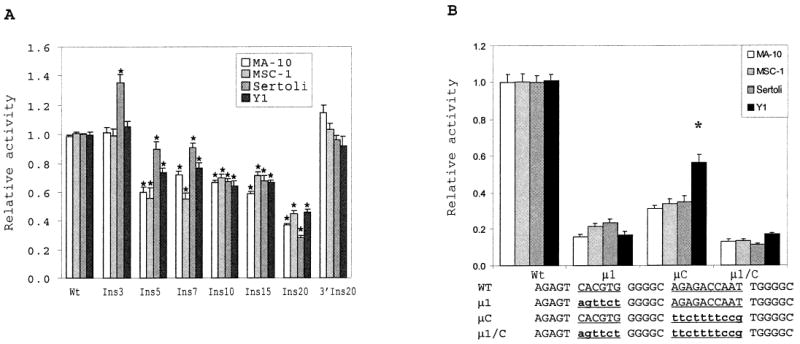

Synergistic Interactions Between the E Box and CCAAT Box Are Important for SF-1-Promoter Activity

To test whether interactions between the proteins binding the E box and CCAAT box are important, insertions of various lengths, ranging from 3 bp (Ins3) to 20 bp (Ins20), were introduced between the second and third guanine residue of the element’s intervening sequence (GGG(AG)nGGC). Evaluation of the mutant promoters in various cell types demonstrated that changing the number of bases between the two elements decreased promoter activity (Fig. 7A). Except in primary Sertoli cells, which showed elevated promoter activity, no change was observed with an insertion of 3 bp (Ins3). However, in all cell types, a significant decrease in promoter activity was found when an insertion of five nucleotides was introduced (Fig. 7A). An increase from 5 to 15 nucleotides had little additional effect, whereas increasing the insertion distance to 20 bp diminished promoter activity by 60–70%. Importantly, insertion of the same 20 nucleotides downstream of the CCAAT box had little or no impact on promoter activity, establishing that the change in activity resulted from altering the distance between the two elements, not the distance between the E box and the downstream promoter region (Fig. 7A, 3′Ins20).

FIG. 7.

Interactions between the E box and CCAAT box are important for SF-1 promoter activity. A) The E box and CCAAT box in the wild-type SF1(− 734/+ 60)Luc reporter construct were incrementally spaced by inserting repetitions of the (AGA)n trinucleotide (mutants Ins3 through Ins20). In mutant 3′ Ins20, the 20-nucleotide insert was introduced downstream to the CCAAT box (into region 5; see Fig. 1). The promoter activities were determined by transient transfection and normalized to the activity of the wild-type construct as described in Figure 4. The sequences of the insertion mutants are described in Materials and Methods. For each cell type, values of the mutants that are statistically different from the wild type are indicated by an asterisk. B) A double block replacement of the E box and CCAAT box (μ 1/C) was generated in the context of SF1(− 734/+60)Luc and the activity of the resulting promoter determined in four cell types as described in Figure 4. The sequences of the mutants from positions − 87 to − 57 are given at the bottom. The functional boxes are underlined, and the base changes are in lowercase, bold letters. Asterisks indicate significantly higher activity of mutant μ C in Y1 than in the three other cell types.

To further substantiate this finding, activity of promoters carrying either a mutation in the E box, CCAAT box, or both elements was evaluated and compared in each cell type. Addition of the CCAAT box to the double-mutant background (Fig. 7B, compare μ 1 to μ 1/C, and Table 3) increased promoter activity 1.0- to 2.0-fold depending on the cell type, whereas addition of the E box (Fig. 7B, compare μ C to μ 1/C, and Table 3) increased promoter activity 2.38-fold (MA-10) to 3.29-fold (Y1). However, addition of both elements resulted in greater activation (6- to 8-fold) than the sum of the individual elements (3- to 5-fold), indicating a synergism between the two (Fig. 7, compare μ 1/C and Wt, and Table 3). Mutagenesis of the CCAAT box (μ C) in Y1 cells decreased promoter activity by 50%, whereas a 65–70% reduction was measured in the three other cell types (Fig. 7B).

TABLE 3.

Promoter activation of μ 1/μ C mutant promoter.a

| Cells | + CCAAT box | + E box | + CCAAT box and E box (wt) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MA-10 | 1.23 | 2.38 | 7.7 |

| MSC-1 | 1.57 | 2.42 | 7.1 |

| P. Sertoli | 2.0 | 2.92 | 8.3 |

| Y-1 | 1.0 | 3.29 | 6.0 |

The table gives the activation folds of the μ 1-μ C promoter observed after addition of the wild-type CCAAT box, E box, or both boxes. The relative activities were taken from Figure 7B.

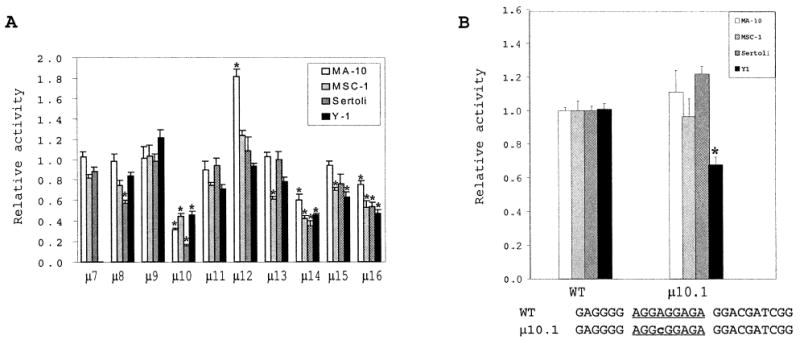

Three SP1/3-Binding Sites Contribute to Basal Promoter Activity

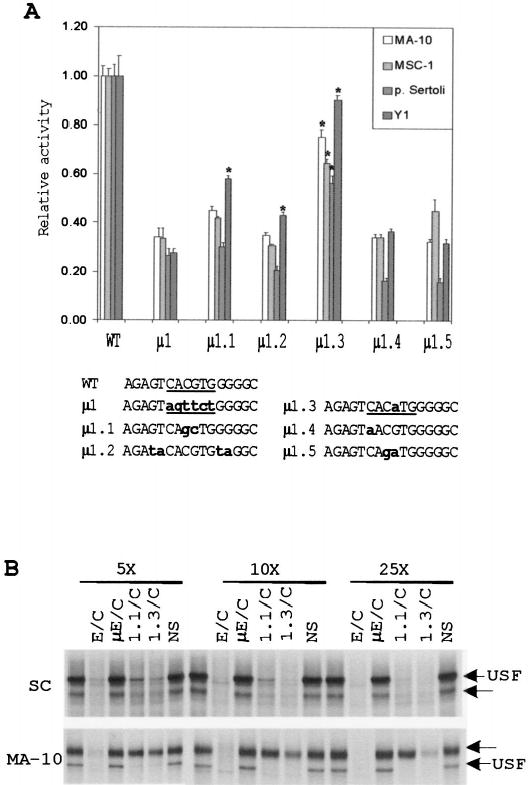

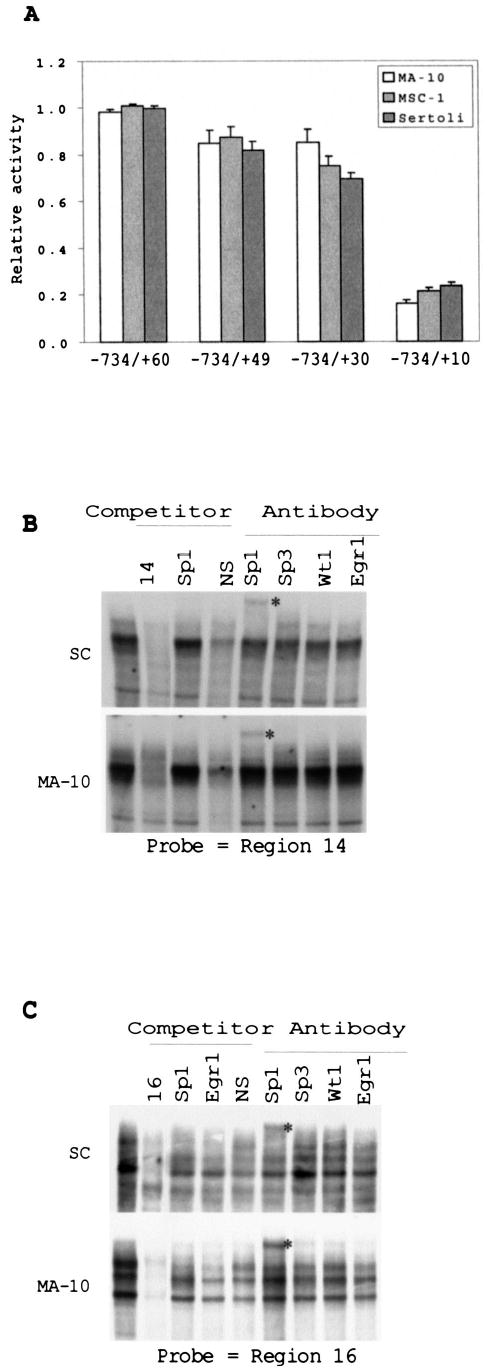

To complete the identification of basal regulatory elements within the proximal promoter region of SF-1, we generated a series of block-replacement mutants spanning positions − 50 to +30 (Fig. 1B, μ 7 through μ 16). Each of the mutant promoters was transiently transfected into Sertoli, MA-10, MSC-1, or Y1 cells, and the transcriptional activity was assessed. Several of the mutations had only modest or no effect on promoter activity in the majority of cells tested. These included μ 7, μ 9, μ 12, μ 13, and μ 15 (Fig. 8A). Interestingly, activity of the μ 12 mutation was elevated only in MA-10 cells, with an 80% increase in promoter activity. Other examples of differential effects on the promoter were observed with the μ 8 mutation, which slightly decreased promoter activity in primary Sertoli cells, and the μ 13 mutation, which had a greater impact in MSC-1 cells (~40% reduction). Mutation μ 16 significantly influenced promoter function in all four cell types, yet the most significant changes in promoter activity were observed with the μ 10 and μ 14 mutations. Conversion of region 10 to a consensus Sp1-binding site (KRGGCKRRK) decreased promoter activity only in Y1 cells (μ 10.1, 5′ -AGGAG-GAGA-3′ to 5′ -AGGCGGAGA-3′ ) (Fig. 8B), where an approximately 30% decrease in promoter activity was observed. Importantly, these studies identified two new elements, represented by μ 14 and μ 16, located downstream of the transcription start site. Serial deletions of the 3′ region delimited by positions +10 and +30 confirmed the presence of elements contributing to promoter function after position +10 (see below and Fig. 10A).

FIG. 8.

Three Sp elements participate in basal SF-1 promoter activity. A) Sequential block replacements were generated in the region from positions − 50 to +30 of the SF-1 promoter (regions 7–16) and placed upstream of the luciferase reporter gene in the context of either SF1(− 734/+30)Luc or SF1(− 734/+60)Luc (see Materials and Methods). The promoter activity of each mutant was subsequently assessed by transient transfection of MA-10, MSC-1, primary Sertoli cells, and Y1 cells as described in Figure 4. Sequences of μ 7 through μ 16 are given in Figure 1B. Asterisks denote the values that are significantly different from the wild-type control for each cell type (P < 0.01). B) A conservative base change within the potential Sp1-binding site of region 10 does not perturb promoter activity. A single nucleotide replacement in region 10 (μ 10.1) was produced and promoter activity determined as described in A. Sequence of the mutant (positions − 33 to − 9) is given under the graph. Region 10 is underlined, and the lowercase, bold ‘‘c’’ indicates the A → C base substitution that preserves the Sp1-binding motif. Error bars represent the SEM. Asterisks indicate statistically lower activity of μ 10.1 in transfected Y1 cells than in the wild-type control.

FIG. 10.

Two downstream GC-rich elements that bind Sp1 in vitro play a role in promoter activity. A) The sequence between positions +30 and +10 is important for promoter activity. Three promoter fragments with increasing deletions 3′ to the transcription start site were introduced into the SF-1 promoter. Promoter activities were analyzed by transient transfection of MA-10, MSC-1, and Sertoli cells, and the activities are expressed relative to the original SF1(−734/+60)Luc construct (see Fig. 4). Error bars represent the SEM. B) EMSAs were conducted using a probe to region 14 and nuclear proteins of either Sertoli or MA-10 cells. Where indicated above the lanes, binding reactions were performed in the presence of a 200-fold excess of competitor oligodeoxynucleotides or antibodies against Sp1, Sp3, Wt1, and Egr1. C) EMSAs were performed as described in A but with a probe to region 16, and competitors for reactions performed with Sertoli cell (SC) extracts were added at 100-fold molar excess. Sequences of the probes and competitors are given in Table 2. The supershifted complexes are denoted by asterisks to the right of the lanes, and the SP1-containing bands are indicated by arrows.

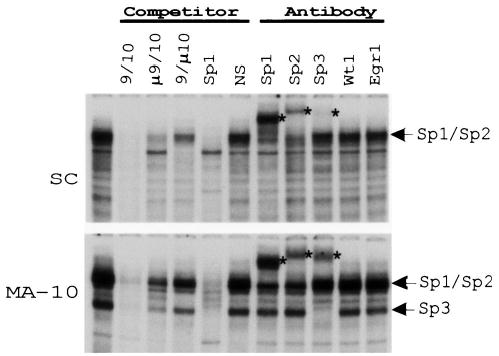

To identify proteins binding the important element contained in region 10, EMSAs were performed that employed MA-10 and Sertoli cell nuclear extracts. In both cell types, a single prominent specific complex was observed in addition to several smaller ones (Fig. 9). In particular, a second complex is seen under the major complex in MA-10 cells. Competition with an oligodeoxynucleotide containing a mutation in the region 9 (μ 9/10), which did not impact promoter activity, partially competed the complexes, whereas an oligodeoxynucleotide containing a mutation in region 10 (9/μ 10), which had a significant impact on promoter activity, was less effective. This indicates that the observed binding complexes required bases within both regions 9 and 10, but that mutations within region 9 allowed sufficient binding of the proteins to activate the promoter. In both cell types, a consensus oligodeoxynucleotide for Sp1 was able to compete with most of the complexes (Fig. 9). Antibodies generated against Sp1, Sp2, and Sp3, when used in the EMSA, cross-reacted with complexes in each cell type. The upper complex in Sertoli and Leydig cells interacted mostly with Sp1 and Sp2 antibodies, whereas a lower band in MA-10 cross-reacted with the Sp3 antibody. Some cross-reactivity was observed with the Sp3 antibody in Sertoli cells, but the Sp3-containing complex was significantly more prominent in MA-10 cells (Fig. 9).

FIG. 9.

Proteins of the Sp family bind to region 10 of the rat SF-1 promoter. EMSAs were performed with a radiolabeled probe spanning regions 9 and 10 (9/10) and nuclear extracts from either Sertoli or MA-10 cells. Where indicated above the lanes, experiments were carried out in the presence of 150-fold molar excess of competitor oligodeoxynucleotides or antibodies to the transcription factors Sp1, Sp2, Sp3, Wt1, and Egr1. Sequences of probe and competitors are given in Table 2. Arrows indicate the positions of the major specific complexes, whereas asterisks indicate the supershifted complexes.

Regions 14 and 16 are both rich in guanines and cytosines, and EMSA studies revealed several binding complexes to each site (Fig. 10). Proteins from MA-10 and Sertoli cell extracts bound these elements, some of which were supershifted with the Sp1 antibody (Fig. 10, B and C). Surprisingly, nonspecific competitor efficiently removed some complexes bound to these regions, suggesting that a significant amount of nonspecific protein is bound to the elements. The other bound complexes have not been identified, but antibodies against Sp3, Wt1, and Egr1 failed to cross-react with them.

DISCUSSION

Since the discovery of SF-1, many studies have examined its expression profile and demonstrated its highly tissue-specific distribution [13]. However, the mechanisms that regulate SF-1 and that contribute to its tissue-specific expression are poorly understood. Previously published reports have defined some of the cis-elements and trans-factors that contribute to SF-1 promoter activity, identifying a role for a Sox9 site, E box, CCAAT box, and Sp1 site [38–41]. However, only a fraction of the functional promoter region was evaluated for potential elements, and studies were limited to a subset of SF-1-expressing cells. To add to our understanding of the mechanisms directing SF-1 transcription, we have extended the analysis of the SF-1 proximal promoter using a block-replacement approach and compared promoter activities between adrenal and two testis-derived cell types. The present study more completely defines the cis-elements located within the SF-1 proximal promoter, identifies proteins and complexes binding these regulatory sites (E box, CCAAT box, and Sp1-binding sites) in the testis, and reveals an important cooperation between the transcription factors binding the E box and CCAAT box elements.

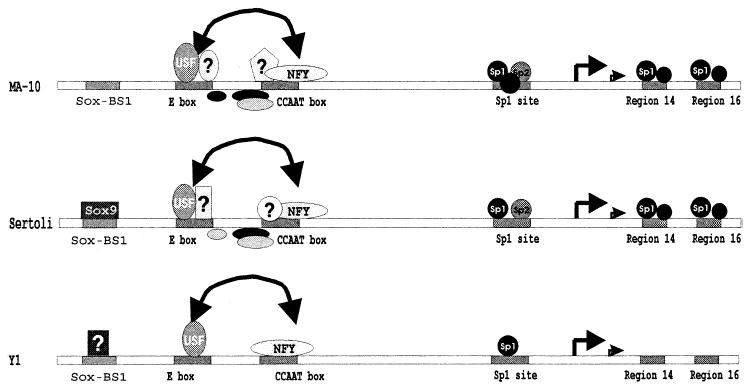

Earlier observations indicated that the region between −87 and +60 possessed the majority of activity associated with the SF-1 promoter. Within this region, five cis-regulatory elements contribute to promoter activity in testicular cells (Fig. 11). The E box and CCAAT box play a predominant role in the regulation of SF-1 transcription, and the close proximity of the E box and CCAAT box led to the hypothesis that the two elements function together. Data presented in the present study indicate that proteins binding these elements cooperate with each other and synergistically activate the SF-1 promoter. This functional synergism seems to require both an optimal distance between the E box and CCAAT box and a given orientation of those elements. A spacing of 5–8 bp was optimal (Fig. 7A). The deleterious effect of further separation, resulting in a half-turn or more of the DNA helix, suggests that physical interactions between the bound factors are critical. Currently, however, which transcriptional regulators are critical for activity at the E box and CCAAT box is not clear, because multiple specific complexes interact with the elements and only some of these have been identified by antibody supershift studies (USF1, USF2, and NF-Y). Interestingly, these studies identified cell-specific differences in the proteins binding these elements, because EMSA showed that complexes from Leydig and Sertoli cells had different mobilities.

FIG. 11.

Model for transcriptional regulation of the SF-1 gene. Shown is a schematic representation of the protein complexes that bind the SF-1 proximal promoter between positions −120 and +30 together with their recognition sites in MA-10 (top), Sertoli cells (middle), and Y-1 cells (bottom). Efficient transcription requires input from six cis-acting elements: the Sox-BS1 site, E box, CCAAT box, the Sp1 site, and elements within regions 14 and 16. Interaction between the E box and CCAAT box is indicated by the double-headed arrow. The bent arrows mark the identified transcription start sites (major site at +1). The known factors (Sox9, USF, NF-Y, and Sp proteins) that interact with the proximal promoter in vitro are specified as well as those that have not yet been identified. These include specific complexes that bind the intervening region between the E box and the CCAAT boxes as well as those that bind within these elements. Regulation of SF-1 through binding of Sox9 to the Sox-BS1 site in MA-10 cells remains unclear [41].

Because multiple protein complexes bound the E box and CCAAT box, each must be considered a potential transcriptional regulator of SF-1. The USF proteins were identified as candidates for E box regulatory proteins, and the present study provides functional evidence that USF1 can activate the SF-1 promoter through the E box (Figs. 3A and 5A). In support of this, the E box mutational analysis showed that the preferred bases of the E box (CACGTG) conformed to those identified for a class of bHLH-ZIP factors that include USF1, USF2, Myc, Mad, Max, and TFE3. These data also suggested that complexes containing ubiquitous class A bHLH factors (i.e., E12, E47, ITF1, ITF2, and HEB) were not responsible for activation of the SF-1 promoter [46]. As with the E box, two major complexes bound the CCAAT box, one of which was identified as the transcription factor NF-Y (Figs. 3B and 11). Woodson et al. [38] previously observed binding of this factor to the SF-1 CCAAT box in Y1 cells, and accordingly, the present study extends this finding to cells of the testis. This transcription factor is composed of three subunits that are often found associated with TATA-less promoters [47, 48]. Among the many proteins that bind a CCAAT box motif (i.e., C/EBP, CTF, and CDP), NF-Y (also called CBF) is the only factor requiring conservation of the entire CCAAT pentanucleotide for binding [49]. Thus, the necessity for the CCAAT sequence and the 5′ flanking dinucleotide is consistent with the requirements for NF-Y binding. In sum, the current evidence suggests that USF1, USF2, and NF-Y regulate SF-1 in multiple, different cell types. However, the discovery of unidentified proteins that bind these elements suggests the intriguing possibility that these new complexes play critical regulatory roles specific to Sertoli or Leydig cells. It is therefore tempting to speculate that the proteins specific to the Leydig cells are somehow linked to the steroidogenic role of SF-1 whereas the proteins specific to the Sertoli cells are associated with its developmental role. Alternatively, these new complexes may help to direct the cell-specific expression of SF-1, because the ubiquitous nature of USF and NF-Y make them unlikely candidates for such a function. Additional studies are required to determine the identity of these other complexes and to reveal their role in SF-1 transcription.

Complete analysis of the proximal promoter extending from −87 to +60 revealed only three additional mutations that disrupted promoter activity in the testis-derived and adrenocortical cells. One of these regions, region 10, was previously identified in Y1 cells as an Sp1-binding site; thus, the present study expands the functional relevance of this Sp1 site to Leydig and Sertoli cells [38]. Importantly, two novel elements were revealed downstream of the transcriptional start site (Fig. 11). In the testis, these three elements bound transcription factors that are members of a family of Sp1-like proteins, which are zinc-finger transcription factors expressed in a variety of cells and tissues [50]. Similar to what was observed in Y1 cells, the upstream binding site (region 10) bound predominantly Sp1 in the testis [38]. However, a significant amount of Sp3 binding was observed in MA-10 extracts, suggesting that regulation of SF-1 by this transcription factor may be favored in Leydig cells. Interestingly, the present study also identified a functional variation in this upstream element between different cell types. Thus, a single base pair change in the core of the element was deleterious only in Y1 cells (Fig. 9B). Such a difference indicates that, whereas similar elements are employed in the different tissues, mechanistic differences exist in the proteins used or their functional properties. Studies on mice lacking Sp1 suggested that this transcription factor plays a critical role in the maintenance of differentiated cells [51]. Ubiquitous expression patterns for Sp1 and Sp3 indicate they are not directly responsible for restricting SF-1 expression, but the functional implications from the Sp1 gene-knockout studies suggest they are important for sustained expression of the gene [51].

In summary, a combinatorial repertoire of factors is needed for transcriptional activity of the SF-1 promoter (Fig. 11). Comparison of promoter activity in three different cell types revealed that a similar set of cis-acting elements directs expression of SF-1 in these cells. However, notable differences between cell types were apparent in the trans-factors interacting with these elements. In Sertoli and Leydig cells, USF1, USF2, and other cell-specific proteins are implicated in regulation of the E box. In contrast, only the USF proteins were observed to bind the E box in Y1 cells [40]. Similarly, the CCAAT box binds NF-Y (CBF) in each cell type, but in addition, different binding complexes were observed in Leydig and Sertoli cells. No such second CCAAT-binding complex was observed in Y1 cells [38]. Finally, in the three cell types analyzed, synergism was observed between the E box and CCAAT box activities, which to our knowledge is the first report for such an interaction on the SF-1 promoter (Fig. 11). Consequently, our results, taken as a whole, suggest that several ubiquitous factors (USF proteins, NF-Y, and Sp factors) and other unknown proteins are needed for expression of SF-1 in the testis, and that direct protein-protein interactions, facilitative binding, or cooperative use of a coactivator are critical for expression of SF-1. Additional studies to identify the unknown proteins and to determine the nature of the synergistic interaction are needed to fully understand regulation of SF-1.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. K.S. McCarter from the Preventive Medicine Department for his assistance with the statistical analysis of the data. In addition, we thank Jiang-kai Chen for cell culture preparation and technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grant R01HD38498 to L.L.H.

References

- 1.Kreidberg JA, Sariola H, Loring JM, Maeda M, Pelletier J, Housman D, Jaenisch R. WT-1 is required for early kidney development. Cell. 1993;74:679–691. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90515-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kent J, Wheatley SC, Andrews JE, Sinclair AH, Koopman P. A male-specific role for SOX9 in vertebrate sex determination. Development. 1996;122:2813–2822. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morais-da-Silva S, Hacker A, Harley V, Goodfellow P, Swain A, Lovell-Badge R. Sox9 expression during gonadal development implies a conserved role for the gene in testis differentiation in mammals and birds. Nat Genet. 1996;14:62–68. doi: 10.1038/ng0996-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swain A, Narvaez V, Burgoyne P, Camerino G, Lovell-Badge R. Dax1 antagonizes Sry action in mammalian sex determination. Nature. 1998;391:761–767. doi: 10.1038/35799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shawlot W, Behringer RR. Requirement for Lim1 in head-organizer function. Nature. 1995;374:425–430. doi: 10.1038/374425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyamoto N, Yoshida M, Kuratani S, Matsuo I, Aizawa S. Defects of urogenital development in mice lacking Emx2. Development. 1997;124:1653–1664. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.9.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birk OS, Casiano DE, Wassif CA, Cogliati T, Zhao L, Zhao Y, Grinberg A, Huang S, Kreidberg JA, Parker KL, Porter FD, Westphal H. The LIM homeobox gene Lhx9 is essential for mouse gonad formation. Nature. 2000;403:909–913. doi: 10.1038/35002622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gubbay J, Collignon J, Koopman P, Capel B, Economou A, Munsterberg A, Vivian N, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R. A gene mapping to the sex-determining region of the mouse Y chromosome is a member of a novel family of embryonically expressed genes. Nature. 1990;346:245–250. doi: 10.1038/346245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lovell-Badge R, Robertson E. XY female mice resulting from a heritable mutation in the primary testis-determining gene, Tdy. Development. 1990;109:635–646. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.3.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo X, Ikeda Y, Parker KL. A cell-specific nuclear receptor is essential for adrenal and gonadal development and sexual differentiation. Cell. 1994;77:481–490. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vidal VP, Chaboissier MC, de Rooij DG, Schedl A. Sox9 induces testis development in XX transgenic mice. Nat Genet. 2001;28:216–217. doi: 10.1038/90046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ninomiya Y, Okada M, Kotomura N, Suzuki K, Tsukiyama T, Niwa O. Genomic organization and isoforms of the mouse ELP gene. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1995;118:380–389. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parker KL, Schimmer BP. Steroidogenic factor 1: a key determinant of endocrine development and function. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:361–377. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadovsky Y, Crawford PA, Woodson KG, Polish JA, Clements MA, Tourtellotte LM, Simburger K, Milbrandt J. Mice deficient in the orphan receptor steroidogenic factor 1 lack adrenal glands and gonads but express P450 side-chain-cleavage enzyme in the placenta and have normal embryonic serum levels of corticosteroids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10939–10943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Achermann JC, Ito M, Hindmarsh PC, Jameson JL. A mutation in the gene encoding steroidogenic factor-1 causes XY sex reversal and adrenal failure in humans. Nat Genet. 1999;22:125–126. doi: 10.1038/9629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo X, Ikeda Y, Schlosser DA, Parker KL. Steroidogenic factor 1 is the essential transcript of the mouse FTZ-F1 gene. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:1233–1239. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.9.7491115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikeda Y, Shen W-H, Ingraham HA, Parker KL. Developmental expression of mouse steroidogenic factor-1, an essential regulator of the steroid hydroxylases. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:654–662. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.5.8058073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen W-H, Moore CD, Ikeda Y, Parker KL, Ingraham HA. Nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor 1 regulates the mullerian inhibiting substance gene: a link to the sex determination cascade. Cell. 1994;77:651–661. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugawara T, Kiriakidou M, McAllister JM, Holt JA, Arakane F, Strauss JF. Regulation of expression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) gene: a central role for steroidogenic factor 1 [published erratum appears in Steroids 1997; 62:395] Steroids. 1997;62:5–9. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(96)00152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugawara T, Kiriakidou M, McAllister JM, Kallen CB, Strauss JF. Multiple steroidogenic factor 1-binding elements in the human steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene 5′-flanking region are required for maximal promoter activity and cyclic AMP responsiveness. Biochemistry. 1997;36:7249–7255. doi: 10.1021/bi9628984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolfe MW. The equine luteinizing hormone beta-subunit promoter contains two functional steroidogenic factor-1 response elements. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:1497–1510. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.9.0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keri RA, Nilson JH. A steroidogenic factor-1-binding site is required for activity of the luteinizing hormone B subunit promoter in gonadotropes of transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10782–10785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorn C, Ou Q, Svaren J, Crawford PA, Sadovsky Y. Activation of luteinizing hormone beta gene by gonadotropin-releasing hormone requires the synergy of early growth response-1 and steroidogenic factor-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13870–13876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tremblay JJ, Drouin J. Egr-1 is a downstream effector of GnRH and synergizes by direct interaction with Ptx1 and SF-1 to enhance luteinizing hormone beta gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2567–2576. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halvorson LM, Ito M, Jameson JL, Chin WW. Steroidogenic factor-1 and early growth response protein 1 act through two composite DNA binding sites to regulate luteinizing hormone beta-subunit gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14712–14720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito M, Park Y, Weck J, Mayo KE, Jameson JL. Synergistic activation of the inhibin alpha-promoter by steroidogenic factor-1 and cyclic adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:66–81. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.1.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnhart KM, Mellon PL. The orphan nuclear receptor, steroidogenic factor-1, regulates the glycoprotein hormone α-subunit gene in pituitary gonadotropes. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:878–885. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.7.7527122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heckert LL. Activation of the rat follicle-stimulating hormone receptor promoter by steroidogenic factor 1 is blocked by protein kinase and requires upstream stimulatory factor binding to a proximal E box element. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:704–715. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.5.0632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levallet J, Koskimies P, Rahman N, Huhtaniemi I. The promoter of murine follicle-stimulating hormone receptor: functional characterization and regulation by transcription factor steroidogenic factor 1. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:80–92. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.1.0583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ngan ES, Cheng PK, Leung PC, Chow BK. Steroidogenic factor-1 interacts with a gonadotrope-specific element within the first exon of the human gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene to mediate gonadotrope-specific expression. Endocrinology. 1999;140:2452–2462. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.6.6759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duval DL, Nelson SE, Clay CM. A binding site for steroidogenic factor-1 is part of a complex enhancer that mediates expression of the murine gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene. Biol Reprod. 1997;56:160–168. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod56.1.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shinoda K, Lei H, Yoshii H, Nomura M, Nagano M, Shiba H, Sasaki H, Osawa Y, Ninomiya Y, Niwa O. Developmental defects of the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus and pituitary gonadotroph in the Ftz-F1 disrupted mice. Dev Dyn. 1995;204:22–29. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002040104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morohashi KI, Omura T. Ad4BP/SF-1, a transcription factor essential for the transcription of steroidogenic cytochrome P450 genes and for the establishment of the reproductive function. FASEB J. 1996;10:1569–1577. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.14.9002548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadovsky Y, Crawford PA. Developmental and physiologic roles of the nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor-1 in the reproductive system. J Soc Gynecol Invest. 1998;5:6–12. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(97)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hatano O, Takayama K, Imai T, Waterman MR, Takakusu A, Omura T, Morohashi K. Sex-dependent expression of a transcription factor, Ad4BP, regulating steroidogenic P-450 genes in the gonads during prenatal and postnatal rat development. Development. 1994;120:2787–2797. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao L, Bakke M, Krimkevich Y, Cushman LJ, Parlow AF, Camper SA, Parker KL. Steroidogenic factor 1 (SF1) is essential for pituitary gonadotrope function. Development. 2001;128:147–154. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daggett MA, Rice DA, Heckert LL. Expression of steroidogenic factor 1 in the testis requires an E box and CCAAT box in its promoter proximal region. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:670–679. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.3.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woodson KG, Crawford PA, Sadovsky Y, Milbrandt J. Characterization of the promoter of SF-1, an orphan nuclear receptor required for adrenal and gonadal development. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:117–126. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.2.9881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nomura M, Bartsch S, Nawata H, Omura T, Morohashi K. An E box element is required for the expression of the ad4bp gene, a mammalian homologue of ftz-f1 gene, which is essential for adrenal and gonadal development. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7453–7461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris AN, Mellon PL. The basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper transcription factor, USF (upstream stimulatory factor), is a key regulator of SF-1 (steroidogenic factor-1) gene expression in pituitary gonadotrope and steroidogenic cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:714–726. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.5.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen JH, Ingraham HA. Regulation of the orphan nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor 1 by sox proteins. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:529–540. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.3.0782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heckert LL, Sawadogo M, Daggett MA, Chen J. The USF proteins regulate transcription of the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor but are insufficient for cell-specific expression. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1836–1848. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.11.0557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luo X, Sawadogo M. Functional domains of the transcription factor USF2: atypical nuclear localization signals and context-dependent transcriptional activation domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1367–1375. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heckert LL, Daggett MA, Chen J. Multiple promoter elements contribute to activity of the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) gene in testicular Sertoli cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1499–1512. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.10.0183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heckert LL, Schultz K, Nilson JH. Different composite regulatory elements direct expression of the human α subunit gene to pituitary and placenta. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26497–26504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Littlewood TD, Evan GI. Transcription factors 2: helix-loop-helix. Protein Profile. 1994;1:639–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maity SN, de Crombrugghe B. Role of the CCAAT-binding protein CBF/NF-Y in transcription. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:174–178. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mantovani R. The molecular biology of the CCAAT-binding factor NF-Y. Gene. 1999;239:15–27. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mantovani R. A survey of 178 NF-Y binding CCAAT boxes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1135–1143. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.5.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cook T, Gebelein B, Urrutia R. Sp1 and its likes: biochemical and functional predictions for a growing family of zinc finger transcription factors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;880:94–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marin M, Karis A, Visser P, Grosveld F, Philipsen S. Transcription factor Sp1 is essential for early embryonic development but dispensable for cell growth and differentiation. Cell. 1997;89:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]