Abstract

Fusobacterium nucleatum is a Gram-negative anaerobe important in dental biofilm ecology and infectious diseases with significant societal impact. The lack of efficient genetic systems has hampered molecular analyses in this microorganism. We previously reported construction of a shuttle plasmid, pHS17, using the native fusobacterial plasmid pFN1 and an erythromycin resistance cassette. However, the host range of pHS17 was restricted to F. nucleatum, ATCC 10953 and the transformation efficiency was limited. This study was undertaken to improve genetic systems for molecular analysis in F. nucleatum. We identified a second F. nucleatum strain, ATCC 23726, which is transformed with improved efficiency compared to ATCC 10953. Two novel second generation pFN1-based shuttle plasmids, pHS23 and pHS30, were developed and enable transformation of ATCC 23726 at 6.2 x 104 and 1.5 x 106 transformants/microgram of plasmid DNA, respectively. The transformation efficiency of pHS30, which harbors a catP gene conferring resistance to chloramphenicol, was more than 1,000-fold greater than that of pHS17. The improved transformation efficiency facilitated disruption of the chromosomal rnr gene using a suicide plasmid pHS19, the first demonstration of targeted mutagenesis in F. nucleatum. These results provide significant advances in the development of systems for molecular analysis in F. nucleatum.

Keywords: Fusobacterium nucleatum, shuttle plasmid, transformation, mutagenesis

INTRODUCTION

Fusobacterium nucleatum is a Gram-negative anaerobic microorganism that is important in the ecology of dental plaque biofilms and in human infectious diseases with significant societal impact. It is one of the early Gram-negative anaerobes to colonize the oral cavity (27), where it is a numerically dominant species in dental plaque biofilms that form on tooth surfaces (31, 36, 40). Initial plaque biofilms consist predominately of Gram-positive facultative species that provide a substrate for the subsequent colonization of the predominately Gram-negative anaerobic population that characterizes mature biofilms. F. nucleatum adheres to a wide range of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative species, suggesting a key role in the structural formation and physiological interactions of biofilm development (26). Studies of planktonic and biofilm oral microbial communities indicate that F. nucleatum enhances the survival of strict anaerobic species, such as Prevotella nigrescens and Porphyromonas gingivalis (4, 11). The ability of F. nucleatum to contribute to the maintenance of reduced conditions may be important to its ability to protect less oxygen tolerant anaerobes (11), allowing for their emergence in the biofilm environment. F. nucleatum is consistently associated with periodontitis, one of the most common infectious diseases in humans. In addition, it is the most common of the periodontal species found in extraoral infections, including blood, brain, chest, lung, liver, joint, abdominal and obstetrical and gynecological infections and abscesses (5, 6, 9, 10, 16, 20, 21, 31). F. nucleatum infections of the vagina and amnionic fluid are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes (19, 20, 39) and recent studies demonstrated that F. nucleatum induces premature delivery, stillbirths and non-sustained live births in a rodent model system (17).

Despite the importance of F. nucleatum in microbial ecology and pathogenesis, relatively little is known about the bacterial determinants of significance in interactions with other bacteria or host tissue cells. Of potential importance are F. nucleatum adherence properties, mechanisms relating to invasion and modulation of host tissue cells including the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and the production of elastase and tissue toxic metabolic by-products such as butyric acid. The emergence of penicillin-resistant strains of F. nucleatum over the last two decades is of particular concern in the management of fusobacterial infections (16, 28, 33, 38).

F. nucleatum encompasses a heterogenous group of microorganisms, with five recognized subspecies (13, 15). Genomic DNA sequence is currently available for strains representing three dominant oral subspecies, nucleatum, vincentii, and polymorphum. A primary limitation in studies of F. nucleatum has been the lack of efficient genetic systems for molecular manipulation. We previously used the native F. nucleatum plasmid, pFN1 to construct an intergeneric E. coli – F. nucleatum shuttle plasmid, pHS17 (24). However, the transformation of F. nucleatum with pHS17 was limited in efficiency (2 X 101 transformants per microgram of DNA) and only a single strain of F. nucleatum (ATCC 10953) was reported to be transformed.

This investigation was undertaken to address host strain and vector deficiencies in genetic transfer systems with the goal of developing a system to enable the generation of chromosomal mutations in F. nucleatum. Our findings document an additional strain of F. nucleatum, ATCC 23726, that is transformable; describe second generation pFN1-based shuttle plasmids with 50- to greater than 1,000-fold improvement in transformation efficiency; describe an additional antimicrobial resistance determinant, catP, for use as a selectable marker in F. nucleatum; and provide the first demonstration of integration mutagenesis of a chromosomal F. nucleatum gene.Together these findings document a genetic system for F. nucleatum that will enable molecular analysis of the role of specific gene products in properties important in ecology and pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

The Fusobacterium strains (Table 1) were cultured anaerobically on Columbia agar with 5% sheeps’ blood or in Columbia Broth. Escherichia coli DH5α (Invitrogen Co., Carlsbad, CA) was cultured aerobically on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar or in LB broth, as previously described (24). The concentrations of antibiotic added to agar media for cultivation of F. nucleatum transformants were 5 micrograms ml−1 of a chloramphenicol analog thiamphenicol (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO; resuspended as a stock solution at 5 mg/ml in ethanol) and unless otherwise noted 0.4 micrograms ml−1 of clindamycin (Sigma Chemical Co.); for E. coli 50 micrograms ml−1 of chloramphenicol (Fisher Scientific, Tustin, CA) and 300 micrograms ml−1 of erythromycin (Fisher Scientific, Tustin, CA). The antibiotic concentration used in broth cultures was 50% of that used in the agar medium.

Table 1.

Fusobacterium strains and Plasmids Used

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Description1 | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains2 | ||

| F. nucleatum ATCC 10953 | Wild type strain, ssp. polymorphum; harbors native plasmid pFN3 | ATCC3 |

| F. nucleatum ATCC 23726 | Wild type strain, ssp. nucleatum | ATCC |

| E. coli DH5α | Host strain for propagation of genetic constructs; F-Φ80lacZΔM15endA1 recA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 Δ(lacXYA-argF) U169 | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pFN1 | 8.0 kb cryptic plasmid, native to F. nucleatum WAL12230 | (24) |

| pBluescript | 3.0 kb plasmid used as backbone in shuttle plasmid constructs; ampr | Strategene, Inc. |

| pHS19 | 4.1 kb plasmid constructed by cloning erm resistance cassette (ermF-ermB) into pBluescript followed by deletion of ampicillin resistance gene; ermr clinr | (24) |

| pHS17 | 10.0 kb shuttle plasmid constructed from pBluescriptΔbla, pFN1, and the erm cassette; ermr clinr | (24) |

| pHS23 | 8.0 kb shuttle plasmid derived from pHS17 by deletion of a 2.0 kb HpaI fragment that eliminated the pFN1 rlx gene; ermr clinr | This study |

| pHS25 | 8.6 kb plasmid derived from pHS17 by deletion of a 1.4 kb XbaI fragment eliminating the pFN1 ori □ □ □ □’ region of the repA gene, ermr clinr | This study |

| pHS100 | 4.8 kb integration plasmid constructed by insertion of a731 bp PCR-amplified 5’ fragment from the ATCC 23726 chromosomal rnr gene into the XhoI-ClaI restricted pHS19, ermr clinr | This study |

| pJIR750 | 6.6 kb plasmid possessing ColE1 origin, and a C. perfringens replicon and catP gene; camr | (1) |

| pHS30 | 7.3 kb shuttle plasmid constructed from a 3.3 kb fragment of pJIR750 encoding a ColE1 origin and catP gene, with a 4.0 kb fragment of pHS23 encoding the pFN1ori and repA gene; camr | This study |

| Primers4 | ||

| IP1 | 5’-GCTCGAGAAGACTTAGATGATGCTG-3’; forward primer for integration plasmid 731 bp rnr gene fragment with XhoI site | |

| IP2 | 5’-CAATAAATCGATGAAATTGTTTAGG-3’; reverse primer for integration plasmid 731 bp rnr gene fragment with ClaI site | |

| PA1 | 5’-GCAATGCAACAAACTAAG-3’; forward primer specific to rnr gene 5’ to integration plasmid fragment, used in PCR analyses | |

| PA2 | 5’-ATCTAAAACCGTATCCTG-3’; reverse primer specific to erm cassette located 3’ to integration plasmid fragment, used in PCR analyses | |

| SA1 | 5’-AACATAGACTTTCATTACCAG-3’; forward primer for 1.672 kb rnr gene probe used in Southern analyses | |

| SA2 | 5’-TTTTATTCTTACACTTTCATC-3’; reverse primer for 1.672 kb rnr gene probe used in Southern analyses | |

Amp: ampicillin, erm: erythromycin, clin: clindamycin, cam: chloramphenicol/thiamphenicol.

The clindamycin concentrations used for recovery of transformants was 0.4 micrograms per ml. Strains tested that did not yield transformants included F. nucleatum ATCC 25586, ATCC 49256, ATCC 51190, Wadsworth Anaerobe Lab (WAL) 12230, WAL 11013, T18, GXA6, 191; as well as F. periodonticum ATCC 33693, F. varium ATCC 8501, F. necrophorum ATCC 25286, F. mortiferum ATCC 25557 and F. varium ATCC 27725.

ATCC: American Type Culture Collection

The underlined regions are primer sites inserted for the purpose of subsequent cloning.

Recombinant DNA Techniques and Plasmids

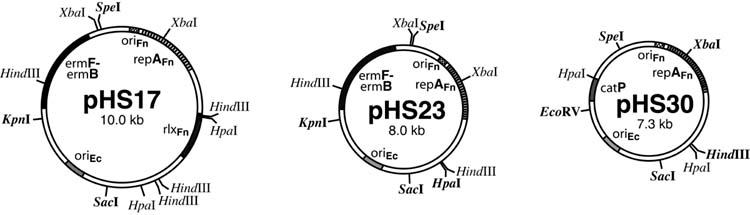

Restriction endonucleases, DNA-modifying enzymes and Taq polymerase were obtained from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA), Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO), or Fisher Scientific (Tustin, CA). The plasmid pHS19 consists of an erythromycin cassette (14) cloned into a pBluescript backbone (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with the ampicillin resistance gene deleted (Δbla), as previously described (24). The intergeneric F. nucleatum – E. coli shuttle plasmid pHS17 (Figure 1) consists of pHS19 with the addition of the native F. nucleatum plasmid pFN1 (24). The deletion derivates of pHS17 were constructed by religation of the plasmid following restriction endonuclease digestion to delete an internal fragment corresponding to specific regions of the pFN1 portion of the plasmid (Table 1, Figure 1). In this manner, pHS23 was constructed by deletion of a 1933 bp HpaI fragment and pHS25 by a deletion of a 1346 bp XbaI fragment. For construction of pHS30, a SpeI-SacI-KpnI digest of pHS23 was used to isolate the 4.0 kb SpeI-SacI fragment that harbors the pFN1 origin of replication (ori) and repA, which was then ligated to a 3.3 kb SpeI-SacI fragment of pJIR750 possessing the E. coli ColE1 ori and the Clostridium perfringens catP gene for chloramphenicol resistance (Figure 1). Plasmid DNA was introduced into E. coli by transformation of MAX Efficiency® DH5α™ Competent Cells (Invitrogen Co., Carlsbad, CA). Plasmids were isolated with an alkaline lysis/column purification technique using commercially available kits (Qiagen Midi and Maxi Preps, Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA; Strataprep EF Midi preps, Stratagene Cloning Systems; Wizard® Plus Midipreps, Promega Co., Madison, WI). Plasmid DNA was further purified for use in electroporation using cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation, as previously described (24). DNA concentrations were determined by spectrophotometry at 260 nm. All DNA preparations were stored in TE (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) at −20°C. Plasmid DNA was dialyzed for desalting as a drop on a 0.025 □m membrane (Millipore “V” series membranes, Millipore Co., Bedford, MA; http://www.millipore.com/publications.nsf/docs/PF723) floating on sterile ddH2O for 30 minutes prior to use in electroporation.

Figure 1. pFN1-based shuttle plasmids.

A. The first generation pHS17, and second generation pHS23 and pHS30 shuttle plasmids are illustrated schematically with relevant replication origins, genes and restriction endonuclease sites indicated. pHS23 was constructed by deletion of the HpaI fragment of pHS17, resulting in elimination of the pFN1 rlx gene. The pFN1 fragment in pHS23 and pHS30, encoding the fusobacterial replicon, are identical. pHS17 and pHS23 possess the erm cassette and confer macrolide resistance, whereas pHS30 possesses the catP gene and confers resistance to chloramphenicol and thiamphenicol. All sites for the designated restriction endonucleases indicated, and unique sites within a given plasmid are indicated in bold type.

Electroporation

Gradient purified plasmid DNA was introduced into F. nucleatum by electroporation, as described below. F. nucleatum cells were grown to log phase, harvested by centrifugation, washed twice and resuspended in electroporation buffer (10% glycerol, 1 mM MgCl2, 4°C) (4) to an effective cell concentration (ECC) of 6.0 (where ECC = OD600 × concentration factor). Plasmid DNA was added to one hundred-μl aliquots of the prepared F. nucleatum cells in pre-cooled cuvettes (0.1 cm gap; BioRad, Hercules, CA), followed by incubation on ice for 10 min. The reactions were subject to electroporation using a BioRad Gene Pulser II set at a field strength of 25 kV/cm and capacitance of 25 μF, connected to a BioRad Pulse Controller Plus with resistance settings of 50 to 200 Ω. Following electroporation the cells were immediately diluted in 0.9 ml of pre-reduced and pre-warmed Columbia broth with 1 mM MgCl2. An aliquot was diluted and plated on non-selective media to quantify the viable count of surviving bacteria. The remaining culture was incubated anaerobically for five hours without agitation at 37°C then plated on Columbia agar with the appropriate antibiotic. Routine electroporation controls included samples not subjected to electroporation or subjected to electroporation in the absence of plasmid DNA, and samples subjected to electroporation with the control plasmid pHS19 that lacks the fusobacterial replicon from pFN1. Antibiotic concentrations twice that required to inhibit growth of the test strain were used in the selective media. All reagents and consumables were equilibrated in the anaerobic chamber for at least 12 hours before use, and all procedures except the centrifugation and electroporation were conducted in the anaerobic chamber.

Transformants were subcultured and maintained on selective media, unless otherwise noted. Plasmid DNA from representative transformants was analyzed by the size of restriction endonuclease digested DNA fragments visualized on 0.8% agarose gels under ultraviolet illumination, to confirm the presence of the expected plasmid. Transformation efficiency was calculated as the number of transformants per microgram of plasmid DNA, and the transformation frequency was calculated as the number of transformants/number of surviving bacteria.

Plasmid Stability Assays

The stability of pHS17, pHS23 and pHS30 in F. nucleatum ATCC 23726 was examined over 100 generations of growth in liquid cultures without selection. Initial overnight cultures of F. nucleatum transformants were grown in liquid media with antibiotic selection, then diluted and grown in liquid media without antibiotics over ten days passing duplicate cultures twice a day. On days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10, an aliquot was diluted, plated on agar media without antibiotics to enable growth of colonies regardless of plasmid content. Fifty individual colonies from those recovered under non-selective conditions were patched onto agar media with and without antibiotics to differentiate colony-forming units that harbor the plasmid from those in which the plasmid was lost, as a quantitative measure of segregational stability. Representative colonies from each time point were subcultured and plasmid preparations were examined by visualization of restriction endonuclease digested plasmid on agarose gels as a measure of structural stability.

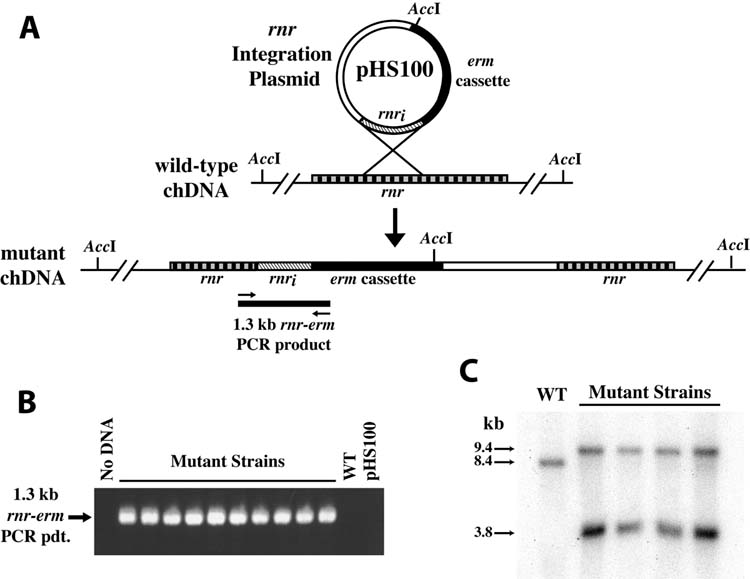

Targeted Integration Mutagenesis

The rnr gene, a 2104 bp ORF predicted to encode the exoribonuclease RNase R, was targeted for mutagenesis. The rnr gene was initially identified in F. nucleatum ATCC 10953 using preliminary sequence data obtained from Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center (BC-HGSC) website at http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu. A 731 bp fragment of rnr from F. nucleatum ATCC 23726, corresponding to bp from 782 to 1513 of the rnr ORF, was amplified by PCR using IP1 and IP2 primers (Table 1). The PCR product was confirmed by restriction endonuclease mapping, restricted with XhoI and ClaI, then ligated to comparably digested pHS19, a suicide plasmid lacking a fusobacterial replicon. The resulting plasmid pHS100 (Table 1) was propagated in E. coli DH5α using routine techniques. Cesium chloride-column purified pHS100 was used to electroporate F. nucleatum ATCC 23726, as described above. Putative transformants were selected and subcultured on media with clindamycin. Chromosomal DNA from the transformants was subjected to PCR and Southern blot analysis. The primers used for PCR analysis were designed to yield a PCR amplicon only if the integration plasmid recombined as predicted into the chromosomal rnr gene. The forward primer, PA1, was specific to sequence in the rnr gene located upstream of the rnr gene fragment used in the integration plasmid; the reverse primer was specific to the erythromycin resistance cassette present in the integration plasmid. For Southern blot analysis, chromosomal DNA was digested with AccI, subjected to gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose, then probed with a PCR-amplified 32P- radiolabelled rnr gene probe, as previously described (23, 25). PCR primers used for amplification of the rnr probe, which corresponded to bp 170 to 1842 of the rnr gene, were the SA1 and SA2.

RESULTS

Transformation of fusobacterial host strains

To identify a host strain with improved transformation efficiency as compared to F. nucleatum ATCC 10953, we examined the transformability of laboratory and clinical isolates of fusobacteria (Table 1) with the shuttle plasmid pHS17. We used pHS17 DNA isolated from a previously transformed strain of F. nucleatum ATCC 10953 in these studies because plasmid DNA from a homologous source is more efficient in transformation (24). Of the nine strains of F. nucleatum tested, only ATCC 23726 yielded antibiotic resistant colonies. The transformants of ATCC 23726 harbored plasmid DNA consistent in size and restriction endonuclease mapping with pHS17 (data not shown). Plasmid preparations from untransformed cultures of ATCC 23726 yielded no DNA, indicating the lack of detectable native plasmids in this strain. In contrast, ATCC 10953 possesses the native plasmid pFN3. Thus, in transformants of ATCC 10953 both pHS17 and pFN3 are evident (data not shown), indicating their compatibility in this host strain. Attempts to transform other fusobacterial species, including F. periodonticum, F. varium, F. necrophorum and F. mortiferum were unsuccessful.

These results described above indicate a high degree of strain and species specificity on transformation in fusobacteria. A likely basis for this specificity is the existence of restriction-modification systems in fusobacteria. Consistent with this hypothesis, our analyses comparing plasmid DNA from homologous versus heterologous strains confirmed differences in transformation efficiency. The transformation efficiency of heterologous DNA isolated from E. coli (pHS17Ec) or homologous DNA isolated from F. nucleatum transformants (pHS1710953, pHS1723726) was evaluated in F. nucleatum ATCC 23726. Transformation with homologous plasmid DNA was consistently more efficient as compared to the heterologous plasmid DNA. The highest transformation efficiency, 2.6 × 104 CFU/μg DNA, was found using pHS1723726 derived from a transformant of the homologous strain. The transformation efficiency of pHS1723726 was 65- to 100-fold greater than pHS17Ec, whereas the transformation efficiency of pHS1710953 was only 2- to 10-fold greater than that of pHS17Ec (data not shown). These findings are consistent with the interpretation that plasmid DNA isolated from the fusobacterial strains has been modified by native restriction-modification systems, and underscore the significance of these systems as barriers to transformation.

Second generation pFN1-based shuttle plasmids

The first generation shuttle plasmid pHS17 was constructed by cloning the native F. nucleatum plasmid pFN1 and an erythromycin resistance cassette into a pBluescript (Δbla) backbone (24). Plasmid properties that may affect transformation efficiency include size, DNA composition and the specific genes expressed. We constructed and tested plasmid derivates of pHS17 as a strategy to eliminate non-essential regions of DNA and to utilize an alternative resistance determinant predicted to function in F. nucleatum. These studies led to the construction of two second generation E. coli – F. nucleatum shuttle plasmids, pHS23 and pHS30 (Table 1), as described below.

To identify regions of non-essential DNA in pHS17, we generated deletions within the pFN1 portion of the pHS17 shuttle plasmid. pFN1 possesses an ori upstream of a plasmid replication protein gene homologue (repA) as well as a relaxase protein gene homologue (rlx) (24). pFN1 is predicted to be an iteron-regulated theta replicating plasmid based on homology (2, 3) and the structure of the ori (24). Because a relaxase protein is not required for theta replication, we hypothesized that the pFN1 rlx is non-essential. To test this, pHS23 was constructed from pHS17 by deletion to eliminate the pFN1 rlx (Table 1, Figure 1). As predicted, electroporation of F. nucleatum ATCC 23726 with pHS23 yielded transformants, and plasmid DNA isolated from the transformants was consistent with pHS23 by restriction endonuclease mapping. In contrast, electroporation with pHS25 (Table 1), which lacks the pFN1 ori and 5′ region of the repA gene, did not yield transformants. These data confirmed that the pFN1 rlx gene is not required for replication and implied that the pFN1 ori and/or repA gene are required for replication in F. nucleatum.

The shuttle plasmid pHS30 was generated to test the ability of a catP gene to confer resistance to chloramphenicol in F. nucleatum. pHS30 possesses the Clostridium perfringens catP gene, a ColE1 ori and the pFN1 fragment from pHS23 encoding the fusobacterial ori and repA gene (Table 1, Figure 1). Chloramphenicol resistant transformants of F. nucleatum ATCC 23726 were isolated, and confirmed to harbor plasmid DNA consistent with pHS30 based on restriction endonuclease mapping. Small background colonies were evident when transformants were selected for on media with chloramphenicol. However, the use of the chloramphenicol analog, thiamphenicol, for selection in F. nucleatum eliminated the background problem as noted for Clostridium spp. (J. I. Rood, personal communication). The catP gene is the second selectable marker shown to function in F. nucleatum.

Transformation efficiency and plasmid stability of second generation shuttle plasmids

We examined the relative efficiency of transformation of the pFN1-based shuttle plasmids by comparing the recovery of transformants of F. nucleatum ATCC 23726 following electroporation with the three shuttle plasmids, all of heterologous origin. The pHS17, pHS23 and pHS30 plasmid DNA isolated from E. coli was used at concentrations of 1 and 2.5 micrograms per electroporation. Both pHS23 and pHS30 demonstrated dramatically improved transformation efficiencies as compared to pHS17 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Transformation of F. nucleatum ATCC 23726 with Shuttle Plasmids of Heterologous Origin1

|

# of Transformants2 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid | DNA Conc. | Exp. #1 | Exp. #2 | Average | Average Transformation Efficiency3 | Fold Increase in Average # Transformants4 |

| pHS17 | 1 μg | 102 | 106 | 104 | 1.0 X 102 | |

| 2.5 μg | 91 | 422 | 257 | 1.0 X 102 | ||

| pHS23 | 1 μg | 1,800 | 10,500 | 6,150 | 6.2 X 104 | ↑ 59 X |

| 2.5 μg | 4,800 | 41,900 | 23,350 | 9.3 X 103 | ↑ 91 X | |

| pHS30 | 1 μg | 74,550 | 224,050 | 149,300 | 1.5 X 106 | ↑ 1435 X |

| 2.5 μg | 179,750 | 256,600 | 218,175 | 0.87 X 106 | ↑ 849 X | |

| pHS19 | 1 μg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2.5 μg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

The plasmid DNA used in these studies was isolated from the heterologous host, E. coli DH5α.

Electroporation was conducted in two independent experiments with 100 microliters of F. nucleatum ATCC 23726 cells at 2.5 kV and 100 Ohms. Shuttle plasmid DNA of 1 μg was added in a volume ranging from 1.6 to 3.9 λ, and of 2.5 μg the volume ranged from 4.0 to 9.6 λ.

Transformation efficiency is defined as the number of transformants/microgram of DNA.

Increase in recovery of transformants as compared to the same concentration of pHS17 DNA.

Plasmid stability was examined in representative F. nucleatum ATCC 23726 transformants harboring pHS17, pHS23 or pHS30. The strains were passed for 100 generations in liquid culture without selection, and colonies were recovered on non-selective agar media after each ca. 20 generations. To test for plasmid carriage phenotypically, fifty colonies from each time point were patched onto duplicate plates with and without antibiotic selection. All of the isolates from each time point grew on media with and without antibiotic, indicating that the plasmids are segregationally stable. Analysis of plasmids recovered from the stability study isolates by restriction endonuclease mapping confirmed the phenotypic analysis and failed to yield any evidence of structural instability. Thus, all of the pFN1-based plasmids demonstrated a high degree of stability.

Targeted chromosomal mutagenesis

The disruption of chromosomal genes is critical in molecular analyses of gene function. We used pHS19, which does not replicate in F. nucleatum, as a suicide or integration vector for chromosomal mutagenesis. We targeted a F. nucleatum homologue to an rnr gene (ribonuclease R, 2104 bp; 28% identity/41% similarity to Shigella flexneri RNase R [previously designated VacB]), which was initially identified in the genome sequence of F. nucleatum ATCC 10953. The homologous rnr gene was identified in F. nucleatum ATCC 23726 and a 731 bp fragment from the 5′ region of the gene was amplified by PCR from ATCC 23726 chromosomal DNA. This fragment was cloned into pHS19 using restriction enzyme sites introduced in the PCR primers, and the resulting rnr integration plasmid used to transform ATCC 23726. A total of 13 putative mutants were isolated on selective agar from four separate electroporation reactions, with an average mutagenesis efficiency of 0.6 + 0.3 mutants per microgram of DNA. Plasmid preparations failed to yield evidence of plasmid DNA in these strains. Chromosomal DNA preparations from 11 of the putative mutants were used in Southern blot and/or PCR analyses (Figure 2). For analysis by PCR, primers were designed to hybridize to a region of the rnr gene upstream of the fragment cloned into the rnr integration plasmid, and to the 5′ region of the erm cassette (Figure 2A). The appropriately sized DNA fragment was amplified from chDNA template of the mutant strains (Figure 2B); and as predicted, was not amplified from parental strain chDNA template (Figure 2B, WT) or the rnr integration plasmid template (Figure 2B, pHS100). Southern blot analysis conducted using AccI-restricted chDNA probed with the radiolabeled rnr gene is seen in Figure 2C. A single hybridizing band is evident in the parental chDNA (Figure 2C, WT), as predicted by the lack of an AccI site in the parental rnr gene. In contrast, two hybridizing bands are evident in the mutant strain chDNA (Figure 2C), consistent with the introduction of a single AccI site from the rnr integration plasmid (Figure 2A). In all of the mutants analyzed, the plasmid appears to have integrated into the rnr gene in a single crossover event. These results demonstrate targeted chromosomal mutagenesis by homologous recombination of a suicide vector in F. nucleatum ATCC 23726.

Figure 2. Targeted mutagenesis of the F. nucleatum ATCC 23726 chromosomal rnr gene.

The rnr integration plasmid pHS100 was constructed with a fragment of the rnr gene to provide a region of DNA enabling homologous recombination of the suicide plasmid into the F. nucleatum chromosomal rnr gene (Panel A). Analysis of the mutants (Panels B and C) was consistent with this prediction. A: Schematic diagram of the integration plasmid pHS100, wild-type and mutant chromosomal structure. The position of primers and the predicted PCR amplicon specific to the chromosomal insertion of pHS100 are indicated. The position of the primers (SA1 and SA2) and the predicted 1.3 kb amplicon are indicated. Note also integration of the plasmid introduces a unique AccI site between the 5′ and 3′ ends of the rnr gene. B: PCR analysis revealed the presence of the 1.3 kb amplicon specific to the chromosomal insertion with the mutant strain chromosomal DNA. As predicted, no PCR product was evident in the absence of DNA template (No DNA), or when using either the parental chromosomal DNA (WT) or pHS100 as template (IP). C: Southern blot of AccI-digested chromosomal DNA from the parental strain ATCC 23726 (WT) and representative mutant strains was probed with a radiolabeled rnr DNA probe. In the parental wild type chromosomal DNA a single AccI band is detected with the rnr probe, as predicted due to the lack of an AccI site in the wild type rnr gene. In contrast, two hybridizing DNA bands are evident in the chromosomal DNA of the mutant strains, consistent with the introduction of a unique AccI site present in the rnr integration plasmid. The approximate molecular mass of the bands is indicated on the left.

DISCUSSION

The lack of genetic tools for use with F. nucleatum has hampered progress in delineating relevant properties and understanding the role of this species in biofilm ecology and pathogenesis. We previously reported use of the first generation shuttle plasmid pHS17 in transforming a single strain of F. nucleatum, albeit at low efficiency (24). In this investigation we focused on refinements in key aspects of gene transfer, host strain selection and vector design, to facilitate molecular analysis including chromosomal integration mutagenesis. We document in these studies the improved transformation with a second host F. nucleatum strain, ATCC 23726, and two second generation shuttle plasmids, pHS23 and pHS30. Using this highly transformable strain, we document targeted mutagenesis of a chromosomal F. nucleatum gene using a suicide vector, pHS19. Together these approaches provide an important foundation for molecular analysis in F. nucleatum.

The two strains we have transformed to date are ATCC 10953, a ssp. polymorphum strain for which the genome sequence is available, and ATCC 23726, an unsequenced ssp. nucleatum strain. Distinct restriction endonuclease activities in different strains of F. nucleatum are well documented (29, 30, 34) and our data on the effects of homologous versus heterologous DNA sources are consistent with a role for native restriction endonucleases as a barrier to transformation in this species. Genomic DNA sequence analyses indicate the presence of two restriction endonuclease genes in the ssp. nucleatum strain ATCC 25586 and five in ssp. vincentii strain ATCC 49256 (34). Our analysis of the ATCC 10953 sequence indicates the existence of at least two putative restriction endonuclease genes (unpublished data). Strategies to pre-methylate vector DNA (12), or to knockout restriction endonucleases in strains amenable to transformation (25), may facilitate further advances in gene transfer systems.

The second generation pFN1-based shuttle plasmids proved to be substantially more efficient in transforming F. nucleatum ATCC 23726, with 50- to greater than 1440-fold increases in transformation efficiency when compared to pHS17. Both pHS30 and pHS23 are smaller than pHS17, but size alone is unlikely to account for the differences observed. A possible reason for the improved efficiency may relate to the loss of specific restriction endonuclease sites that are targeted by host cell restriction endonucleases in the smaller plasmids, as compared to pHS17. Interestingly, the improved efficiency of pHS30 and pHS23 was not evident with F. nucleatum ATCC 10953 (data not shown), a finding consistent with the hypothesis that the efficiency difference relates to distinct native restriction endonucleases. The smaller size of pHS30 and pHS23 may be of benefit to their use as vectors, as they may be able to accommodate larger fragments of cloned DNA. Another feature that could contribute to the efficiency of pHS30 may relate to the use of the resistance determinant catP, isolated originally from a strain of C. perfringens (1). C. perfringens and F. nucleatum are characterized by strikingly low genomic GC content, at 29 and 27%, respectively (22, 35). Differences in the promoters or codon bias may affect expression of the catP gene versus the erm determinants (32), thereby influencing the recovery of transformants. Further investigation is needed to clarify the impact of these differences on gene expression in F. nucleatum. Our studies with the pFN1-based shuttle plasmids indicate a high degree of segregational and structural stability under both selective and non-selective growth conditions. The native fusobacterial plasmid pFN1 is predicted to be a theta replicating plasmids based on sequence homology, but plasmid determinants conferring segregational stability have not been identified.

The inactivation of chromosomal genes is central to molecular analysis of microbial properties, and of particular importance to F. nucleatum in light of the emerging genomic DNA sequence data. The rnr gene, which encodes a 5′-3′ exoribonuclease, was originally identified as the vacB gene by Tn5 mutagenesis in Shigella flexneri based on reduced invasion (8, 37). In E. coli RNase R is believed to function along with a polynucleotide phosphorylase in the maintenance of ribosomal RNA quality control through the removal of defective RNAs (7). RNase R is not essential to viability, although inactivation of both the rnr and polynucleotide phosphorylase genes results in bacterial cell death (7). Further, the loss of RNase R activity in E. coli is not evident in the presence of RNase II activity (8). To our knowledge, exoribonuclease activity has not been studied in fusobacteria, and we have not detected any alteration in exoribonuclease activity in the F. nucleatum rnr mutant in comparison to the parental wild type strain (data not shown). This finding is consistent with the ability to isolate an rnr mutant in F. nucleatum, suggesting that there is overlapping exoribonuclease activity encoded by another gene. F. nucleatum is invasive (18) and although preliminary characterization of the rnr mutant suggest alterations in the invasion of an endothelial cell line, further studies are needed to clarify the phenotypic alterations. To our knowledge, the rnr mutants described here represent the first targeted mutagenesis in this species.

In conclusion, these studies document important advances in a genetic system for molecular analyses in F. nucleatum. Two strains are amenable to transformation, and the ssp. nucleatum strain ATCC 23726 is more efficiently transformed with the currently available shuttle plasmids. Two second generation pFN1-based shuttle plasmids are described; both are stably maintained in F. nucleatum and demonstrate substantially improved transformation efficiency. One of the newly described shuttle plasmids, pHS30, confers chloramphenicol resistance as a second resistance marker of use in F. nucleatum. Finally, we demonstrate the use of targeted integration mutagenesis for the disruption of a chromosomal gene in F. nucleatum ATCC 23726. These advances will facilitate analyses addressing the role of F. nucleatum in ecology and pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical assistance of Ester Lee, Charlie Cho, Heiman Ng and Salamon Lara. We thank Julian I. Rood for providing the plasmid pJIR750 and input on antibiotic selection, Ann Tanner and Mark McBride for providing F. nucleatum GXA6, and David Haake and Rob Gunsalus for review of this manuscript.

The DNA sequence of F. nucleatum ATCC 10953 was obtained from BC-HGSC website at http://www.hgsc.tmc.edu. The DNA sequencing of F. nucleatum ATCC 10953 was supported by Public Health Service grant DE013759 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research to G. Weinstock at the BCM-HGSC. This work was supported by grants from the UCLA School of Dentistry Opportunity Fund, the UCLA Academic Senate, and Public Health Service grants DE012639 and DE015348 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research to S.K.H.

References

- 1.Bannam TL, Rood JI. Clostridium perfringens - Escherichia coli shuttle vectors that carry single antibiotic resistance determinants. Plasmid. 1993;229:233–235. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benachour A, Frere J, Flahaut S, Novel G, Auffray Y. Molecular analysis of the replication region of the theta-replicating plasmid of pUCL287 from Tetragenococcus (Pediococcus) halophilus ATCC33315. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;255:504–513. doi: 10.1007/s004380050523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benachour A, Frere J, Novel G. pUCL287 plasmid from Tetragenococcus halophila (Pediococcus halophilus) ATCC 33315 represents a new theta-type replicon family of lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;128:167–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradshaw DJ, Marsh PD, Watson GK, Allison C. Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum and coaggregation in anaerobe survival in planktonic and biofilm oral microbial communities during aeration. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4729–4732. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4729-4732.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brook I, Frazier EH. Microbiology of liver and spleen abscesses. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:1075–1080. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-12-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhry R, Dhawan B, Laxmi BV, Mehta VS. The microbial spectrum of brain abscess with special reference to anaerobic bacteria. Br J Neurosurg. 1998;12:127–30. doi: 10.1080/02688699845258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng ZF, Deutscher MP. Quality control of ribosomal RNA mediated by polynucleotide phosphorylase and RNase R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6388–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1231041100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng ZF, Zuo Y, Li Z, Rudd KE, Deutscher MP. The vacB gene required for virulence in Shigella flexneri and Escherichia coli encodes the exoribonuclease RNase R. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14077–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chryssagi AM, Brusselmans CB, Rombouts JJ. Septic arthritis of the hip due to Fusobacterium nucleatum. Clin Rheumatol. 2001;20:229–31. doi: 10.1007/s100670170072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Civen R, Jousimies-Somer H, Marina M, Borenstein L, Shah H, Finegold SM. A retrospective review of cases of anaerobic empyema and update of bacteriology. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20 (Suppl 2):S224–S229. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.supplement_2.s224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaz PI, Zilm PS, Rogers AH. Fusobacterium nucleatum supports the growth of Porphyromonas gingivalis in oxygenated and carbon-dioxide-depleted environments. Microbiol. 2002;148:467–72. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-2-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donahue JP, Israel DA, Peek RM, Blaser MJ, Miller GG. Overcoming the restriction barrier to plasmid transformation of Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:1066–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dzink JL, Sheenan MT, Socransky SS. Proposal of three subspecies of Fusobacterium nucleatum Knorr 1922: Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp nucleatum subsp nov, comb nov; Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp polymorphum subsp nov, nom rev, comb nov; and Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp vincentii subsp nov, nom rev, comb nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1990;40:74–78. doi: 10.1099/00207713-40-1-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fletcher HM, Schenkein HA, Morgan RM, Bailey KA, Berry CR, Macrina FL. Virulence of a Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 mutant defective in the prtH gene. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1521–1528. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1521-1528.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gharbia SE, Shah HN. Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp fusiforme subsp nov and Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp animalis subsp nov as additional subspecies within Fusobacterium nucleatum. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:296–298. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-2-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein EJC, Summanen PH, Citron DM, Rosove MH, Finegold SM. Fatal sepsis due to a β-lactamase-producing strain of Fusobacterium nucleatum subspecies polymorphum. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:797–800. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han YW, Redline RW, Li M, Yin L, Hill GB, McCormick TS. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces premature and term stillbirths in pregnant mice: implication of oral bacteria in preterm birth. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2272–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2272-2279.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han YW, Shi W, Huang GT, Kinder Haake S, Park N-H, Kuramitsu H, Genco RJ. Interactions between periodontal bacteria and human oral epithelial cells: Fusobacterium nucleatum adheres to and invades epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3140–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3140-3146.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill GB. Preterm birth: associations with genital and possibly oral microflora. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:222–32. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holst E, Goffeng AR, Andersch B. Bacterial vaginosis and vaginal microorganisms in idiopathic premature labor and association with pregnancy outcome. J Clin, Microbiol. 1994;32:176–186. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.176-186.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jousimies-Somer H, Savolainen S, Mäkitie A, Ylikoski J. Bacteriologic findings in peritonsillar abscesses in young adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16 (Suppl 4):S292–298. doi: 10.1093/clinids/16.supplement_4.s292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapatral V, Anderson I, Ivanova N, Reznik G, Los T, Lykidis A, Bhattacharyya A, Bartman A, Gardner W, Grechkin G, Zhu L, Vasieva O, Chu L, Kogan Y, Chaga O, Goltsman E, Bernal A, Larsen N, D'Souza M, Walunas T, Pusch G, Haselkorn R, Fonstein M, Kyrpides N, Overbeek R. Genome sequence and analysis of the oral bacterium Fusobacterium nucleatum strain ATCC 25586. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:2005–18. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.7.2005-2018.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinder Haake S, Wang X. Cloning and expression of fomA, the major outer membrane protein gene from Fusobacterium nucleatum T18. Arch Oral Biol. 1997;42:19–24. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(96)00105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinder Haake S, Yoder SC, Attarian G, Podkaminer K. Native plasmids of Fusobacterium nucleatum: Characterization and use in development of genetic systems. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1176–1180. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.1176-1180.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kinder SA, Badger JL, Bryant GO, Pepe JC, Miller VL. Cloning of the YenI restriction endonuclease and methyltransferase from Yersinia enterocolitica serotype 08 and construction of a R-M+ mutant. Gene. 1993;136:271–275. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90478-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolenbrander PE. Oral microbial communities: biofilms, interactions, and genetic systems. Ann Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:413–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kononen E. Development of oral bacterial flora in young children. Ann Med. 2000;32:107–12. doi: 10.3109/07853890009011759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kononen E, Kanervo A, Salminen K, Jousimies-Somer H. Beta-lactamase production and antimicrobial susceptibility of oral heterogeneous Fusobacterium nucleatum populations in young children. Antimicrob Ag Chemother. 1999;43:1270–3. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leung DW, Lui ACP, Merilees H, McBride BC, Smith M. A restriction enzyme from Fusobacterium nucleatum 4H which recognizes GCNGC. Nucl Acid Res. 1979;6:17–25. doi: 10.1093/nar/6.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lui ACP, McBride BC, Vovis GF, Smith M. Site specific endonuclease from Fusobacterium nucleatum. Nucl Acid Res. 1979;6:1–15. doi: 10.1093/nar/6.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore WE, Moore LV. The bacteria of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 1994;5:66–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1994.tb00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Musto H, Romero H, Zavala A. Translational selection is operative for synonymous codon usage in Clostridium perfringens and Clostridium acetobutylicum. Microbiology. 2003;149:855–63. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nyfors S, Kononen E, Syrjanen R, Komulainen E, Jousimies-Somer H. Emergence of penicillin resistance among Fusobacterium nucleatum populations of commensal oral flora during early childhood. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:107–12. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts RJ, Vincze T, Posfai J, Macelis D. REBASE--restriction enzymes and DNA methyltransferases. Nucl Acid Res. 2005;33(Database Issue):D230–2. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimizu T, Ohtani K, Hirakawa H, Ohshima K, Yamashita A, Shiba T, Ogasawara N, Hattori M, Kuhara S, Hayashi H. Complete genome sequence of Clostridium perfringens, an anaerobic flesh-eater. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:996–1001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022493799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RL., Jr Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:134–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tobe T, Sasakawa C, Okada N, Honma Y, Yoshikawa M. vacB, a novel chromosomal gene required for expression of virulence genes on the large plasmid of Shigella flexneri. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6359–67. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6359-6367.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tunér K, Lindqvist L, Nord CE. Purification and properties of a novel β-lactamase from Fusobacterium nucleatum. Antimicrob Ag Chemother. 1985;27:943–947. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.6.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watts DH, Krohn MA, Hillier SL, Eschenbach DA. The association of occult amniotic fluid infection with gestational age and neonatal outcome among women in preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:351–7. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ximenez-Fyvie LA, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Comparison of the microbiota of supra- and subgingival plaque in health and periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:648–57. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027009648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]