Abstract

Study design: Case report Objective: To report an unusual case of cauda equina syndrome following penetrating injury to the lumbar spine by wooden fragments and to stress the importance of early magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in similar cases. Summary of background data: A 22-year-old girl accidentally landed on wooden bannister and sustained a laceration to her back. She complained of back pain but had fully intact neurological function. The laceration in her back was explored and four large wooden pieces were removed. However 72 h later, she developed cauda equina syndrome. MRI demonstrated the presence of a foreign body between second and third lumbar spinal levels following which she underwent emergency decompressive laminectomy and the removal of the multiple wooden fragments that had penetrated the dura. Results: Post-operatively motor function in her lower limbs returned to normal but she continued to require a catheter for incontinence. At review 6 months later, she was mobilising independently but the incontinence remained unchanged. Conclusion: There are no reported cases in the literature of wooden fragments penetrating the dura from the back with or without the progression to cauda equina syndrome. The need for a high degree of suspicion and an early MRI scan to localise any embedded wooden fragments that may be separate from the site of laceration is emphasized even if initial neurology is intact.

Keywords: Penetrating injury, Cauda equina, Wood

Introduction

Penetrating injuries to the spine, although less common than blunt trauma from motor vehicle accidents, are important causes of injury to the spinal cord [1, 2, 8, 12, 13, 18]. They are essentially of two varieties—gunshot or stab wounds. Gunshot injuries to the spine are more commonly described and are associated with a higher incidence of neurological damage. On the contrary, the prognosis is better in stab wounds where surgery plays a greater role [9, 12, 14, 16, 18]. Very few case reports have been published on the onset of cauda equina syndrome (CES) following stab wounds. Injuries with sharp knifelike objects and rarely glass have been known to cause stab wounds to the spine [1, 10, 13, 14, 17]. However, there are no reports in the literature of penetrating injury by wood to the cord or cauda equina. We report a unique case of CES that developed in a patient almost 72 h following a penetrating injury to her back by a large wooden fragment.

Case history

A 22-year-old hairdresser accidentally slipped from the top of the stairs on to the wooden bannister which broke and as she landed at the bottom of the stairs, a piece of the wood caused a laceration to her back at the upper lumbar paraspinal region. She was taken to the nearby hospital where an open laceration to the area was found. She was complaining of severe back pain but had intact neurology in her legs. The wound was explored and debrided and four large pieces of wood were removed following which she was commenced on antibiotics. Her back pain persisted and 72 h later, she started complaining of incontinence with bilateral paraesthesia and pain down her legs. On examination, she had mildly reduced power (4/5) distally in both legs with reduced sensation in her perineum.

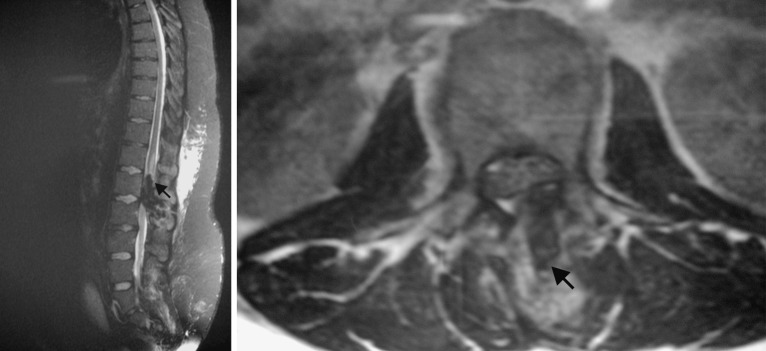

She was transferred to the Neurosurgical unit and a MRI scan of the thoracolumbar region (Fig. 1) was taken. This revealed an area of low signal intensity between the soft tissues extending towards the spinal canal into the conus at the level of the second and third lumbar spines (L 2 and L 3) with a high signal in the cord above. No obvious spinal haematoma was present. She underwent an emergency decompressive laminectomy of L 2 and L 3 with removal of several fragments of wood. At surgery, the spinous process and right hemilamina of L 2 were noted to be fractured and multiple wooden fragments were found to have entered the spinal canal (Fig. 2) penetrating the dura in the midline causing contusion and division of some of the nerve roots of the conus. These wooden pieces were carefully removed using the microscope, the dura repaired and a closed drainage system left in. Swabs for microbiological examination were obtained from the surgical site and post-operatively prophylactic intravenous cefuroxime 750 mg, thrice a day for the next 7 days were commenced. She was advised strict bed rest in supine position for 5 days while the drain was left in situ. Over this period of time, the pain and weakness in her legs resolved completely but she continued to have numbness in the perineal region and continued to require the urinary catheter. A repeat post-operative MRI scan demonstrated the high signal in the cord as before with no residual foreign body in the canal. At discharge the wound appeared satisfactory and she was mobilising independently. When reviewed 6 months later, she was otherwise asymptomatic apart from persistent altered sensation in her perineal area.

Fig. 1.

T 2 weighted Sagital MRI of the lumbar spine (left) demonstrates the wooden piece as an area of low signal intensity (arrow) within the soft tissues, extending into the spinal canal with an area of high signal in the cord above. T 2 weighted axial MRI (right) shows the wooden piece to have penetrated the theca on the left side

Fig. 2.

Per-operative view (left) demonstrates the wooden piece within the spinal canal (arrows) with size of the multiple wooden fragments demonstrated (right)

Discussion

The most widely reported cause of penetrating injury to spine is gunshot injury [1, 2, 8, 12, 13, 15, 18] with relatively few case reports describing injuries by glass or knifelike objects [1, 10, 13, 17]. Wooden foreign bodies have been reported to penetrate the cranium, orbit, face and limbs [3, 6]. However to our knowledge, there are no reports in the literature of PI to the spine by wooden fragments with or without development of CES. The only remote resemblance to our case is that by Lunawat et al. [9] who reported the presence of tiny pieces of wood in the spinal canal of an 18-year-old man who presented insidiously with weakness in his legs and who had suffered a PI to his abdomen 6 years ago.

Our case is unique due to several reasons. It is the first report of a penetrating injury by wooden fragments into the lumar spinal canal producing CES. The mechanism of injury was the direct force of the sharp wooden fragment penetrating the upper lumbar paraspinal region. We believe that after piercing the skin and subcutaneous tissue, the piece of wood probably fragmented. While some of the fragments remained superficially in the deep subcutaneous tissue overlying the thoracolumbar fascia, others were pushed towards the spinous process and right hemilamina of L 2 which were fractured and subsequently the wooden fragments pierced the dura contusing the nerve roots of the conus. What is interesting is that she developed CES almost 72 h following the injury. Whether the fragments actually moved into the canal later as a result of her movement in bed following the initial wound debridement or whether she developed oedema at the site of nerve root injury is unknown.

We found MRI scan very useful to demonstrate and localise the foreign body and also to exclude any intra- or extradural haematoma or contusion in the cord or cauda equina. In our case some contusion was demonstrated in the cord (Fig. 1). Previous reports of penetrated wooden pieces into the neck or extraspinal areas of the body have commented on the risk of misinterpretation of CT appearance of wood which appears as an area of high attenuation [3, 6]. Wood is highly echogenic and shows clear acoustic shadowing on sonography [10]. MRI is a useful adjunct to both CT and sonography for the detection of non-metallic foreign bodies such as wood [15].

Surgery in PI is indicated for progressive neurological deficits, persistent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak or for incomplete neurologic deficits with radiological evidence of compression [5]. However, surgery at the cauda equina, in such cases, may not be easy due to the dural tear associated with impingement of the foreign body with the contused nerve roots. In our patient urgent surgery was necessary as she developed progressive neurological deficit leading to CES with radiological evidence of a large foreign body causing thecal compression. Post-operatively, we took the extra precaution to prevent CSF leak from the wound by advising the patient a strict bed rest for 5 days. In our institute we advise 3–5 days of strict bed rest for patients with unintentional dural tears during Lumbar spinal surgery. This has been the practise by others too [19]. We do not routinely prescribe antibiotics for such cases. However, given the nature of this particular case, we decided to use prophylactic antibiotics in spite of negative bacteriological results. Incidentally it has been claimed that extraspinal sepsis is much more common than spinal (CSF) infection following PI to the spine [5]. We did not use methylprednisolone as there is no convincing evidence to suggest any advantage, and moreover there have been reports of myopathy following the administration of methylprednisolone in patients with acute spinal injury [7, 11].

Finally, neurological recovery from injury to the cauda equina is unpredictable and may be influenced by several factors [4] such as patient age, energy transfer to the neurovascular structures and timing of neural decompression, although the latter is debated [12, 14, 15]. Late motor recovery has been reported to occur after PI to the cauda equina up to 16 years after injury in one study [8]. Our patient had excellent symptomatic relief of her back and bilateral leg pain following surgery with resolution of the motor weakness in her legs. However, the perineal numbness has persisted and we would have to wait and see if this improves in future.

Conclusion

Penetrating wound to the upper lumbar spine is common with gunshot injuries but has never been described with wooden fragments. MRI scan provides excellent visualisation of the foreign body and also helps to exclude any underlying spinal haematoma or contusion. For all similar cases where a laceration containing wood is found, the authors recommend a high index of suspicion and a MRI scan must be performed early to look for separate fragments of wood deeper down. Neural decompression and removal of the foreign bodies should be performed to prevent neurological deterioration, infection and possible CSF leak.

References

- 1.Baghai P, Sheptak PE. Penetrating spinal injury by a glass fragment: case report and review. Neurosurgery. 1982;11(3):419–422. doi: 10.1097/00006123-198209000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cybulski GR, Stone JL, Kant R. Outcome of laminectomy for civilian gunshot injuries of the terminal spinal cord and cauda equina: review of 88 cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;24(3):392–397. doi: 10.1097/00006123-198903000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ginsberg LE, Williams DW, III, Mathews VP. CT in penetrating craniocervical injury by wooden foreign bodies: reminder of a pitfall. Am J. 1993;14(4):892–895. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrop JS, Hunt GE Jr, Vaccaro AR (2004) Conus medullaris and cauda equina syndrome as a result of traumatic injuries: management principles. Neurosurg Focus 15, 16(6):e4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Heary RF, Vaccaro AR, Mesa JJ, Balderston Thoracolumbar infections in penetrating injuries to the spine. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996;27(1):69–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imokawa H, Tazawa T, Sugiura N, Oyake D, Yosino K. Penetrating neck injuries involving wooden foreign bodies: the role of MRI and the misinterpretation of CT images. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2003;30(Suppl):S145–147. doi: 10.1016/S0385-8146(02)00130-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy ML, Gans W, Wijesinghe HS, CB, et al. Use of methylprednisolone as an adjunct in the management of patients with penetrating spinal cord injury: outcome analysis (discussion 1148–1149) Neurosurgery. 1996;39(6):1141–1148. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199612000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Little J, DeLisa J. Cauda equina injury: late motor recovery. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986;67:45–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lunawat SK, Taneja DK. A foreign body in the spinal canal: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(2):267–268. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.82B2 .10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Opel DJ, Lundin DA, Stevenson KL, Klein EJ. Glass foreign body in the spinal canal of a child: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20(7):468–72. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000136894.91647.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qian T, Guo X, Levi AD, Sipski ML, et al. High-dose methylprednisolone may cause myopathy in acute spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord. 2005;43(4):199–203. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robertson DP, Simpson RK. Penetrating injuries restricted to the cauda equina: a retrospective review (discussion 269–270) Neurosurgery. 1992;31(2):265–269. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199208000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubin G, Tallman D, Sagan L, Melgar (2001) An unusual stab wound of the cervical spinal cord: a case report. Spine 15, 26(4):444–447 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Simpson RK, Jr, Venger BH, Narayan RK. Treatment of acute penetrating injuries of the spine: a retrospective analysis. J Trauma. 1989;29(1):42–46. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198901000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stauffer E, Wood R, Kelly E. Gunshot wounds of the spine The effects of laminectomy. J Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61A:389–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinmetz, Michael P, Krishnaney, Ajit A, McCormick, William, Benzel, Edward C. Penetrating spinal injuries. Neurosurg Q. 2004;14(4):217–223. doi: 10.1097/00013414-200412000-00006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thakur RC, Khosla VK, Kak VK. Non-missile penetrating injuries of the spine. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1991;113(3–4):144–148. doi: 10.1007/BF01403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Velmahos GC, Degiannis E, Hart K, Souter I, Saadia R. Changing profiles in spinal cord injuries and risk factors influencing recovery after penetrating injuries. J Trauma. 1995;38(3):334–337. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199503000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang JC, Bohlman HH, Riew KD. Dural tears secondary to operations on the lumbar spine. Management and results after a two-year-minimum follow-up of eighty-eight patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(12):1728–1732. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.80B6.8966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]