Abstract

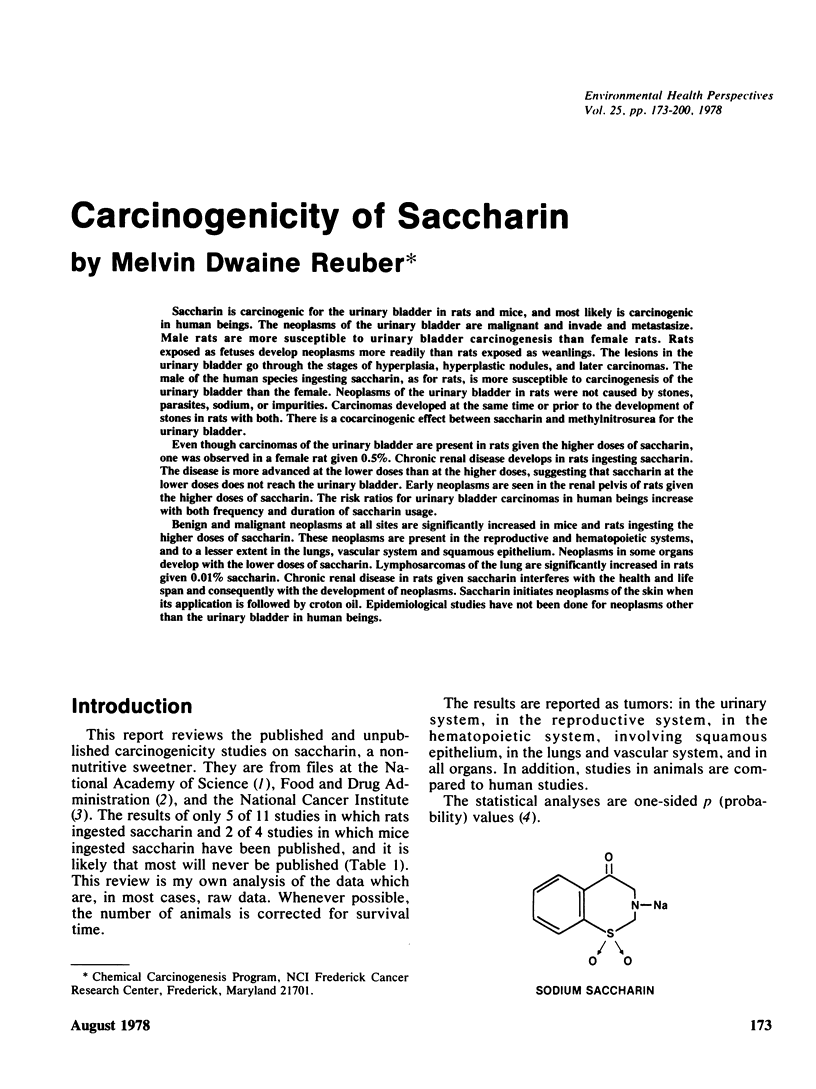

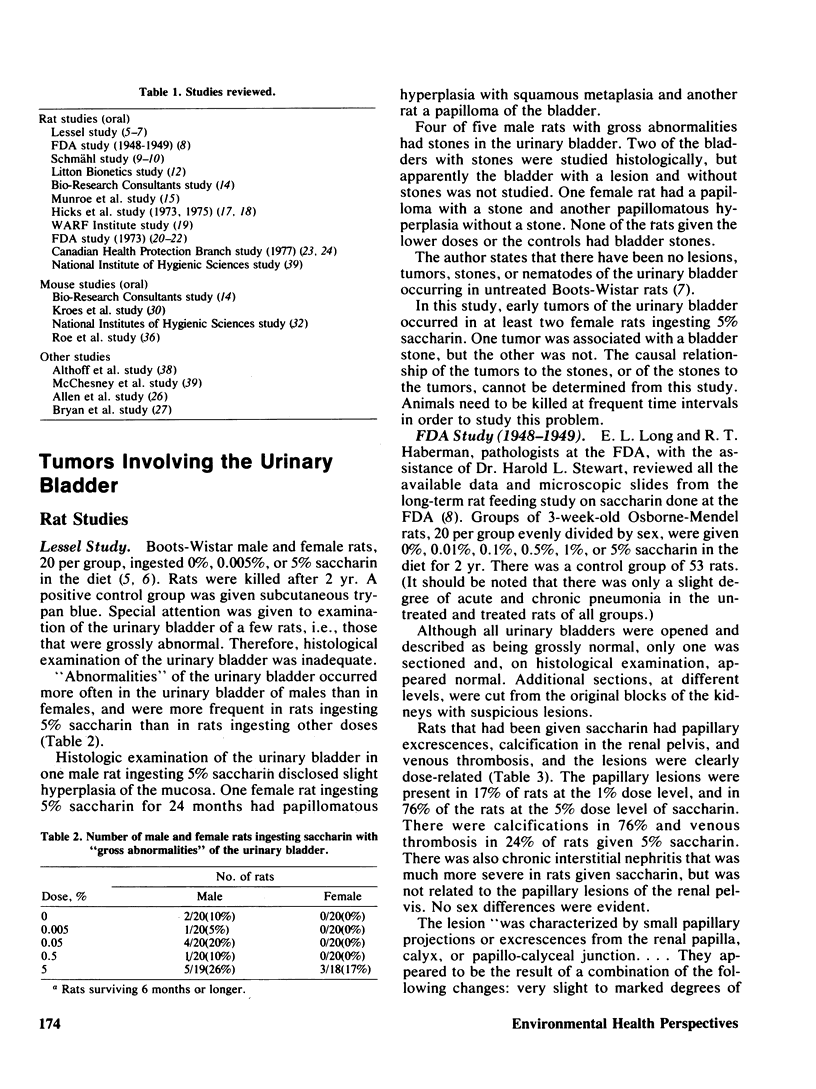

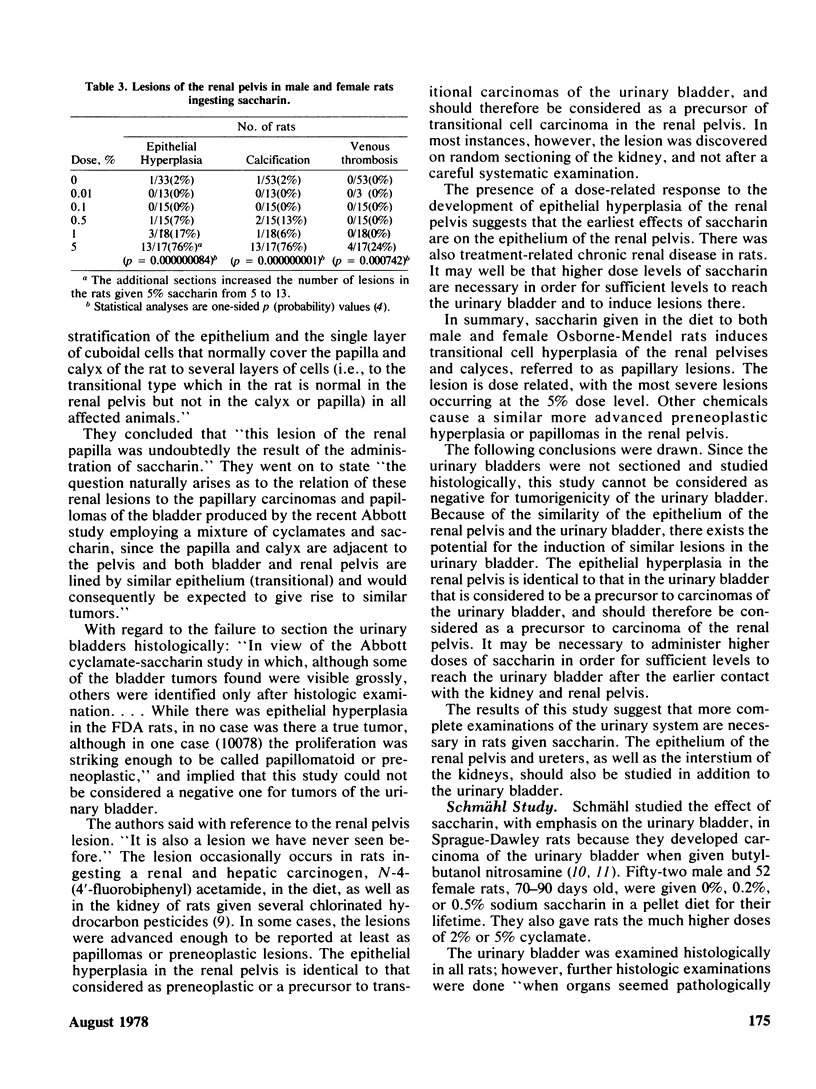

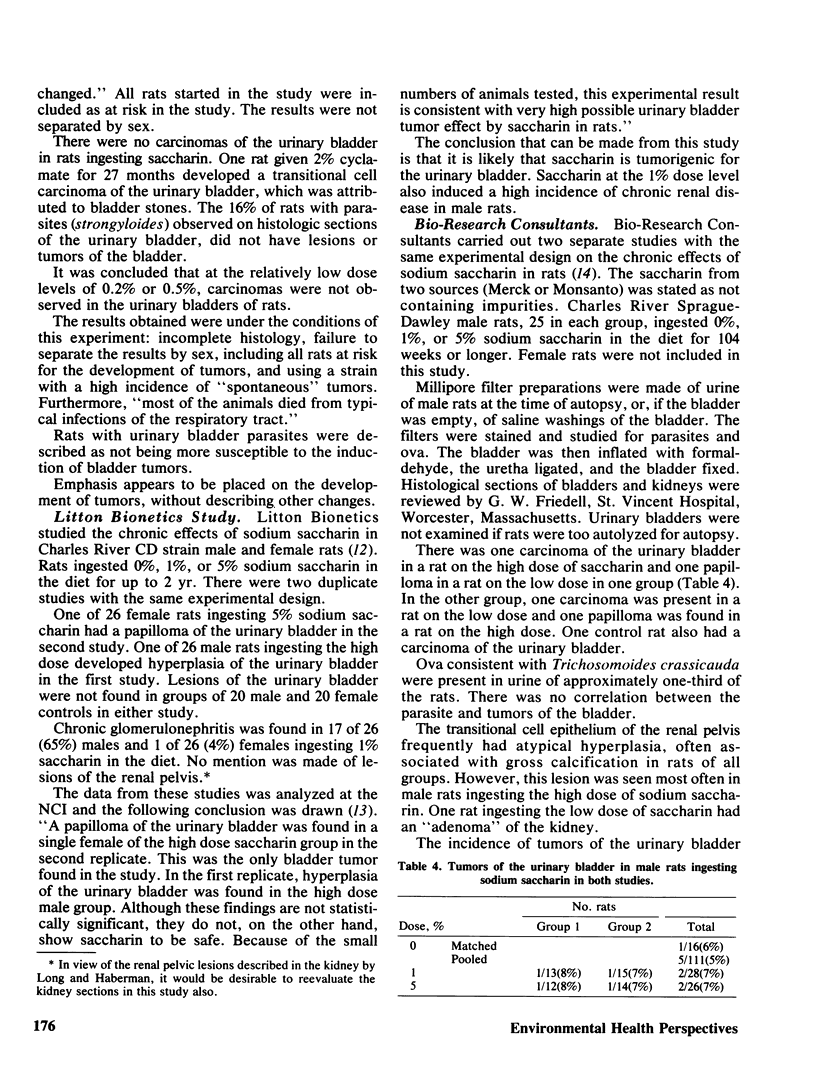

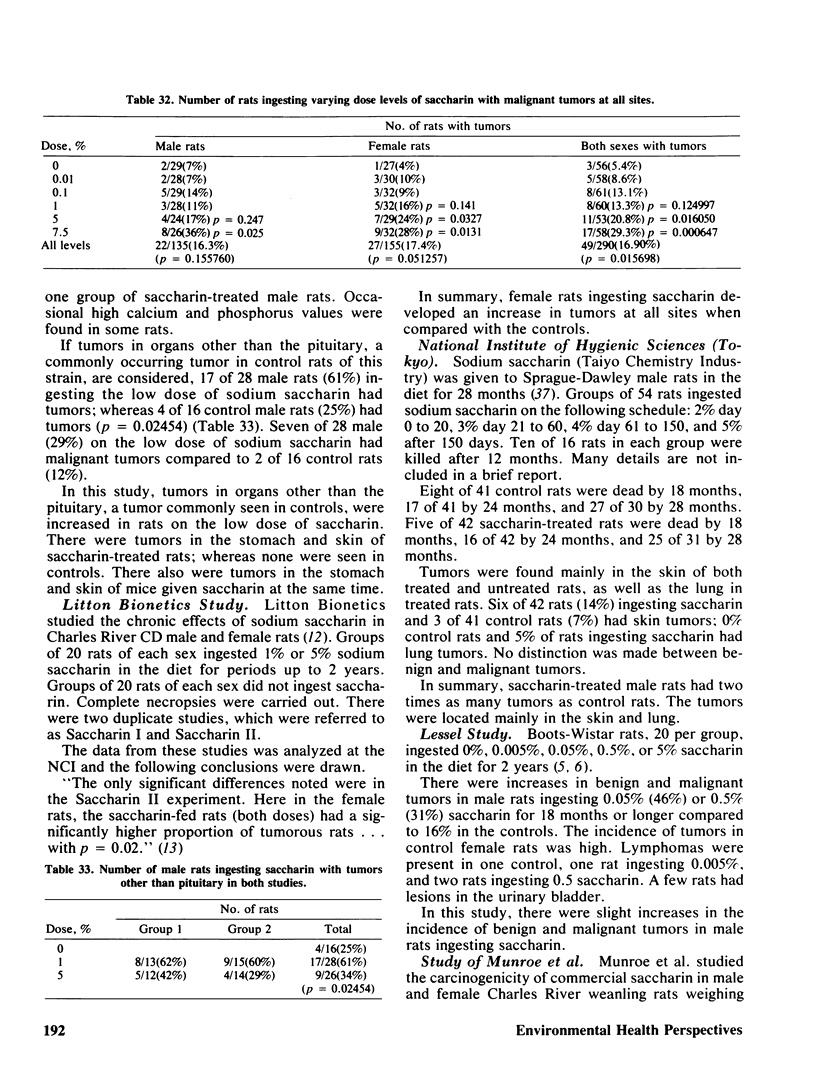

Saccharin is carcinogenic for the urinary bladder in rats and mice, and most likely is carcinogenic in human beings. The neoplasms of the urinary bladder are malignant and invade and metastasize. Male rats are more susceptible to urinary bladder carcinogenesis than female rats. Rats exposed as fetuses develop neoplasms more readily than rats exposed as weanlings. The lesions in the urinary bladder go through the stages of hyperplasia, hyperplastic nodules, and later carcinomas. The male of the human species ingesting saccharin, as for rats, is more susceptible to carcinogenesis of the urinary bladder than the female. Neoplasms of the urinary bladder in rats were not caused by stones, parasites, sodium, or impurities. There is a cocarcinogenic effect between saccharin and methylnitrosurea for the urinary bladder. Even through carcinomas of the urinary bladder are present in rats given the higher doses of saccharin, one was observed in a female rat given 0.5%. Chronic renal disease develops in rats ingesting saccharin. The disease is more advanced at the lower doses than at the higher doses, suggesting that saccharin at the lower doses does not reach the urinary bladder. Early neoplasms are seen in the renal pelvis of rats given the higher doses of saccharin. The risk ratios for urinary bladder carcinomas in human beings increase with both frequency andduration of saccharin usage. Benign and malignant neoplasms at all sites are significantly increased in mice and rats ingesting the higher doses of saccharin. These neoplasms are present in the reproductive and hematopoietic systems, and to a lesser extent in the lungs, vascular system and squamous epithelium. Neoplasms in some organs develop with the lower doses of saccharin. Lymphosarcomas of the lung are significantly increased in rats given 0.01% saccharin. Chronic renal disease in rats given saccharin interferes with the health and life span and consequently with development of neoplasms. Saccharin initiates neoplasms of the skin when its application is followed by croton oil. Epidemiological studies have not been done for neoplasms other than the urinary bladder in human beings.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ALLEN M. J., BOYLAND E., DUKES C. E., HORNING E. S., WATSON J. G. Cancer of the urinary bladder induced in mice with metabolites of aromatic amines and tryptophan. Br J Cancer. 1957 Jun;11(2):212–228. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1957.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong B., Lea A. J., Adelstein A. M., Donovan J. W., White G. C., Ruttle S. Cancer mortality and saccharin consumption in diabetics. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1976 Sep;30(3):151–157. doi: 10.1136/jech.30.3.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRYAN G. T., BROWN R. R., MORRIS C. R., PRICE J. M. IN VIVO ELUTION OF TRYPTOPHAN METABOLITES AND OTHER AROMATIC NITROGEN COMPOUNDS FROM CHOLESTEROL PELLETS IMPLANTED INTO MOUSE BLADDERS. Cancer Res. 1964 May;24:586–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batzinger R. P., Ou S. Y., Bueding E. Saccharin and other sweeteners: mutagenic properties. Science. 1977 Dec 2;198(4320):944–946. doi: 10.1126/science.337489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan G. T., Ertürk E. Production of mouse urinary bladder carcinomas by sodium cyclamate. Science. 1970 Feb 13;167(3920):996–998. doi: 10.1126/science.167.3920.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan G. T., Ertürk E., Yoshida O. Production of urinary bladder carcinomas in mice by sodium saccharin. Science. 1970 Jun 5;168(3936):1238–1240. doi: 10.1126/science.168.3936.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman W. H. Infection with Trichosomoides crassicauda as a factor in the induction of bladder tumors in rats fed 2-acetylaminofluorene. Invest Urol. 1969 Sep;7(2):154–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks R. M., Wakefield J. S., Chowaniec J. Letter: Co-carcinogenic action of saccharin in the chemical induction of bladder cancer. Nature. 1973 Jun 8;243(5406):347–349. doi: 10.1038/243347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks R. M., Wakefield J., Chowaniec J. Evaluation of a new model to detect bladder carcinogens or co-carcinogens; results obtained with saccharin, cyclamate and cyclophosphamide. Chem Biol Interact. 1975 Sep;11(3):225–233. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(75)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy G., Fancher O. E., Calandra J. C. Metabolic fate of saccharin in the albino rat. Food Cosmet Toxicol. 1972 Apr;10(2):143–149. doi: 10.1016/s0015-6264(72)80192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler I. I. Non-nutritive sweeteners and human bladder cancer: preliminary findings. J Urol. 1976 Feb;115(2):143–146. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)59104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroes R., Peters P. W., Berkvens J. M., Verschuuren H. G., de Vries T., van Esch G. J. Long term toxicity and reproduction study (including a teratogenicity study) with cyclamate, saccharin and cyclohexylamine. Toxicology. 1977 Dec;8(3):285–300. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(77)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews H. B., Fields M., Fishbein L. Saccharin: distribution and excretion of a limited dose in the rat. J Agric Food Chem. 1973 Sep-Oct;21(5):916–919. doi: 10.1021/jf60189a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkin R. M., Andersen D. W., Reynolds W. A., Filer L. J., Jr Saccharin metabolism in Macaca mulatta. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1971 Jul;137(3):803–806. doi: 10.3181/00379727-137-35671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkin R. M., Reynolds W. A., Filer L. J., Jr Placental transmission and fetal distribution of cyclamate in early human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970 Dec 1;108(7):1043–1050. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(70)90449-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROE F. J., SALAMAN M. H. Further tests for tumour-initiating activity: N, N-di-(2-chloroethyl)-p-aminophenylbutyric acid (CB1348) as an initiator of skin tumour formation in the mouse. Br J Cancer. 1956 Jun;10(2):363–378. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1956.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuber M. D. Development of preneoplastic and neoplastic lesions of the liver in male rats given 0.025 percent N-2-fluorenyldiacetamide. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1965 Jun;34(6):697–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuber M. D. Review of toxicity test results submitted in support of pesticide tolerance petitions. Sci Total Environ. 1978 Mar;9(2):135–148. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(78)90072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe F. J., Levy L. S., Carter R. L. Feeding studies on sodium cyclamate, saccharin and sucrose for carcinogenic and tumour-promoting activity. Food Cosmet Toxicol. 1970 Apr;8(2):135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0015-6264(70)80332-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmähl D. Fehlen einer kanzerogenen Wirkung von Cyclamat, Cyclohexylamin und Saccharin bei Ratten. Arzneimittelforschung. 1973 Oct;23(10):1466–1470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]