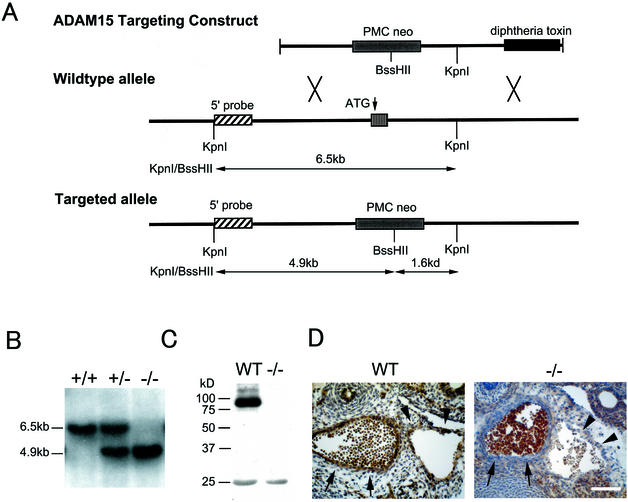

FIG. 4.

Targeted mutation of ADAM15. (A) The targeting vector is shown at the top. The targeted exon was disrupted by insertion of a pMC1neoPolyA cassette, which introduces a BssHII site that is not present in the wild-type allele. A diphtheria toxin gene cassette was added at the 3′ end of the targeting construct to select against nonhomologous recombination events. A schematic of the wild-type adam15 allele is shown in the middle. The position of the 5′ probe used for Southern blot analysis is indicated, as well as the exon that codes for the initial methionine of ADAM15, and KpnI sites. The bottom panel shows key features of the targeted allele. The BssHII site introduced into the targeted allele reduces the length of the KpnI/BssHII genomic fragment recognized by the 5′ probe from 6.5 to 4.9 kb. (B) Southern blot analysis of KpnI/BssHII-digested genomic DNA from wild-type, heterozygous adam15+/−, and homozygous adam15−/− mice. (C) Western blot analysis of heart extracts from wild-type and adam15−/− mice confirmed that ADAM15 protein expression is abolished in adam15−/− mice. (D) Sections of the descending aorta (arrows) and subcardinal vein (arrowheads) of wild-type (WT) and adam15−/− (−/−) E13.5 embryos. An immunohistochemical analysis shows staining of vascular cells in wild-type mice but not in adam15−/− mice. Scale bar, 100 μm. This finding confirms that the vascular staining pattern of anti-ADAM15 polyclonal antibodies is specific. In contrast, blood cells within the vessels are stained in both wild-type and adam15−/− mice, and therefore this staining is not specific for ADAM15. The polyclonal anti-ADAM15 antibodies used in panels C and D and in Fig. 2 were from the same bleed of a New Zealand White rabbit that was immunized with an Fc fusion protein with the ectodomain of mouse ADAM15.