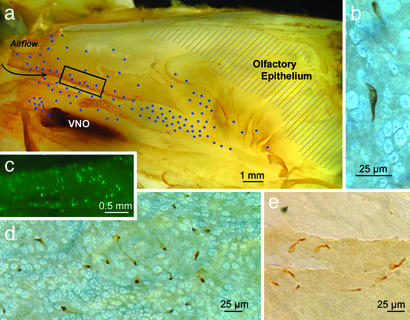

Fig. 1.

Gustducin-expressing cells in the nasal epithelium. (a) The distribution of gustducin-immunoreactive cells on the turbinates and lateral nasal wall of a 6-week-old rat plotted on a lateral view of the nasal cavity split along the sagittal plane. The blue dots indicate the relative density and location of reactive cells. The region of olfactory epithelium is indicated by shading. The dark region at the left side of the figure is the vomeronasal organ (VNO). (Scale bar, 1.0 mm.) (b) Micrograph of an immunoreactive cell in the epithelium of a whole mount is shown. The elongate cell runs obliquely through the thin epithelium. (c) Fluorescent cells in the anterior portions of the nasal cavity, just caudal to the vestibule (boxed region in a), from an adult transgenic mouse in which GFP is driven by the gustducin promoter. The distribution of these fluorescent cells is similar to that revealed by gustducin immunocytochemistry. (d) Low-power micrograph of a field of gustducin-immunoreactive cells of a rat as revealed by whole-mount immunocytochemistry. The packing density of the scattered gustducin-containing cells varies according to the region of the nose in which they lie. In rats, the maximum density is ≈300 cells per mm2. More often, the density is one order of magnitude less. Because of the convoluted nature of the nasal passageways and the variable density of gustducin-containing cells, it is difficult to give a reliable estimate of the total number of cells involved; however, in rat, the number on one side of the nose is >1,000. (e) Immunoreactive cells along the torn edge of the respiratory epithelium from a rat reacted as a whole mount. The apical portion of the cell is generally more immunoreactive (darker) than lower portions.