Abstract

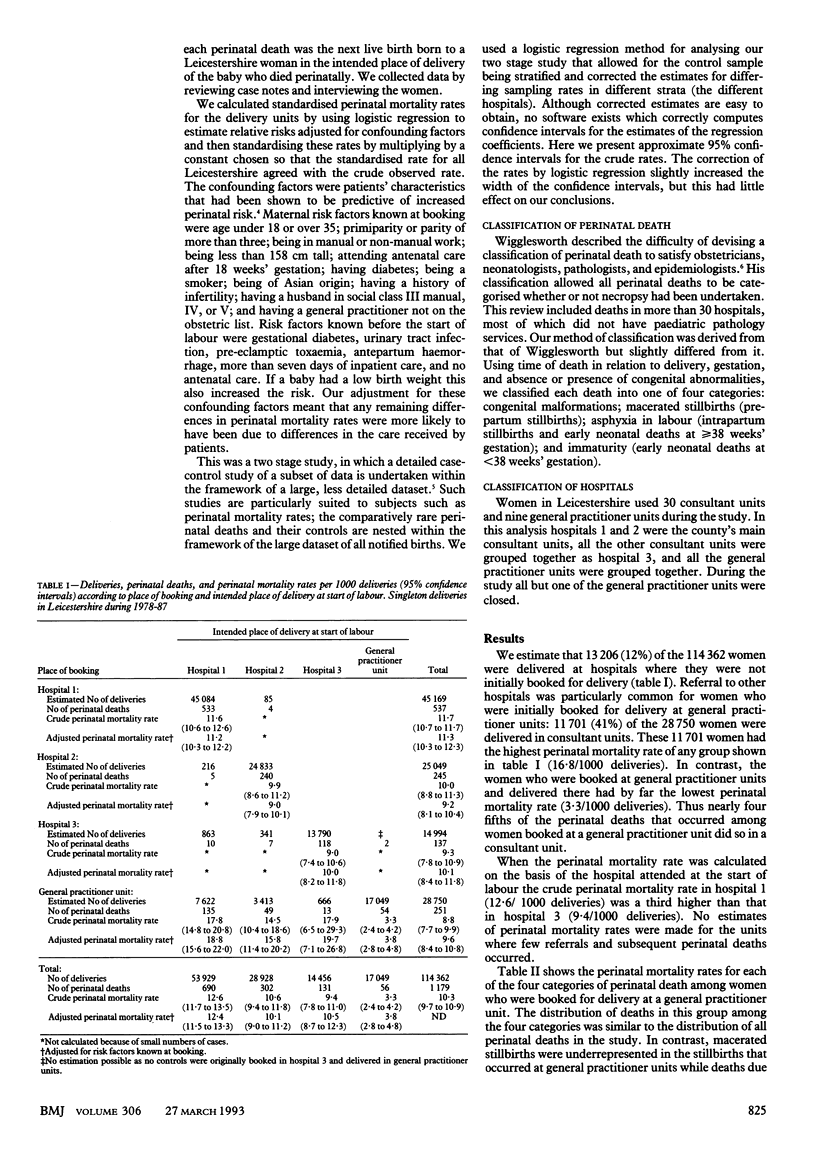

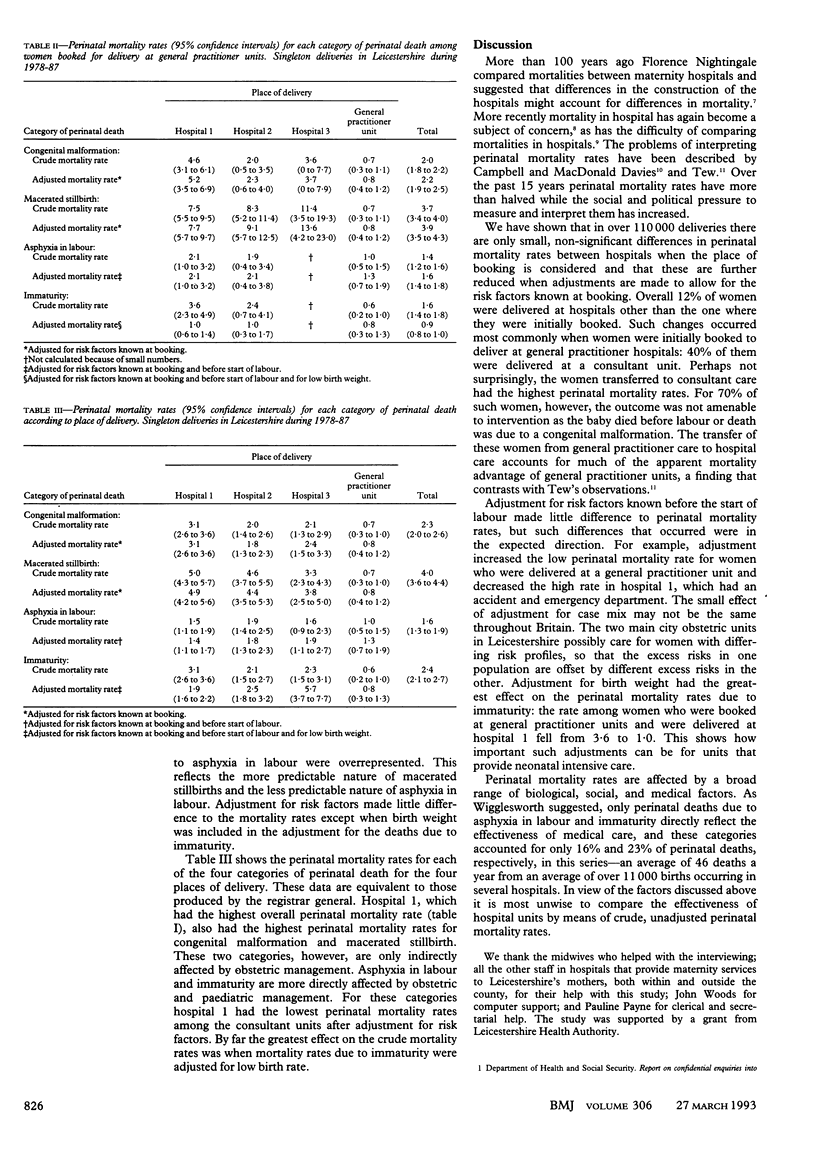

OBJECTIVE--To evaluate perinatal mortality rates as a method of auditing obstetric and neonatal care after account had been taken of transfer between hospitals during pregnancy and case mix. DESIGN--Case-control study of perinatal deaths. SETTING--Leicestershire health district. SUBJECTS--1179 singleton perinatal deaths and their selected live born controls among 114,362 singleton births to women whose place of residence was Leicestershire during 1978-87. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURE--Crude perinatal mortality rates and rates adjusted for case mix. RESULTS--An estimated 11,701 of the 28,750 women booked for delivery in general practitioner maternity units were transferred to consultant units during their pregnancy. These 11,701 women had a high perinatal mortality rate (16.8/1000 deliveries). Perinatal mortality rates by place of booking showed little difference between general practitioner units (8.8/1000) and consultant units (9.3-11.7/1000). Perinatal mortality rates by place of delivery, however, showed substantial differences between general practitioner units (3.3/1000) and consultant units (9.4-12.6/1000) because of the selective referral of high risk women from general practitioner units to consultant units. Adjustment for risk factors made little difference to the rates except when the subset of deaths due to immaturity was adjusted for birth weight. CONCLUSION--Perinatal mortality rates should be adjusted for case mix and referral patterns to get a meaningful result. Even when this is done it is difficult to compare the effectiveness of hospital units with perinatal mortality rates because of the increasingly small subset of perinatal deaths that are amenable to medical intervention.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Cain K. C., Breslow N. E. Logistic regression analysis and efficient design for two-stage studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1988 Dec;128(6):1198–1206. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R., Davies I. M., Macfarlane A., Beral V. Home births in England and Wales, 1979: perinatal mortality according to intended place of delivery. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 Sep 22;289(6447):721–724. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6447.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M., Clayton D. G., Mason E. S., MacVicar J. Asian mothers' risk factors for perinatal death--the same or different? A 10 year review of Leicestershire perinatal deaths. BMJ. 1988 Aug 6;297(6645):384–387. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6645.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink A., Yano E. M., Brook R. H. The condition of the literature on differences in hospital mortality. Med Care. 1989 Apr;27(4):315–336. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198904000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tew M. Place of birth and perinatal mortality. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1985 Aug;35(277):390–394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigglesworth J. S. Monitoring perinatal mortality. A pathophysiological approach. Lancet. 1980 Sep 27;2(8196):684–686. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92717-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]