In April 2000, the National Cancer Institute funded the Asian American Network for Cancer Awareness Research and Training (AANCART), the first Special Populations Network focused on Asian Americans on a national scale that had as its first specific aim, the building of a robust and sustainable infrastructure to increase cancer awareness, research, and training among Asian Americans in four major cities (New York, Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles). The infrastructure was established to enable attainment of its two other specific aims related to partnerships: participation of Asian Americans in clinical and prevention trials, training, and development of pilot projects; and formulating grant-funded research to reduce the burden of cancer among Asian Americans. All three of these aims have been reached.1 The objectives of this paper are to (1) describe AANCART’s transdisciplinary infrastructure; (2) document its effectiveness; and (3) delineate principles that may be transferable to other transdisciplinary approaches to health concerns.

Background

Prior to the establishment of the AANCART in April 2000 and despite documentation of cancer health disparities among Asian Americans,2–9 no National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded national infrastructure for Asians existed that was parallel to the Black Leadership Initiative on Cancer or Redes en Action (Hispanic Leadership Initiative on Cancer). In many respects, the cancer burden among Asian Americans has been overlooked. Although heart disease has been the leading cause of death for the U.S. population as a whole, few realize that cancer has been consistently the leading cause of death for Asian or Pacific Islander women ever since 1980, the first year that the Federal government used the Asian or Pacific Islander category.10 The National Center for Health Statistics reported for the year 2000 Asian or Pacific Islanders as a group to be the first racial/ethnic population to experience cancer as the leading cause of death.11 Being the only population with cancer as the leading cause of death sets Asian Americans apart from all other racial/ethnic populations. Importantly, many of the cancers of Asian Americans are preventable (e.g., tobacco-induced cancers are all preventable).

Thus, it was heartening that in December 1997, the NCI convened a meeting in Boston to discuss cancer control issues for Asian Americans that laid a foundation for action. The closest approximation to a national movement to address the cancer education needs of Asian Americans was a subsequently funded NCI program, Cancer Concerns for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, awarded to the author through the Asian American and Pacific Islander Health Promotion, Inc., for the period, 1998–2000. The program consisted of a national conference supported by the NCI and a variety of sponsors, and follow-up meetings to discuss the implementation of conference recommendations. A distinct characteristic of this conference was presentations on lessons learned from cancer control from representatives of each of the other major U.S. racial/ethnic minority populations: African Americans,12 Hispanic Americans,13 and American Indians14 with concluding keynote presentations by the Chair of the President’s Cancer Panel15 and the American Cancer Society’s first president for the 21st century.16 Two hundred forty health professionals, government officials, cancer survivors, American Cancer Society volunteers, and others, from 21 states, the District of Columbia, and 3 U.S.-associated Pacific Island jurisdictions attended. The resulting conference proceedings at the time of its publication constituted the most comprehensive and up-to-date scientific publication on the status of cancer prevention and control among Asian Americans.17

The AANCART proposal emerged from the work of many of the collaborators at the 1998 conference. The AANCART brought together investigators with portfolios of cancer control grants focused on Asian Americans as well as deeply committed Asian American community and clinical leaders, national and community-based Asian American organizations, the American Cancer Society, and federal and state health agency partners. The author was AANCART’s Principal Investigator (PI) and was a professor at The Ohio State University at the time of the initial funding. The NCI approved the transfer of the AANCART to the University of California at Davis with headquarters in Sacramento, California when the author moved to that institution.

Description of AANCART’s Infrastructure

The AANCART’s infrastructure consists of multiple transdisciplinary entities. These include entities that work seamlessly and simultaneously at both the network-wide (national) and regional levels. At the national level, the Steering Committee is transdisciplinary both in its function and in its composition, in keeping with the cooperative agreement with the NCI. The transdisciplinary nature of the network nationally serves as the model for the transdisciplinary composition of the regional AANCART communities, giving rise to results that could not otherwise be achieved.

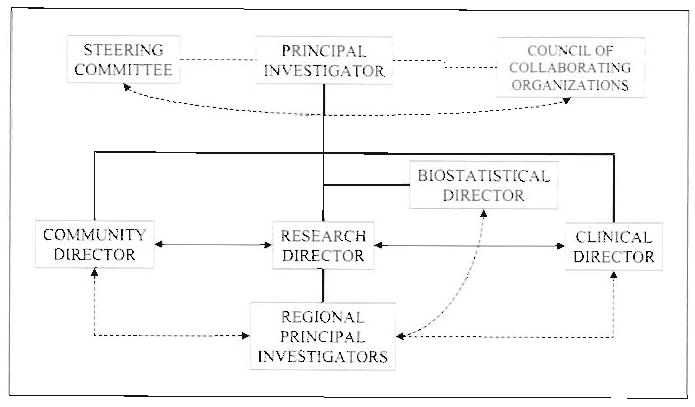

First, at the national level, the AANCART works through a 15-member, multidisciplinary, multi-ethnic Steering Committee chaired by the author and comprising the directors for biostatistics, clinical work, community work, and research; the NCI Project Officer; regional principal investigators; and others with expertise in particular Asian American cancer control issues. The Steering Committee, which is convened by the author, establishes policy, provides overall guidance and direction, serves as a communications and coordination forum throughout the AANCART, and provides support for project-related activities (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Organizational Chart for AANCART.

The transdisciplinary attributes of the Steering Committee’s composition are evident in that (1) it comprises individuals of different ethnicities and disciplines and from different institutions; (2) its members communicate regularly (despite being spread over eight cities from Honolulu to Boston), typically through monthly conference calls, electronic mail, individual telephone calls between and among members, and face-to-face meetings; and (3) the committee ensures accountability through having defined roles but working interdependently as a team. Having individuals of different ethnicities and of different disciplines (basic science, health education, medicine, psychology, and nursing) at 9 institutions (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; MD Anderson Cancer Center; San Francisco Medical Society Foundation; University of California-Davis; University of California-Los Angeles; University of California-San Francisco; University of Hawaii; and University of Washington), but all focused on cancer control for Asian Americans builds in varying points of view. Scheduled communications ensures information exchange and coordination of activities. Accountability is ensured because each member has a defined role and is accountable through a chain of command leading to the PI, who in turn is accountable to the NCI and the Steering Committee as a whole.

The Steering Committee consists of the National Directors (who oversee the arenas of research, biostatistics, clinical work, and community work) and Regional Principal Investigators (RPIs), who lead each of AANCART’s regional operations. All have equal stature but play different roles. National directors lead AANCART’s activities in the specific realms of research design (biostatistics)/research training (e.g., selection of pilot study investigators and their nurturing along with regional mentors); clinical work (e.g., building consensus among physicians on clinical guidelines for physicians who have Asian American patients); and community work (e.g., compiling and sharing cancer awareness and educational materials across the network).

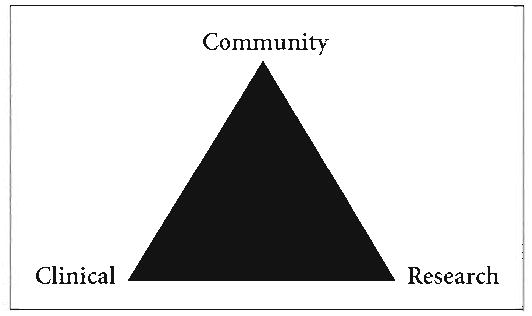

Regionally, the AANCART has a presence in New York, Houston, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Honolulu, and Sacramento. The AANCART’s regional operations are each led by an RPI and assisted by a Regional Advisory Committee analogous to the Steering Committee. The core leadership of each region is illustrated by an equilateral triangle (Figure 2), where the angles represent community, clinical, and research perspectives. No perspective is more important than any other; in particular, pilot research studies emerge because of the interactions among the three perspectives. Thus, the products that emerge (e.g., pilot research studies) may be thought of as a circle that encompasses this equilateral triangle.

Figure 2.

Typical regional infrastructure.

Documentation of Effectiveness

The AANCART’s record of accomplishments ranges from increases in cancer awareness (more than 232 cancer awareness activities fostered) to research (17 NCI-funded pilot studies funded and at least 10 other funded research grants catalyzed) to training (five National Asian American Cancer Control Academies convened with more than 600 attendees trained). The AANCART has also established a website (www.aancart.org) that serves as an electronic file cabinet of AANCART’s training materials and documents. Being competitively re-funded for 5 more years (2005 and beyond) is another sign of AANCART’s effectiveness. More details on three selected examples follow.

There are 17 NCI-funded pilot research studies that have been funded at $50,000 each for 12 months that grew out of AANCART. As a result of these studies, AANCART junior investigators have benefited from the integration of community, clinical, and research perspectives in the design and implementation of their studies. Their success is attributable to dedicated senior mentors who themselves reflect transdisciplinary perspectives in their approach to cancer control.

How the pilot study investigators were selected for submitting their pilot study proposals exemplifies the consensus approach to decision making that characterizes the AANCART’s infrastructure. The author and the AANCART Research Director established an internal review committee consisting of all of the Regional Principal Investigators (who represented different disciplines, ethnicities, and geographic regions) who in turn evaluated one-page concept papers from prospective junior investigators. This internal committee then selected the four most promising concept papers for development into full proposals. The AANCART’s leadership, especially the RPIs, nurtured the pilot study applicants. All pilot study investigators have now had a chance to present their studies at an AANCART National Cancer Control Academy and some have completed their studies.

Another sign of AANCART’s effectiveness is the development and offering of courses on basic concepts concerning cancer (referred to as Cancer 101) to lay adult audiences of Asian Americans. Initially, AANCART’s Clinical Director, Reginald Ho, MD, determined the content of these short courses, approximately 4 hours long, to be what lay adults should know about cancer. He first offered Cancer 101 to Hmong immigrants in a setting where he taught in English with an accompanying Hmong translator. This venue allowed for Hmong leaders with no English fluency to benefit from the course. Dr. Ho next offered Cancer 101 to an English-speaking Filipino audience with AANCART’s regional clinical directors and AANCART’s Community Director observing his course. Dr. Ho also engaged the audience to teach others what he taught them. Another outcome was the consensus for clinical directors and community directors to work together in offering this course. Thus, Cancer 101 has become transdisciplinary as well.

A third sign of the AANCART’s effectiveness is the development of a videotape on how a lay person should perform a fecal occult blood test for the early detection of possible colorectal cancer. No videotape, either in English or any Asian language, existed to demonstrate how individuals should perform this test, which involves not eating certain foods and collecting stool samples over a period of days. Colleagues in the AANCART developed a videotape with a Vietnamese sound track to emphasize the importance of the test and to demonstrate how to perform it. In keeping with a transdisciplinary approach, all three perspectives (clinical, community oriented, and research oriented) were involved in the creation of the videotape. Additionally, attention to cultural competence and linguistic appropriateness (e.g., correct use of Vietnamese language for a lay audience), medical accuracy were paramount in the production of this videotape.

Discussion of Implications

The vision of the AANCART is to reduce the unique, unusual, and unnecessary cancer burden being experienced by Asian Americans.18 We believe that having a transdisciplinary infrastructure as described in this paper has been fundamental to AANCART’s success. This infrastructure offers both a Network-wide and in-depth regional mechanisms to coordinate, accomplish, and communicate what no single individual or entity could do alone. The effectiveness of AANCART’s transdisciplinary infrastructure in promoting cancer awareness, research, and training for Asian Americans suggests that the principles of this transdisciplinary model should be adaptable for other diseases and other populations.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the AANCART was through a cooperative agreement (U01 CA086322) from the National Cancer Institute to the University of California, Davis on behalf of consortia partner institutions: Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Harvard University (Boston); Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Institute/University of Washington (Seattle); MD Anderson Cancer Institute/University of Texas (Houston); San Francisco Medical Society Foundation (San Francisco); University of California, Los Angeles (Los Angeles); University of California, San Francisco (San Francisco); University of Hawaii; and University of Washington.

References

- 1.Chen MS., Jr AANCART’s role in cancer awareness, research, and training. Asian Am Pacific Isl J Health. 2003 Winter-Spring;10(1):17–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin-Fu JS. Population characteristics and health care needs of Asian Pacific Islanders. Public Health Rep. 1988;103(1):18–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenkins CNH, McPhee SJ, Bird JA, Bonilla NT. Cancer risks and prevention behaviors among Vietnamese refugees. West J Med. 1990 Sep;153(3):331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen MS., Jr Behavioral and psychosocial cancer research in the underserved: an agenda for the future. Cancer. 1994 Aug 15;74(4 Suppl):1503–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940815)74:4+<1503::aid-cncr2820741616>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen MS, Jr, Hawks BL. A debunking of the myth of the healthy Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Am J Health Promot. 1995 Jul–Aug;9(6):435. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.4.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller BA, Kolonel LN, Bernstein L, et al., editors. Racial/ethnic patterns of cancer in the United States 1988–1992. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, NIH Publication No. 96–4104; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen MS., Jr Cancer prevention and control among Asian and Pacific Islander Americans: Findings and recommendations. Cancer. 1998;83(suppl 8):1856–62. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu KC. Cancer data for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Asian Am Pacific Isl J Health. 1998 Summer;6(2):130–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen MS., Jr Informal care and the empowerment of minority communities: comparisons between the U.S.A. and the United Kingdom. Ethn Health. 1999 Aug;4(3):139–51. doi: 10.1080/13557859998100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 1995. Hyattsville, MD: Public Health Service; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minino AM, Arias E, Kochanek KD, et al. Deaths: final data for 2000. National Vital Statistics Reports; 50 (15) Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones LA. Lessons learned in cancer control among African Americans. Asian Am Pacific Isl J Health. 1998 Summer–Autumn;6(2):111–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez-Stable EJ. Lessons learned from cancer prevention and control among Latinos for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Asian Am Pacific Isl J Health. 1998 Summer–Autumn;6(2):100–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burhansstipanov L. Lessons learned from Native American cancer prevention, control, and supportive care projects. Asian Am Pacific Isl J Health. 1998 Summer–Autumn;6(2):91–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freeman H. Culture, poverty, and cancer. Asian Am Pacific Isl J Health. 1998 Summer;6(2):410–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bal DG. The American Cancer Society’s Blue Ribbon Advisory Group Report on Community Cancer Control. Asian Am Pacific Isl J Health. 1998 Summer;6(2):414–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proceedings of the Cancer Concerns for Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders Conference; June 27–29, 1998; San Francisco, Calif: Published as Asian Am Pacific Isl J Health; 1998. Summer–Autumn. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen MS., Jr Cancer health disparities among Asian Americans: what we know and what we need to do. Cancer. 2005 doi: 10.1002/cncr.21501. in review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]