Background to VISION 2020 at the district level

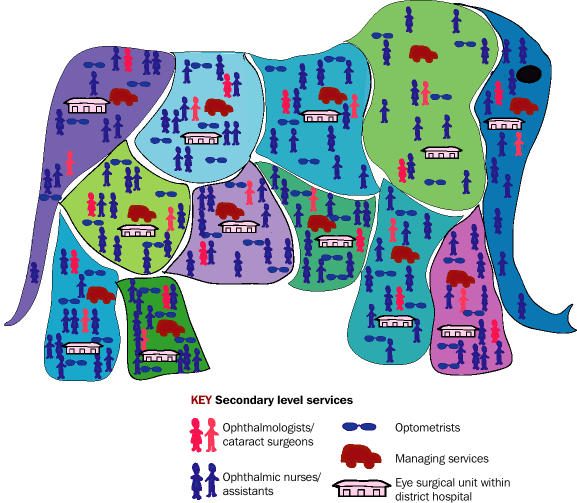

There is an African saying. The question is: “How do you eat an elephant?”. The answer is: “One mouthful at a time, slowly, with a lot of help from your friends”. There is much that we can learn from this wisdom and apply to VISION 2020. The question is: “How do you overcome the seemingly insurmountable problem of global blindness?” The answer is: “Piece by piece, in digestible portions, step by step, and working together as a team”.

Advocacy takes place globally and regionally.

Strategic planning takes place nationally.

But the actual implementation takes place at district level.

It is recommended that each of our district level VISION 2020 programmes should be for service units of about 1 million population (0.5–2 million). This administrative unit of about 1 million may be called by different names in different countries: sub-district; district; region; province etc. Whatever it is called, this service unit is what we mean when we speak of a District VISION 2020 programme. These are the ‘pieces of the elephant’. If we have a country of 40 million population, we should not plan just a single national VISION 2020 programme, but 40 separate district level VISION 2020 programmes that together make up the national programme (Figure 1).

Fig 1.

The national VISION 2020 programme should be made up of separate district level VISION 2020 programmes

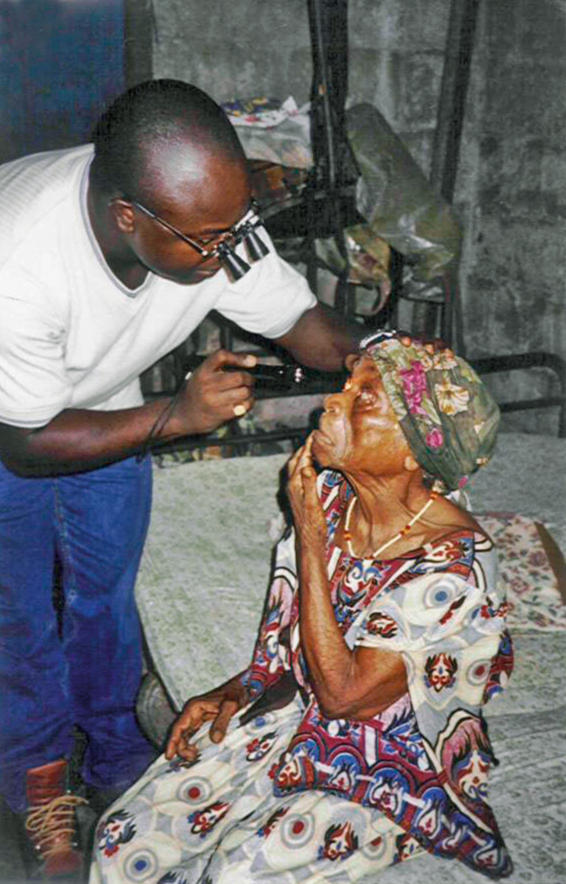

A team prepares a VISION 2020 plan. MALAWI

What is involved in VISION 2020 at the district level?

District level VISION 2020 programmes are developed as one year operational plans, prepared as integral components of the district general health operational plan, and guided by the five-year national strategic VISION 2020 plans. Each district VISION 2020 programme should, as far as possible, be horizontal, integrated into the existing district health service structure, and conforming to the principles of primary health care. These principles are equity, community involvement, focus on prevention, appropriate technology and a multi-sectoral approach. District programmes provide a continuum of comprehensive eye care, which includes eye health promotion, prevention of eye disease, curative intervention, and rehabilitation. In the past, these four elements have been working separately and without focus. With the launch of VISION 2020, the four elements have been focused and coordinated. Comprehensive eye care should be available, accessible, affordable and accountable.

Each district programme comprises a community eye care component and a surgical centre that is based in a district hospital (Figure 2). Planning and management templates for district VISION 2020 programmes are available (see list of useful resources on page 99/100). The challenge is to use these templates and adapt them for each district. All district VISION 2020 programmes will have the same elements, but no two programmes will be the same because no two districts are the same.

Fig 2.

VISION 2020 implementation

For the first phase of VISION 2020, the diseases that are prioritized are cataract and refractive error (everywhere); trachoma, vitamin A deficiency and onchocerciasis (in districts where they occur and are a public health problem). Once these diseases are being controlled, glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy are usually next in importance.

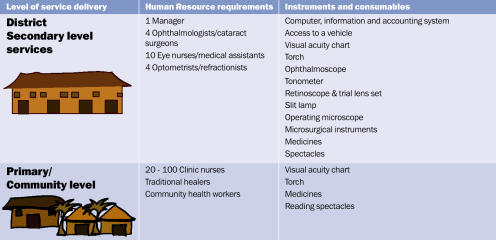

The recommended human resources for VISION 2020 at the district level specify the human resources required at community/primary clinical level and the secondary clinical level which includes management (Figure 4). These can be modified locally, according to norms and resources.

Fig 4.

Model VISION 2020 Programme (per million population)

The recommended instruments and consumables needed for VISION 2020 at the district level list requirements for the community/primary and secondary level services (Figure 4). Again, these can be modified locally.

Fig 3.

The three components of a VISION 2020 programme

The recommended service delivery model for district level VISION 2020 programmes suggests activities for cataract, refractive error, low vision, trachoma, vitamin A deficiency and onchocerciasis (Figure 5).

Fig 5.

Model VISION 2020 Programme – summary of service delivery

Partnerships for VISION 2020

We should ‘eat the elephant’ with our friends, and VISION 2020 is about partnership.

Our ministries of health signed up for VISION 2020 at the fifty-sixth World Health Assembly in 2003. They should be the primary owners of district level VISION 2020 programmes, with support from international and local non-governmental development organisation (NGDO) partners. Ideally, funding support should be provided between the partners. It is often easier for ministries of health to provide this support in the form of staff salaries or by providing the overhead running costs of the surgical centre, whilst the NGDO partners may cover the costs of supplies and consumables.

Challenges and lessons learnt from experience: The Asian context

In Pakistan, we started by piloting the concept in one district, Bannu, in the North West Frontier province. We took a department of ophthalmology at the district headquarters hospital and looked at what it had in terms of infrastructure, human resources, equipment and management.

There were two ophthalmologists, no paramedical staff, no separate operating theatre (the theatre was shared with other specialties), no separate eye ward, and minimal equipment. The output was 150 cataract operations per year.

A collaboration between the Pakistan Institute of Community Ophthalmology, the Government of North West Frontier Province and an international NGDO was established. The collaboration strengthened the district by providing equipment for the eye unit, as per the standard list approved by the National Committee for Prevention of Blindness. The government posted two new ophthalmologists trained in ECCE and IOL implantation, and five paramedics were trained, with one of the paramedics trained in management. The infrastructure was upgraded with a separate eye theatre, a separate eye ward and an outpatient complex. Primary eye care workers were trained in detection and treatment of minor disorders and referral of major ones. The eye unit was evaluated after two years, and the cataract output had increased sevenfold to 1,050 operations.

Fig 6.

Map showing Bannu district in North West Frontier Province, Pakistan

Once the cataract services were established, other services were added. The programme now includes successful refractive and low vision services, and a trachoma control programme. Eye care services for children will soon be added.

It was agreed by the National Committee that this model should be replicated in other districts in the country, with the support of INGDOs. Thus far, 53 district programmes have been established out of a total of 119 districts in Pakistan.

What have been the challenges?

One of the challenges was to build a stable and committed team. It was important to engage the government so that frequent transfers of staff would not take place. Motivation of the ophthalmologist to maintain high volume surgery is addressed by giving him/her a forum to display surgical results every year and establishing a system of peer review. Monitoring of outcomes needs to be introduced so that the ophthalmologists can maintain high standards of visual outcome (see page 100 for useful monitoring tools).

What have been the key learning points?

The service started as a cataract service and gradually grew into a comprehensive eye care service.

A primary eye care network is vital so that the unit is supported by a good referral system.

Outputs, outcomes and costs should be monitored.

Necessary measures should be adopted to ensure sustainability.

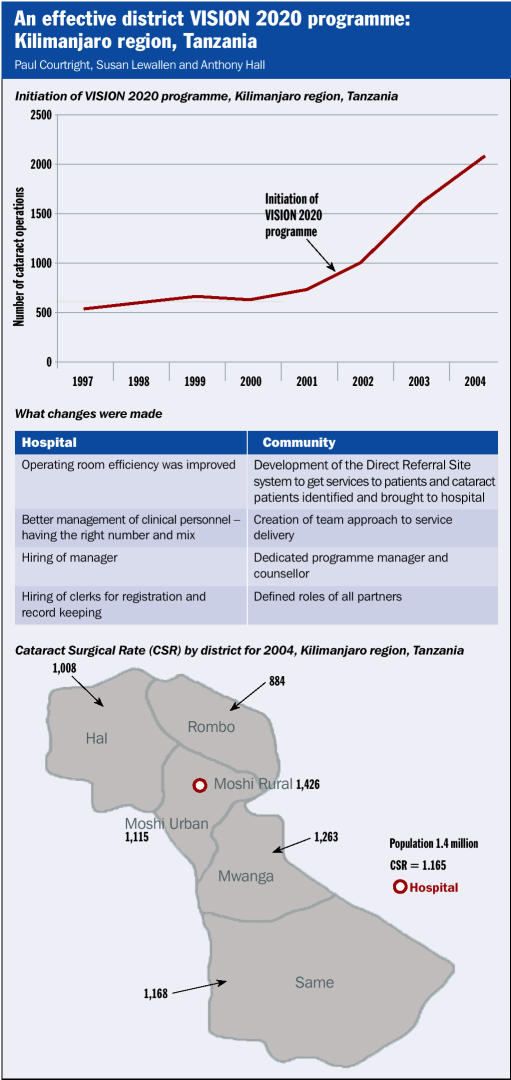

Challenges and lessons learnt from experience: The African context

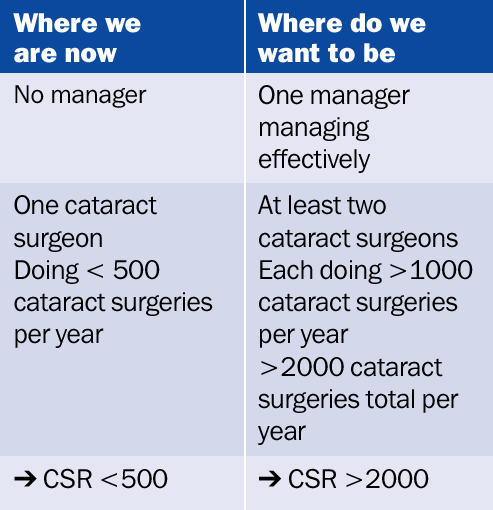

The main challenge to the successful implementation of district VISION 2020 programmes in Africa has been the lack of human resources, both clinical and managerial (Figure 6). In Africa, there is one cataract surgeon for every 1 million population. We need to double the number of cataract surgeons. Each of our cataract surgeons is presently doing less than 500 cataract surgeries per year, and this number also needs to double. This can only be achieved with effective management at the district level. There are very few district VISION 2020 programmes in Africa that have effective management. This has been the lesson we have learnt. We need to train more cataract surgeons. As importantly, we need to train effective managers. Human resource development is our priority. There are a number of success stories to illustrate the outcome of efficiently managed district programmes. The case study in the panel opposite provides an example of an effective district VISION 2020 programme in Tanzania.

Fig 6.

District VISION 2020 in Africa

Contributor Information

Colin Cook, CBM Ophthalmologist, Groote Schuur Hospital, VISION 2020 Project, Cape Town, South Africa..

Babar Qureshi, Director, Academics and Research, Pakistan Institute of Community, Ophthalmology (PICO), PO Box 125, GPO, Peshawar, Pakistan..