Abstract

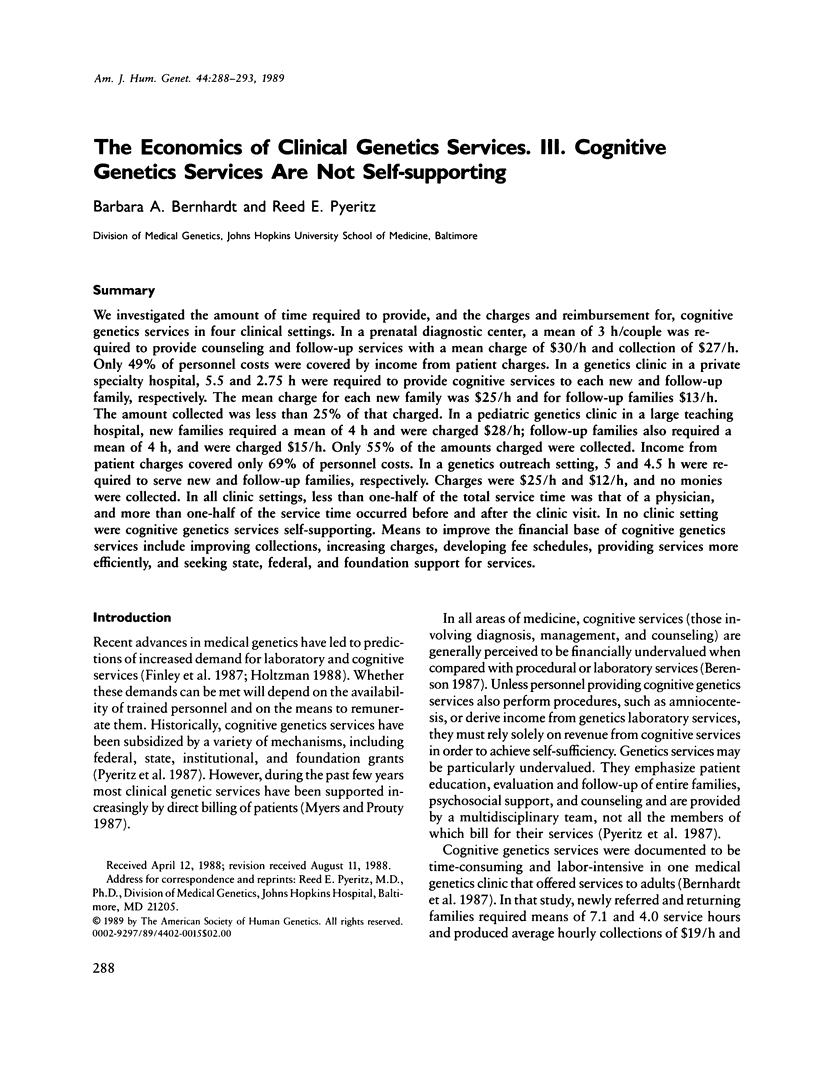

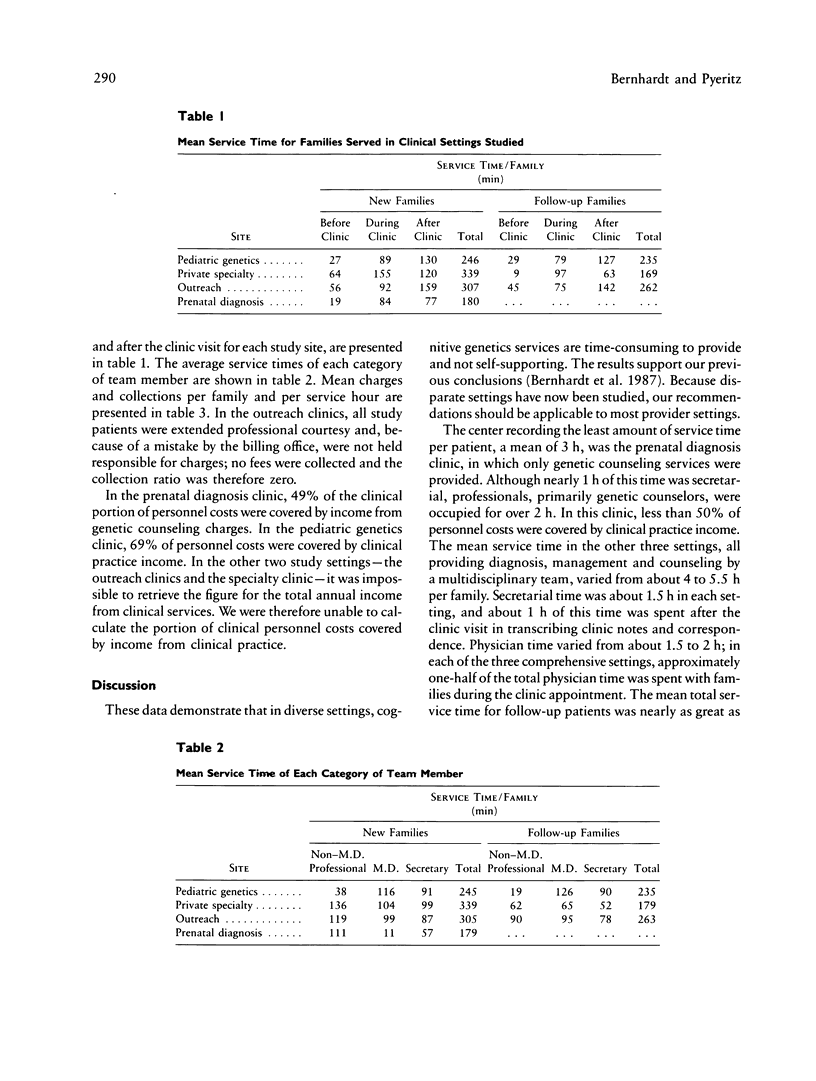

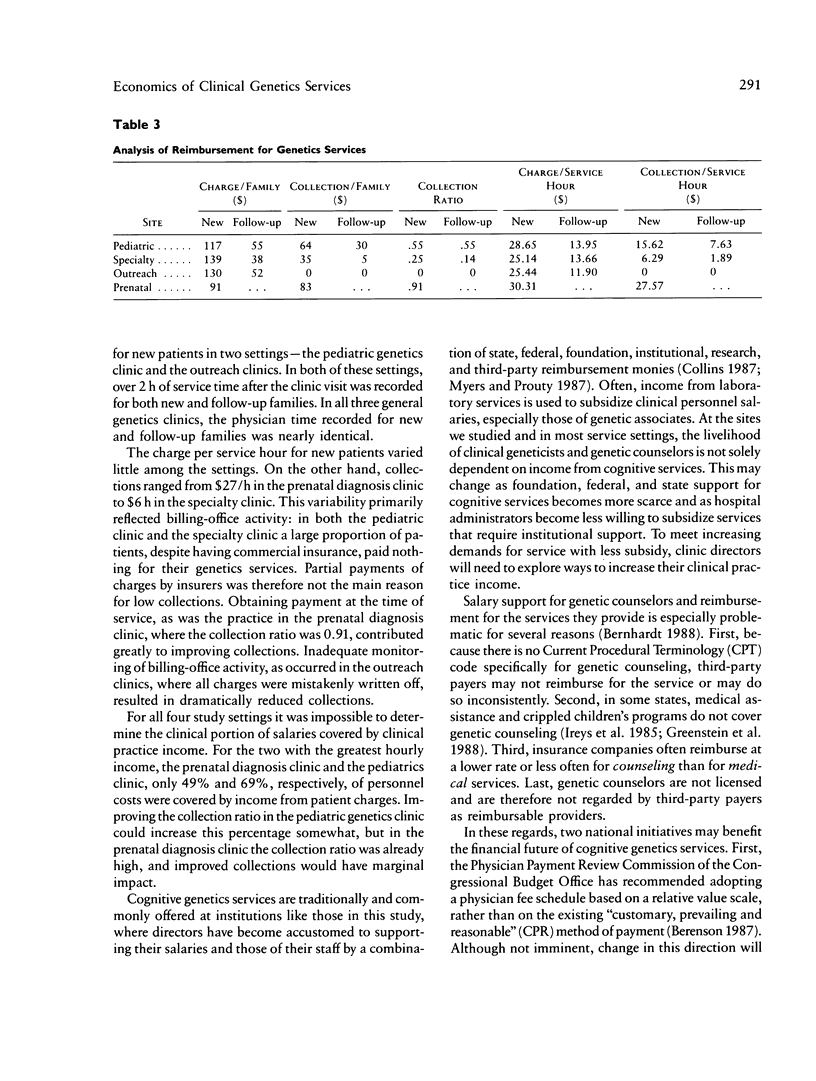

We investigated the amount of time required to provide, and the charges and reimbursement for, cognitive genetics services in four clinical settings. In a prenatal diagnostic center, a mean of 3 h/couple was required to provide counseling and follow-up services with a mean charge of $30/h and collection of $27/h. Only 49% of personnel costs were covered by income from patient charges. In a genetics clinic in a private specialty hospital, 5.5 and 2.75 h were required to provide cognitive services to each new and follow-up family, respectively. The mean charge for each new family was $25/h and for follow-up families $13/h. The amount collected was less than 25% of that charged. In a pediatric genetics clinic in a large teaching hospital, new families required a mean of 4 h and were charged $28/h; follow-up families also required a mean of 4 h, and were charged $15/h. Only 55% of the amounts charged were collected. Income from patient charges covered only 69% of personnel costs. In a genetics outreach setting, 5 and 4.5 h were required to serve new and follow-up families, respectively. Charges were $25/h and $12/h, and no monies were collected. In all clinic settings, less than one-half of the total service time was that of a physician, and more than one-half of the service time occurred before and after the clinic visit. In no clinic setting were cognitive genetics services self-supporting. Means to improve the financial base of cognitive genetics services include improving collections, increasing charges, developing fee schedules, providing services more efficiently, and seeking state, federal, and foundation support for services.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Berenson R. A. Physician payment reform: finally. Ann Intern Med. 1987 Dec;107(6):929–931. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-6-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt B. A., Weiner J., Foster E. C., Tumpson J. E., Pyeritz R. E. The economics of clinical genetics services. II. A time analysis of a medical genetics clinic. Am J Hum Genet. 1987 Oct;41(4):559–565. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley W. H., Finley S. C., Dyer R. L. Survey of medical genetics personnel. Am J Hum Genet. 1987 Apr;40(4):374–377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman N. A. Feature article: Recombinant DNA technology, genetic tests, and public policy. Am J Hum Genet. 1988 Apr;42(4):624–632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireys H. T., Hauck R. J., Perrin J. M. Variability among state Crippled Children's Service programs: pluralism thrives. Am J Public Health. 1985 Apr;75(4):375–381. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.4.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeler E. B., Solomon D. H., Beck J. C., Mendenhall R. C., Kane R. L. Effect of patient age on duration of medical encounters with physicians. Med Care. 1982 Nov;20(11):1101–1108. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198211000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers T. L., Prouty L. A. Consumer costs for genetic services. Am J Med Genet. 1987 Mar;26(3):521–530. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320260303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyeritz R. E., Tumpson J. E., Bernhardt B. A. The economics of clinical genetics services. I. Preview. Am J Hum Genet. 1987 Oct;41(4):549–558. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]