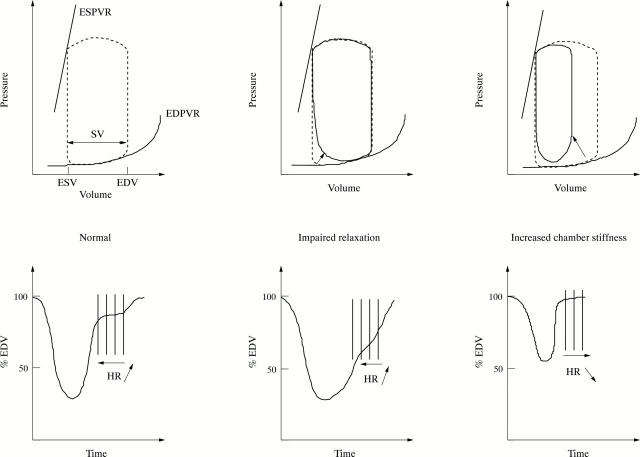

Figure 4 .

Effects of heart rate increase on left ventricular filling (the same model applies for the three parts of the figure). Top of figure: pressure−volume relation (ESV, end systolic volume; ESPVR, end systolic pressure−volume relation; EDV, end diastolic volume; EDVPR, end diastolic pressure−volume relation; SV, stroke volume). Bottom of figure: left ventricular volume changes (expressed in percentage end diastolic volume (EDV)) during one cardiac cycle. Vertical lines summarise the consequences of heart rate (HR) variations on left ventricular filling volume. Depending on the context, various increases in heart rate (leftward displacement of arrow) result in modifications of left ventricular volume filling. In normal subjects (left part of the figure) with normal pressure−volume relation (dashed line loop), modifications of heart rate mainly affect diastasis. Volume changes during this period are minor, with most of the filling occurring in early and late diastole, so that tachycardia, up to a critical limit, does not significantly affect ventricular volume. In patients with impaired relaxation (middle part of the figure), because of the delayed early diastolic rapid filling phase (solid line loop in the top of the figure), diastasis is shortened or abolished and atrial systolic filling is increased in compensation for the reduced contribution of rapid filling. So, inappropriate tachycardia will significantly reduce ventricular filling. This explains the benefit of heart rate lowering drugs in patients with impaired relaxation and heart failure caused by inappropriate tachycardia. Finally, in patients with increased chamber stiffness (right part of the figure), stroke volume is reduced (solid line loop in the top of the figure) and there is a leftward and upward displacement of the end diastolic pressure−volume relation (arrow). So, tachycardia represents a compensatory response to reduced systolic ejection volume. In these patients, a heart rate lowering drug may have a deleterious effect, by creating an important increase of pressure levels even with small volume variations, caused by the steep end diastolic pressure−volume relation.