Abstract

OBJECTIVES—To validate a simplified estimate of peak power (SPP) against true (invasively measured) peak instantaneous power (TPP), to assess the feasibility of measuring SPP during exercise and to correlate this with functional capacity. DESIGN—Development of a simplified method of measurement and observational study. SETTING—Tertiary referral centre for cardiothoracic disease. SUBJECTS—For validation of SPP with TPP, seven normal dogs and four dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy were studied. To assess feasibility and clinical significance in humans, 40 subjects were studied (26 patients; 14 normal controls). METHODS—In the animal validation study, TPP was derived from ascending aortic pressure and flow probe, and from Doppler measurements of flow. SPP, calculated using the different flow measures, was compared with peak instantaneous power under different loading conditions. For the assessment in humans, SPP was measured at rest and during maximum exercise. Peak aortic flow was measured with transthoracic continuous wave Doppler, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures were derived from brachial sphygmomanometry. The difference between exercise and rest simplified peak power (Δ SPP) was compared with maximum oxygen uptake (V̇O2max), measured from expired gas analysis. RESULTS—SPP estimates using peak flow measures correlated well with true peak instantaneous power (r = 0.89 to 0.97), despite marked changes in systemic pressure and flow induced by manipulation of loading conditions. In the human study, V̇O2max correlated with Δ SPP (r = 0.78) better than Δ ejection fraction (r = 0.18) and Δ rate-pressure product (r = 0.59). CONCLUSIONS—The simple product of mean arterial pressure and peak aortic flow (simplified peak power, SPP) correlates with peak instantaneous power over a range of loading conditions in dogs. In humans, it can be estimated during exercise echocardiography, and correlates with maximum oxygen uptake better than ejection fraction or rate-pressure product. Keywords: stress echocardiography; oxygen consumption; left ventricular function; cardiac power output

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (141.9 KB).

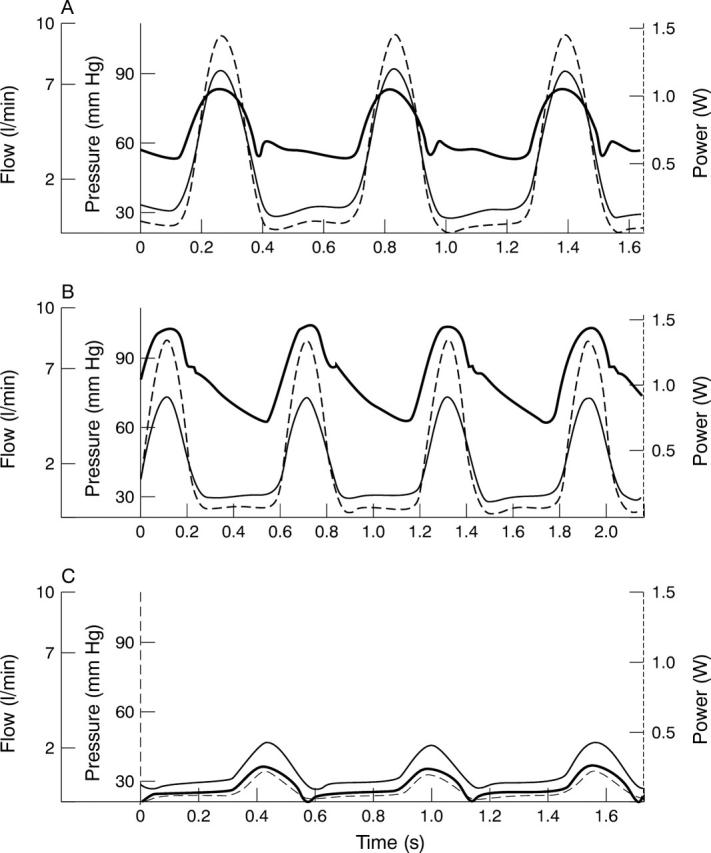

Figure 1 .

Haemodynamic alterations in the open chest canine model: screen shots from the custom analysis program showing haemodynamic responses. Flow (thin solid line) is ascending aortic flow from perivascular flow probe. Pressure (thick solid line) is ascending aortic pressure from micromanometer catheter. Power (broken line) is left ventricular power, the instantaneous product of the pressure and flow. (A) Baseline. (B) During partial aortic occlusion; pressure increases, flow falls, but power remains similar to baseline. (C) During vena cava occlusion; pressure, flow, and power all decrease dramatically. See text for further details.

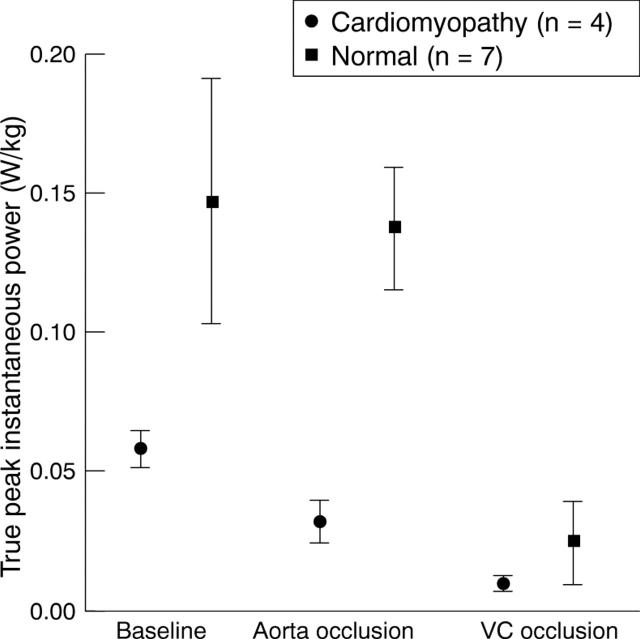

Figure 2 .

Differences in peak instantaneous power between normal and cardiomyopathic dogs. True peak instantaneous power per kg body weight for normal and cardiomyopathic dogs during different haemodynamic stages. Error bars represent SEM. VC, vena cava. Cardiomyopathic dogs have lower peak instantaneous power during baseline and aortic occlusion (p < 0.001), but not during vena cava occlusion (p = 0.09).

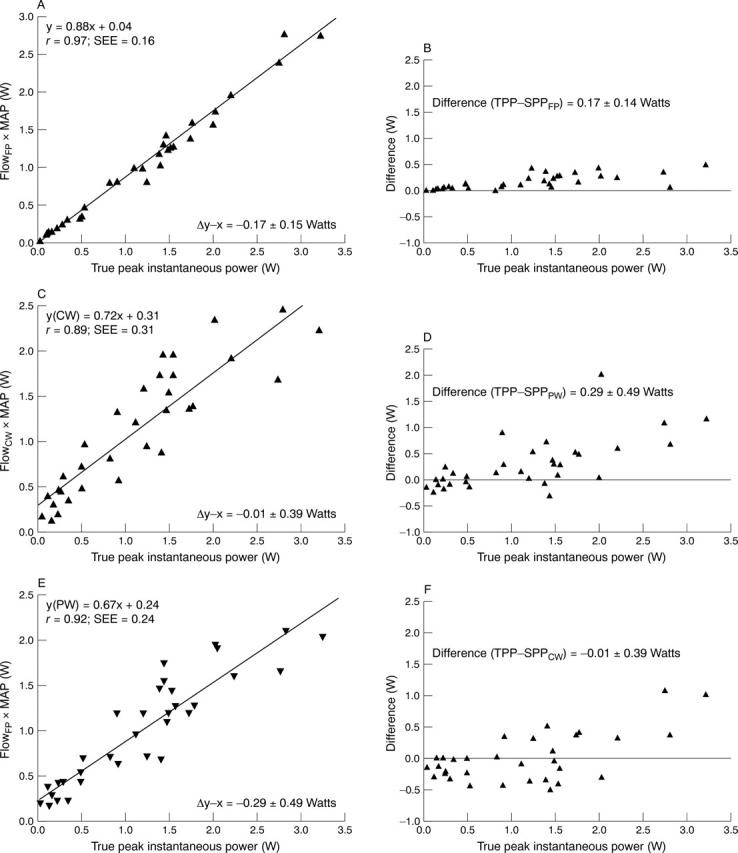

Figure 3 .

Simplified peak power estimates compared with peak instantaneous power in dogs. Simplified peak power (SPP) estimates using peak flow measured with flow probe shows excellent correlation with true peak instantaneous power (A), with minor overestimation of higher levels of power shown on the Bland-Altman plot (B). When echocardiographic estimates of flow are used to estimate simplified peak power there is some increase in scatter but still a good correlation with true peak instantaneous power, using continuous wave (CW) Doppler (C and D) and pulse wave (PW) Doppler (E and F).

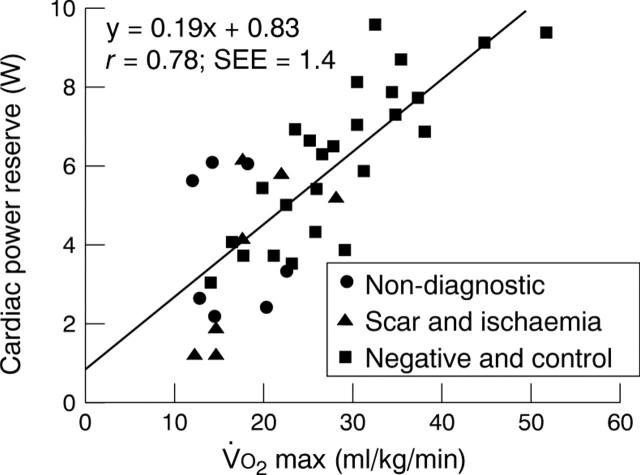

Figure 4 .

Correlation of cardiac power reserve (ΔSPP) with V̇O2max in 26 patients and 14 control subjects. Non-diagnostic, non-diagnostic exercise test because heart rate response was < 85% of maximum predicted for age. Scar and ischaemia, left ventricular wall motion abnormality by cross sectional echocardiography at rest (scar) or with exercise (ischaemia). Negative and control, exercise echocardiography in patients (negative) and normal volunteers (control) with adequate heart rate response and no wall motion abnormality at rest or on exercise.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bain R. J., Tan L. B., Murray R. G., Davies M. K., Littler W. A. The correlation of cardiac power output to exercise capacity in chronic heart failure. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1990;61(1-2):112–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00236703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum V., Carrière E. G., Kolsters W., Mosterd W. L., Schiereck P., Wesseling K. H. Aortic and peripheral blood pressure during isometric and dynamic exercise. Int J Sports Med. 1997 Jan;18(1):30–34. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-972591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borow K. M., Neumann A., Lang R. M., Ehler D., Valentine-Bates B., Wolff A., Friday K., Murphy M. Noninvasive assessment of the direct action of oral nifedipine and nicardipine on left ventricular contractile state in patients with systemic hypertension: importance of reflex sympathetic responses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993 Mar 15;21(4):939–949. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90351-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke G. A., Marshall P., al-Timman J. K., Wright D. J., Riley R., Hainsworth R., Tan L. B. Physiological cardiac reserve: development of a non-invasive method and first estimates in man. Heart. 1998 Mar;79(3):289–294. doi: 10.1136/hrt.79.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan M., Aubry N., Baleynaud S., Ferreira B., Yu J., Gourgon R. Influence of preload reserve on stroke volume response to exercise in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction: a Doppler echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Mar 1;25(3):680–686. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00449-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan M., Paillole C., Martin D., Gourgon R. Determinants of stroke volume response to exercise in patients with mitral stenosis: a Doppler echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993 Feb;21(2):384–389. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90679-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunselman P. H., Kuntze C. E., van Bruggen A., Beekhuis H., Piers B., Scaf A. H., Wesseling H., Lie K. I. Value of New York Heart Association classification, radionuclide ventriculography, and cardiopulmonary exercise tests for selection of patients for congestive heart failure studies. Am Heart J. 1988 Dec;116(6 Pt 1):1475–1482. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90731-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton G. M., Cody R. J., Binkley P. F. Increased aortic impedance precedes peripheral vasoconstriction at the early stage of ventricular failure in the paced canine model. Circulation. 1993 Dec;88(6):2714–2721. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.6.2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfine H., Aurigemma G. P., Zile M. R., Gaasch W. H. Left ventricular length-force-shortening relations before and after surgical correction of chronic mitral regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998 Jan;31(1):180–185. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00453-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. L., Pryor D. B., Pieper K. S., Harrell F. E., Jr, Califf R. M., Mark D. B., Hlatky M. A., Coleman R. E., Cobb F. R., Jones R. H. Prognostic value of radionuclide angiography in medically treated patients with coronary artery disease. A comparison with clinical and catheterization variables. Circulation. 1990 Nov;82(5):1705–1717. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.5.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung D. Y., Griffin B. P., Stewart W. J., Cosgrove D. M., 3rd, Thomas J. D., Marwick T. H. Left ventricular function after valve repair for chronic mitral regurgitation: predictive value of preoperative assessment of contractile reserve by exercise echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996 Nov 1;28(5):1198–1205. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(96)00281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini D. M., Eisen H., Kussmaul W., Mull R., Edmunds L. H., Jr, Wilson J. R. Value of peak exercise oxygen consumption for optimal timing of cardiac transplantation in ambulatory patients with heart failure. Circulation. 1991 Mar;83(3):778–786. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.3.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandarino W. A., Pinsky M. R., Gorcsan J., 3rd Assessment of left ventricular contractile state by preload-adjusted maximal power using echocardiographic automated border detection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998 Mar 15;31(4):861–868. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmor A., Raphael T., Marmor M., Blondheim D. Evaluation of contractile reserve by dobutamine echocardiography: noninvasive estimation of the severity of heart failure. Am Heart J. 1996 Dec;132(6):1195–1201. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(96)90463-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmor A., Schneeweiss A. Prognostic value of noninvasively obtained left ventricular contractile reserve in patients with severe heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997 Feb;29(2):422–428. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulinier L., Venet T., Schiller N. B., Kurtz T. W., Morris R. C., Jr, Sebastian A. Measurement of aortic blood flow by Doppler echocardiography: day to day variability in normal subjects and applicability in clinical research. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991 May;17(6):1326–1333. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada N., Chaitman B. R., Miller L. W., Yip D., Cishek M. B., Wolford T. L., Donohue T. J. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing identifies low risk patients with heart failure and severely impaired exercise capacity considered for heart transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998 Mar 1;31(3):577–582. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00533-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassi A., Jr, Crawford M. H., Richards K. L., Miller J. F. Differing mechanisms of exercise flow augmentation at the mitral and aortic valves. Circulation. 1988 Mar;77(3):543–551. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooke G. A., Feigl E. O. Work as a correlate of canine left ventricular oxygen consumption, and the problem of catecholamine oxygen wasting. Circ Res. 1982 Feb;50(2):273–286. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell L. B., Brengelmann G. L., Blackmon J. R., Bruce R. A., Murray J. A. Disparities between aortic and peripheral pulse pressures induced by upright exercise and vasomotor changes in man. Circulation. 1968 Jun;37(6):954–964. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.37.6.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller N. B., Shah P. M., Crawford M., DeMaria A., Devereux R., Feigenbaum H., Gutgesell H., Reichek N., Sahn D., Schnittger I. Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two-dimensional echocardiography. American Society of Echocardiography Committee on Standards, Subcommittee on Quantitation of Two-Dimensional Echocardiograms. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1989 Sep-Oct;2(5):358–367. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(89)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seed W. A., Wood N. B. Velocity patterns in the aorta. Cardiovasc Res. 1971 Jul;5(3):319–330. doi: 10.1093/cvr/5.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharir T., Feldman M. D., Haber H., Feldman A. M., Marmor A., Becker L. C., Kass D. A. Ventricular systolic assessment in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy by preload-adjusted maximal power. Validation and noninvasive application. Circulation. 1994 May;89(5):2045–2053. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharir T., Marmor A., Ting C. T., Chen J. W., Liu C. P., Chang M. S., Yin F. C., Kass D. A. Validation of a method for noninvasive measurement of central arterial pressure. Hypertension. 1993 Jan;21(1):74–82. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H., Schiller N. B. Progress in developing a noninvasive load-independent marker of ventricular contractility. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998 Mar 15;31(4):869–870. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelken A. M., Younis L. T., Jennison S. H., Miller D. D., Miller L. W., Shaw L. J., Kargl D., Chaitman B. R. Prognostic value of cardiopulmonary exercise testing using percent achieved of predicted peak oxygen uptake for patients with ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996 Feb;27(2):345–352. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00464-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringer W. W., Hansen J. E., Wasserman K. Cardiac output estimated noninvasively from oxygen uptake during exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1997 Mar;82(3):908–912. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.3.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L. B., Bain R. J., Littler W. A. Assessing cardiac pumping capability by exercise testing and inotropic stimulation. Br Heart J. 1989 Jul;62(1):20–25. doi: 10.1136/hrt.62.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L. B. Cardiac pumping capability and prognosis in heart failure. Lancet. 1986 Dec 13;2(8520):1360–1363. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L. B. Clinical and research implications of new concepts in the assessment of cardiac pumping performance in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1987 Aug;21(8):615–622. doi: 10.1093/cvr/21.8.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L. B. Evaluation of cardiac dysfunction, cardiac reserve and inotropic response. Postgrad Med J. 1991;67 (Suppl 1):S10–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L. B., Littler W. A. Measurement of cardiac reserve in cardiogenic shock: implications for prognosis and management. Br Heart J. 1990 Aug;64(2):121–128. doi: 10.1136/hrt.64.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thadani U., Parker J. O. Hemodynamics at rest and during supine and sitting bicycle exercise in normal subjects. Am J Cardiol. 1978 Jan;41(1):52–59. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(78)90131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. D. Flow in the descending aorta. A turn of the screw or a sideways glance? Circulation. 1990 Dec;82(6):2263–2265. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.6.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Broek S. A., van Veldhuisen D. J., de Graeff P. A., Landsman M. L., Hillege H., Lie K. I. Comparison between New York Heart Association classification and peak oxygen consumption in the assessment of functional status and prognosis in patients with mild to moderate chronic congestive heart failure secondary to either ischemic or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1992 Aug 1;70(3):359–363. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90619-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]