Abstract

Aims: To study the expression of Ki-67 and cytokeratin 20 (CK20) in a group of hyperplastic polyps (including a group with “atypical” features) with the aim of determining whether upper crypt Ki-67 staining and lower crypt CK20 staining correlated with these atypical features, as assessed by light microscopy.

Methods: Fifty seven formalin fixed, paraffin wax embedded hyperplastic colorectal polyps from 53 patients were selected on histological grounds; these comprised 26 typical polyps and 31 with atypical features, which included nuclear hyperchromatism, basal crowding, and increased mitotic activity. These polyps were examined using a standard immunohistochemical method with antibodies against CK20 and Ki-67. Comparisons were made with normal mucosa, adenomatous polyps, and carcinomas.

Results: Of the 26 typical polyps, 17 showed the usual pattern of lower crypt Ki-67 and upper crypt CK20 staining; one with upper crypt Ki-67 staining but normal surface CK20 staining; seven with Ki-67 confined to the lower half of crypts but with scattered lower crypt CK20; and one with both upper crypt Ki-67 staining, together with scattered CK20 basal staining. Of the 31 polyps with atypical features, 11 showed the usual staining pattern of lower crypt Ki-67 staining and surface staining with CK20; two showed Ki-67 staining extending into the upper half of crypts, but with a normal surface staining with CK20; 14 showed Ki-67 confined to the lower half of crypts, but scattered lower crypt staining with CK20; and four showed upper crypt Ki-67 staining together with scattered CK20 lower crypt staining.

Conclusions: The normal pattern of lower crypt Ki-67 and upper crypt CK20 was seen in 28 of the 57 hyperplastic polyps and, in general, this corresponded with standard light microscopic appearances. Twenty one of the 57 polyps showed lower crypt mosaic CK20 staining, which in general corresponded with basal abnormalities on light microscopy, although seven specimens had normal appearances. Two smaller subsets emerged, one showing upper crypt Ki-67 staining in the presence of normal CK20 expression (three cases) and another in which a combination of lower crypt CK20 and upper crypt Ki-67 expression was seen (five cases). This last pattern was similar to that of neoplastic polyps and raises the possibility that a subgroup of hyperplastic polyps exists that may be a variant with malignant potential. Further studies with markers of mismatch repair genes and K-ras mutations may help to clarify this issue.

Keywords: hyperplastic polyps, colorectum, cytokeratin, Ki-67, immunohistochemistry

Hyperplastic polyps are common lesions and occur most frequently in the recto-sigmoid area.1 They are diagnosed on the basis of a characteristic serrated epithelial pattern, which results from micropapillary luminal infolding of columnar absorptive cells and mature goblet cells.2 Historically, their lack of dysplasia/carcinoma associated nuclear and architectural features has placed them in a benign and non-neoplastic category. However, more recent studies have demonstrated clonal relations between hyperplastic polyps and dysplastic epithelium in some mixed polyps,3 and a frequency of K-ras mutation similar to that of adenoma.4 In 1990, Longacre and Fenoglio-Preiser described mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps of the colorectum and coined the term “serrated adenoma”.5 The distinction between a serrated adenoma and a hyperplastic polyp is not always straightforward. Ajioka et al used the term “atypical hyperplastic polyp” for those polyps with some features of a serrated adenoma but where there was definite surface maturation.6 Other authors have been less precise in their use of the criteria of Longacre and Fenoglio-Preiser5 in differentiating hyperplastic polyps from serrated adenomas.7 Ban8 examined two colonic polyps that appeared to be “atypical” on light microscopy. Using the proliferative marker Ki-67 and CK20 as a marker of enterocyte maturity, he found that both polyps showed Ki-67 positive cells extending to the upper portion of some crypts and CK20 positive cells distributed in a scattered fashion. All of the “traditional” hyperplastic polyps showed Ki-67 confined to the lower half of the crypts and CK20 expression confined to the upper three quarters of the epithelium.

“More recent studies have demonstrated clonal relations between hyperplastic polyps and dysplastic epithelium in some mixed polyps, and a frequency of K-ras mutation similar to that of adenoma”

The aim of our study was to look at the expression of the same markers (Ki-67 and CK20) in a larger group of hyperplastic polyps (including a group with “atypical” features) to determine whether upper crypt Ki-67 staining and basal crypt CK20 staining correlated with these atypical features, as assessed by light microscopy.

METHODS

Fifty seven polyps of the hyperplastic type were retrieved from the files of the histopathology departments of Manchester Royal Infirmary and Stepping Hill Hospital, UK, and stained with antibodies to Ki-67 and CK20, following detailed histological review of haematoxylin and eosin stained sections. For comparison, nine moderately dysplastic (non-serrated) adenomas and seven moderately differentiated colorectal carcinomas were stained with the same antibodies.

A standard immunohistochemical method was applied for the antibodies to Ki-67 (Dako, Ely, Cambridgeshire, UK; primary antibody, 1/100 dilution; 30 minutes' incubation at room temperature after heat mediated antigen retrieval) and CK20 (Dako; primary antibody, 1/100 dilution; 30 minutes' incubation at room temperature after heat mediated antigen retrieval). Detection was with a labelled streptavidin–biotin method (Dako).

The slides were assessed independently by two observers (CRH and RFTMcM) with a κ value of 0.68. Consensus was reached after discussion. When assessing staining, Ki-67 positivity of more than very occasional cells within the upper half of crypts was considered abnormal and CK20 positivity in a scattered pattern seen within the lower crypt half was considered abnormal.

RESULTS

The 57 hyperplastic polyps (fig 1A), including 31 with atypical features (fig 1B), were from a total of 53 patients (28 men and 25 women), with an age range of 28–82 years (mean, 52.5), and were derived only from the left side of the colon. They had been fixed in 10% buffered formalin, routinely processed, and embedded in paraffin wax. Most of the polyps were received in a fragmented state. On histological measurement they ranged up to 9 mm in diameter but most were less than 5 mm. Coincidental conditions documented on the histology request cards included hereditary non-polyposis colonic carcinoma (HNPCC) in three patients, previous colorectal carcinoma (one patient), synchronous but separate colorectal carcinoma (two patients), BRCA1 gene carrier (one patient), strong family history of colorectal carcinoma (one patient), synchronous hyperplastic polyps (five patients), and synchronous neoplastic polyp (three patients). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use was not documented.

Figure 1.

(A) Low power view of typical hyperplastic polyp. (B) High power view of atypical hyperplastic polyp showing increased mitotic activity, pseudostratification, hyperchromatism, increased apoptotic cells, and an inflammatory infiltrate. (C) Glands at the base of crypts showing multinucleated epithelial cells. Haematoxylin and eosin stained.

The polyps (31 in number) categorised as atypical on light microscopy showed increased mitotic figures, pseudostratification with gland crowding, hyperchromasia, and increased apoptosis (fig 1B). Occasional multinucleated cells were seen at crypt bases in five of the 57 cases (fig 1C). In all the polyps there was definite surface maturation and the atypical features were predominantly seen in the lower and middle crypt zones; therefore, they were not felt to represent serrated adenomas. Neither did the features represent a collision between adenomatous and hyperplastic areas.

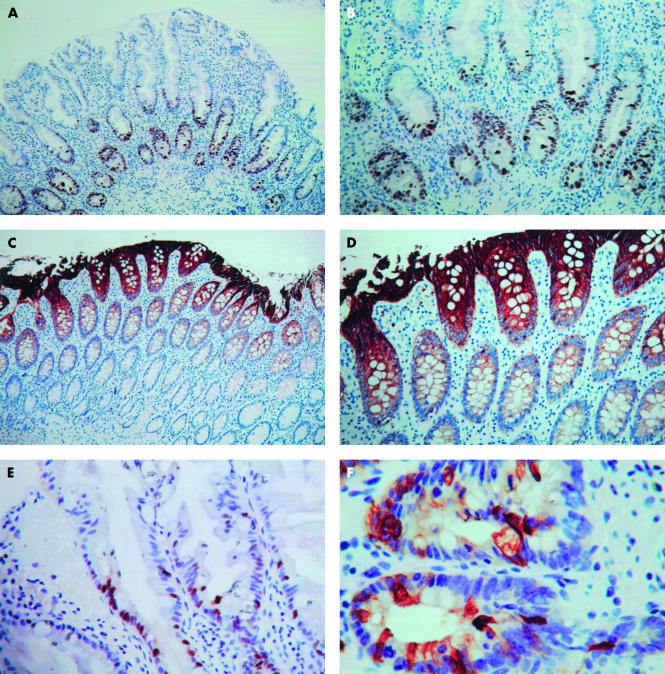

Of the 31 hyperplastic polyps with atypical features determined by light microscopy, 11 showed the usual pattern of lower crypt Ki-67 staining (fig 2A,B) and upper crypt staining with anti-CK20 (fig 2C,D); two showed Ki-67 staining extending into the upper half of the crypts (fig 2E), but with normal surface staining with anti-CK20; 14 showed Ki-67 staining confined to the lower half of the crypts but scattered lower crypt staining for CK20 (fig 2F), whereas four showed both upper crypt Ki-67 staining and scattered CK20 lower crypt staining.

Figure 2.

(A) Low power view of typical hyperplastic polyp showing lower crypt pattern of nuclear staining (Ki-67 immunostaining). (B) Higher power view demonstrating basal location (Ki-67 immunostaining). (C) Low power view of typical polyp showing upper crypt staining (cytokeratin 20 (CK20) immunostaining). (D) Higher power view showing upper crypt staining, with membranous and cytoplasmic staining (CK20 immunostaining). (E) Atypical hyperplastic polyp demonstrating upper crypt Ki-67 nuclear staining in serrated epithelium (Ki-67 immunostaining). (F) Lower crypt staining in atypical hyperplastic polyp (muscularis mucosae to right) with typical mosaic pattern (CK20 immunostaining).

Of the 26 hyperplastic polyps that appeared normal by light microscopy there were 17 with usual staining for both Ki-67 and CK20, one with upper crypt Ki-67 staining but normal surface CK20 staining, seven with Ki-67 confined to the lower half of crypts but with scattered lower crypt CK20 staining, and one with both upper crypt Ki-67 staining and scattered CK20 lower crypt staining. Table 1 summarises the results. When Fisher's exact test was applied, there was a significant difference (p = 0.036) between typical and atypical hyperplastic polyps with CK20 immunoreactivity but no significant difference (p = 0.19) for Ki-67 immunostaining.

Table 1.

Comparison of Ki-67 and cytokeratin 20 (CK20) staining in atypical and typical hyperplastic polyps

| Staining pattern | Typical on light microspopy (n=26) | Atypical on light microspopy (n=31) |

| Usual pattern (Ki-67 positivity confined to lower crypt, CK positivity confined to upper crypt) | 17 | 11 |

| Upper crypt zone Ki-67 positivity, usual pattern CK20 positivity | 1 | 2 |

| Usual pattern Ki-67 positivity with basal CK20 positivity | 7 | 14 |

| Upper crypt zone Ki-67 positivity and basal CK20 positivity | 1 | 4 |

| p=0.036 for CK20 differences (Fisher's exact test; p value for the same or stronger association); p=0.19 for Ki-67 differences (Fisher's exact test; p value for the same or stronger association). | ||

There was no apparent link between the documented coincidental conditions (HNPCC, previous colorectal carcinoma, synchronous carcinoma, BRCA1 carrier, strong family history of colorectal carcinoma, synchronous hyperplastic polyps, and synchronous neoplastic polyp) and the atypical hyperplastic polyps.

The adenomas examined showed surface staining with anti-Ki-67 and total crypt staining with anti-CK20, whereas the carcinomas showed upper crypt staining with anti-Ki-67 and total thickness staining with anti-CK20.

DISCUSSION

Colonic polyps containing simultaneous but separate areas of hyperplastic and adenomatous glands are known to exist, but in 1984 Urbanski et al reported a different type of polyp with the combined morphological features of hyperplastic and adenomatous epithelium.9 This was designated a “mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyp”. Descriptions of this phenomenon were scarce until Longacre and Fenoglio-Preiser's landmark paper on the subject was published in 1990.5 In this, they commented on 110 mixed hyperplastic/adenomatous polyps (exhibiting the architectural but not the typical bland cytological features of a hyperplastic polyp) and proposed the replacement term “serrated adenoma”.

According to Longacre and Fenoglio-Preiser,5 serrated adenomas were distinguished by several features, namely: the presence of a serrated epithelial surface in addition to goblet cell immaturity, upper crypt mitoses, prominence of nucleoli, absence of a thickened collagen table, and a nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio lying between that of hyperplastic polyps and traditional adenomas.

“Our examination of 31 hyperplastic polyps with atypical features on light microscopy revealed a difference in CK20 staining compared with that seen in the group of traditional looking hyperplastic polyps”

To overcome the difficulty of not always being able to distinguish serrated adenomas from hyperplastic polyps, Ajioka et al referred to a group of polyps as atypical hyperplastic polyps.6 These were histologically characterised by “branched serrated glands with loss of goblet cells and the presence of numerous dystrophic goblet cells, oval to spindle shaped nuclei with slight pseudostratification, and a small degree of surface maturation”. They went on to state that: “they could not be judged as serrated adenomas because of incomplete but definite surface maturation”.

Ban8 demonstrated unusual Ki-67 and CK20 staining of two hyperplastic polyps with atypical features. Both polyps appeared atypical on light microscopy, although one appeared more like a traditional hyperplastic polyp and one more like a serrated adenoma. Using the proliferative marker Ki-67 and CK20 as a marker of enterocyte maturity, he found that both polyps showed Ki-67 positive cells extending to the upper portion of some crypts and CK20 positive cells distributed in a scattered fashion. He compared this staining with that seen in traditional looking hyperplastic polyps and tubular adenomas. All of the traditional hyperplastic polyps showed Ki-67 confined to the lower half of crypts and CK20 expression confined to the upper three quarters of the epithelium, whereas in the tubular adenomas Ki-67 was in the upper half of the crypts and CK20 staining was relatively weak and showed a scattered distribution.

Our examination of 31 hyperplastic polyps with atypical features on light microscopy revealed a difference in CK20 staining compared with that seen in the group of traditional looking hyperplastic polyps. The normal pattern of basal Ki-67 and upper crypt CK20 expression was seen in nearly half of our hyperplastic polyps and, in general, these corresponded with standard light microscopic appearances, although some showed basal abnormalities, focally associated with inflammation. Approximately two fifths showed lower crypt mosaic CK20 staining, which in general corresponded with basal abnormalities on light microscopy, although seven cases had normal appearances. Two smaller subsets emerged, one demonstrating upper crypt Ki-67 staining in the presence of normal CK20 expression (five cases) and another in which a combination of lower crypt CK20 and upper crypt Ki-67 expression was seen (three cases). This pattern was similar to that of neoplastic polyps, although on light microscopic examination there was no suggestion that these were adenomas of either usual or serrated type according to the criteria of Longacre and Fenoglio–Preiser.5 No obvious correlation with coincidental clinical conditions was seen in either of these subsets.

Recent reports have stressed the importance of right sided colonic hyperplastic/serrated polyps in the development of colonic carcinomas with microsatellite instability (MSI).10 However, our study was confined to the patterns of expression of CK20 and Ki-67 in left sided polyps only. In our population group, right sided polyps are unusual and insufficient numbers were available for review. This is a potential area for future research.

These are preliminary data but raise the possibility that some hyperplastic polyps, particularly those with atypical lower crypt features on light microscopy, may represent a variant with neoplastic potential. CK20 is, among other things, a marker of enterocyte maturity11 and the relevance of this aberrant staining in the lower crypt cells is uncertain. However, this disordered maturation may be another step away from the long assumed benign nature of these colonic lesions, and again raises the question as to whether the hyperplastic polyp should be considered part of a “neoplastic continuum” including serrated adenomas.12

Take home messages.

The normal pattern of lower crypt Ki-67 and upper crypt cytokeratin 20 (CK20) staining was seen in 28 of the 57 hyperplastic polyps and, in general, this corresponded with standard light microscopic appearances

Twenty one of the 57 polyps showed lower crypt mosaic CK20 staining, which in general corresponded with basal abnormalities on light microscopy, although seven specimens had normal appearances

Two smaller subsets emerged, one showing upper crypt Ki-67 staining in the presence of normal CK20 expression (three cases) and another in which a combination of lower crypt CK20 and upper crypt Ki-67 was seen (five cases)

This last pattern was similar to that of neoplastic polyps and raises the possibility that a subgroup of hyperplastic polyps exists that may be a variant with malignant potential

Further studies with markers of mismatch repair genes and K-ras mutations are needed to help clarify this issue

Further work is necessary, particularly with reference to the previously described variations in K-ras mutations,4 loss of O6-methyl guanine-DNA methyl transferase (MGMT) expression,12,13 expression of mismatch repair genes, and MSI.14 These may help to clarify the current situation, which is that “the nature of hyperplastic polyps remains unclear”.15

Abbreviations

CK, cytokeratin

HNPCC, hereditary non-polyposis colonic carcinoma

MSI, microsatellite instability

REFERENCES

- 1.Franzin G, Dina R, Zamboni G, et al. Hyperplastic (metaplastic) polyps of the colon. A histologic and histochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol 1984;8:687–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang M, Mitomi H, Sada M, et al. Ki-67, p53, and Bcl-2 expression of serrated adenomas of the colon. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iino H, Jass JR, Simms LA, et al. DNA microsatellite instability in hyperplastic polyps, serrated adenomas, and mixed polyps: a mild mutator pathway for colorectal cancer? J Clin Pathol 1999;52:5–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otori K, Oda Y, Sugiyama K, et al. High frequency of K-ras mutations in human colorectal hyperplastic polyps. Gut 1997;40:660–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longacre TA, Fenoglio-Preiser CM. Mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps/serrated adenomas. Am J Surg Pathol 1990;14:524–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ajioka Y, Watanabe H, Jass JR, et al. Infrequent K-ras codon 12 mutation in serrated adenomas of human colorectum. Gut 1998;42:680–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makinen MJ, George SMC, Jernvall P, et al. Colorectal carcinoma associated with serrated adenoma—prevalence, histological features and prognosis. J Pathol 2001;193:286–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ban S. Small hyperplastic polyps of the colorectum showing deranged cell organization: a lesion considered to be a serrated adenoma [letter]? Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:1158–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urbanski SJ, Kossakowska AE, Marcon N, et al. Mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps—an underdiagnosed entity. Am J Surg Pathol 1984;8:551–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawkins NJ, Ward RL. Sporadic colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability and their possible origin in hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:1307–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moll R, Lowe A, Laufer J, et al. Cytokeratin 20 in human carcinomas. A new histodiagnostic marker detected by monoclonal antibodies. Am J Pathol 1992;140:427–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jass J. Serrated route to colorectal cancer: back street or super highway? J Pathol 2001;193:283–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitehall VLJ, Walsh MD, Young J, et al. Methylation of O-6 methylguanine DNA methyltransferase characterises a subset of colorectal cancer with low-level DNA microsatellite instability. Cancer Res 2001;61:827–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jass JR, Young J, Leggett BA. Hyperplastic polyps and DNA microsatellite unstable cancers of the colorectum. Histopathology 2000;37:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jass JR, Iino H, Ruszkiewicz A, et al. Neoplastic progression occurs through mutator pathways in hyperplastic polyposis of the colorectum. Gut 2000;47:43–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]