Churg‐Strauss Syndrome (CSS) is a small vessel systemic vasculitis, characterised by asthma, peripheral eosinophilia, neuropathy, pulmonary infiltrates, and sinus abnormalities.1 Conventional treatment with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide2 controls disease activity; however, relapse is frequent and the treatment is toxic. Alternative treatments include plasma exchange,3 interferon alfa,4 and intravenous immunoglobulin.5 B cell depletion with rituximab has proved effective in autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis.6 We present two cases of patients with refractory CSS who were successfully treated with rituximab.

A 37 year old woman (case 1) presented with an 8 month history of nasal congestion, hearing loss, lymphadenopathy, rash, breast inflammation, peripheral neuropathy, abdominal pain, malaise, and weight loss. Tachydysrhythmias with poor left ventricular function on echocardiogram suggested cardiac vasculitis. Bone marrow nasal and skin biopsies demonstrated prominent eosinophil infiltration, and a chest computed tomography scan showed pulmonary infiltrates. There was a peripheral eosinophilia (7.4×109/l), and raised C reactive protein 48 mg/l; ANCA were negative. CSS was diagnosed.

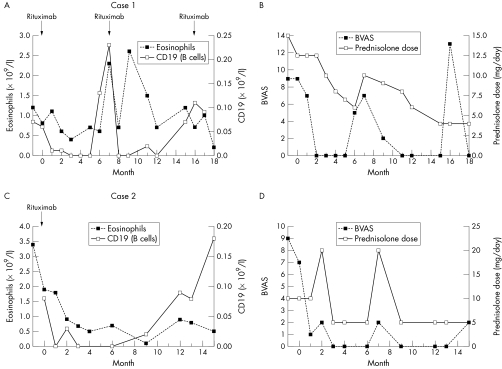

Initial treatment with intravenous (IV) cyclophosphamide and oral prednisolone induced temporary remission, but subsequent relapses were treated with IV methylprednisolone, high dose pooled IV immunoglobulin, mycophenolate mofetil, and alemtuzumab, (Campath‐1H, anti‐52 monoclonal antibody). Five months after a third course of alemtuzumab her disease relapsed, presenting with malaise, nasal obstruction, asthma, and peripheral neuropathy. She received treatment with rituximab (as four, weekly, doses of 375 mg/m2). The patient received further rituximab at 7 and 16 months in response to a return of eosinophilia, nasal symptoms, and asthma after B cell reconstitution (figs 1A and B).

Figure 1 Case 1: (A) sequential eosinophil and CD19 counts and (B) Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS) and prednisolone dose after rituximab administration. Case 2: (C) sequential eosinophil and CD19 counts and (D) BVAS and prednisolone dose after rituximab administration.

A 35 year old woman (case 2) with known CSS presented in January 2004 with relapsing disease reflected by malaise, fatigue, asthma, peripheral neuropathy, night sweats, polyarthritis, multiple subcutaneous nodules, and an erythematous rash. The original presentation at the age of 21 was additionally characterised by respiratory failure and gastrointestinal involvement. Previous treatment included cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil interferon alfa, and alemtuzumab. Repeat skin biopsy confirmed granulomatous infiltrates with necrotising foci and eosinophils. She failed to respond to further alemtuzumab and developed deteriorating respiratory symptoms, nasal congestion, and breast inflammation.

Rituximab was given as two infusions of 1000 mg 2 weeks apart. During the follow up period, the patient had two respiratory tract infections, which were treated with temporary increases in prednisolone dose and oral antibiotics. B cell counts recovered 9 months after rituximab without reappearance of an eosinophilia or disease relapse (figs 1C and D).

The diagnoses of CSS were based on disease manifestations and biopsy findings, which disclosed eosinophil infiltrates according to the criteria of the American College of Rheumatology1 and the Chapel Hill consensus disease definitions. Corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide were initially effective in controlling disease activity. Both our patients had long histories of relapsing disease activity, despite continuous immune suppressive treatment and alternative immunotherapies.

In CSS, eosinophil activation is mainly responsible for disease manifestations, and cytokines produced by T lymphocytes, such as interleukin (IL) 4, IL5,7 and IL13,8 are increased in active CSS. This suggests that hypereosinophilia is secondary to T cell involvement in the disease pathogenesis. T cell autoreactivity has been shown to be B cell dependent in certain experimental models,9,10 and this dependency has been proposed to explain the therapeutic response to rituximab in human autoimmunity. We therefore suggest a hierarchy of dysregulation in CSS, linking B cells with the eosinophilia through autoreactive T cells.

Rituximab was successful in controlling disease activity both on initial presentation and during a flare in our patients. B cell depletion was achieved and the eosinophil count decreased to normal levels. B cell depletion may be an alternative treatment for other patients with refractory CSS.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the assistance of Stella Burns, research sister, in the supervision of rituximab treatment and subsequent patient care.

References

- 1.Masi A T, Hunder G G, Lie J T, Michel B A, Bloch D A, Arend W P.et al The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Churg‐Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and angiitis). Arthritis Rheum 1990331094–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gayraud M, Guillevin L, Cohen P, Lhote F, Cacoub P, Deblois P.et al Treatment of good‐prognosis polyarteritis nodosa and Churg‐Strauss syndrome: comparison of steroids and oral or pulse cyclophosphamide in 25 patients. French Cooperative Study Group for Vasculitides. Br J Rheumatol 1997361290–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guillevin L, Cevallos R, Durand‐Gasselin B, Lhote F, Jarrousse B, Callard P. Treatment of glomerulonephritis in microscopic polyangiitis and Churg‐Strauss syndrome. Indications of plasma exchanges, meta‐analysis of 2 randomized studies on 140 patients, 32 with glomerulonephritis. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 1997148198–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tatsis E, Schnabel A, Gross W L. Interferon‐alpha treatment of four patients with the Churg‐Strauss syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1998129370–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danieli M G, Cappelli M, Malcangi G, Logullo F, Salvi A, Danieli G. Long term effectiveness of intravenous immunoglobulin in Churg‐Strauss syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2004631649–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keogh K A, Wylam M E, Stone J H, Specks U. Induction of remission by B lymphocyte depletion in eleven patients with refractory antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody‐associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum 200552262–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiota Y, Matsumoto H, Kanehisa Y, Tanaka M, Kanazawa K, Hiyama J.et al Serum interleukin‐5 levels in a case with allergic granulomatous angiitis. Intern Med 199736709–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiene M, Csernok E, Muller A, Metzler C, Trabandt A, Gross W L. Elevated interleukin‐4 and interleukin‐13 production by T cell lines from patients with Churg‐Strauss syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 200144469–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takemura S, Klimiuk P A, Braun A, Goronzy J J, Weyand C M. T cell activation in rheumatoid synovium is B cell dependent. J Immunol 20011674710–4718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong F S, Wen L, Tang M, Ramanathan M, Visintin I, Daugherty J.et al Investigation of the role of B‐cells in type 1 diabetes in the NOD mouse. Diabetes 2004532581–2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]