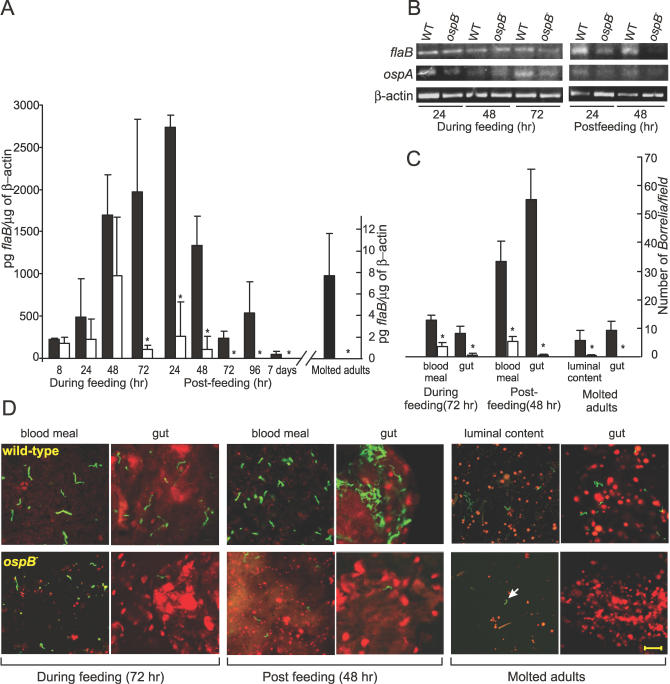

Figure 3. Influence of OspB-Deficiency on the Ability of B. burgdorferi to Survive and Colonize in Ticks.

(A) Results from the experiments with the ticks inoculated by feeding on infected mice are shown. The spirochete burden in nymphal and subsequently molted adult ticks is quantified by Q-RT-PCR. Value on Y-axis corresponds to pg of flaB/μg of tick β-actin in each cDNA sample. * indicates significant reduction (p < 0.05, Student t test) of the ospB mutant in ticks in comparison to the wild-type.

(B) RT-PCR analysis of the RNA samples extracted from nymphs is shown. RT-PCR of flaB and ospA transcripts were used to determine the presence of spirochetes; tick β-actin was used as an internal control for RT-PCR.

(C) Shown is the quantitative assessment of the number of spirochetes from 15 random microscopic field observations. Value on Y-axis corresponds to the number of spirochetes/microscopic field. Black and white bars in (A and C) indicate values for the wild-type and the ospB mutant spirochetes, respectively. Error bars define standard deviation (+) from the average value (mean).

(D) Shown are the representative confocal images of the I. scapularis nymphal ticks (fed on mice infected with the wild-type or the ospB mutant B. burgdorferi at the indicated time points) and molted adult ticks. Tick blood meal (in nymphs) and luminal content (in adult ticks) and gut tissues were stained for B. burgdorferi with FITC-labeled anti-Borrelia antibody (green) and for tick cell nucleic acid with propidium iodide (red). Arrow shown in the luminal content sample of the molted adult tick indicates the only ospB mutant spirochete seen in 15 random microscopic fields. Scale 20 μm.